The ghost town of Lester was founded in 1891 as a railroad stop on the western side of Stampede Pass. It eventually grew into a small but prosperous railroad and logging town in the early twentieth century. Changes in the railroad industry in the 1940s and 1950s caused the town to shrink significantly, a trend that was not reversed in the 1960s when a long and rancorous legal battle with the City of Tacoma over issues of road access to the town and water purity in the Green River watershed. In 1985, the last significant legal battles were lost by town residents and they held a public mock funeral for the town. The last resident left in 2002, and the town site is now a publicly inaccessible part of the Green River watershed.

Weston Becomes Lester

The town of Lester owed its existence to the construction of Stampede Pass in the 1880s. When the route opened in 1888, it brought a huge wave of new freight traffic and economic development up and down the railroad line, including the establishment of railroad support facilities such as stations and repair shops. When the route over Stampede Pass was completed, two helper stations -- Easton and Weston -- were established at each end of the relatively steep grade on either side the summit. Extra steam engines based at these stations, called helper engines, helped push heavy trains over the summit. Railway staff including telegraph operators, foremen, signal operators, and others worked full time at the helper stations. Eventually these workers brought their families to live with them near the stations, and communities began to form. As the rail traffic grew, so did the need for workers and rail facilities, and so did the towns' population.

Easton was located in an area that allowed for easy expansion and development. It still exists as an unincorporated community along Interstate 90 east of Snoqualmie Pass. Weston, however, was shoehorned up against a hillside just south-east of the confluence of the Green River and Friday Creek, at the mouth of Stampede Tunnel. With minimal room for expansion, the Northern Pacific Railway decided in 1891 to move the entire station a few miles west. Italian immigrant laborers helped construct at least a portion of the railroad works at the new station, before being fired in search of cheaper labor.

Lester Hansacker, a telegraph operator, lent his name to the new town. The telegraph call for the station was "DM," possibly an abbreviation for "Deans Mill," a shorthand name of Deans Lumber and Mercantile Co., which was located at the spot that became Lester.

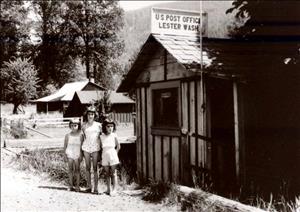

From 1891 to 1915 railway facilities at Lester grew to include a two-story combination depot, a six-stall roundhouse and machine shop, a section house for snow fighting crews, a roadmaster's home and office, housing for the section foreman, signal maintainer and agent, water and oil tanks, and a massive coal dock. Many of the railway crews doing this work, and their families, called Lester home. Around this nucleus congregated homes for railway crews, a school, a general store and post office, a small restaurant and grocery, a tavern, a hotel, an assistant ranger station, and at the eastern edge of town, the imposing home of Elmer Morgan, proprietor of the mill in the nearby town of Nagrom. By the 1920s, Lester would have a peak population of roughly 1,000.

Industries other than the railroad had an interest in Lester. Timber companies logged nearby claims and used the railroad to transport their products to market. The City of Tacoma, in dramatic political turmoil over having enough clean water for its growing population, claimed water rights on the nearby watershed of the Green River in 1910. After more bouts of public uproar, Tacoma built a dam and water intake just east of Palmer starting in 1911. The City of Seattle also claimed water rights in the area, primarily around the Cedar River watershed. During the 1930s, a Civilian Conservation Corp team built a logging road system which allowed residents of Lester and industrial interests to drive in and out of Lester, no longer solely reliant on the railroad for transportation.

Steam Engines Replaced by Diesel

In 1940, the Northern Pacific Railway tested a new diesel locomotive over Stampede Pass, and by the spring of 1944, the Northern Pacific purchased its first diesel locomotives for regular service. Diesel locomotives required far fewer crew members to operate, didn't require coal, needed less maintenance, and were cheaper to build and purchase than their steam-powered counterparts. While the switch to diesel resulted in more cost-efficient and cleaner railroad operations, ease of maintenance thinned the ranks of the workers required to support steam locomotives. Adding radios to diesels meant the end of telegraphers and depots as well.

Within 15 years, steam engines were no longer used on the Northern Pacific. With steam engines went the need for dozens of facilities and thousands of workers. Downsizing hit outlying posts such as Lester and Easton first, then larger shops in cities such as Auburn and Tacoma. With helper locomotives running directly from Auburn to Yakima, rather than being picked up at Lester or Easton, many railroad employees left Lester for Auburn.

In 1949 the U.S. Corps of Engineers recommended a dam be located at Eagle Gorge, a point roughly halfway between Palmer and Lester along the Green River. The building of a dam in that location would significantly alter the landscape between Lester and Palmer, as well as put any land purchased for the building of the dam under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Forest Service. The dam project spurred the City of Tacoma into action to protect its water interests in the area; beginning in 1957 it bought and condemned land flanking the Green River to protect it from further development and public encroachment.

Even as railroad jobs disappeared and construction projects ramped up, Lesterites showed faith in the future by rebuilding the 100-student-capacity Lester School in 1954 with $175,000 in private contributions. It was the social center of isolated Lester -- dances, movies, elections, and even church services were held there. The town's historic cemetery, which used 18-inch wood crosses to mark graves instead of stone markers, was located next to the school and was maintained by teachers and students.

The Battle of the Lester Gate

In October 1960, Tacoma and King County entered into a permit system restricting western road access into Lester. This included installation of a locked gate at the headworks. For the next two years, Lesterites grew increasingly frustrated about the gate, which cut off year-round automobile traffic between Lester and the rest of King County. Another access road was technically available to Lester residents -- the dangerous, 14-mile, single-lane gravel logging road that led east over Stampede Pass toward Cle Elum and was closed with snow for six months of the year -- but residents insisted that was not enough. Others agreed with them: In 1961 Lester was named Washington state's "most isolated town."

Lesterites and other public access advocates argued that the gate was not allowed under the federal Multiple Use Act of 1960, which made recreation a primary use of National Forest lands. Tacoma officials argued that allowing recreational use of the watershed lands would compromise water quality and require the city to build a costly filtration plant.

The lack of road access to Lester was the biggest issue for residents of the town, and tempers flared. Things boiled over on July 3, 1962, when a King County crew cut the 500-pound gate loose, tied a chain from the gate to the back of a county truck and drove away -- truck, chain, and gate. Two days later, King County sued Tacoma for blocking a public thoroughfare, claiming the county had held ownership of the road for 37 years. King County's suit against Tacoma ultimately fell apart, and in January 1965, the court finally ruled against King County. To protect its water interests, Tacoma brought suit against the Corps of Engineers and won in 1964; the dam became one of the few closed to public use.

Another suit, brought against Tacoma by George Welcker, questioned Tacoma's ability to condemn land on the riverfront. The condemning of land was even more upsetting to Lester residents than the road access issues, and the problem was further inflamed when Tacoma officials took callous-looking steps to secure these condemnations. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer reported that, "George Welcker, ill and 79, was under care at Seattle's Providence Hospital a few days ago when the City of Tacoma entered his sick room ... He was served with a petition for condemnation of his home and land ..." Lesterites formed a Save Lester Committee in an attempt to wage a legal battle of their own behalf, but tempers were high enough to suggest other forms of warfare. In a March 1964 interview, Lester resident Tom Murphy said, "You can't win in court against people like Tacoma, who have plenty of money. We’ll resort to shotguns if necessary."

In February 1965, Washington's Supreme Court upheld Tacoma's ability to condemn land and endorsed it as the best solution for protecting the water supply. The City of Tacoma was able to continue gating the western road from the headworks, condemning land along the river, and operating as it had been before the suits. Many residents of towns throughout the Green River valley sympathized with the Lesterites, and attended fundraisers meant to assist the beleaguered residents with legal fees.

King County tried again to claim title to the road into Lester in November 1965, but Tacoma eventually prevailed over the Corps of Engineers, King County, and Lester residents in court. The final blow came in 1967, when the Northern Pacific sold the town site of Lester to the City of Tacoma for $37,000. Lester residents living on former Northern Pacific property were given non-transferable lifetime leases. Thus, as the remaining 150 residents died or moved out, their homes were demolished by Tacoma.

Stampede Pass Closes

Lester steadily shrank as economic opportunities left the upper Green River region. The Northern Pacific Railway merged into Burlington Northern in 1970, which downgraded Stampede Pass in favor of other rail routes. The city of Tacoma made an agreement with local logging companies to not hire Lester residents, which forced some Lesterites to move away in search of paying work. Scott Paper closed its logging camp in 1978. Burlington Northern finally closed Stampede Pass in August 1983, severing the railroad connection and the need for any rail support along the Stampede route. The historic depot building became a King County landmark, and efforts were undertaken to remove the building to a new location where it could be used as a museum. The tiny school remained the largest employer in Lester, educating six students -- the children of two of the school's employees.

The 24 residents of the town still needed to obtain travel permits to use the all-weather access road leading west, but they were able to hold on to their community life thanks to the existence of the Lester School and its state-funded school district. Ironically, school district funding came from taxes on property owners in the district area, so the City of Tacoma was the largest contributor to the Lester School District's coffers.

In 1985, Representative Art Wang of Tacoma successfully passed a bill in the Legislature that, as an economic measure, consolidated small school districts such as Lester. Once consolidated into the Enumclaw school district, the school could no longer sustain itself and was closed. Enumclaw quickly sold the school property to the City of Tacoma, and the school's five employees found themselves out of work. In closing, the district transferred hundreds of thousands of dollars and a Snow Cat marked "Lester School Bus" to the Enumclaw School District.

The End of Lester

In the spring of 1985, current and past residents of the town gathered around a mock tombstone bearing the epitaph: "Here lies the town of Lester ... Killed May 22, 1985, by the pen of Gov. Booth Gardner -- hired gun of the City of Tacoma." By 1987, only two residents of the town remained.

Burlington Northern Santa Fe reopened Stampede Pass to freight traffic in 1996, but the trains now rode straight past the largely abandoned town of Lester on their way to Auburn. Gertrude Murphy, 99 years old and the last resident of Lester, was finally forced by ailing health to move out of the town permanently and died in 2002. The remaining buildings on the town site were burned and their foundations removed. The historic train depot, after initial difficulties, was purchased by a private citizen and converted into a residence outside the watershed. In 2015, Tacoma Public Utilities built the Green River Filtration Facility near its headworks on the Green River watershed. Today, the town site remains off-limits to visitors.