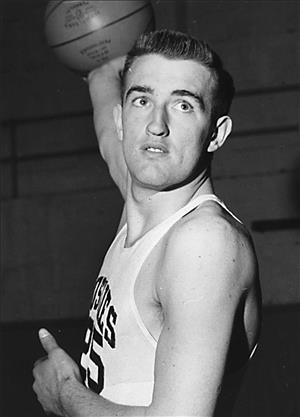

Bob Houbregs is the most decorated men's basketball player in University of Washington history. A record-setting scorer and consensus All-American known for his long-range hook shot, he led the Huskies to their only appearance in the NCAA Final Four as a senior in 1953. He was the first Washington basketball player to be honored by having his jersey number retired. Houbregs was taken with the second pick of the 1953 National Basketball Association draft, the highest for a UW player until 2017. His professional career ended after five seasons because of a back injury. After his playing days he worked for the Converse athletic shoe company and had a short stint as general manager of the NBA's Seattle SuperSonics. He was elected into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 1987. His Washington scoring records stood for decades and two of them -- most points in a season and most in a game -- are still standing

From Canada to Queen Anne

Robert "Bob" Houbregs was born on March 12, 1932, in Vancouver, British Columbia, the son of John and Mary Houbregs. John was a minor league hockey player. When Bob was 2 he was diagnosed with rickets, a painful bone disease, and the prescribed treatment involved breaking his legs. The toddler spent 10 weeks in a cast and, as his mother put it, "had to learn to walk all over again" ("If Houbregs Had Health!").

In 1935, John Houbregs joined the Seattle Sea Hawks of the Northwest Hockey League, and the family moved to Seattle's lower Queen Anne neighborhood. Bob went to Warren Avenue Grade School and then Queen Anne High School, where his mother managed the cafeteria and he earned all-city honors in basketball and baseball. Several colleges wanted him, but his father helped make it a simple choice. "I never really thought about going anywhere else but Washington," Houbregs said. "My dad told me if I was going to live in Seattle there was only one place to go" ("Wayback Machine").

Houbregs entered the university in 1949. Freshmen did not become eligible to play NCAA varsity basketball until 1972, so his first-year points did not count toward what would become a record-breaking career total. He and his fellow freshman teammates gave a preview of things to come, winning 21 games and losing only two. Head coach Art McLarney (1908-1984) resigned before their sophomore year and was succeeded by Tippy Dye (1915-2012), who had just coached his alma mater, Ohio State, to a conference championship.

Learning the Hook Shot

Dye recognized Houbregs' potential and began teaching his young center the hook shot. Unlike the set shot and jump shot, which are taken facing the basket, the hook is launched with the player standing sideways, his shooting arm fully extended behind him before sending the ball in an arc over his head toward the hoop. Dye had Houbregs take 200 hook shots at every practice session. The results were revolutionary.

"Houbregs didn't invent the hook shot; he just customized it in a way that was near impossible to replicate ... The UW's lanky 6-foot-7 Houbregs regularly prowled the perimeter and catapulted them from what later became 3-point range. It was an intricate basketball ballet. He should have received four points for each make, considering the degree of difficulty involved, but they were still worth just two. He became Seattle's most unique basketball player of any generation" (Raley, 43).

In his first season on the varsity, 1950-1951, Houbregs led the Pacific Coast Conference's Northern Division in scoring with 13.6 points per game and made the all-conference team. The Huskies posted a record of 24-6, won the conference championship and made it to the national quarterfinals -- the highest finish to that point in school history -- with their lanky sophomore center shooting the hook both left- and right-handed. Dye urged him to concentrate on one going forward. Houbregs picked his right. He also went on a milkshake diet, boosting his weight from 200 pounds to 215 for his junior season. He averaged 18.6 points and again made the all-conference team. Washington repeated as regular-season PCC champion with a 25-6 record.

The only downside for the Huskies was losing the best-of-three conference championship series to UCLA, denying them a return trip to the National Collegiate Athletic Association tournament in a year when the Final Four (the national semifinals and championship game) would be on Washington's home court, Edmundson Pavilion. "I sold programs outside, that's all I did," Houbregs said. "I didn't want to go in. My heart was still broken" (Raley, 44).

Becoming a Legend

The Huskies responded to that disappointment with a 28-3 record in Houbregs' senior season (1952-1953), winning their third straight conference championship and a second trip to the NCAA national playoffs. They averaged 72.3 points, a school record that stood for 14 years, and outscored their opponents by 13.2 points per game, still the most by any Washington team. Houbregs dominated the competition all season. He set school records by averaging 25.6 points and scoring 49 against Idaho. He was a consensus first-team All-American and the Helms Foundation NCAA Player of the Year, the only Husky ever to receive those honors.

In the Idaho game, Houbregs broke the conference scoring record by 10 points and the Edmundson Pavilion record by six. When the game ended, members of the crowd -- 11,600, Washington's biggest of the season -- rushed onto the court to mob him. Newspaper coverage reflected the excitement.

"Fantastic Bob Houbregs put on the greatest basketball performance ever seen in the Pacific Northwest Saturday night. ... Houbregs not only broke Jack Nichol's single-game record but plastered virtually every mark for an individual," wrote the Seattle Post-Intelligencer ("Hooks 49 New Mark").

"The feat of Houbregs, an amiable giant with what has been described as the nation's best hook shot, eclipsed any one-man performance ever seen here," The Seattle Times reported. Its account described the aftermath: "Players and fans hoisted the weary, grinning Houbregs to their shoulders and carried him triumphantly to the Washington dressing room, each man savoring the tremendous scoring feat as if it were his own" ("Houbregs Scores 49 ...")

The Huskies capped their season by sweeping California in the conference championship series and earning a spot in the 22-team NCAA tournament. Oddsmakers picked them as the favorites to win it.

Reaching the Final Four

The NCAA West Regionals were played at Oregon State's Gill Coliseum. Washington's first opponent was Seattle's other major college team, the Seattle University Chieftains, whom the Huskies knew well but had never before faced. The Huskies had their All-American in Houbregs; the Chieftains had two -- center Johnny O'Brien (b. 1930) and his twin, guard Eddie O'Brien (1930-2014). The O'Briens had led Seattle U. to a shocking victory over the touring Harlem Globetrotters the previous year, which suggested the Chieftains could beat just about anyone. Interest in the Washington-Seattle U. matchup was great enough that KING-TV covered it live, the first time a local station televised a game played out of state.

The contest did not live up to the hype. Washington jumped to an early lead and won easily, 92-70. Houbregs set an NCAA tournament record with 45 points. He followed that with 34 points against Santa Clara, sending the Huskies for the first and only time in school history to the national semifinals. (The term Final Four was not officially adopted until 1975.)

The games were played at Kansas City, with Washington paired against Kansas and Indiana facing Louisiana State. Kansas had won the national championship in Seattle in 1952, and was coached by the legendary Phog Allen (1885-1974). Realizing that the key to beating Washington would be to control its star, Allen told his players to jump into Houbregs' path whenever he got the ball. The result, on March 17, 1953, was stunning. Houbregs was charged with four personal fouls in the first half and a disqualifying fifth early in the third quarter. He left having scored just 18 points. It was the first time he had fouled out in 57 games and led to Washington's most lopsided loss in his three seasons. The Huskies collapsed without him, losing 79-53 in a game where the stakes were never higher.

Washington managed to regroup and routed LSU the next night, winning 88-69 to finish third in the nation. Houbregs scored 42 points, giving him the three highest single-game totals in Husky history, including the ones against Idaho and Seattle U.

He finished his college career with a three-year total of 1,774 points, a school record that would stand for 34 years. The following month, April 1953, the University of Washington announced that his jersey number (25) would be retired, making him the first Husky basketball player to earn that distinction.

Turning Pro

Listed as a 6-foot-7 center, Houbregs was selected by the Milwaukee Hawks with the second pick in the 1953 National Basketball Association draft. After only 11 games, he was traded to the Baltimore Bullets. In his second pro season, he played for three teams -- the Bullets, the Boston Celtics, and the Fort Wayne Pistons. Between those unsettling seasons, he married Ardis Aloha Olson, his college sweetheart.

Houbregs' longest and most successful NBA stint was with the Pistons. He played for them for two full seasons, 1955-1956 and 1956-1957, averaging 11 points. He helped them reach the NBA Finals in 1956. The Pistons moved to Detroit in 1957. On December 1, Houbregs slammed into a basket support in New York, severely injuring his back. He spent some time in the hospital and never played another game. He was only 24.

His NBA career over, Houbregs returned to his alma mater in March 1958 as an assistant coach. He later went to work for Converse Rubber Company, best known as a maker of basketball shoes. He also ran a summer basketball camp on Whidbey Island.

Houbregs had been working for Converse for 11 years and was director of sales and promotions when the SuperSonics came calling. Seattle's NBA team was struggling through its third season. Its general manager had resigned in September 1969, leaving guard Lenny Wilkens (b. 1931) not only in the dual role of player/coach but also as interim GM. Houbregs was hired as general manager, effective December 1, 1969. The Sonics finished with a 36-46 record that season, improved slightly to 38-44 the next, and in 1970-71 posted their first winning record, 47-35.

Despite the team's modest success, Houbregs traded away Wilkens, a future Hall of Famer as both a player and a coach, and hired Tom Nissalke (1932-2019) to replace him as coach. The Wilkens trade was widely unpopular, and the team fell apart, finishing the season with a 26-56 record. Nissalke was fired, and in May 1973 Houbregs was forced out and replaced by former Boston Celtics great Bill Russell (1934-2022), who was hired to be both general manager and coach. (Wilkens later returned to Seattle as the Sonics coach and in 1979 guided them to their only NBA championship.)

Collecting Honors

Houbregs resumed working for Converse after leaving the Sonics. In 1979, Washington created the Husky Hall of Fame, and he was part of the inaugural class. His career scoring record lasted until February 6, 1987, when 7-foot center Christian Welp (1964-2015) broke it, benefitting from having four seasons to reach that milestone. The record fell 10 minutes into a game against rival Washington State. Action was stopped so the crowd could applaud Welp's accomplishment. Houbregs was there to shake the new record-holder's hand.

On May 5, 1987, nearly 30 years after he stopped playing, Houbregs achieved the highest honor in basketball. He was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. His classmates -- Rick Barry (b. 1944), Walt Frazier (b. 1945), Pete Maravich (1947-1988), and Bobby Wanzer (1921-2016) -- were former college standouts who starred in the NBA. Houbregs was nominated by the hall's Old Timers Committee based solely on his college career. California coach Pete Newell (1915-2008) told the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, "Bob Houbregs changed the game of basketball with his hook shot" (Raley, 44). In 2000, the Vancouver native was inducted into the Canadian Basketball Hall of Fame.

Houbregs died at age 82 on May 28, 2014 in Olympia. He was survived by Ardis, his wife of 60 years, four sons and three grandchildren. Husky officials remembered him as not only a game-changer, but as a warm and popular individual.

UW athletic director Scott Woodward called him an icon who "helped put Washington basketball on the map, but what made him remarkable was his character beyond the game of basketball" ("UW Legend ..."). Coach Lorenzo Romar (b. 1958), who had known Houbregs since the early 1980s, called him "kind of a connector between the old and the new" of Husky basketball ("So Long ..."), and said he would remember him for "how gentle of a man he was. He wasn't a softy when he played. He was out there wreaking havoc. Off the floor, as a man, he was as caring and humble as you want to find" ("UW Legend ...").