The North Cascades Smokejumper Base, at its present location outside Winthrop in Okanogan County's Methow Valley, dates officially to 1945, when it became the fifth smokejumping base officially established by the U.S. Forest Service to fight forest fires from the air. The Methow Valley in North Central Washington served as the original testing site for the smokejumping program, dating to 1936 when the Forest Service began new experiments in combating forest fires from the air. Since 1945, the base has consistently served as one of seven smokejumper bases operated by the Forest Service for airborne firefighting across the Western states.

New Ways to Fight Fires from the Air

The use of aircraft to combat forest fires in the United States dates to 1919, when civilian pilots conducted air patrols both for fire detection and to observe fires as they burned in areas over California, Oregon, and the Northern Rocky Mountains. These flights were done primarily under contract, since the U.S. Forest Service did not then own planes or have trained pilots.

As the federal agency responsible for wildfire crisis response and resource management, the Forest Service next used water and chemical bombs to fight fires from the air in 1935 with the Aerial Fire Control Experimental Project. This was headed by David Goodwin, a Forest Service manager often credited as the father of smokejumping.

By 1936, the Forest Service had begun various operations involving the construction of remote airfields in national forests to serve as staging areas for firefighting supplies and equipment. Yet even this was a challenge for the crews who fought fires on the ground, since it still required them to pack these supplies overland on pack mules or horses, or by foot using backpacks.

While the airfields were being developed as one approach, other strategies using aircraft for direct deliveries were explored as well. The potential time savings in getting these materials to aid in firefighting led to new efforts to develop air drops of supplies by parachute, thereby bypassing the need for lengthy overland trips to the burn sites. This greatly enhanced the ability of the service to quickly deliver heavy loads of gear to ground crews -- "smoke chasers" -- in isolated areas where the terrain was difficult (Poyner III).

This method of cargo delivery was highly successful and became a standard in U.S. Forest Service firefighting. By 1936, the practice was perfected in the Pacific Northwest with everything "from axe-handles to eggs and wash pans and radios put down with negligible loss or breakage" (Hessel, 2).

"Smokejumpers"

Delivery of firefighters themselves by aircraft as a rapid response force to curtail a wildfire before it could grow in strength was a logical next step, and one the Forest Service soon looked to develop. The rapid delivery helped reduce and contain the damage caused by backcountry fires in remote areas, which translated into savings of resources, including manpower and materials expended to fight these fires.

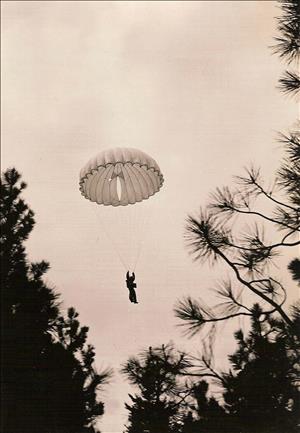

By the fall of 1939, the era of the smokejumper had begun. Several test dummies, each one the approximate weight of an average man with equipment, were dropped; these were followed by professional parachutists equipped with special padded suits, masks, and helmets. The final test group of five men included Forest Service staff who made a series of experimental jumps, among them Walt Anderson, who was the first to coin the term "smokejumpers" for those who were involved (Briscoe, 30).

The testing site was in a region notoriously prone to wildfires that afforded the Forest Service a good location from which to organize and train its new airborne firefighting force. This was the Methow Valley, near Winthrop, in the Okanogan (then Chelan) National Forest. The tests resulted in 58 total jumps successfully completed over six weeks. Two of the firefighters had never worn a parachute before (Anderson was one of them). The landing sites included meadows, slopes of mountainsides, and stands of forest timber.

Francis Lufkin, a Forest Service fire guard and lookout assigned to the Eight Mile Guard Station outside Winthrop, was another who participated in the testing program, first as a spotter for jumpers who got hung up in trees by their chutes, then as a smokejumper. He recalled his jump experience in a 1970 interview:

"I can't say that I was scared. I figured I could figure things out for myself ... I knew how the equipment worked, and I'd looked it all over. It was a real opportunity, as far as I could tell, to get in on something new. The ceiling was down very low that day, and I actually jumped into the clouds" (Doig).

Daren Belsby, in 2019 the Base Manager for the North Cascades Smokejumper Base, called the 1939 experimental jumps "one of the most influential events" in the long history of the Region Six smokejumpers in Winthrop (Belsby interview).

New Program in Two Regions

In his review of field reports, Forest Service manager David Goodwin wrote on January 16, 1940, that the results were favorable enough to recommend establishment of smokejumper units in two Western regions -- Region Six, covering Washington and Oregon, based in Winthrop, and Region One, covering Montana and Northern Idaho, based at Seeley Lake, Montana -- to serve as a rapid-reaction firefighting forces delivered from the air. These two regional commands would coordinate training, staff, and aircraft, starting with a new training program in Region Six that same year. Funding for the aerial fire-control program was approved in the spring of 1940. According to author and former smokejumper Fred Cooper, these "all service funds" for the new program were reserved in Washington, D.C., "to be used specifically for smokejumper operations" (Cooper email, January 31, 2019).

Resources for the two operational regions were shared. Johnson Air Service, operated by Dick Johnson and based in Missoula, was contracted by the Forest Service to provide service for all smokejumping operations in Region One and Region Six between 1940 and 1944. For cargo drops supplying firefighters on the ground, other aircraft were contracted to fly out of cities around Winthrop, such as Wenatchee.

The Region One program for smokejumpers in 1940 received nearly 100 applicants for review and testing at the Seeley Lake Ranger Station, sixty miles northeast of Missoula. Out of that group, just six men were selected, most of whom had extensive service histories as guards far back in the roadless areas of the northern Rocky Mountain national forests. The following year, the program would have 25 total smokejumpers for both Region One and Region Six.

It was not long after the initial training in 1940 that the smokejumpers of both regions saw action. Two smokejumpers from Region One -- Earl Cooley (1911-2009) and Rufus "Rufe" Robinson -- made the Forest Service's first-ever parachute jump to fight a forest fire on July 12, 1940, in the Nez Perce National Forest in Idaho. A month later, two members of the six-man smokejumper team for Region Six, Francis Lufkin and Glenn Smith, made the first jump in Washington to contain a wildfire on August 10, 1940.

Earl Cooley, a member of the original Region One smokejumper team from 1940, recalled the effort and caliber of person it took: "The first year that we worked, we had really tough guys, and they had to be in order to stay in the outfit" (Smokejumpers: Firefighters from the Sky).

The use of smokejumpers to fight fires resulted in substantial cost savings. For the 1940 fire season, where smokejumpers were used the average cost, including initial attack and follow-up expenses, was just $247 per fire. Without the jumpers, the cost per fire soared to an estimated average cost of $3,500 per fire. Even more importantly, the value of resources not burned was the direct result of the smokejumpers' effectiveness.

Smokejumper Program During the War Years

While it had proved to be a good location to train and stage smokejumpers, the Methow Valley outside Winthrop was still not recognized as an official smokejumper base. Training of new recruits for the program -- 100 candidates for the summer season of 1941 -- was shifted entirely to Seeley Lake in the Lolo National Forest in Montana. That year saw six more forest fires where smokejumpers from Region One in Missoula made a total of 34 jumps to stop fires in Montana and Idaho, while smokejumpers out of Winthrop fought three other fires in Washington.

The potential smokejumpers had to be single males between the ages of 21 and 25, in good physical shape, with firefighting experience. After a rigorous 10-day training program, 25 smokejumpers were graduated into service. The pay was $193 per month, with eight smokejumpers forming a rapid initial-attack force to fight forest fires in each of three regions -- the previously established Region One and Region Six, and a newly added Region Four covering Colorado, Utah, Western Wyoming, and southern Idaho.

With the advent of parachuting firefighters arriving by air came innovations in equipment and the outfits worn by smokejumpers. An article from 1941 described how these were designed to safeguard against injuries during a jump, while equipping every smokejumper to function as a one-man fire brigade capable of putting out fires at the source:

"Each man was provided with a two-piece padded suit consisting of a pair of high-waisted, low-crotched trousers and a high-collared jacket fitting inside the trousers so as to prevent up-thrusting snags or limbs from entering the suit. Straps on the legs of the trousers fitted under the feet so as to distribute part of the opening shock to the jumper's legs. Jumpers wear a football helmet and a steel wire mask as protection to head and face" (Hessel, 3).

Equipment for each smokejumper also included a 200-foot coil of rope he could use to lower himself to the ground in the event of a tree landing; orange streamers to signal to aircraft above; a two-way battery-powered radio; leather gloves; a knife for cutting away tangled parachute lines; and two parachutes (a 30-foot backpack canopy made by the Eagle Company and a 27-foot chest-pack canopy as a back-up). Firefighting tools and supplies were dropped separately to a jumper after he safely landed.

The program's renewed focus on Montana was partly the result of Forest Service funding for the program being limited following U.S. entry into World War II in December 1941. The single aircraft that had served as the 1939 testing aircraft was sold to reduce the continued cost of the program. The program also suffered by losing most of its veteran smokejumpers when they volunteered for active military service. Only five qualified jumpers returned in the summer of 1942; also, parachutes were diverted to the war effort.

As the war demanded more men, beginning in 1943, many new smokejumper candidates were Civilian Public Service men who were conscientious objectors to the war. Out of 300 volunteers, 60 were selected for training. They were trained at Seeley Lake and served as the Forest Service's smokejumping core through 1944.

Cooper described the typical training regimen for the new recruits:

"The training consisted of oral instruction and demonstration jumps by the professional jumpers trained earlier in the month at Winthrop while Frank Derry, the Instructor-Rigger, explained maneuvers. Next, demonstrations and practice let-down techniques were taught. Then, each new jumper made three jumps at Blanchard Flats, adjacent to an airstrip north of Seeley Lake, Montana. This was followed by each jumper making two or three nearby timber jumps, spotting themselves, going through let-down procedures, and retrieving their parachutes from trees" (Cooper, "Chapter 12," p. 3).

In 1945, the Region One and Region Six smokejumpers were supplemented by 300 African American paratroopers from the army's 555th Infantry Battalion, also known as the "triple-nickels" (Smokejumpers: Firefighters from the Sky). These troops had been assigned to the Pacific Northwest to thwart the threat of fires caused by Japanese incendiary balloons set adrift across the Pacific. In the last year of the war, the group made 1,200 jumps and helped extinguish 36 forest fires in the Pacific Northwest.

North Cascades Smokejumper Base

In 1945, the Forest Service officially declared a 19-acre site on Forest Service land adjacent to the Methow Valley State Airport (formerly Intercity Airport) the official site for the North Cascades Smokejumper Base. The location, which served as a training facility for existing and new smokejumpers in the Region Six group, eventually featured facilities including a parachute loft, a saw-maintenance building, an administrative building, a bunkhouse (added in 1950), and a jump tower with cables for practice jumps (rebuilt as a three-cable jump tower in 1974).

Francis Lufkin, who had continued to be a trainer, spotter, and smokejumper during the war, was the first manager for the new smokejumper base. Each summer the base staff led by Lufkin was responsible for training up to three dozen new recruits to parachute into Washington's forests to fight fires. Veteran smokejumper George Honey served as Lufkin's base assistant. In 1947, the base turned out 19 new smokejumpers in its first graduating class. The smokejumper crew at Winthrop that same year, numbered 15. Three of them were former military parachutists and the rest had been trained by the Forest Service.

High Standards as a Firefighting Resource

Over the next seven decades, the smokejumpers of the North Cascades Smokejumper Base set a high bar in the Forest Service and as a firefighting force for their Region Six area of responsibility.

The training regime in 1949 involved extensive physical-fitness preparation, designed to strengthen bodies against the stress of aircraft jumps and for fighting fires once on the ground. At the North Cascades base, this included a training area equipped with body-building aids, such as an eight-foot scaling wall, overhead ladder, and sets of horizontal bars for doing body bends at the waist. Smokejumper bases for other regions patterned their training after the base in Winthrop. In 1954, the North Cascades crew expanded to 32 smokejumpers.

A smoke chaser from the early 1960s recalled the jumpers' effectiveness when working in tandem with ground crews to fight fires:

"l worked for 2 summers, 1960 and 1961, for the Suiattle district U.S. Forest Service, as a 'smoke chaser,' not a jumper, we went in on foot or horseback to relieve the jumpers and mop up. Sometimes after many lightning strikes we were sent in on our own to mop up a strike site -- they would either fly us in on a helicopter or give us a set of co-ordinates and a map and a look-out would identify the site to deal with[.] I met many of the jumpers out of Winthrop, and collected a few parachutes and paper sleeping bags that they would drop into us, usually a team of 2 or 3 guys" (Poyner III).

During the 1965 fire season, the base force of 32 jumpers made 450 jumps to successfully fight 160 fires. The following year, the core of personnel was unchanged with 21 experienced jumpers and 11 rookie trainees. The response time for this force was remarkable, especially when an airplane was available to follow behind a lightning storm. In such cases, The Seattle Times reported, "the jumpers often reach a fire within five minutes of a [lightning] strike. Generally, it takes 30 minutes from the time a fire is reported until the jumpers are on the scene, depending on the distance from the field" ("Training 'Smoke Jumpers' ...").

Smokejumpers out of Winthrop mark key fire seasons that stand out in their years as a service. In the 1970 summer fire season, at that time one of the worst years on record in the state for forest fires, the smokejumpers from the North Cascades base made a total of 1,066 jumps to combat 223 forest fires. The fires occurred in two "bursts" that summer: one in July and another in August and September, with an overlap (Moody email). This has remained the record for the most smokejumps in one season, among the nine total smokejumping bases operating as of 2019.

In 1981, the North Cascades Smokejumper Base was reduced to just 11 smokejumpers, in a Forest Service effort to centralize operations for Region Six. The base became a "satellite" base, while Redmond, Oregon, served as the "core" base with 60 smokejumpers assigned there. Between 1983 and 1990, the number of smokejumpers in Region Six was established at 55, with 35 of these in Redmond and the remaining 20 in Winthrop.

Still a Dangerous Area

More than 70 years after the first success of the Winthrop smokejumpers, the Little Bridge Creek area in the Okanogan National Forest, just 10 miles west of the North Cascades Smokejumper Base, remained a fire-prone region. In August 2014, three major wildfires burned some 8,100 acres in the Chewuch drainage there.

Four years later wildfires again burned in the area, as the Crescent Mountain Fire crossed Eagle Creek on August 21, 2018. A Level 3 evacuation was issued for all persons living west of the Little Bridge Creek intersection in the Twisp River valley.

New Challenges

In the spring of 2017, the Forest Service conducted a cost-benefit study of the base in Winthrop to assess whether it should be relocated to another site, possibly in Yakima or Wenatchee. The study came under fire from local citizens and civic leaders, who objected to not being informed or included in public commentary about the potential closure of the base. The study also noted that three buildings at the base were located in the Methow Valley State Airport "obstacle-free zone" defined in Federal Aviation Administration regulations (McCreary). However, in the end the base remained in its original location.

While the fundamental purpose of the smokejumper program has remained largely unchanged over the years, the evolution of equipment, training, and techniques has enhanced operations at the North Cascades Smokejumper Base and the other smokejumper bases managed by the Forest Service. One such change affected a major piece of the smokejumper's equipment, the parachute -- according to North Cascades base manager Belsby, "the transition from a round to a square parachute system is the biggest challenge since 1939" (Belsby interview).

For the 2018 fire season, from June 21 through September 7, smokejumpers from the North Cascades Smokejumper Base made a total of 149 fire jumps to battle 29 fires.

Today the smokejumper program relies on the combined resources of both the Forest Service, part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), part of the Department of the Interior. Under the Forest Service, the North Cascades Smokejumper Base continues to serve as one of seven primary bases for approximately 320 smokejumpers stationed in Winthrop, Washington; Redmond, Oregon; Redding, California; McCall and Grangeville, Idaho; and West Yellowstone and Missoula, Montana. The BLM operates another two smokejumper bases out of Boise, Idaho, and Fairbanks, Alaska.