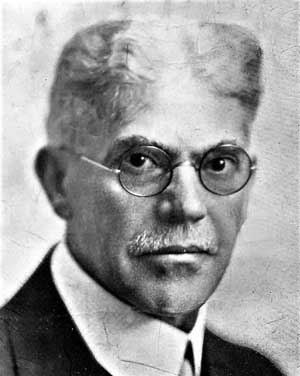

On September 19, 1913, Whatcom County Superior Court Judge Edward E. Hardin (1860-1940) challenges newspaper editor Frank Sefrit (1867-1950) to a duel. Sefrit, editor of Bellingham's morning paper, the American-Reveille, as well as its evening paper, the Bellingham Herald, has published critical commentary of what he perceives as the judge's inaction in a criminal case pending before him. A Sefrit editorial in that morning's American-Reveille sends the judge over the edge, and he angrily confronts the editor outside of his office. Though no duel follows, a gleeful Sefrit makes sure the judge's challenge gets plenty of press.

Crusader or Hell Raiser?

Sefrit cut his writing chops just as a sensational writing style known as "yellow journalism" became popular in the 1890s. Perfected by nationally known newspaper editor William Randolph Hearst (1863-1951), this style emphasized sensationalism over facts, and Sefrit was quick to adopt it. He used it to great effect to argue for causes he believed strongly in, as well as to assail his adversaries, which he also believed strongly in. In November 1911 he became editor of Bellingham's two largest newspapers, the American-Reveille and the Bellingham Herald, and wasted no time introducing himself to the city's readers. Viewed by some as a crusader and by others as a hell raiser, Sefrit went on to make his mark on Bellingham's history over the next 40 years.

On September 19, 1913, Sefrit published an editorial in the American-Reveille about a local criminal trial in which he argued that the prosecuting attorney, Frank Bixby, had a conflict of interest. Sefrit (and others) had called for the presiding judge, Edward "Ed" Hardin, to appoint an outside prosecutor in the case, but Hardin had declined. Hardin was a respected judge who was well-known throughout Bellingham; between 1900 and 1903 he had served two terms as mayor of New Whatcom and Whatcom (New Whatcom became Whatcom in 1901, which then merged with Fairhaven in December 1903 to form a new city, Bellingham). This meant nothing to Sefrit, who loudly attacked Hardin in his papers. In his September 19 editorial, he suggested that Hardin "assert himself" ("'Powerless.'" Stuff!").

"I'll kill you like I would a snake"

Already seething from Sefrit's prior attacks, Hardin erupted when he read the veiled assault on his masculinity. At midday he went to Sefrit's office and confronted him outside of the front entrance of the American-Reveille building. "Judge Hardin Invites Editor to Fight Duel" shouted the top trailer in the next morning's issue of the American-Reveille. Wrote Sefrit in an accompanying front-page article titled "Superior Judge Challenges Editor to Mortal Combat:" "[Hardin] proposed fists, daggers, shotguns, pistols, derringers, daggers or pocket knives ... 'You will have to change the policy of your paper,' declared the irate judge, 'or I'll kill you like I would a snake ... you are a character assassin and a criminal,' shrieked the judge" ("Superior Judge ...").

Sefrit portrayed himself as a master of cool. His article reported:

"Judge Hardin nervously sought comfort in his side coat pocket and the editor suggested that it was not necessary for him to arm himself -- that the judge was a much larger man physically and should not require fire arms. The judge was assured that it had come to the editor repeatedly that the judge had bought a revolver and had threatened violence. 'Yes, I have a gun but I did not get it for that purpose. In fact I have three guns, and I'll use them too, damn you' [Hardin responded]. The editor thought one was sufficient for the average man. 'You've been publishing things about me -- dirty insinuations, that are damn lies' declared the gentle dispositioned superior judge" ("Superior Judge ...").

The heated discussion continued for about 20 minutes, and finally ended when Sefrit invited Hardin into his office to review his coverage with an offer to correct any factual errors.

"He replied that he had not had his luncheon and had already said enough, to which the editor assented ... The editor has repeatedly and kindly assured the judge that he disliked very much to call attention to his conduct, but that the editor believed it was his duty to do so regardless of the unpleasant sequels of such a controversy" ("Superior Judge ...").

The Buzz of Bellingham

Despite this innocent disclaimer, Sefrit made sure he called attention to the judge's conduct in that afternoon's Herald and in the American-Reveille the next morning. He continued the coverage with a barrage of editorials over the next few days, and claimed that he'd received numerous letters of support. "Dueling in Whatcom County appears to be very unpopular, judging from the almost unanimous verdict against the recent proposal of the Superior Judge to meet the editor in mortal combat. Even Judge Hardin's closest friends deplore the act of the judge of the criminal division. And we suspect the Judge himself is ashamed of that aberration," Sefrit crowed ("Self-Provoked Criticism").

The confrontation was the buzz of Bellingham for awhile, but it blew over and became one of many Sefrit stories. Hardin remained on the bench in Whatcom County for years, and enjoyed a long and well-regarded career before his death in 1940. Sefrit didn't go anywhere either. He stayed on as editor of the American-Reveille (which stopped publishing in 1914) and the Bellingham Herald until 1950, championing his causes and antagonizing his enemies until he was slowed by old age and cancer in the 1940s. After his death in 1950, his sons Charles "Chick" (1895-1965) and Ben (1906-1984) managed the Herald through 1970.