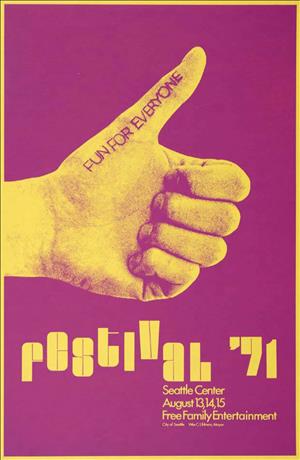

At noon on August 13, 1971, the Mayor's Arts Festival '71 -- to be redubbed Bumbershoot: The Seattle Arts Festival in 1973 -- commences with opening ceremonies at the Plaza of the States on the Seattle Center campus. Organized by Mayor Wes Uhlman's new Mayor's Festival Committee, Arts Festival '71 includes a wide array of arts and music selected to appeal to many different interests and sensibilities. Marketed with a simple slogan, "Fun For Everyone," the quirky festival includes "professional and amateur groups performing in crafts, fine arts and entertainment" ("Three-day 'Festival ..."). Among the attractions: "rock groups, jazz concerts, climbing exhibitions up the Food Circus exterior, a puppet show, art and photographic exhibitions, film festival, an 'oompa' band, free ice skating, magic-lantern show and indoor motorcycle races" ("Festival '71"). Best of all, most of these attractions are free to the public.

Mayor Uhlman Gets It Rolling

Newly elected as mayor of Seattle in late 1969, Wes Uhlman (b. 1935) soon attended a national conference of mayors in New York City and was impressed by the Mayor's Arts Festival that John Lindsay had produced there. At the time Seattle was beginning to suffer from massive layoffs at The Boeing Company – shockingly, more than 67,500 of the 100,000-plus jobs there evaporated in just two years -- and the impact would ripple through the local economy, causing many business closures and prompting waves of locals to move away. Uhlman needed to find ways to jolt the area out of its economic doldrums and the associated emotional and cultural malaise.

Summer was on the horizon and Seattle's traditional Seafair celebrations were feeling dated and not up to the task at hand. So upon his return home from New York, Uhlman shared his ideas with his staff and the brand-new Seattle Arts Commission, and then quickly formed a Mayor's Festival Committee, appointing attorney and KING Radio liberal talk-show host Irving M. Clark Jr. (1921-1978) to serve as chairman. Another founding member was attorney Peter LeSourd. It seemed that suddenly the whole town was talking about the need for a new arts-focused summer fair that would fulfill cultural needs that Seafair could not.

Clark welcomed ideas from a host of bright Seattleites. Among them were people with the Seattle Arts Commission (which included the noted painter Barbara Earl Thomas); Seattle Center director Jack Fearey (1923-2007) and his assistant C. David Hughbanks (1936-2023); the and/or gallery founder/curators Anne Focke (b. 1945) and Rolon "Bert" Garner; U District Center director Walt Crowley (1947-2007) and one of his staffers, Gilda Traylor, plus numerous others.

A World Festival of Music

In October 1970, The Seattle Times' urban affairs columnist Bruce Chapman (who would be elected to the Seattle City Council in 1971), articulated the emerging consensus on the possibilities for a new festival:

"Seafair was a wonderful expression of local boosterism in the 1950s. But Century 21 [the Seattle World's Fair of 1962] changed our tastes. And, anyway, the pre-eminence of our ties to the sea has diminished, and, in fact, so have the events during Seafair that are water-oriented. Very few valuable activities that are now occurring during Seafair couldn’t be better presented under a new format.

"I think we should now recover the spirit of the World's Fair and plan something spectacular, unique and prestigious; something that will enhance our international fame, attract tourist and their dollars, create year-around momentum for art and entertainment; something bold, fun, and adventuresome that will send a surge of optimism and excitement through the area.

"Seafair warmed over won't do. Neither will the kind of Pioneer Days pageant held in every other town west of the Mississippi. Nor will some glamorized carnival of local products, a Seattle version of other people's Pickle Celebration or Prime Beef Week."

"The sunny season fete would be the World Festival of Music, a civic burst of quality and quantity to satisfy every taste. The hub would be the Seattle Center," and the festival "would expose local and national audiences to distinguished new productions in symphony, opera, musical comedy, ballet, jazz, electronic music and other major art forms that are music-oriented ... The World Festival of Music would give us a fresh, inspired, mellow summer mood. Visitors would find the enchantment catching, they would come back for more. Our whole civic personality could be expressed and celebrated. It could be a magical time" (Chapman).

Modest Funds and Hopes

Starting with a modest budget of $25,000 -- and the hopes that a three-day Festival ’71 might attract 40,000 attendees -- the Mayor's Festival Committee envisioned an annual event that would expand over the years. One goal was to have it grow to a mature and stable state by 1976, when America's yearlong bicentennial celebrations would overlap with it. The budget seemed feasible in that many of the performers and presenters would appear as unpaid volunteers -- indeed all of the musical talents booked to play were locals, except for one headlining act.

The budget lacked much room for advance publicity -- the advertising push evidently amounted to a few press releases and the distribution of a simple poster. One week out from the fest's Grand Opening, The Seattle Times’ entertainment section initially listed it in its "Weeks events at Seattle Center" calendar as simply "Friday: Festival '71 -- various buildings / Saturday: Festival '71 -- various buildings." In the last few days leading up to the fair, more attention was devoted to it, but it was a late start. To many folks’ surprise, then, the 150 acts and activities booked for the fair ended up drawing an estimated 120,000 attendees. Festival ’71 was considered quite the successful launch.

Fun For Everyone

The range of entertainment provided to those multitudes of attendees was impressive. It included a native Northwest Kwakiutl ceremonial house installation at the Pacific Science Center, and appearances by the U.S. Forest Service's Smokey Bear mascot, the Mercer Island Puppeteers, the psychedelic Retina Circus Light Show, Scottish Dancers, Alaska's Cape Fox Dancers, the Seattle Boys Pipe Band, and what was billed as the "world's first electronic music instrument jam" (McDonald).

Among the local musical acts that performed was Joseph Powe's venerable African American gospel/doo-wop group, the Songcrafters, who roamed the grounds all day singing their spirited tunes. The old-timey Old Hat Band performed, as did the Misty-Aires Quartet, and Trudy Hawley's Banjo Band. The uncategorizable U District-based folk/freak ensemble, the Heady Lamar Hairington Band, arrived in its hippie bus and performed weird tunes at the Northeast International Fountain Court, while Northwest rock groups (Adam Wind, Bluebird, Child, Mojo Hand, Peece, Springfield Rifle, and Stone Garden), a funk band (Cold Trane), and jazzniks (the Overton Berry Trio, Danny Ward Quartet, and Seattle trumpet legend Floyd Standifer) were also included.

One measure of Seattle's relative provincialism is that Festival '71's organizers evidently believed that the old southern hillbilly music/humor duo, Homer and Jethro, could suffice as the headlining concert draw. We will never know because mere days before the fair opened, Homer (Henry D. Haynes) died, and a fill-in novelty act, Sheb "The Purple People Eater" Wooley, was quickly substituted. Other acts on that Opera House bill were local bluegrass pioneers, the Tall Timber String Band, and Jerry Jack Adams and the Country Rebels.

Things To Do

In addition to a "Hot-Pants Contest," ceramics and fencing and logging demonstrations, there was the cutting-edge "Contact: The Northwest" multimedia/art offering presented at the Flag Plaza Pavilion. As curated by Anne Focke, it included "a mélange of art objects borrowed from various exhibitions in the past year," plus laser beams, computers, paintings and sculptures, a light show by Los Lites -- and electronic music via various early synthesizers and sound generators, not to mention a 20-foot long guitar as played by the Land Truth Circus art collective (Voorhees).

In short: Everyone had plenty of fun, even the media critics and pundits who all rushed to publish their descriptions of Festival '71 as "a 'populist grab-bag,' a 'smorgasbord of experience,' a 'multimedia extravaganza,' a 'big box of gift chocolates," and "'the metropolitan telephone book'" (Dorpat).

The Seattle Times weighed in with a glowing review:

"In spite of just about everything, the consensus seems to be that the hastily-put-together 'Festival '71' was a success. There was very little money, there was no central theme, there was too little publicity, there really wasn’t anything THAT special -- and yet the whole thing seems to have radiated good vibrations and the Seattle Center teemed with more friendly people -- 120,000 of them -- than there have been in that locale since the halcyon days of the Seattle World's Fair. ... Unlike Seafair, where one is supposed to be content to sit and wave at the silly fake royalty, Festival '71 had things for people to do ..." (Voorhees).

Other Tales …

Interestingly, the Empty Spaces Association mounted a theatrical piece -- "The Wax Monkey and Other Tales" -- at the Center Playhouse. That "organization" was a subset of the Pike Place Market-based Empty Space Theatre crew -- some of whose longhaired participants would soon help form the One Reel Vaudeville Show. That troupe would be included the following year among the performers at Festival ’72. One Reel – formalized as a production company -- would thereafter be contracted to produce many subsequent years worth of the fair, which would be rebranded in 1973 as Bumbershoot: The Seattle Arts Festival -- one of the world's great international music and arts gatherings.