Beginning in 1969, the Boeing Company, after a decade of rapid growth in air travel, began laying off employees due to oversaturation of the airplane market. As airplane sales continued to decline, the company teetered on the verge of bankruptcy, leading to deeper cuts in every department. Then, in 1971, the U.S. government cut funding to the company's supersonic transport (SST) program, and the project was cancelled soon after. By the time that layoffs ceased, Boeing had lost more than 60 percent of its workforce. Because the aerospace company was the region's largest employer, the downturn had a ripple effect in the local economy, and unemployment rates soared throughout the state. By the end of the 1970s, the economy had improved but the traumatic effects of the "Boeing Bust" remained in Washington's collective psyche for years to come.

The Jet Age

When the first Boeing 707 entered service in 1958, a new era of air travel began. Although Great Britain and Russia had already built commercial jet airliners (the de Havilland Comet and the Tupelov TU-104) the 707 quickly proved to be the aircraft of choice for most major airlines. The plane quickly became so popular that airports around the world were in a rush to upgrade their facilities and infrastructure to accommodate the new aircraft.

The 707 was a boon to Washington's economy, especially around Seattle, where most people either worked for Boeing or knew someone who did. By the time the plane had entered production in 1957, Boeing's employment had topped 100,000 for the first time in its history. Orders for the new aircraft poured in, and once the 707 became the workhorse for transcontinental and transoceanic travel, airline companies expressed a need for smaller jetliners to serve regional airports with shorter runways.

In 1962, Boeing launched the first 727, a three-engined aircraft that could fly between 2,500 and 3,000 miles. The 727 was another big success for the company, and airlines enjoyed its use not only for passenger service, but for carrying cargo. A stretched version of the plane was launched in 1967 to allow more passengers. That year, Boeing also launched the first 737, designed to fill the gap between 727 and 707 markets.

Jumbo Jet

By the mid-1960s, the Boeing Company was flying high. Between 1965 and 1968, Boeing's payroll had almost doubled and airplane sales were robust. The company had diversified into the space age, first with the Saturn rocket boosters that would help men land on the moon, and later with the Lunar Roving Vehicle that would drive upon its surface. As the aviation firm evolved into an aerospace firm, it set its sights on building one of its most audacious planes yet -- the 747 Jumbo Jet.

Plans for the Boeing 747 were developed in the early 1960s, after Pan American World Airways expressed interest in a plane that was larger than the Boeing 707. In 1966, Pan Am placed an order for 25 jumbo jets, deliverable in three years. Boeing gambled almost everything it had to make this project a success, even though the time frame was short, the design was not yet complete, and a production plant had yet to be built.

To get the job done, Boeing had to change the way it built aircraft. More than 65 percent of the work was subcontracted to other companies and construction began on a new modern assembly building in Everett. By the time the building -- the world's largest under a single roof -- was complete, all the pieces needed to build a jet airliner would be assembled there. The only parts manufactured at the Everett facility were the wings and the forward body sections, including the flight deck. Employment at Boeing was at an all-time high, with 142,000 working directly for the company and thousands more working for suppliers, many of which were based in Washington.

Troubles Begin

In 1968, William M. Allen (1900-1985) -- Boeing's president since 1945, and who had overseen the launches of the 707, 727, and 737 -- stepped down to become chairman of the board, and handed the reins to T. A. Wilson (1921-1999), who had begun work at Boeing in 1943 as an aeronautical engineer. Allen oversaw most of the 747 program, but it was Wilson who guided it through to completion. At the time, the 747 program was one of the largest nongovernmental projects in United States history.

When the 747 was rolled out in September 1968, it was christened by 26 flight attendants, one each from the 26 airlines that had already placed orders. Five months later, the first jumbo jet, christened the City of Everett, had its maiden flight from Paine Field in Everett, and crowds stood in awe as the gigantic plane -- almost twice the size of a 707 -- took to the skies.

The 747 appeared to be another huge success for the company, but behind the scenes executives were getting worried. Development costs of the 747, and also the 737, were higher than expected. Meanwhile the airliner market had become saturated, and while plenty of deliveries were being made, new orders were falling off. Compounding this dismal economic outlook were troubles with another Boeing program -- the supersonic transport (SST).

The Need for Speed

Boeing began studying the feasibility of supersonic transport in the 1950s, but the project found greater support after President Kennedy requested that the Federal Aviation Administration recommend improvements that could be made regarding the nation's civil aviation industry. His newly appointed FAA director Najeeb Halaby (1915-2003) proposed that the government fund design studies for an American SST that could carry up to 175 passengers and reach speeds of Mach 2.5.

Military brass scoffed at the idea, worried that the SST would divert funding from military aviation projects. Other skeptics felt that the SST would be too expensive to build and maintain. But after the United Kingdom, France, and the Soviet Union announced their plans to build SSTs, American aircraft manufacturers all agreed that the United States should not fall behind in the aerospace race. Kennedy introduced the National Supersonic Transport program in 1963.

Boeing proposed a plane that could carry 250 passengers and reach speeds of up to Mach 2.7. The Boeing design also included a swing-wing configuration, in which the wings could be swept back during high-speed flight. Lockheed, Boeing's chief competitor for the contract, favored a fixed delta-wing. In 1966, both companies submitted their proposals with full-scale mock-ups, and Boeing was awarded the contract on New Year's Eve. Inspired by this potential boost to Seattle's economy, the city's new professional basketball team was named the SuperSonics by its owner.

Turbulence

Almost from the start, the SST program suffered through redesigns and delays. The pivot mechanism of the swing-wing added more weight than was planned, and the company reverted to a modified delta-wing design that only had a slight amount of sweepback. Engine placement also had to be changed, and by the final configuration the engines had been moved to the trailing edge of the wings to protect them from shock waves caused by high speeds.

By 1969, the project was already two years behind schedule, and work hadn't even begun on building the prototypes. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union had launched the Tupelov TU-144 a year earlier, making it the first commercial SST in the world. The Concorde, built in a combined effort by the United Kingdom and France, had its maiden flight in March 1969. Later that year, President Nixon announced that it was essential for the U.S. SST program to continue, in order to maintain the nation's leadership in the aviation industry. He requested Congress to appropriate $662 million over a five-year period to keep the program on track.

Meanwhile, the Boeing Company was entering a steep rate of decline. By mid-1969, more than 12,000 workers had left through attrition, and by the end of the year, employment had declined by 20 percent after layoffs began. There was some good news, though. Twenty-six airlines had already placed orders for 122 SSTs. But the drop in employment continued.

Tailspin and Crash

By 1970, the company was in a financial crisis. That year, no new orders came in from any U.S. airline for any type of Boeing aircraft, and only a few foreign airline sales were made. And because the company had already borrowed a billion dollars to finance the 747 program, no creditors could be found to lend it additional funds. The Boeing Company struggled to remain solvent.

Layoffs hit every department. The number of hourly workers declined from 40,000 to 15,000. The number of engineers and scientists, which had been near 15,000, dropped by more than half. Office staff was cut from 24,000 to 9,000. Managerial positions were slashed all the way up the line, and even the top executives took pay cuts of up to 25 percent.

Then, everything went from bad to worse. As SST costs continued to rise, some members of Congress -- most notably Wisconsin Senator William Proxmire (1915-2005) -- had been eyeing the program as unnecessary federal spending. Although there was support from some elected officials, most notably those backed by labor unions, the U.S. Senate rejected an appropriation in December 1970 to continue development of the SST. Three months later, the Senate cut all funding whatsoever, and the project was cancelled.

Turn Out The Lights

By this time, the "Boeing Bust" -- as it was soon to be called -- sent shockwaves throughout the regional economy, mainly due to Seattle's overreliance on Boeing as an employer. In 1970, Seattle's unemployment rate was 10 percent compared to a national average of 4.5 percent. After the cancellation of the SST program, unemployment in Seattle went as high as 13.8 percent. Boeing laid off more workers, and its payroll bottomed out at 38,690 -- far fewer than during peak employment just a few years earlier.

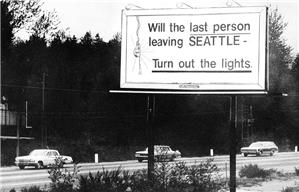

With few jobs to be found, many people decided to move elsewhere. Housing prices fell drastically. Stores and restaurants experienced huge drop-offs in business. The birth rate fell, the suicide rate climbed. To counteract the grim outlook that pervaded to region, real estate agents Bob McDonald and Jim Youngren rented a billboard near Sea-Tac Airport, and posted the humorous message "Will the last person leaving SEATTLE -- Turn out the lights."

Slow Recovery

By 1972, Boeing started hiring again, thanks to military contracts including the Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS), a modified Boeing 707 with a rotating radar dome, used in airborne surveillance. But just as the Seattle area was hoping to crawl out of its hole, a nationwide recession hit in 1973, coupled a worldwide oil crisis. At least everyone was miserable now.

By the latter half of the 1970s, the recession had waned, and Boeing began to soar once more. Plane sales were up, military contracts were coming in, and by the end of the decade, Boeing employed close to 100,000 people again. Most of this success was attributed to the tight-fisted leadership of T. A. Wilson, whom The Associated Press named in 1978 as one of Washington state's 10 most powerful people.

The "Boeing Bust" was traumatic throughout the state, but it had long-lasting positive effects on the greater Seattle metropolitan area. Although Seattle's population dropped to under half a million by 1980 (down from 565,000 in 1965) suburban communities saw their numbers rise -- mostly due to lowered housing prices -- giving them more of a say in decisions that affected regional growth management. Government and business leaders also shifted their focus beyond Seattle, and looked for ways to diversity the economy, so as to become less dependent upon a single employer.