Seattle has a tradition of being at the vanguard of technological innovation, a place where imaginative thinkers such as Bill Gates, Paul Allen, and Jeff Bezos transformed the world with ideas. One of the earliest of these celebrated talents was an adolescent named Alfred M. Hubbard, who made his first newspaper appearance in 1919 with the exciting announcement that he had created a perpetual-motion machine that harnessed energy from the Earth's atmosphere. He would soon publicly demonstrate this device by using it to power a boat on Seattle's Lake Union, though, at the time, heavy suspicions were cast about the legitimacy of his claims. From there, Hubbard would lead a storied life in which he assumed several roles: charlatan, bootlegger, radio pioneer, top-secret spy, uranium entrepreneur, and millionaire. In 1950, after discovering the transformative effects of a little-known hallucinogenic compound, Hubbard would become the "Johnny Appleseed of LSD," introducing the psychedelic to many of the era's important thinkers and transforming a generation. Famous California psychiatrist Oscar Janiger once said, "Nothing of substance has ever been written about Al Hubbard, and probably nothing ever should." And yet, there is little dispute regarding the fascinating scope of his adventurous life.

The Atmospheric Power Generator

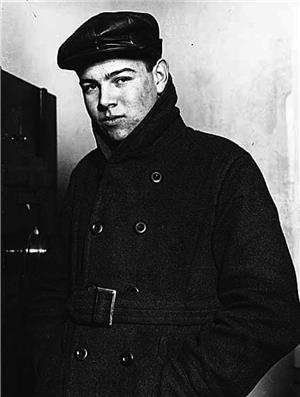

Alfred Matthew Hubbard (1901-1982) was born on July 24, 1901, in Hardinsburg, Kentucky. His parents, William and Nellie Hubbard, were unemployed, and the family lived a poverty-stricken existence until moving to Washington state to seek better job opportunities. Hubbard's father had two brothers living in the town of Northport, and he was able to support his family with various lumber and mining jobs throughout Eastern Washington. A young Hubbard once accompanied his father for a mining job in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, and found himself developing a fascination with the machinery being used at the mining camp. Around the same time, one of Hubbard's uncles introduced him to the field of metallurgy. As Hubbard would recall, these early experiences led him to develop a lifelong obsession with science and technology.

The Hubbards eventually relocated to the Hood Canal area, where Al attended school until dropping out in the eighth grade. When Hubbard was 17, his father accepted a job at the Skinner & Eddy shipyard in Seattle. It was during this period that Hubbard began entertaining his dream of becoming a man of science. Drawing direct inspiration from inventor Nikola Tesla (1856-1943), Hubbard began splitting his time between Everett and Seattle while working on a device he would name the "atmospheric power generator." According to Hubbard's claims at the time, his device was a fuelless engine that drew energy from the Earth's atmosphere.

On December 17, 1919, the front page of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer featured a photograph of Hubbard demonstrating his contraption by using it to power a lightbulb. A few days later, a local newspaper ran the headline that Hubbard had made a discovery which "promises to revolutionize the world!" ("Editorial Paragraphs ..."). He claimed that his motor could be used to power cars, boats, and planes, using nothing more than electricity derived from the air. Naturally, this attracted the attention of scientists, many of whom were interested in examining this exciting new device. Hubbard declined these requests, stating that he needed to protectively safeguard his invention until it had received a patent. His one exception was Rev. William E. Smith, a professor of physics at Seattle College (later Seattle University). Hubbard reasoned that a science professor, who was also a devout religious man, would be an especially credible source and approached Rev. Smith about inspecting his device and giving a testimonial about it to the local press. Upon examining the device, Smith testified that the contrivance would "advance the whole theory and practice of electricity beyond the dreams of scientists" ("Professor Permitted ...").

Decades later, Smith would offer a much different account, stating that the device was an obvious fraud and that Hubbard was a bunco man seeking wealthy bankers to endow him with cash. Hubbard didn't do much to quash such rumors when he founded the Hubbard Universal Generator Company. With this new start-up business, Hubbard began seeking donations from local investors with the promise that millions of dollars in dividends would be paid back once the device enjoyed commercial success.

On July 28, 1920, Hubbard held a public demonstration of his device by using it to power a boat on Lake Union. At the specified time, a crowd gathered at the Queen City Yacht Club on Portage Bay to witness this historic event. Many potential investors, curious about the veracity of his claims, were in attendance. Waving to the crowd from a nearby wharf, Hubbard powered up his device and launched the 18-foot boat out into the water. Joining him onboard was his father, as well as an investor whom he agreed could accompany them. The demonstration got off to a shaky start when Hubbard had difficulty getting the motor started and had to make frequent stops to prevent the generator from overheating. The boat was eventually able to attain speeds up to 10 knots and was out on the lake for more than an hour. Local newspapers heralded the event as a scientific breakthrough, though several local capitalists were left skeptical about what was actually powering the generator, including the investor who'd been onboard. An engineer in attendance summarized his impression by declaring to a reporter, "Attempted perpetual motion. All bosh! Another Keeley motor. He’s a faker!" ("Boy Inventor Drive ...")

A few months after the Lake Union event, it was reported that Hubbard had used his generator to power an automobile in Everett, attaining speeds up to 22 mph. In November of that year, Hubbard married his first wife in the town of Snohomish and was reportedly working on an X-ray machine that used magnetic waves to take photographs of the human anatomy. Other accounts alleged Hubbard had invented a device that restored sight to blind people, and rumors began circulating that local aviation companies were interested in obtaining the rights to his generator.

Despite the positive local publicity, Hubbard made a sudden move in 1921 to Pittsburgh, where he began working for the Radium Chemical Company. It was rumored that his hasty departure from Seattle was prompted by angry investors demanding their promised returns. Radium Chemical Company had agreed to fund the completion of Hubbard's power generator in exchange for a majority stake of the device. After only a couple of years, though, the two parties severed ties and there is no record that Hubbard ever developed any type of technology for the company. Several years later, he finally admitted to the Seattle Post Intelligencer that his power generator did not draw electricity from the air; rather, it extracted energy from a substance known as radium, and that his original claims were merely subterfuge to protect his patent rights. After this, no further mention of the atmospheric power generator appeared in the public record, though in 1924 Hubbard filed a patent (U.S. Patent 1,723,422) for an Internal Combustion Engine Spark Plug, which used an electrode doped with Polonium, a radioactive isotope. This patent was granted to him in 1929.

Bootlegging and the Birth of Seattle Radio

In 1923, Hubbard had returned to Seattle from Pittsburgh with a new interest in the growing field of radio technology. He and his wife rented a tiny apartment in the University District neighborhood and Hubbard opened a radio supply store near the Colman Dock in downtown Seattle. Soon after the opening of his business, Hubbard was paid a visit by a well-dressed gentleman who introduced himself as Roy Olmstead. Hubbard immediately recognized him, as he was known throughout the city as the "King of the Bootleggers." This was during Prohibition and Olmstead, who was running the area's largest liquor smuggling operation, had begun entertaining the idea of a legitimate business to fall back on. Olmstead (1886-1966) was undoubtedly aware of Hubbard's reputation as an inventor, and so approached him about building a radio station.

Recognizing a good financial opportunity when he saw one, Hubbard agreed to build a station for Olmstead in exchange for having all of his debts being settled, as well as the promise of a regular paycheck. Olmstead agreed to the deal and even moved the young couple into the basement of his palatial estate in Seattle's Mount Baker neighborhood. In no time, Hubbard and his wife were enjoying the luxury of living at Olmstead's mansion. Hubbard transformed Olmstead's basement into his own well-stocked laboratory, and immediately began work on building the radio transformer.

In addition, Olmstead relied on Hubbard's engineering skills to help maintain his fleet of ships, boats, and vehicles. A popular story persists that Hubbard also equipped local taxicabs with radar equipment in order to help Olmstead's ships avoid capture, though this has never been verified. What is known is that Hubbard worked diligently on completing his project for Olmstead and, in October 1924, KFQX hit the airwaves as Seattle's first radio station. Powered by a 1,000-watt radio tower, Olmstead ran the station from an upstairs room in his house. The station would air nightly broadcasts consisting mostly of news and weather, followed by the popular "Aunt Vivian" program, in which Olmstead's wife, Elsie, would read bedtime stories to a dedicated base of local children. Their radio venture was given a boost when Hubbard constructed an additional studio at the top of the Smith Tower, allowing them to further commercialize the station and add live jazz music to KFQX's programming lineup.

While Seattle was celebrating its first radio station, Olmstead had gradually incorporated Hubbard into his smuggling operation, first as an apprentice -- teaching him the ins and outs of the bootlegging trade -- and eventually as one of his most trusted lieutenants. He taught Hubbard how to place orders with booze suppliers in Canada, as well as how to pick up the orders in rum-running boats. This placed Hubbard in a precarious situation when, on November 17, 1924, Olmstead's house was raided by federal prohibition agents. Hubbard was among those arrested and, as a result, was included in a grand jury indictment resulting from the raid. Feeling the heat from the upcoming trial, Hubbard approached William Whitney, the federal Prohibition officer in charge of assisting the prosecution, with a unique offer: He would become an informant against Olmstead in exchange for having his name quietly dropped from the indictment. In addition, he wanted to be appointed as a federal Prohibition agent. It was a bold proposal but, as Hubbard convincingly explained, his intimate knowledge of Olmstead's operation would all but ensure a guilty verdict.

The feds were desperate enough for a successful prosecution against Olmstead that they agreed to Hubbard's demands. With some hasty political maneuverings, Hubbard surreptitiously received an official appointment as a federal Prohibition agent on October 3, 1925. From that point forward, he worked for Olmstead's bootlegging operation during the day and would then covertly report information to the Prohibition Bureau at night.

According to later testimony given by Whitney, the Prohibition Bureau quickly became frustrated with Hubbard as he was hard to pin down for specific information and was rarely where he was supposed to be. Whitney described Hubbard as being "very eccentric." On Thanksgiving Day, 1925, the Bureau's skepticism was reinforced when Olmstead and Hubbard were arrested with a crew of bootleggers at Woodmont Beach, south of Seattle. They had been caught unloading a shipment of liquor by federal agents. When pressed on why he hadn't notified officials about this shipment, Hubbard offered the flimsy explanation that Olmstead had sprung the delivery on him at the last minute. This was the Bureau's first indication that Hubbard was playing both sides for his own self-interest.

Similarly, Olmstead was unaware that Hubbard was working as an informant. All that changed, however, when local papers outed Hubbard as a federal agent on May 16, 1926, with one article describing him as "a shadowy figure who works both sides of the street" ("Hubbard Working ..."). Hubbard's secret was now public knowledge. Yet after the news broke, he was somehow able to convince Olmstead that his work with the feds was actually done so he could act as a mole on Olmstead's behalf, and that his intentions were in the interest of protecting their bootlegging operation. Olmstead apparently accepted this explanation, as the two men continued to work together while Hubbard continued in his role as a Prohibition agent. Hubbard convinced the local bootlegging world that his role as an agent allowed him the opportunity to facilitate payoffs with federal agents in exchange for legal immunity. He was frequently known to accept payoff money from bootleggers with the promise that he could protect them from arrest. Wanting to retain his credibility as a Prohibition agent, he would then report these various booze rackets to the Bureau. A raid would then be organized, at which point Hubbard would tip off the bootleggers, allowing them the opportunity to escape. This way, Hubbard was able to collect money from both sides while, at the same time, making everybody feel like he was honoring their agreements. Even Olmstead -- looking for some leniency in his upcoming sentencing -- sold his house and gave all the money to Hubbard, who promised it would reach the right people. Olmstead would later receive a maximum, four-year sentence at McNeil Island Penitentiary.

Before reporting to prison, Olmstead sold his radio station. It was eventually purchased by local businessman Birt Fisher (?-1961), and it continues to exist as KOMO. Around the same time, Hubbard helped construct one of Tacoma's first stations, KMO, and began working on a new station for Olmstead, KXRO. The "RO" part of the call sign supposedly stood for Roy Olmstead. This new station was launched in Aberdeen but was shut down after a few months when authorities suspected it was being used to assist rum-running activity in Grays Harbor. In early 1927, Hubbard helped local personality Louis Kesley build another early Seattle radio station, KVOS.

Later that year, word of Hubbard's activities had reached top officials at the U.S. Justice Department, who were alarmed not only that someone of Hubbard's background had been made a Prohibition agent in the first place, but that he was continuing to work in an official capacity. This triggered an investigation, and on September 10, 1927, Hubbard was terminated from The Bureau of Prohibition.

By this time, Olmstead was behind bars at McNeil Island. Meanwhile Hubbard, no longer a federal agent, simply continued on in the bootlegging world. He operated north of Seattle, in Port Townsend, and in Aberdeen. It was in Aberdeen that Hubbard struck up a romance with Rita Scherer, whom he would eventually marry after divorcing his first wife. They married in Tacoma and, in 1928, their son, Alfred D. Hubbard, was born. At some point, Hubbard began working for a group of rum-runners from California who were smuggling large quantities of liquor into the country from an illegal distillery in Mexico. It was a multimillion-dollar criminal enterprise, and they hired Hubbard to build radio and communication devices for their ships. In 1936, the smuggling operation was raided by federal agents and Hubbard was arrested along with the others. After being tried and convicted, Hubbard was incarcerated at McNeil Island from September 21, 1936 through May 21, 1938.

World War II and the OSS

After his release from prison, Hubbard decided to stay on the legal side of things. He was able to earn a Master of Sea Vessels certification in California, which earned him the nickname "Captain Hubbard." His interest in sea vessels was likely a result of his prior involvement in the rum-running world, and he soon became the captain of a yacht in Santa Monica, and later took command of a charter boat called the SS Machigonne.

These maritime credentials, along with his known talent for electronic communications, attracted the attention of certain people involved in the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), a precursor to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). World War II had broken out in Europe, though the United States was still considered a neutral party as it had not yet entered the conflict. However, a secret mission was underway in which U.S. ships were quietly smuggled up to Vancouver, B.C., where they were then refitted and sent to England to be used as destroyers in the British Navy. President Roosevelt had approved of the operation a full year and a half before the U.S. officially entered the war, and Hubbard seemed like an ideal candidate, especially given his prior smuggling experience in Puget Sound.

Once again, Hubbard saw the potential opportunities in such a proposal and agreed to participate in exchange for a full presidential pardon for his earlier crimes. A deal was apparently struck, as Hubbard became directly involved in this covert operation from 1941 through 1947. As a cover, Hubbard moved to Vancouver, B.C., becoming a naturalized Canadian citizen and opening his own business, Marine Sales and Services. He was listed as director of engineering for this company, but this was subterfuge for his true mission. A popular legend holds that Hubbard was also involved in the Manhattan Project at the Hanford Nuclear Site in Washington, though there is no evidentiary support of this. By all accounts, Hubbard spent the entirety of World War II acting as America's man in Canada for this wartime smuggling operation with Europe.

In 1945, Hubbard was pardoned by President Harry S. Truman under Proclamation 2676 and, by the war's end, wartime profits had made him a millionaire. Wishing to continue his scientific pursuits, Hubbard established the Radium Chemical Company (later the Uranium Corporation) in Vancouver, which was dedicated to the marketing of radioactive elements. By all accounts, this was a family affair run by Hubbard, his wife, Rita, and their son, Alfred. Hubbard listed himself as "director of scientific research" for this new company and, in 1949, purchased his own private island off the coast of Vancouver. Hubbard transformed Dayman Island into the headquarters for his company, and used the 24-acre island estate to build his laboratory. This would all soon come to an end, however, when a new, serendipitous discovery changed Hubbard's life forever.

'The Johnny Appleseed of LSD'

In 1950, Hubbard was reading through a copy of The Hibbard Journal, a European science publication, when he stumbled across an article about a relatively unknown chemical compound called lysergic acid diethylamide. More commonly known by its acronym, LSD, this new substance was slowly but steadily gaining scientific interest due to its properties as a powerful hallucinogenic. Hubbard was instantly fascinated by what he read and was able to track down the researcher who wrote the article and obtain some of this substance for himself. Hubbard ingested some back at Dayman Island, resulting in a profound experience in which he decided to abandon the uranium business and dedicate himself entirely to promoting the use of LSD. He believed LSD to be a powerful utility for opening the human mind and was now on a mission to spread its use.

Hubbard traveled to Switzerland, where he purchased 10,000 doses of the drug from Sandoz Laboratories, and began introducing LSD to a wide assortment of people from all over the world. This included such thinkers as Aldous Huxley (1894-1963), whom Hubbard would strike up a longtime friendship, as well as Alcoholics Anonymous founder Bill Wilson (1895-1971). Hubbard introduced LSD to prominent psychiatrists in Hollywood who, in turn, would introduce it to many of their celebrity patients, including Cary Grant (1904-1986), Jack Nicholson (b. 1937), and Stanley Kubrick (1925-1999). Hubbard was known to travel with a leather satchel full of pharmaceutically pure LSD and, by all estimates, introduced more than 6,000 people to the drug, earning him the nickname "the Johnny Appleseed of LSD."

In one of the more fortuitous of these encounters, Hubbard also turned Myron Stolaroff on to LSD. Stolaroff (1920-2013) was a senior official at the Ampex Corporation, an early Silicon Valley tech company. As a result, Stolaroff himself became a huge proponent of LSD and would introduce the drug to many others in the early computer industry, including Apple co-founder Steve Jobs (1955-2011). It is said that a lot of early computer scientists were inspired by the use of psychedelics thanks, in large part, to Al Hubbard’s introduction of the drug to Stolaroff.

Hubbard began referring to himself as an LSD researcher and had dreams of setting up a series of clinics in order to train other LSD researchers. In 1953, he met with Dr. Humphry Osmond (1917-2004), a Canadian psychiatrist who was known for his research of hallucinogenic compounds. The two men developed a form of psychedelic therapy involving high doses of LSD and geared toward achieving a mystical or "conversion" experience for people seeking to overcome psychological trauma. Hubbard extended his practice of psychedelic therapy with Dr. Abraham Hoffer (1917-2009) at the University of Saskatchewan. He would later use this therapy for helping chronic alcoholics achieve sobriety in California, though there were accusations at the time that Hubbard charged high fees for his services and was being financially exploitative. Overall, though, his therapy was held in high regard by many in the psychiatric community. By the 1960's, Hubbard was enjoying an esteemed position at the Stanford Research Institute, where he was running special LSD sessions for a government think tank. This has led to speculation that Hubbard was involved in the infamous MK-Ultra experiments conducted by the CIA, though this has never been proven.

In 1967, the Drug Control Act was signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson, which made LSD a Schedule I substance. Those who were caught with LSD could now be charged with a felony punishable by up to 15 years in prison. As a result, laboratories and research facilities could no longer carry LSD nor use it for controlled studies or therapy. Without a means to support himself, Hubbard's finances were left in ruins and he was forced to sell Dayman Island.

Hubbard soon moved to an apartment in Menlo Park, California, where he focused his efforts on petitioning the FDA to allow LSD therapy for terminal cancer patients. He was unsuccessful in these attempts and, afterward, spent his last few years living in relative poverty in a trailer park in Casa Grande, Arizona. On August 31, 1982, Hubbard died alone at the age of 81. Despite dying in relative obscurity, Hubbard, in addition to building Seattle's first radio station, is now widely celebrated for his role in the popularization of LSD, as well as his indirect influence on the early computer industry in Silicon Valley.