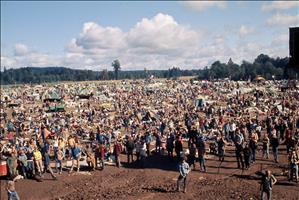

The Satsop River Fair and Tin Cup Races started its troubled four-day run on Friday, September 3, 1971, as the first "legal" outdoor rock festival in Washington after passage of a state law regulating such events. Organizers had to sue Grays Harbor County to get a permit, and the delay contributed to the festival's difficulties. But far larger factors were also at play. Times had changed in the few years since the huge and largely peaceful rock festivals first seen in 1968 and epitomized by 1969's Woodstock. Later gatherings increasingly were haunted by harder drugs, too much alcohol, and large numbers of participants who were at best indifferent to the counterculture's fading ethos of peace, love, and understanding. Despite manifold problems -- awful weather, bad drugs, counterfeit tickets, some violence, disappearing money, and no-show musicians -- the Satsop River Fair still managed to put on some good music, avoided major mishaps, and is fondly remembered by many as the last of its kind.

Born in the Northwest

The Northwest's seminal outdoor rock festival at a rural site was the legendary Piano Drop, a one-day fundraiser for Seattle's Helix newspaper and KRAB radio. On April 28, 1968, more than 3,000 people gathered near Duvall on the property of jug-band musician Larry Van Over, drawn by the irresistible lure of an upright piano plummeting to earth from a helicopter, with music provided by the Bay Area's Country Joe and the Fish and several local bands.

Four months later, the folks who organized the Piano Drop staged the first Sky River Rock Festival and Lighter Than Air Fair over the three-day Labor Day weekend. Thirteen thousand who paid to get in and several thousand who didn't camped on an organic-raspberry farm near Sultan in Snohomish County to listen to an impressive lineup of well-known musicians including, on the final day and unscheduled, the Grateful Dead. Sky River I, as it came to be known, is often credited as the first of its kind, anywhere -- an outdoor, multiday rock festival held at a rural site temporarily adapted to the purpose.

America's collective psyche was being pummeled in 1968, first by the Tet offensive in Vietnam, followed by the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy. There were massive anti-war protests throughout the country, and just days before Sky River I began on August 30, attacks by club-wielding police on demonstrators at the Democratic Party's national convention in Chicago were broadcast across the world. A nasty and violent mood was loose in the land, but Sky River I rose above it. Author Tom Robbins (1932-2025), who hosted the radio show "Notes From the Underground" on KRAB, was there, and he later recalled, "I never saw a frown. Everyone was happy and smiling. It was such a utopian event. There was a feeling of freedom and sharing and loving" ("Reviving the Spirit ...").

A little less than a year later, in August 1969, came Woodstock, the legendary gathering of more than 500,000 on Max Yasgur's 600-acre dairy farm in rural Bethel, New York. Just two weeks after that, on August 30, Sky River II kicked off at the Rainier Hereford Ranch near Tenino south of Olympia, organized by most of the same people as its predecessor. Despite the protests of the Tenino Chamber of Commerce and nearby property owners, an estimated 25,000 showed up that Labor Day weekend for another largely peaceful, joyous affair.

The End of Innocence

Then, on December 6, 1969, came Altamont, a free Rolling Stones concert cobbled together on short notice at a racetrack east of San Francisco. It was a disaster. Jefferson Airplane vocalist Marty Balin (1940-2018) was knocked unconscious on stage by a member of the Hell's Angels, the motorcycle gang entrusted with the event's security. Later, while Mick Jagger (b. 1943) was singing "Under My Thumb," a young man, Meredith Hunter (1951-1969), very high on speed, pulled a gun near the stage after being clubbed by Hell's Angels and was stabbed to death.

The violence of Altamont was symptomatic of the accelerating deterioration of the happy, hopeful, and brief counterculture zeitgeist that had reached its peak in 1967's "Summer of Love." Drugs were becoming more dangerous, and many and meaner people were drawn to rock festivals for reasons other than the ideals of peace, love, and fellowship.

In the summer of 1970, with a third Sky River in the works, communities throughout Western Washington mobilized to keep it away from their turf. Sky River III's promoters (an entirely different group from those who staged Sky River I and II) hoped to withhold its location until August 27, the day before the festival was to start, but their cover was blown. At a news conference on August 25 they announced that the festival site, near Washougal in Clark County, would accommodate 100,000 and could be quickly scaled up to handle 200,000. The event would run 11 days, from August 28 to September 7, promising a prolonged Bacchanal that confirmed the locals' worst fears.

Attempts to ban it began immediately, but young people were already pouring into the site. A Clark County judge issued a temporary restraining order, but authorities could not safely turn back the human tide, and the festival got underway more or less on schedule. Local police were overwhelmed, but Governor Dan Evans (1925-2024) turned down a request by Clark County commissioners to send in the state patrol or national guardsmen to break up the gathering, explaining that, "It would be asking for a lot of trouble" ("Sky River Fete Bogs Down ...").

Sky River III wasn't as peaceful as Sky River I and II, but it wasn't an Altamont-sized debacle, either. There were more heavy drugs, more (non-fatal) overdoses, one reported rape, a drowning, and a baby born onsite. The music didn't start until the third day, and the crowd (which never exceeded about 20,000) grew restive. But the festival somehow staggered through to the end, enduring a spell of terrible weather. Left in its wake were lawsuits and calls for legislation to prevent such events in the future.

The Festival Law

That would prove much easier said than done. After heated debates that featured considerable oratorical silliness about the threat hippies posed to civilization, the legislature responded in 1971 with a compromise act titled "Regulation of Outdoor Music Festivals" (1971 Wash. Laws). Its opening recitation was a litany of all the things that were considered bad about rock festivals:

"This invocation of the police power is prompted by and based upon prior experience with outdoor music festivals where the enforcement of the existing laws and regulations on dangerous and narcotic drugs, indecent exposure, intoxicating liquor, and sanitation has been rendered most difficult by the flagrant violations thereof by a large number of festival patrons" (1971 Wash. Laws).

Among much else, the statute sought to ensure that "proper sanitary, health, fire, safety, and police measures are provided and maintained" (1971 Wash. Laws). The requirements were detailed and burdensome, and violations punishable as gross misdemeanors.

One person deeply involved in getting the law passed was Gary Howard Friedman, an interesting character, to say the least, who was later described in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer as an admitted "ex-black marketeer, ex-convict, ex-narcotics agent, ex-computer operator and self-proclaimed promoter" ("The Wizard ..."). Despite no involvement in the earlier Sky River festivals, Friedman assumed the title of president of "Sky River Development IV" ("Festival Group Seeks ..."). He also touted himself as Governor Evans's consultant on rock festivals, a position that the governor's chief assistant, James Dolliver (1924-2004), later said never existed.

It was often impossible to sort the true from the untrue about Friedman, but no one denied that he played a significant role in fashioning rock-festival legislation that promoters could live with, if barely. When a Senate-approved version stalled in the House, Friedman, on May 8, 1971, threatened to run for a seat in the latter body. Coincidentally or not, the House passed the festival law later that same day, and it was signed by the governor on May 21, 1971. To the dismay of local authorities, Evans vetoed a section that would have permitted counties, cities, and other political subdivisions to enact their own regulations for outdoor music festivals, reserving to the state the sole power to do so.

The new law had one major real-world weakness -- authorities could impose whatever requirements they pleased on festival promoters, but when tens of thousands of young people showed up with partying on their minds, the rule book tended to go out the window. The reality was that "flagrant violations ... by a large number of festival patrons" (1971 Wash. Laws) simply could not be easily prevented, law or no law. The rock-festival statute made hard choices inevitable -- would attempts to strictly enforce its many requirements cause more trouble than any good that could come from it? The Satsop River Fair and Tin Cup Races put that conundrum to the test.

The Battle for a Permit

Friedman had a partner in his quest to put on a rock festival. This was Bill O'Neill, whose background was less varied and far less sketchy. The worst blot on O'Neill's record was an arrest for putting on a party for 500 people. He had a utopian vision of what a festival should be and would try to be a voice of relative reason when things soon started to go south at Satsop.

Friedman had raised some initial money by staging a few concerts, including fundraisers with volunteer bands at taverns that donated space for the shows. By the time O'Neill came on board there was enough cash on hand to start planning. On July 7, 1971, they announced that a lease had been signed for a site in Grays Harbor County, conditioned on the issuance of the necessary permit. The festival was named the Satsop River Fair and Tin Cup Races, and the site was the 77-acre Reality Farm on E Satsop Road. It was topographically ideal -- sloping land formed a natural amphitheater that led down to the Satsop River. The farm was owned in part by Max Hausher and Bob Plaja, who described it as a "community" comprising "16 people, 70 chickens, six ducks, and a pig" ("Satsop Bracing ..."). Reality Farm was paid $10,000 for the use of the land.

On July 9 Friedman and O'Neill met with Grays Harbor County officials and they all took a trip to the site. Friedman said that he believed the meeting had gone "very well" ("Rock Promoters Given Hearing ..."). It hadn't. Eighteen days later he was in court, asking for an order forcing the county commissioners to issue a permit, which they had refused to do.

Friedman began working the press and politicians. On August 5 he debated the issues with Grays Harbor County Prosecuting Attorney Edward Brown at a gathering of the County Commissioners Association in Union, Mason County. Friedman argued that "the counter-culture -- call it what you want, hippies, yippies or long-haired freaks" rejected "the system" as "hypocrisy, as a failure to live up to its own ideals." The answer, he preached, was for the disaffected to "get back into the system because that's where the power is." Denying the permit, he argued, would only further alienate the young ("Promoter Sees Rock ..."). As often with Friedman, his sincerity was difficult to judge.

On August 19, just two weeks before the festival was scheduled to start, King County Superior Court Judge Charles Z. Smith (1927-2016), sitting in his Seattle courtroom but in the capacity of a "visiting judge" for Grays Harbor County, heard from both sides. The promoters argued that the intent of the festival law was "to regulate, not prohibit" ("Judge OK's Plan ..."), and said they had substantially complied with all its requirements. The chasm separating the sides' respective views was illustrated (and the county's argument not greatly helped) by prosecutor Brown's claim that "youths could find comparable entertainment by taking their portable radios to county and state parks or the Seattle Center" ("Judge OK's Plan ..."). At the end, Judge Smith ordered the county to issue the permit, conditioned on the promoters posting by August 30 a $30,000 bond and proof of $50,000 in property insurance.

A Mad Scramble

Some preliminary work was underway at Reality Farm, but by the time the permit was granted on August 31, there was very little time and still lots to do. Money, at least at this early stage, was not a problem. A Portland woman, Janet Levin, had provided a $70,000 interest-free loan, and Herman Sarkowsky (1925-2014), a Seattle developer, gave Friedman a $60,000 unsecured but interest-bearing loan. Sarkowsky had been recommended to Friedman as a possible backer by Washington Secretary of State Lud Kramer (1932-2004). There may have been as much as $210,000 in start-up money, and Friedman later said that $60,000 of it came from him, a claim co-promoter Bill O'Neill rejected.

With just a few days remaining before the gates were to open, festival organizers flooded Reality Farm with (according to The Seattle Times) more than 800 workers. They erected a massive stage with a state-of-the-art, 500-watt sound system (which soon failed); built 95 concession stands; made space for two helipads -- one for entertainers, one for medical evacuations; planted a forest of utility poles to carry power from a huge diesel generator to the stage and outdoor lighting; ran water lines; helped place 104 Sanikans; and created a fenced-off area as a campground and parking area for motorcycle-club members. Much of the work was done in pouring rain, leading O'Neill to ask, "Why is the weather treating us this way?" ("Satsopping Wet").

Things Fall Apart

Ironically, the county's delay in granting a permit created some of the very problems it had cited as reasons to ban the festival altogether. Even two undercover Washington State Patrol officers who lived for five days in a camper on the site, posing as concession workers, thought so. In their post-festival report, troopers J. D. Young and D. G. Stathas, noting the deteriorating "health standards," wrote, "We feel that if the promoters had at least two weeks to prepare the site and better governmental control most of these problems could have been eliminated" ("Inter-Office Communication"). But no amount of preparation time would have done much to prevent many of the festival's other problems, which had more do with an unfortunate mix of bad weather, bad choices, bad drugs, and bad behavior.

First, the weather. It didn't rain all the time, but it rained for days before the festival began and frequently during its first two days. Most of Reality Farm became a churned-up quagmire, and a stiff, chill wind often swept the site. The mud made for slippery walking, dampened the mood, and also hid sharp objects -- mostly broken glass. The Open Door medical clinic on the site spent nearly as much time patching up cut feet as talking down bad trips. On Saturday a bus ferrying people between the site and parking lots up to 10 miles distant slid off a 30-foot cliff, injuring eight people seriously enough to require hospitalization, one by airlift.

Poor choices were legion, and included gulping down mind-altering substances bought from strangers, consuming unhealthy amounts of alcohol, and picking fights with the wrong people. Much but not all of the bad behavior at Satsop could be attributed to the combination of drugs and alcohol, mainly the cheaper varieties of wine, with gallons of Cribari being favorites. Pot smokers caused little if any trouble, and even those who overindulged on psychedelics -- LSD, mescaline, MDA, psylocybin mushrooms, and a pharmacopeia of other reality-warping things -- usually got by with a little help from their friends, or from the folks at the Open Door Clinic. But on Sunday, September 5, two young people made a really bad choice by getting into a confrontation with two bikers. They were shot for their trouble, and although their wounds were not serious, ambulances were entering and leaving Reality Farm with worrying frequency.

There was one drug that was particularly problematic, especially when combined with alcohol. It was a manufactured pharmaceutical and relative newcomer to the festival scene, and it probably caused more trouble than any other single substance. It was Seconal, a powerful barbiturate that much later became accepted for use to voluntarily end one's life under Washington's Death With Dignity law. In 1971 it was manufactured by Eli Lilly & Company and sold in red capsules.

When Seconals first hit the streets, they were for obvious reasons called "reds." Before long they had earned the name "stumblers," an accurate description of the drug's effect on one's ability to walk. Alcohol made things considerably worse. At Satsop, people high on wine and Seconal wandered about in a near zombie-like state, stumbling into strangers' tents, into campfires, into ditches, stumbling into anything that got in their way.

And then there was the watermelon truck. On September 5, a truck nearly overflowing with watermelons was making its way slowly through the mud, and a few folks decided that the melons belonged to the people and should be liberated. This spirit of sharing was seen by the driver as theft -- he hit the gas to escape and ran over several campers who were in the way. Had the ground been dry it could have been disastrous, but the mud provided a cushion, and the worst injuries were two broken ankles. But the image of a truck full of watermelons running amuck through a mob of sodden hippies became emblematic of the Satsop River Fair, rarely left unmentioned in later accounts.

A little more than half the major advertised bands and performers would eventually appear and play; others were at a motel in Olympia, about 35 miles distant, but came no closer. As the festival descended into confusion and financial disarray some, notably Ike & Tina Turner, Derek & The Dominos (with Eric Clapton), Quicksilver Messenger Service, War, Earth Wind and Fire, Leo Kottke, the Everly Brothers, and Captain Beefheart, either demanded payment in advance or found other reasons to not show up.

Even so, and despite problems with the sound system, some great music was heard -- Delaney and Bonnie, John Hammond Jr., Wishbone Ash, Eric Burden, Jimmy Witherspoon, Charles Lloyd, Spencer Davis and Peter Jameson, Albert Collins, Steve Miller, the Youngbloods, and others. A few of the acts played more than one set to help make up for the no-shows. On occasion, people from the crowd would take to the stage and perform, enthusiastically if not always well.

Where's the Money?

The Satsop River Fair became more shambolic each day, with something new going wrong seemingly every hour. Late Saturday, only its second day, it ran out of money. The firm that provided 40 security staff (including several impressively large men on horseback) was threatening to leave. Clean-up crews, electricians, ticket takers -- in fact almost everyone who had been promised pay for work -- were threatening to bail out. Even the helicopter pilots who flew in performers and flew out medical emergencies had just about had it.

Perhaps most ominous, the man who owned the sound system warned that he would pack up his equipment and leave by 9 p.m. Saturday if he wasn't paid. At an emergency meeting shortly before that deadline, Ed Goehring, nominally the festival's head of security, said, "If the sound system is turned off tonight, then that's not a crowd out there anymore -- that's a mob" ("Dramatic Meeting ..."). There was talk of alerting law enforcement to the potential need for riot control.

Bill O'Neill, who had so far displayed remarkable sangfroid, was in panic mode: "It's like a run on Wall Street. Here we have all these thousands of people and yet we have no bread ... and the workers want their pay right now" ("Dramatic Meeting ..."). And even the relentlessly cheerful Edd Jeffords (1945-2002), a mild-mannered journalist who had the unenviable job of press liaison, had nothing optimistic to offer.

Although as many as 100,000 people (accounts varied widely) may have entered the site, "there was an immense gap between the size of the crowd and the income promoters reported from ticket sales" ("Dramatic Meeting ..."). Money, lots of it, had simply disappeared, either through rampant petty filching or in large chunks. The situation was made worse by a flood of counterfeit tickets. Fairly or not, Friedman, who had disappeared for a couple of days (supposedly tracking down the counterfeiters), was assigned much of the blame. He sat in uncharacteristic silence at the meeting as one by one the others in the room told him they would no longer take directions from him.

The remaining people in charge were left contemplating the abyss. Then, with time and options running out, Janet Levin, one of the original financial backers, pulled them back from the brink. Faced with a choice between letting the festival end prematurely and in chaos or providing more money, she generously chose the latter. Enough bills were paid to keep things going. The sun came out Sunday, the show went on, and the Satsop River Fair and Tin Cup Races cruised to an unexpectedly soft landing. Monday and Tuesday saw a muddy but quiet exodus from Reality Farm. Left behind were a jumble of abandoned campsites and garbage, a less-than-enthusiastic clean-up crew, and an estimated $150,000 financial loss.

Post Mortem

Bill O'Neill and Edd Jeffords came away from Satsop with their friendship and their reputations for integrity intact. They moved to Jeffords's home state of Arkansas and became active in the back-to-the-land movement there. In 1973 they were instrumental in organizing the Ozark Mountain Folk Fair, a music festival and craft fair on 120 acres of wooded hills near Eureka Springs over the Memorial Day weekend. Jeffords later attended law school at Baylor University, graduating in 1985, and became an assistant state attorney general in Texas.

It is unclear whether Herman Sarkowsky was repaid his $60,000 loan, but Janet Levin, whose generosity may have prevented disaster, was eventually fully reimbursed, according to her attorney. The owners of Reality Farm were not so lucky. Bob Plaja and his partners had received the $10,000 for the use of the property for the festival, but were left with substantial cleanup and road-repair expenses. They stopped making payments on the land in the spring of 1972 and it was ordered returned to the previous owner in August that year.

The mystery around Gary Friedman intensified in December 1971, when it was revealed that from March to the end of June that year, including while he was lobbying for passage of the festival law, he was being paid $150 a week to work as a "special operative" for the Drug Control Unit of the state patrol ("Rock Promoter Identified ..."). He would set up drug buys for an undercover officer, who would then arrest the sellers. Suspicion swirled around Friedman, including allegations that he was responsible for the counterfeiting of tickets to his own festival. Nothing was proven and he receded from view.