On August 7, 1938, Dr. Harmon Talley Rhoads Jr. (1911-2001) of Everett says goodbye to his father at Boeing Field in Seattle and boards an airliner for a flight to New York City. In New York, he will join the fourth Ellsworth Antarctic Expedition as medical officer. There are a total of 19 expedition members including Australian-born explorer Sir Hubert Wilkins (1888-1958), American millionaire Lincoln Ellsworth (1880-1951), Canadian chief pilot J. H. Lymburner (1904-1990), Canadian reserve pilot Burton J. Trerice (1913-1987), radio operator Frederick Seid (1906-?) of New York, and the Norwegian operating crew of the 135-foot expedition ship Wyatt Earp. Together they will endure violent storms and nearly two weeks with their ship imprisoned in the ice before reaching the coast of Antarctica. Their purpose is to conduct a flight over the continent of Antarctica and claim territory for the United States.

Father and Son Doctors

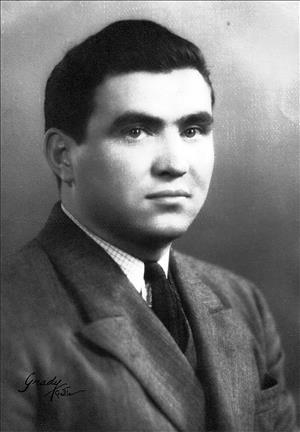

Harmon Talley Rhoads Jr. was born in Hazen, Arkansas, on November 10, 1911. The next year his family moved to Montana where his father, Dr. Harmon Rhoads Sr., had an eye, ear, nose, and throat practice. In 1924, the Rhoads family with Harmon Jr. and his three brothers -- Charles, James, and John -- moved to 1620 Rucker Avenue in Everett. Later the family moved to 2404 Hoyt Avenue, across from Everett High School. By 1939 they had moved to a brick home on Cavaleros Hill about three miles east of downtown Everett with a wonderful view of the Snohomish River Valley and the city of Everett in the distance.

Dr. Rhoads Sr.'s first Everett office was in the First National Bank Building at Hewitt and Colby avenues. He later moved to the new Medical-Dental Building, one block north on Colby Avenue. He was active in the Everett Elks Lodge and other organizations. Rhoads Sr. died in 1941 and is buried at Evergreen Cemetery in Everett.

Harmon Rhoads Jr. graduated from Everett High School in 1929, a year ahead of schoolmate Henry "Scoop" Jackson (1912-1983). He graduated from the University of Washington and then the University of Oregon medical school. In July 1938, he completed his residency at New York's Flower Fifth Avenue Hospital and went home to Everett for a vacation of hunting and fishing.

The Ellsworth Antarctic Expeditions

This 1938 expedition was preceded by three others. In the 1930s, Lincoln Ellsworth had his sights set on achieving the last remaining polar "first": a flight across the continent of Antarctica. There would be four Ellsworth Antarctic Expeditions conducted between 1933 and 1939. In all cases the goal was for Lincoln Ellsworth and his pilot to fly across the continent. The first expedition in 1933-1934 ended prematurely after their main airplane was damaged when the ice it was sitting on gave way, dropping the fuselage into a crevasse and damaging the skis and one wing. The second expedition in 1934-1935 ended when engine repairs delayed the flight until weather conditions made the snow fields too thin to support a safe takeoff. Finally on the third expedition in 1935-1936, Ellsworth's flight across the continent was successful. At this point Ellsworth decided that he wanted to go back for a fourth expedition in order to claim 80,000 more square miles of territory for the United States.

Famed Explorer Leads the Expeditions

George Hubert Wilkins (1888-1958) was a famous polar explorer who, with North Dakota pilot Lt. Carl Ben Eielson (1897-1929), made exploratory airplane flights over the Arctic north of Barrow, Alaska, from 1926 to 1928. They frequently landed on the sea ice and took soundings to determine the ocean depth at those locations. They were the first to prove that there was no land, only ocean covered by sea ice, in the area between Alaska and the North Pole. In April 1928 they made the first airplane flight across the Arctic Ocean from Barrow, Alaska, to Spitsbergen, Norway, a distance of 2,200 miles.

Lincoln Ellsworth had inherited a fortune from his father. He wanted adventure and fame as an explorer but did not have the skills or endurance to achieve that on his own. What he lacked in skills, he made up for in money and vision. At the same time there were explorers such as Sir Hubert Wilkins with the skills but not the resources. Ellsworth had helped fund the 1931 Wilkins-Ellsworth Trans-Arctic Submarine Expedition and Wilkins, feeling indebted to Ellsworth for his past financial support, agreed to organize and conduct the Antarctic expeditions in Ellsworth's name.

Wilkins Recruits an Everett doctor

As technical adviser and organizer, Wilkins was responsible for finding a skilled crew for the 1938-1939 Ellsworth Antarctic Expedition. Since he lived in New York City, Wilkins sought advice about a medical officer from doctors at Flower Fifth Avenue Hospital in (now known as the Terence Cardinal Cooke Health Care Center.) They recommended Dr. Harmon Rhoads Jr., so Wilkins flew to the West Coast to interview him as well as other possible candidates in Vancouver, B.C., Denver, and San Francisco.

On July 28, 1938, Wilkins arrived at Boeing Field in Seattle to interview Rhoads, but the young doctor missed the meeting. He was on a fishing trip in the mountains. Disappointed, Wilkins flew on to Vancouver to interview another candidate. On his return through Boeing Field the next day, Rhoads was there to complete the interview.

Wilkins offered the medical officer position to Rhoads, who accepted. The doctor told reporters that a trip to Antarctica had not been a childhood goal, but Wilkins, the world famous explorer, had selected him. Since he had just finished his internship and not yet established his own medical practice, he accepted the opportunity for adventure.

The crew list document from the expedition indicates a unique arrangement concerning Rhoads's payment for his work. Rather than sending all or some of payment to banks or relatives at home as done with other crew members, Rhoads received his full pay on board, directly from Wilkins.

Off to Antarctica

Two airplanes were loaded on the expedition's motor vessel Wyatt Earp at Floyd Bennett Field in New York. The larger airplane was a Northrop Delta monoplane in which the pilot Lymburner and Ellsworth would fly over the continent. The smaller airplane was an Aeronca seaplane used to scout the shoreline to find a suitable area for the expedition base and a runway for the Northrop flights. The ship with expedition members departed from New York on August 16, 1938, for Pernambuco, Brazil, arriving there on September 13 to load supplies. It then sailed to Cape Town, South Africa, arriving on October 9.

On October 29 they left Cape Town for the Indian Ocean coast of Antarctica. The voyage was marked by violent storms and pack ice much farther north than expected. They spent 45 days struggling through 800 miles of thick sea ice, including 13 days when the ship was imprisoned in ice unable to move. They arrived at the edge of the Antarctic continent on January 1, 1939.

Continued bad weather slowed their search for a suitable runway location along the coast. They eventually found one and on January 11, 1939, were able to make their exploratory flight of 210 miles into the continent using the Northrop plane. During the flight, Ellsworth dropped a brass canister containing a note claiming 80,000 square miles of territory for the United States. Continuing storms prevented more flights, and the U. S. government chose not to pursue the territorial claim.

Work for Dr. Rhoads

In December, while still en route to Antarctica, the youngest sailor on board, Harold Ronneberg, was performing a gymnastic demonstration for the entertainment of the crew when he fell from the horizontal bar and struck the deck, severely cutting his scalp. Rhoads treated the wound with 15 stitches. Ronneberg healed with no permanent effects and once bandages were removed was able to resume his normal watch.

In January, three crew members were swept into the water by rough seas while they were out on an ice floe to collect ice to melt for fresh water. All were rescued but the Chief Officer Lauritz Liavaag's leg was caught between chunks of ice, crushing his knee and breaking his knee cap. Rhoads determined that hospital surgery was required. Ellsworth decided to end the expedition and return to the nearest port, a journey that took 21 days.

On February 4, 1939, they arrived at Hobart, Tasmania. Surgery was performed at the Royal Hobart Hospital by Dr J. F. Gaha (1894-1966), the Tasmanian Minister for Health; and Dr. V. R. Ratten, assisted by Rhoads. While the surgery was considered successful, Liavaag ultimately lost use of the injured leg and had to live afterwards on seaman's disability payments.

End of the Adventure

Ellsworth disbanded the expedition at Hobart and sold the Wyatt Earp to the Australian government for surveying the Australian coast and exploring Antarctica. The ship had served him well on four voyages totaling over 86,000 miles, the equivalent of three times around the world.

This was the last privately funded Antarctic expedition and the last for Wilkins and for Ellsworth, who died in 1951.

After the expedition, Rhoads returned home to Everett accompanied by Trerice, and Seid. They celebrated at the Rhoads family home sharing stories and pictures of their seven-month adventure and their new penguin friends. The March 11, 1939, issue of The Everett Daily Herald reported their return with a front-page story and photo. The March 12 issue of The Seattle Times carried additional photos and stories. The voyagers told reporters that they would like to return to Antarctica, but World War II ended such expeditions.

Life After Antarctica

Rhoads practiced medicine with his father at the Medical Dental Building in Everett for about two months before returning to New York City to study plastic surgery. He served in World War II as a plastic surgeon in the U. S. Army Air Force, specializing in treating burns and injuries from explosions.

After the war, Rhoads practiced in New York City and eventually became chief of plastic surgery at Metropolitan Hospital and at New York Medical College. He married and had a daughter, Victoria, and a son, George. Victoria was his medical assistant for many years in his office on East 83rd Street in Manhattan, across Fifth Avenue from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. They often enjoyed visiting the museum together during off hours. She also remembers as a child viewing his talks and slide shows of Antarctica. George, also a doctor, learned the art of Bonsai from his father, who was a Bonsai Master. Both Victoria and George remember their father as an avid outdoorsman enjoying the skills he learned in the mountains and lakes of the Pacific Northwest during the time he had lived in Everett.

After retiring, Rhoads moved to St. Petersburg, Florida, where he died on May 7, 2001.