Founded in 1890 by pioneering woman doctors Eva St. Clair Osburn and Ella Fifield, the White Shield Home was a maternity hospital for unwed mothers. Its first patient was an expectant girl found in labor pains on the platform of the Villard train station in Tacoma; she was cared for in Dr. Osburn's home. With Osburn and Fifield soon joining forces, the White Shield Home outgrew Osburn's living room and two other larger facilities before moving into a permanent home in 1916, a grand Colonial at 5210 S State Street in South Tacoma. The home prospered there for decades, until the state declined to renew its license in 1956 due to mismanagement. Reopened in 1960 and renamed Faith House, the facility continued to serve as a maternity hospital until 1987. In 2019, the building's owners nominated the site for Tacoma's Local Register of Historic Places.

Alone in the Night

The White Shield Home began in 1890 with the discovery of a young woman in labor pains on the platform of Tacoma's Villard train station, located at the triangular corner of Jefferson and Commerce streets. There in the darkness she was about to give birth to her first child. She was there because she apparently had no better place to go, having been barred admittance to hospitals because she couldn't pay for services. Dr. Eva St. Clair Osburn (1857-1937), a Tacoma physician, learned of the girl's dire condition and ushered her to her home, where she cared for the mother and her newborn into the night. They were then boarded in Osburn's home at no cost, until the mother could reenter society successfully.

Several weeks prior to this incident, Tacoma had welcomed two new physicians, a husband-and-wife team of William Fifield and Ella Fifield. The couple had relocated to Tacoma from California with the desire to establish a practice in a burgeoning community in which they could make a profound impact. When Ella Fifield arrived, she was the fifth woman to establish a medical practice in the south Puget Sound. News of the desperate mother and child so moved Fifield that she reached out to assist in any way possible. She and Osburn were thus joined by a common cause: Mothers themselves, they set out to ensure that regardless of age or social status, women were afforded an opportunity to become mothers with dignity.

The Osburn residence was at 302 East 26th Street, adjacent to the historic Tacoma fire station. The first official White Shield Home was dedicated at a rented facility some eight blocks away, at 34th and H Street. This home was located on the fringes of Tacoma in a neighborhood that would later become known as McKinley Hill. But the house could accommodate only six girls comfortably. Thomas L. Nixon, a perennial Tacoma mayoral candidate known for his anti-Chinese rhetoric, was the home's immediate benefactor, but after he died suddenly prior to renegotiation of the lease agreement, White Shield's temporary home got tied up in probate. A longer-term solution needed to be found quickly.

Thanks to a donation by Tacoma real estate mogul Allen C. Mason and his wife Libby, the maternity home was relocated to 4214 N Huson Street in 1892. But as charitable as the Mason's gift was, the home on Huson, which provided room and board for 15 patients, was soon inadequate. It would continue to operate until a permanent home could be found.

Temperance and Charity

Osburn and Fifield were active members of the Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). Perhaps not coincidentally, the Tacoma Chapter of the WCTU was formed immediately after the drama with the unfortunate young mother on the train platform. The WCTU had two overarching principles. First, the golden rule found in the book of Leviticus: "Thou shalt love they neighbor as thyself." Second, the classical Greek philosophical mantra of "all things in moderation and not to excess." For the WCTU, these guiding principles inspired the organization to advocate for women regardless of class or race, a platform manifest in the suffrage movement.

The success of winning voter rights for Washington women in 1910 later empowered the WCTU and other progressive feminist organizations to seek the prohibition of alcohol. Alcohol was villainized as the tool of abusive men, and Fifield and Osburn were known for their strong stance on prohibition. They championed women's causes in Tacoma and nationally. WCTU members were advocates for widows and orphans, and often brought their issues before the state legislature.

One goal of the WCTU was to meet the needs of all unwed pregnant women and girls in Washington, and for this, the White Shield Home badly needed a new location. In 1915, the organization launched a statewide fundraising campaign. Donations rolled in a dime here and a dollar there, from every county in the state, until nearly $30,000 had been raised to finish construction. The Tacoma Daily Ledger reported, "The new building will be one of the finest of its kind in the West. It will have a thoroughly modern maternity hospital with room for 20 patients and quarters will be provided for 20 other patients" ("Pretty Site Sold …").

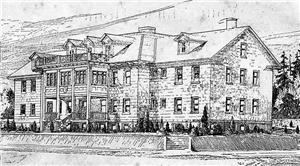

The WCTU hired architect George W. Bullard (1855-1935) to design the hospital. Educated at the University of Illinois, Bullard began his career working with his brother in Springfield, Illinois, before moving to Tacoma to be his own boss in 1890. He was a founding member and president of the Washington chapter of the American Institute of Architects. Bullard's resume included hundreds of homes and dozens of church buildings, including the Tacoma Buddhist Temple. He also produced drawings for the Washington State College in Pullman.

Dedicated in 1916, Bullard's new White Shield Home was situated on a crest at the corner of 52nd and State Streets in Tacoma. It was a Colonial Revival style building, two and half stories tall. Prior to the construction of Interstate 5, the property boasted territorial views of Wapato Lake to the east and Mount Rainier to the south. It was two blocks from the South Tacoma streetcar line, which linked the flanking neighborhoods Fern Hill and Edison with Tacoma. The building's grounds were expertly landscaped, with parklike plantings and comfort amenities including an outdoor fireplace, barbeque, and quiet areas for patients.

During the White Shield Home's years of operation, women and girls came from as far south as Clark County in southwestern Washington. A Native Alaskan girl was known to have given birth there. The home was a refuge for women marginalized by Victorian-era morals. The Seattle Post Intelligencer reported, "The home … is supported by voluntary contributions from its friends, not being distinctly a Tacoma institution, but extending its benefits to all parts of the state" ("White Shield Home").

White Shield's Inner Workings

The mothers-to-be were often admitted to the White Shield Home in the second trimester of their pregnancy, and they and their babies were typically discharged four weeks after delivery. Girls were accepted regardless of their age, race, religious affiliation, or ability to pay. But the patients' behavior was evaluated against a standard. They would be barred admittance if they had a criminal record or an established pattern of behavioral issues. While under the care of the home, the patients were given room, board, and medical attention.

Each patient had her own room and slept in her own bed. For some, this was their first taste of personal privacy: a door that closed, and a single bed. According to newspaper accounts, the youngest girl accepted in the home was 11. The oldest unwed mother admitted was 36, and the average age of patients was 17. The Tacoma News Tribune referred to White Shield as the "Home of New Beginnings," adding, "where unfortunate girls of every color and creed are welcomed into an inspiring life of rehabilitation and modern maternity care" ("Girls' Home Hospitable").

School-age girls continued their public education at the facility and were given an opportunity to learn a vocation if they wished, along with homemaking skills. Patients were expected to perform routine household chores and were encouraged to participate in daily non-denominational chapel and worship services. These services were provided by the patients themselves and not led by either the church or hospital employees.

Upon delivery, White Shield Home staff members urged the girls to keep their babies. But societal views generally were not conducive to unmarried young women keeping babies without family support. Various newspaper reports referred to White Shield's patients as "ignorant," "inmates," "offenders," "fallen," "erring," and "weak." So when a responsible father expressed an interest in the mother and the child, marriages were arranged. If the child's father did not step forward, the home sought to give the baby to family members before considering the final alternative, adoption by local couples.

Fates of the Founders

In addition to her role in founding the White Shield Home, Ella Fifield founded the Tacoma Parent Teachers Association, and in 1890 became the first woman elected to the Tacoma School Board. In her position on the board, she participated in negotiations with the Northern Pacific Railway for the purchase of the Tacoma Tourist Hotel, which the school district converted into the current Stadium High School. Later in life, she became an insurance auditor who defended women and orphans when insurance companies were reluctant to pay their claims.

Fifield was widowed in 1907 after 32 years of marriage. She lived at 1920 N Steele Street from approximately 1904 until 1919, when she relocated to the Midwest. In 1919, she accepted the position of National Medical Examiner of the Woman's Benefit Association, the first association dedicated to providing life insurance for women. She served an eight-year term reviewing insurance cases at the organization's national headquarters in Port Huron, Michigan. The women-run company, re-named Woman's Life (and still going strong), boasted more than $18 million in assets in 1925.

Fifield returned to Tacoma in 1929, perhaps to be closer to her daughter and son-in-law, Mary and Harry Tracy, and her two grandchildren. She was living in a home at 3219 N 30th Street at the time of her death in 1933. Of her, the Tacoma News Tribune wrote: "A notable career ended here yesterday with the passing of Dr. Ella J. Fifield, 82, identified in Tacoma medical circles for 44 years" ("Dr. Ella Fifield Called …").

White Shield's other founder, Eva St. Clair Osburn, was raised and educated in Iowa and received a license to practice medicine in Washington Territory in 1889. She and her husband Albert were members of the Tacoma Freemasons Society and ardent supporters of the Orting Soldiers Home. She was a prominent lecturer for the WCTU. The couple had two children, William Quincy Osburn and a second child who apparently died in infancy. Albert Osburn died in 1923, after which Eva retired from community service and moved to California. She died on July 5, 1937, at age 80.

White Shield Ends, Faith House Carries On

During the White Shield Home's latter years of operation, the attending physician was Annie Reynolds. Statistics from 1948 suggest the relative effectiveness of the home during her tenure. It was reported in the year 1948 that 64 girls were admitted as patients and 49 babies were born on the premises, with others born off-site due to complications or medical transfers. Of the 49 newborns, 36 were placed with adoption agencies, 11 were kept by their mothers, one died, and another baby's fate was unknown at the time the data was collected. An anonymous patient wrote in 1949, "I sincerely hope that the girls who enter and leave your care may gain, as I did, not only the freedom from a misdeed, but that they may better know themselves and their fellowmen and look forward to a brighter and richer future, as a result of their association with your home" ("Tacoma Agency Helps …").

The White Shield Home operated with a nearly spotless record for four decades, until the State of Washington refused to re-issue a license for the hospital in July 1956. Based upon audit findings, the state cited two compelling reasons for the refusal: insufficient staffing of certified professionals, and a confusing and disorganized management scheme. The facility was constantly staffed by a licensed attending physician and a registered nurse. However, to keep costs low, and to be prudent with donors' resources, volunteers (some of them former inpatients) were called upon to assist with hospital operations. This willingness to substitute volunteers for certified professionals was troubling to the state. Also troubling: White Shield's management featured two boards of directors – the WCTU board, representing the property owners and fundraising arm of the hospital, and a separate board responsible for the day-to-day operations. The state ruled this system was cumbersome and unsustainable.

The absence of a state operating license was a death knell for the White Shield Home. The facility was soon shuttered, and the property sold to Dr. Charles Arnold, a geriatric physician who renamed the facility Laurelhurst Nursing and Convalescent Center. Arnold immediately began making alterations to the building, which originally faced east to greet the morning sun. Under Arnold's ownership, the orientation was changed to the north in 1957. A portion of the parklike grounds was sacrificed for a parking lot. A less formal entry was added to the southern elevation. The grand entryway and second story sunroom were sacrificed when 20 new patient rooms were added to the front elevation of the building in 1957. Arnold held the title of director during Laurelhurst's brief period of operation; he was also responsible for the construction of at least three other convalescent centers in Pierce County, one each in Westgate Center, McKinley Hill, and the Browns Point neighborhoods.

Meanwhile, the need for a maternity hospital for unwed mothers became increasingly evident with the closure of the White Shield Home. By 1959, a Tacoma News Tribune article estimated 500 teenage girls would become pregnant out of wedlock in Washington that year. "It is extremely difficult for a social worker to tell a girl there is no room for her," said Mrs. Leonard Frank, former chairwoman of the WCTU. Besides medical attention, Frank outlined other needs in a home for unwed girls. "These girls are teenagers. They have all the frustrations of teenagers and just aren't equipped for daily living" ("Church to Back …")

In 1960, former members of the White Shield Home board of directors, working with the Rev. J. Irving McKinney, head of the Olympia Diocese of the Episcopalian Church, founded an organization for the benefit of unwed mothers known as Faith House. McKinney helped spearhead a two-year mission to fund a replacement after the dissolution of the White Shield Home, and he was instrumental in acquiring the $50,000 in matching funding necessary to reacquire the original property from Arnold. McKinney was then elected president of Faith House by its board.

Reborn in 1960, the facility operated successfully and continuously as a maternity hospital until 1987, by which time public funds and annual charitable contributions from organizations such as the United Way were being channeled away from faith-based organizations.

The White Shield Home, and later Faith House, maintained an impeccable record when it came to maternity care for unwed mothers and their babies. An estimated 4,000 girls were helped by the two organizations from 1890 to 1987. During that interval, the infant mortality rate of the White Shield Home was 0.002 percent, a rate that any hospital in the U.S. would be proud to boast. For comparison, nearly 100 years later, the national average of infant mortality had reached a low of 0.006 percent by 2014.

Decay and Preservation

Ten years following the closure of Faith House, the City of Tacoma embarked upon a South End Planning Study. Surveyors of Tacoma's South End neighborhood immediately identified the White Shield Home building as a historically significant structure and potentially eligible for listing to the National Register of Historic Places.

The building had fallen into an accelerated rate of decay after years of disuse. Columbia Bank seized the property in foreclosure before selling it in a short sale in 2014. Two years later, the building was sold to Le Khahn, a property developer whose associates subdivided the property, cleaving the once beautiful grounds from the home and converting the land into 11 residential building lots. While new homes popped up on the landscape, Khahn spun off the main building to Dream Northwest Properties of Kent in 2018.

Dream Northwest, a minority woman-owned real estate development and management firm, recognized the significance of the home to Washington state women's history. Dream Northwest sponsored the effort to have the building listed as a Tacoma Landmark and to seek special valuation for its ultimate rehabilitation. In 2019, the White Shield Home was recognized by the City of Tacoma Landmarks Preservation Board for its architectural significance, the role it played in the care of the state's unwed mothers, and for the careers of Eva St. Clair Osburn and Ella Fifield, its influential founding doctors.