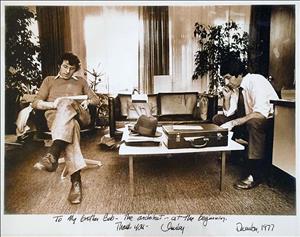

Bob Royer was one of Seattle's deputy mayors from 1978 to 1983, working closely with his brother Charley Royer (b. 1939), who served three terms as the city's mayor from 1978 to 1990. Their mayoral arrangement became known as "Charleybob," yet despite inevitable complaints about nepotism, it seemed to work quite well. Bob was the more animated of the two, known for making colorful statements and writing colorful letters. He said his greatest personal achievement was negotiating the Skagit River Treaty with British Columbia in the early 1980s, relieving Seattle of a controversy that had lingered for more than 15 years.

Beginnings

Robert (Bob) Royer was born in Medford, Oregon, on September 16, 1943, to Russell Royer (1903-1967) and Mildred Hampson Royer (1900-1980). He had a brother, Charles (Charley), who was born in 1939. It was a blended family. Mildred had already raised one child -- her younger sister, Barbara (b. ca. 1921) -- by the time Charley and Bob were born, and took on a niece, Beverly (1935-?), after her brother's wife died. "I considered her a sister, not a cousin," Bob Royer said of Beverly in an interview with HistoryLink. "She was a very interesting woman ... she had her own talk show in high school in Medford in the 1950s, discussing politics from a Democrat's perspective. She raised a few eyebrows."

Bob soon found that he too had an interest in the media. After several moves around Oregon while he was a boy, the family settled in Oregon City by the time he was in high school. Royer landed a job his sophomore year at the local newspaper, the Enterprise-Courier, covering sports and an occasional school-board meeting. In 1961, he started college at the University of Oregon in Eugene. He considered a major in English literature, but instead chose history, not necessarily out of a strong interest in history; he was more interested in getting a degree. Before long he was working at the campus radio station, and in 1962 he began working part-time in the newsroom at KEZI-TV, the American Broadcasting Company (ABC) affiliate in Eugene.

After his second year of college ended in the spring of 1963, Royer took a year off and spent it in Europe. He was in Marseille, France, on November 22, 1963, the day President John F. Kennedy (1917-1963) was assassinated. The army had drafted Charley in 1961; he was stationed in Fort Hood, Texas. The brothers hadn't been close growing up, mainly because Charley was several years older, but that changed after the assassination. They began writing back and forth, first about Kennedy, then other topics. By the time Bob returned to Oregon in 1964, the two had become closer, and by the end of the year they were working together at KEZI in Eugene.

Bob continued to pursue new experiences. He joined the Peace Corps and traveled to Nigeria in early 1966 to help put together a television program that the Peace Corps had created to train teachers into becoming more proficient in teaching science. He had the misfortune to arrive just as a series of military coups began to rock the country, making it impossible for the program to continue. He returned to the United States, finished his degree at Portland State in 1967, and married Linda Gist (b. 1941) later that year.

Vietnam and Television

Bob and Linda Gist Royer moved to Seattle in 1968, where he produced documentaries for KING-TV. He covered Robert Kennedy's (1925-1968) presidential campaign as it swung through Oregon that spring just weeks before Kennedy was assassinated. And a problem he'd been grappling with for a while came to a head that year. The Vietnam War was three years old in 1968, and Royer had been bobbing and weaving with the draft board for a year or two, doing his best to avoid the draft. Now, with his deferments running out, he thought about going to Canada, and even visited the Canadian consulate to pick up the immigration forms. But when another draft notice arrived from the army in late 1968, he reported to Fort Lewis.

He spent a year in Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City) in 1969 and 1970, producing television programming for the troops from Saigon to Quang Tri in the north. He returned to his job at KING in the summer of 1970, again reporting and producing documentaries. Charley likewise arrived at KING in 1970 and worked as a news analyst. In 1973, Bob won a scholarship with the Kiplinger Foundation, a grant-making foundation in Washington, D.C., which allowed him to work in the office of Senator Warren Magnuson (1905-1989). He also snagged a job as a spotter for ABC News during the Watergate hearings that year, reporting back to ABC on what was happening and who was there. "That period of time really charged me up," he said. "I met some amazing people" (interview).

Royer returned to Seattle later in 1973. He and his wife Linda had had a daughter, Amy, in 1970, but the marriage ended in 1974. He meandered through the mid-1970s at KING, restless and looking for new ideas. He was considering a position at a television station in Minneapolis when, in 1976, Charley asked him to join his mayoral campaign.

Being Involved

"Charley had talked about running, but I never thought he would. He had a great job as a news analyst at KING 5," Royer said. "I was not planning on being involved" (interview). But involved is what he became, along with his mother Mildred and Charley's wife, Rosanne. Bob and Dick Kelley (a King County Democratic party official) managed Charley's campaign in 1977, with Bob focusing on media relations and fundraising. After a disorganized start, the campaign hit its stride by the summer of 1977.

"It [the campaign] turned out to be a lot easier than I ever thought. We positioned ourselves as different," Royer said. "We had 3,000 volunteers, and doorbelled not just to hand out literature, but so we could listen to people. Every night we polled our volunteers on the people they'd talked to and categorized them as 'saints, saveables, and sinners' to give us an idea of where we were. It turned out to be accurate" (interview). In a field of seven candidates, Charley Royer won a run-off spot in the primary election that September along with Paul Schell (1937-2014). "We were surprised. We thought we'd be running against Phyllis Lamphere," Bob said. (Lamphere [1922-2018] was a Seattle city council member and prominent civic leader.) Charley won outright in the general election that November, defeating Schell by a comfortable margin.

Bob then served as a deputy mayor for his brother for more than five years, from January 1978 until April 1983. He was joined by a second deputy mayor, Dick Kelley, from 1978 to mid-1979, when Kelley was replaced by Jack Collins, a friend of Charley's from his KEZI days in Eugene. Bob Royer handled policy matters, while Kelley and Collins handled administrative ones.

Charley's mayoral tenure got off to an inauspicious start. "We were a little full of ourselves at the beginning," Bob said. " ... We had a tough first year. We made our fair share of mistakes" (interview). The mayor's staff had little governmental experience, and Charley later admitted to making a few bad hires. Relations with the city council were tense, and Charley ticked off the Seattle police not long after his inauguration by proposing limits to police use of firearms, the first such action by a major city. The city council approved the limits in May 1978.

There were successes as well. In June 1978 the West Seattle Bridge was rammed by the freighter Chavez and locked in an open position, closing it to traffic from Seattle to West Seattle for six years. Charley Royer and city council member Jeanette Williams (1914-2008) worked with Senator Magnuson and Transportation Secretary Brock Adams (1927-2004) to obtain $60 million in federal funds for a new bridge, which opened in 1984. Royer also opened community health clinics around the city (a total of 20 by the time he left office in 1990), and focused on improving access to senior and multi-family public housing. "Housing and parking were issues in 1978 just like they are today [2019]," Bob Royer said. "Charley recognized Seattle needed more affordable housing before it was in vogue" (interview). With the mayor's backing, Seattle voters approved a $48 million bond to construct more senior housing in 1981, and a $49 million levy to build low-income housing and rental housing for special-needs residents in 1986.

Outspoken and Occasionally Outrageous

Meanwhile, Bob was appearing recurrently in the news, described variously as "outspoken, controversial, and occasionally outrageous" (Chesley). He was the yang to Charley's yin, more mercurial and blunt. Charley might not have always told you what he thought, but Bob would. He was an avid letter writer, scolding his critics with missives such as this to Seattle Weekly editor Rebecca Boren: "Dear Rebecca: Your stuff about mayoral activities is consistently vicious, bitchy and unfair and quite often uninformed. Other than that it's terrific stuff" ("It's a Letter ... "). Recognizing that he may have overreacted, he sent Boren a follow-up letter a week or so later, spoofing his earlier complaint. He wrote hundreds of letters to publishers, city-council members, constituents, even Senator Henry "Scoop" Jackson (1912-1983). Royer explained his philosophy to a Seattle Post-Intelligencer reporter in 1983: "It's better to be occasionally dumb and frank and occasionally angry than it is to be a blank" ("It's a Letter ... ").

His pronouncements weren't confined to paper. One of his more memorable moments came at the 1979 Washington Public Power Supply System board meeting when he commented that its budget could buy "three billion Tootsie Rolls or 300 pounds of marijuana" (Chesley). "It was a stupid mistake," Royer conceded when he was interviewed by HistoryLink, explaining he thought the budget was excessive. "They gave a presentation demonstrating how much their budget was ... one example they gave was how high dimes could be stacked to equal the amount. So I gave my own presentation" (interview). When he resigned as deputy mayor in 1983, Seattle Times columnist Don Hannula wrote, "What Bob Royer was best at was candor, whether it was a foot in someone else's mouth or his own" ("Debobbing ... "). There was no suggestion that he was a blank.

His sense of humor became a favorite for reporters. Not long after becoming deputy mayor, he received a questionnaire from a city newsletter profiling new employees. One question asked how he got his job. Royer replied, "I slept with the mayor in the '40s and '50s" ("Debobbing ... "). Later in his tenure, the city was criticized when it paid an uncover policeman taxpayer money to have sex with a prostitute in an attempt to entrap her. Royer dismissed the encounter as a "nearie" ("Debobbing ... "). One of his oft-quoted statements came in 1979, when Bella Abzug (1920-1998) visited Seattle. Abzug, a flamboyant former member of Congress from New York, liked to wear hats when hats weren't chic. Royer penned a limerick in her honor, which he recited when he introduced her at a banquet: "What rhymes with Abzug? A good question's that; She's always in this or that flapzug, wearing that goddamn hat" ("It's a Letter ... ").

'Charleybob'

Charley Royer was easily reelected in 1981, and won again in 1985, becoming the first mayor in Seattle history to win three four-year terms. The two brothers, and the Seattle mayorship, came to be known as "Charleybob." They took a lot of heat because of the nepotism concerns, but the arrangement worked. "I relied a lot on Bob and we worked very well together. I just felt I needed someone I could trust completely," Charley said in 2007 (Chesley). Bob often filled in for Charley when Charley was out of Seattle, and he frequently helped Charley write his speeches. The brothers became so well known in the city that in 1982 or 1983, the Seattle Weekly held a Norwegian-joke contest, promising a "Charleybobber" as a prize. The Charleybobber was a head clamp-on with two springy antennas topped with pictures of the Royer brothers, and it quickly became a collector's item.

In 1981 Bob Royer married Jennifer James (b. 1943), an author and psychologist who during the 1980s dispensed advice on KIRO-TV and radio as well as in The Seattle Times. In the spring of 1982, there was a city ethics probe in response to a complaint filed over a $600 contract awarded by the City Water Department to James to conduct a three-hour affirmative action seminar for department workers. There was no evidence that Royer had been involved in granting the contract or that he was even aware of it, and he was soon exonerated. He claimed afterward that the only thing he'd lost in the probe was his sense of humor.

The 'Pina Colada' Treaty

Less than a year later, Royer accomplished what he later described as his life's singular achievement when he helped negotiate an end to the High Ross Dam controversy. In 1967, Seattle City Light and the Canadian province of British Columbia signed an agreement that would have allowed the City of Seattle to raise Ross Dam, located in northern Whatcom County just south of the Canadian border, in order to generate more electricity for Seattle. However, while the dam was in Washington, Ross Lake, which formed behind it, stretched north into British Columbia, and raising the dam would have flooded B.C. lands further. Controversy over the agreement ensued north of the border, and the B.C. government balked at moving forward. The controversy stretched into 1983, when an agreement was reached in which City Light dropped plans to raise the dam in exchange for the right to purchase power from the province until 2065. A formal agreement, known as the Skagit River Treaty, was signed on April 2, 1984, and Royer represented the City of Seattle at the signing ceremony.

He'd taken a lead role in representing the city in the negotiations, after which he traveled to Maui for a little r&r. Relaxing at a resort, he saw B.C. Premier William (Bill) Bennett (1932-2015) sitting two tables over. Royer walked over and introduced himself, and to his surprise, Bennett invited him to join him. Bennett was drinking a pina colada, and offered Royer one. He was no pina colada fan, but he took the premier up on it. The two men talked at length about the agreement, and even came up with a whimsical nickname for it: The Pina Colada Treaty.

Thereupon

Shortly after the agreement was reached in early 1983, Royer announced he was stepping down as deputy mayor. Even his critics -- including The Seattle Times's editorial page -- acknowledged his accomplishments. In writing of his work on the Skagit River Treaty, the Times observed that "Deputy Mayor Bob Royer, who is leaving City Hall, will go out on a high note. In representing the city in the final negotiations, he showed the requisite toughness and understanding" ("Ross Dam Settlement"). Perhaps not surprisingly, Royer had no immediate plans when his resignation became effective that April. He went on to open his own public-affairs firm later in 1983 and ran it until 1999, representing clients as diverse as the Bonneville Power Administration and Rabanco Companies, a waste-collection and recycling company based in Seattle. He continued to do pro bono work for the mayor's office for a couple more years while slowly fading from the spotlight.

Royer served as Chair of the Washington State Centennial Commission in 1988 and 1989, and served on the board of the Washington Public Power Supply System (now Energy Northwest) in the 1990s. His marriage to Jennifer James ended in 1988, but in 1991 he married attorney Sidney Stillerman (b. ca. 1951), and became a father to her young children Ari (b. 1983) and Chloe (b. 1986). The marriage ended in 1997, but he remained close to the two children. He spent most of the 1990s running his own firm, operating under such names as Bob Royer Creative Services and Bob Royer Communications Inc. He briefly served as spokesman for beleaguered Mayor Paul Schell after Schell came under fire for what many saw as the city's botched response to the WTO protests in downtown Seattle in late 1999. In September 1999, Royer returned to city employment when he became Public Affairs and Communications Director for Seattle City Light.

The next decade brought more changes for Royer. While at City Light, he grappled with the Western Energy Crisis of 2000-2001. Largely forgotten after the subsequent terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the crisis flowed from corrupt energy traders manipulating prices on the energy market, driving prices sky-high and forcing City Light (and other utilities across the West) to scramble to pay for it. In 2006 he took a new job with Coastal Environmental Systems in Seattle, where he helped reengineer weather-system software to improve communication and emergency responses to the release of hazardous materials or chemical attacks in urban centers. In 2008 he joined Gallatin Public Affairs, a Seattle company. He worked there for more than 10 years, providing leadership and guidance on client work in areas such as energy, media, public utilities, crisis communications, and local government affairs. There were personal changes too. Royer married Barbara Larimer (b. 1958) in 2002, and they moved into Seattle's Belltown neighborhood in 2009.

He never lost his enthusiasm for writing or history. In 2011 he developed his own blog, the Cascadia Courier, and posted approximately 100 in-depth stories about a wide range of topics -- plenty of Seattle, but plenty of other topics as well, ranging from his family to food to the anniversary of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act to the murders of a CBS and NBC television news crew in Cambodia in 1970. He wrote for Crosscut, an independent online news site. He served on the board of HistoryLink for more than 10 years, and as board chair for a number of those years.

Early in 2018, Royer noticed a bump on his right arm. His doctor dismissed it as a cyst, but when the cyst failed to respond to antibiotics and grew to the size of a ping pong ball, doctors took a biopsy. In April 2018 he was diagnosed with Merkel cell carcinoma, a rare type of skin cancer that is especially aggressive. In less than a year, the cancer had forced him into retirement. He died on April 17, 2019.

In an interview with HistoryLink in March 2019, Royer was reflective and grateful for his years in media, politics, and public affairs. He spoke of the many friends he made with particular fondness. "I've been really lucky," he said. "Sometimes I think it's just because I answered the telephone."