On August 5, 1968, Washington Governor Daniel J. Evans (1925-2024) gives the keynote address at the Republican National Convention in Miami, Florida. Evans, 42, is chosen to give the address to represent a new and dynamic face of the Republican Party in 1968. He gives a speech described by The Seattle Times as "an articulate call for change," and one that remains relevant more than 50 years later.

Low-key but Dynamic

Dan Evans got his start in politics when he was elected to the Washington State House of Representatives in 1956. He demonstrated an early ability to work well with others regardless of their political views, and later served two terms as the Republican minority floor leader. Evans ran for governor in 1964, and despite guarded expectations -- he was not much of a glad-hander when it came to meeting crowds (during the race, a few wags nicknamed him "Old Gluefoot") -- and a nationwide Democratic landslide that year, handily defeated incumbent Governor Albert Rosellini (1910-2011). At age 39, Evans became the youngest governor in the state's history. He and his family moved into the governor's mansion in January 1965.

Despite his low-key style, Evans swiftly became known as a dynamic governor. During his first term (1965-1969) he initiated a $242 million school construction program, promoted self-help ventures in the poverty-stricken Central District in Seattle, helped establish air and water pollution controls, and worked to preserve and increase recreational areas in the state. There were minuses in his first term as well. He infuriated ultraconservatives when he denounced the state's John Birch Society early in his first term, and he had his woes with a legislature that was dominated by Democrats during his first two years in office.

But these were minor minuses, and Evans developed a reputation as a straight shooter with a steady hand. It wasn't long before Republicans outside of the state began to notice. He was one of three governors selected to work on the Republican Coordinating Committee, which was created by the Republican Party in 1965 in an effort to reenergize the party after its drubbing at the polls in 1964. Evans was responsible for leading efforts to elect more Republican governors in 1966, and it worked -- the party picked up eight governorships nationwide in the elections that November.

'Nobody Had Talked to Me'

In addition to electing more governors, the Republicans sought to build a more powerful group of governors. At a meeting of Republican governors in 1967, Ohio Governor Jim Rhodes (1909-2001) suggested that some of these governors might want to play more of a role in the 1968 Republican National Convention than the nation's governors had traditionally played. It would introduce them to the rest of the country, give them an opportunity to shine in the national spotlight, and perhaps lead to bigger Republican victories down the road. In a 2016 interview with MyNorthwest.com, Evans described how he was chosen to deliver the convention's keynote address: "[Rhodes said] '... Let's tell 'em we want the keynote address, and I think Evans would be a good guy to give it. He's young and new.' He just blurted that out. Nobody had talked to me at all" ("Washington governor's ...").

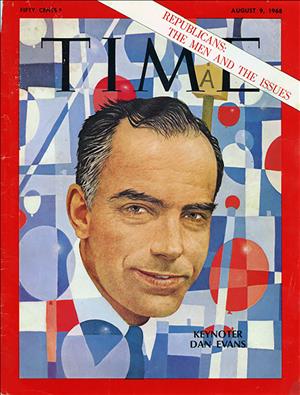

The advent of television in the 1940s and 1950s changed both how keynote addresses at national conventions were given and how the public perceived them. Before television, these speeches were known for plenty of flowery but meaningless oratory, sometimes given by well-known speakers, sometimes not. This changed by the 1960s -- Ronald Reagan (1911-2004) gave the keynote address at the 1964 Republican National Convention -- and by 1968 an opportunity to give the keynote address was considered a springboard to publicity and bigger dreams. As the convention approached in the summer of 1968, Evans, at 42 still relatively young compared with many of the governors then in office, photogenic, and articulate, found himself in a considerably brighter spotlight than he was in the Evergreen State. He was featured in Time magazine in its August 9, 1968 issue (which came out just before the convention began), and this increased his visibility further. There was even some talk that he might be chosen to be the vice presidential candidate, but this was a long shot in 1968, and one that he was not particularly interested in.

Evans began preparing for the address in earnest two months before he would deliver it on August 5, 1968. He was determined that it would be different from the standard overblown oratory and attacks on the opposition that keynote addresses were usually known for, and he took a broad approach. He read other keynote addresses, sought out advice from various party leaders, and tried out phrases of his speech in other speeches he gave throughout the Northwest that summer. He finally invited some advisers and friends to Olympia the week before the speech for a preview, though it wasn't quite finished. Someone suggested that Evans add a few more crowd-pleasing, oratorical touches designed to bring the audience to its feet, but he vetoed the idea, explaining, "We ought to aim at the people who are watching on television, rather than delegates who won't be listening anyhow" ("Keynote to Opportunity").

Evans confirmed his decision when he wandered the convention hall before his speech and sized up the acoustics, which he found to be sorely lacking, so much so that shortly after his speech he told The Associated Press that he thought half the crowd at the convention hadn't been able to hear him.

Evans was hardly alone when it came to keeping the delegates' attention at the convention. As The Seattle Times explained in an article describing actor John Wayne's (1907-1979) appearance to give the invocation during the session on Monday morning, August 5, "John Wayne accomplished what few other speakers could at the convention: he got the delegates to listen to him during the reading" ("G.O.P. First Session ..."). However, there was another, and unexpected, hiccup that affected Evans's speech more directly. He was originally scheduled to speak at about 8 p.m. Eastern Time, but this was changed at the last minute, partly at the request of Evans, who wanted to give the speech an hour or so later in order to have a better chance at reaching a wider television audience in Washington state. But a large number of speakers that evening caused the schedule to slip even further, and shortly before Evans spoke the 1964 Republican candidate for president, Barry Goldwater (1909-1998), gave a red-meat speech attacking President Lyndon Johnson (1908-1973), and received a five-minute standing ovation from the crowd.

Evans appeared after Goldwater. By this time it was nearly 11 p.m. in Miami and the delegates were tired and restless. In describing the crowd's reactions to Goldwater and Evans, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer sniffed, "Goldwater got a thunderous ovation ... Evans got a few courteous cheers." Shrugged one delegate, "After Goldwater, what can you do?" ("Evans Calls ..."). Nevertheless, after a lengthy introduction by New York City Mayor John Lindsay (1921-2000), Evans went on to give a speech that has since grown in stature, as predicted by former Pennsylvania governor William Scranton, (1917-2013), who told Time magazine that week, "I bet him a buck that when he made his keynote speech there wouldn't be any big hoopla. I bet him that it would take the delegates a day -- 24 hours -- to realize that he had much to say" ("Keynote to Opportunity"). Evans himself said years later, "I'm proud of that speech. I think it is the best of my career" ("The Keynoter").

In many ways the theme of the speech and Evans's statements could have been written and spoken just as easily in 2019 as in 1968; take out his references to Vietnam and youth unrest and it becomes even harder to discern that the speech was given more than half a century ago. Focusing on the dizzying pace of change in the country in the 1960s and how the Republican Party should respond, Evans asserted:

"Today, as never before, the nation demands new leadership: the fresh breeze of new energy; a full and honest reassessment of national goals; a new direction for its government, and a new hope for its citizens ... [we are burdened by] a crisis of violence and stolen hope, a crisis of lawlessness and injustice, an impulsive, reckless dissatisfaction with what we are -- and a desperate outcry for what we could be once again. Above all, we are now witness to the disintegration of the old order ... Instead of the makers of history, we have become the victims of history -- urged but not led, promised but not given, heard but not heeded.

" … [Our nation] began in revolt against the tyranny of an old and rigid order, and our institutions have remained strong, not by clinging to the past, but by adapting to the future -- by giving substance and direction to the heritage of liberty and independence. .. It is time now to reach inward -- to reach down and touch the troubled spirit of America.

" … The protests, the defiance of authority, the violence in the streets are more than isolated attacks upon the established order; they are the symptoms of the need for change and for a redefinition of what this country stands for and where it is going ... Let us proceed [with] the knowledge that what we do here well may determine the fate of a nation. Let us debate not in fear of the present, but with faith in the future" ("Text of Governor's ...").

'An Articulate Call for a Change'

The speech lasted for just under half an hour, and as Evans had predicted, many of the delegates milled around, chatting, smoking, reading newspapers, and not paying much attention. In an unintentional compliment the following morning, Seattle P-I reporter Shelby Scates (1931-2013) wrote that the speech was "better suited for television" ("Evans Calls ..."), confirming Evans's belief that television was more likely to attract an attentive audience. Scates noted that the substance of the speech was "remarkable for a keynote in that it did not belabor the Democratic Party or revel in Republican glories" ("Evans Calls ..."). The Seattle Times described it as "an articulate call for a change in direction that -- as it turned out -- read much better in text than it could be read from a platform" ("Rockefeller Gets Boost"). Unlike the P-I, the Times was impressed enough with the speech to reprint it in full in its edition that day.

Spokane's Spokesman-Review wrote approvingly, " ... the young governor of Washington state had the nerve the other evening to deliver a keynote address that will be noted for perceptive political realism rather than bombastic hypocrisy" ("Political Realism ..."). Jack Pyle of the Tacoma Tribune took it a step further a few days later and wrote, "The thought behind the speech was among the best thought presented at the convention. The written speech itself could go down as historic ... The delegates and the American people heard it once more before the convention was through. And that was in the acceptance address of Richard M. Nixon, which in content and purpose was Evans's speech all over again" ("Lot of Things ...").

The speech was slightly eclipsed in Washington state by Evans's endorsement the following morning of Nelson Rockefeller (1908-1979) for the Republican nomination for president. A number of the state's Republicans were incensed by the endorsement, especially since there was considerable support for the more moderate Richard Nixon (1913-1994), who was favored to win the nomination. King County Republican headquarters was deluged with calls from unhappy Republicans the day after the speech, with nearly all of the calls focused on Evans's endorsement; some callers threatened to vote for segregationist George Wallace (1919-1998) if Rockefeller was the Republican nominee.

Nationally, the speech attracted considerable editorial commentary. The Chicago Tribune claimed that the speech was "flat and without passion," while the Miami Herald similarly dismissed it, writing "any hopes [Evans] might have had for a vice presidential nomination were also finished. Evans had issued a call for the party to look to the future ... and the party faithful ignored him." The Washington Post was more judicious, writing "[The speech] was singularly free from the flatulence and the stem-winding rhetoric that has seemed so inescapably a characteristic of this peculiar art form ... on the contrary, he dealt with the real and immediate social problems, exhorting his party to 'rise to the challenge created by the winds of a new direction.' That kind of talk hasn't been heard in Republican conventions since Teddy Roosevelt." Veteran Atlanta Constitution publisher Ralph McGill (1898-1969) described the speech as "a magnificent address, but a majority of the convention's delegates had ears only for the Nixon mind and strategy" ("The Keynoter").

Afterward

The convention proceeded more or less as expected. Nixon won the nomination, defeating both Rockefeller and an upstart Ronald Reagan, who managed to attract some attention late in the campaign and who some briefly thought might have had a shot at stealing the nomination from Nixon. But the Republicans in 1968 were not ready for a candidate as conservative as Reagan, especially after a similarly conservative candidate, Barry Goldwater, had lost so badly at the polls in 1964. Probably the biggest surprise of the 1968 Republican National Convention was Nixon's selection of relatively unknown Maryland governor Spiro Agnew (1918-1996) to be his vice president.

The Nixon-Agnew ticket went on to win a close election that November, and won again more handily four years later. However, the 1972 election was the pinnacle of both men's careers: Agnew resigned in disgrace in October 1973, while Nixon resigned in similar disgrace (though for unrelated reasons) a scant 10 months later. Dan Evans fared far better. He served three consecutive terms as Washington's governor, the first in state history to do so, and again was considered as a potential vice presidential candidate at the 1976 Republican National Convention. After he left the governor's office in 1977, he served as president of Evergreen State College until 1983. In September 1983 he was appointed to fill a U.S. Senate seat to replace Henry "Scoop" Jackson (1912-1983), who had died suddenly earlier that month. Two months later Evans was elected in his own right in a special election, but he chose not to run for reelection in 1988. He published an essay in The New York Times Magazine that spring explaining why: "I have lived through five years of bickering and protracted paralysis. Five years is enough'' ("After a long ...").

Evans's political career ended in January 1989, but he hardly stopped working. He opened a consulting firm in Seattle a few months later and never looked back. He served on the University of Washington Board of Regents from 1993 to 2005, and he served on at least a dozen corporate, education, and non-profit boards well into the 2010s. In 2019, he and his wife Nancy (b. 1933) lived in Seattle and remained active in the community.