On May 10, 1980, the three Columbia Basin Irrigation Districts -- the Quincy, East, and South -- enter into an agreement whereby they will construct, operate, and maintain powerplants at several locations related to the Columbia Basin Project (CBP). The CBP delivers water to approximately 700,000 acres in central Washington and represents the single largest reclamation project in the United States. The powerplants will use the water from the CBP's 333 miles of main canals, which drop over 1,000 feet over the length of the project. The first of these seven powerplants will enter service in 1982, and the last in 1990. Owned and maintained by the Irrigation Districts, the powerplants will be managed by the Grand Coulee Project Hydroelectric Authority, which will later be named Columbia Basin Hydropower. The power from five of the projects will be purchased by the cities of Tacoma and Seattle, while two other projects will be operated and maintained under contract with the Grant County Public Utility District.

First Half of the Columbia Basin Irrigation Project

The history of the Pacific Northwest's exploration has been inherently tied to the Columbia River Basin. On May 11, 1792, Robert Gray (1755-1806), a fur trader and the first American to circumnavigate the world, sailed the Columbia Rediviva into the river's broad estuary. He renamed the river from Wimahl ("Big River") to the Columbia River after his ship. As the first documented ship to anchor in the river, the United States had a claim to discovery that led to the Oregon Treaty of 1846.

The Columbia River's strategic location along the west coast of North America and its combination of enormous flow and rapid fall created economic opportunities for the entire region. The approximately 1,200-mile long river flows through multiple mountain ranges and solid rock that was carved by the repeated floods at the end of the last Ice Age. It drops steadily about 2 feet per mile. These conditions are uniquely situated to create hydroelectric energy potential, with its rocky canyons providing ideal footings for dams.

Plans to tap the hydroelectric energy potential on the Columbia River were produced during the early 1930s by both the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Bureau of Reclamation. While the plans differed in recommending federal involvement and implementation strategies, both produced a plan for the pumping of water that would eventually feed a series of canals in order to irrigate farmland in the Columbia Plateau. Both plans acknowledged the need for hydroelectric power to subsidize irrigation water on the semi-arid plateau.

After internal debates about the direction of the project, members of Franklin D. Roosevelt's (1882-1945) administration agreed to the Bureau of Reclamation's proposal of a high dam that would provide both hydropower and irrigation water. The planning and early construction of the Grand Coulee Dam and Columbia Basin Irrigation Project occurred during the Depression through World War II, when, despite the collapse of economic institutions, Americans took faith in large-scale technological endeavors that posed the image of humans conquering nature. Construction of the Grand Coulee Dam was undertaken in two stages: The first stage included the dam and two powerhouses; it began in 1933 and was completed in 1951. The second stage consisted of the third powerhouse, which began in the mid-1960s and was completed in 1975. Construction of the first stage of the Columbia Basin Irrigation Project began in 1945 and was largely completed by 1955.

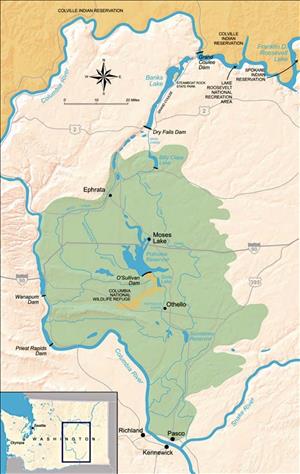

The water that flowed for the first time in August 1951 was pumped through a series of canals, tunnels, inverted siphons, and reservoirs to irrigable land. Because the Columbia River flows at a distance between 60 and 150 miles from irrigable land, water was pumped up from Franklin D. Roosevelt Lake (also known as Lake Roosevelt) into the Grand Coulee near where the ancient river bed flowed during the Ice Ages. The main canal was attached to the lower end of Banks Lake, the 27-mile-long equalization reservoir formed between two earth and rock dams behind Grand Coulee Dam. Banks Lake was named in honor of Frank A. Banks (1913-1957), the Bureau of Reclamation's construction engineer in charge of the Grand Coulee Dam's construction.

Following Banks Lake, the water flowed across the project area by gravity with supplementary pumping throughout a system of canals. The water flowed southward from Banks Lake at Dry Falls Dam in the main canal toward the northern end of the irrigable land and made a spill 165 feet over Summer Falls into a reservoir named Billy Clapp Lake. The water left the reservoir and flowed into another canal, which forked into the west and east lines of the canal system. The west canal ran 88 miles to Soap Lake, through Ephrata, Quincy, and George. The east canal ran 87 miles south to the Potholes Reservoir, Othello, the Wahluke Slope, and to Scootenay Reservoir. Potholes Reservoir was located near the center of the project area, formed by the construction of O'Sullivan Dam. Several wasteways captured run-off, which was returned to the system at Potholes Reservoir.

Small Scale Hydroelectric Power Plants

The three Columbia Basin Irrigation Districts -- the Quincy, East, and South -- were formed in 1939 to support farmers in the financing for the construction of water-supply systems and to act as a mortgaging agency for those seeking Bureau of Reclamation water. After six years of negotiations, on December 18, 1968, the Bureau of Reclamation transferred the operations and maintenance responsibilities of the irrigation and drainage facilities to the districts and stated that the districts, with the permission of the Secretary of the Interior, "may build plants for the production of power and energy structures and facilities necessary for the operations of such plants" ("Irrigation Districts" 2019). This language made explicit the knowledge of the hydroelectric power potential found in the Columbia Basin Irrigation Project canals.

Small-scale hydroelectric projects were initially delegated to the South Irrigation District led by Secretary-Manager Russel D. Smith. In 1975, Harry Hosey, the manager of water resources for Tudor Engineering Company in Seattle, initiated a study for the feasibility and potential of small-scale hydroelectric power. Smith remained unconvinced of the economic viability and likely approval of the required government permits, until 1977, after periodic prodding from Hosey.

A prototype project at site P.E.C. 22.7 was chosen for the first small-scale hydroelectric generating facility. Located 22.7 miles south from the beginning of the main irrigation canal in the South Irrigation District, it would serve as the test run for the six future projects in navigating the regulatory and environmental requirements. The estimated project cost for P.E.C. 22.7 was $3.5 million to $4 million and the energy it produced would cost 1.5 cents a kilowatt hour. Compared to the existing system of City Light generating electricity on the Skagit River, the proposed project cost several times more per kilowatt hour, but less than generating electricity in nuclear power plants.

In August 1977, Smith and the Tudor Engineering Company began the process of applying for permits and searching for a funding partner. While awaiting approval from the Secretary of the Interior, which took two years and "a great deal of arm twisting," they continued with the other required Washington State licenses and permits and the application to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission in order to reserve the site (Schwartz 1980). In December 1978, the cities of Seattle and Tacoma and the three irrigation districts entered into a formal agreement for the purchase of power from P.E.C. 22.7. The two cities would pay the cost of producing the power plus a fixed fee for the districts.

Name Change: Columbia Basin Hydropower

The first half of the Columbia Basin Irrigation Project marveled at humans' ability to conquer nature and showed this enthusiasm with the willingness to spend exuberant amounts of money on large-scale projects, whereas the attitude in the 1980s for the hydroelectric generating facility projects was that of tight capital, impending energy shortages, and public distrust about costly and large-scale technological undertakings. Rather than "conquering nature" as the first half of the Columbia Basin Irrigation Project aimed to achieve, the South Irrigation District's strategy in the 1980s was to harness the energy that was already present in the water running through the canals, drains, and wasteways.

After five years of studying the feasibility of the hydroelectric generating facilities and undergoing the legal, regulatory, and environmental requirements of the P.E.C. 22.7 prototype project, the Board of Directors of the three Irrigation Districts entered into an agreement on May 10, 1980, for the development, operation, and maintenance of hydroelectric generating facilities to be developed on the Columbia Basin Project's irrigation systems. In addition to the development, operation, and maintenance of hydroelectric projects, the agreement covered division of power revenues, creation of the Grand Coulee Project Hydroelectric Authority and designation of the South District as lead agency until the Grand Coulee Project Hydroelectric Authority was created and operational.

The first of the seven powerplants, the prototype PEC 22.7, entered service in 1982, and the last entered service in 1990. The generating facilities would produce electricity only during the irrigation season, which ran from March 15 through October 30. While the irrigation season usually paralleled a period of reduced demand for the utilities, the excess was stored in the large hydro reservoirs and at hand during dry years. Alternately, the power was sold or traded as electricity needs in cities varied between summer and winter, and year to year.

After the South Irrigation District had begun the initial developments of the hydroelectric generating facilities, the Grand Coulee Project Hydroelectric Authority was created and organized by the Irrigation Districts in 1982 as a separate legal entity. Effective July 1, 2015, the Grand Coulee Project Hydroelectric Authority changed its name to Columbia Basin Hydropower, headquartered in Ephrata. Columbia Basin Hydropower performs operation, maintenance, and administrative functions for five of the seven hydroelectric projects owned by the Districts. The generation of these five projects is purchased by the City of Seattle and the City of Tacoma. The five hydroelectric projects include:

- Main Canal Headworks – P2849: Located at Banks Lake, this is the beginning of the entire irrigation canal. (Capacity megawatts [MW] = 26; started January 1, 1987).

- Summer Falls – P3295: Located where the entire system flow takes a large elevation drop into Billy Clapp Lake. (Capacity MW = 92; started January 1, 1985).

- Russell D. Smith – PEC 22.7 – P2926: A check structure located 22.7 miles downstream from the Headworks where the canal elevation is lowered to accommodate a drop in terrain elevation. (Capacity MW = 6.1; started September 1, 1982).

- Eltopia Branch Canal (E.B.C.) 4.6 – P3842: A chute which accommodates a drop in terrain elevation 4.6 miles downstream from the point where the Eltopia Branch merges with the Potholes East Canal. (Capacity MW = 2.2; started May 1, 1983).

- Potholes East Canal (P.E.C.) 66.0 – P3843: A long wasteway return chute 66 miles downstream from the headworks where water collected from a high irrigated area drops 304 feet into the Columbia River. (Capacity MW = 2.3; started March 1, 1985).

Columbia Basin Hydropower provides Federal Energy Regulatory Commission liaison support and administrative functions for two of the seven hydroelectric projects owned by the Districts. The two hydroelectric projects include:

- Quincy Chute – P2937: Located near the 40-mile mark on the West Canal (Capacity MW = 9.4; started October 1, 1985).

- Potholes East Canal (P.E.C.) Headworks – P2840: The outlet to Potholes Reservoir at O’Sullivan Dam. (Capacity MW = 6.5; started September1, 1990).