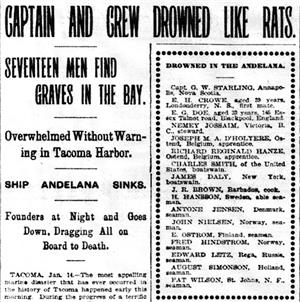

On January 14, 1899, the four-masted bark Andelana is lying at anchor at Tacoma preparatory to taking aboard a large shipment of wheat bound for Europe. During the night, a squall sweeps across Commencement Bay with wind gusts of 40 mph. Without cargo or ballast aboard, the Andelana is decidedly top-heavy and she capsizes and quickly sinks in 200 feet of water. The crew aboard the Andelana is trapped in the berthing quarters and goes down with the ship. The only survivor is an apprentice seaman who is at a Tacoma hospital recovering from a serious injury. All attempts to raise the sunken vessel will prove fruitless, and today the Andelana remains on the bottom of Commencement Bay, the grave of 17 hapless mariners.

The Vanishing

The Andelana was a four-masted, square-rigged bark built by R. Williamson & Son, Workington, England, in 1889 for the Andelana Sailing Ship Company, Ltd., of Liverpool, England. The 2,395 ton, steel-hulled ship was 303.8 feet in length, 42.3 feet abeam with a 24.6-foot draft. The ship's master was George W. Stalling, age 42, from Nova Scotia, an experienced, lifelong mariner, who had sailed the world.

The Andelana arrived in ballast at Tacoma from Shanghai, China, on Monday, January 9, 1899, and, under charter to Eppinger & Company, San Francisco, was scheduled to load a large shipment of wheat for Europe. The vessel was moored at Eureka Dock, 535 Dock Street, a 400-foot, 130-foot wide warehouse facility, operated by the Tacoma Warehouse & Elevator Company, capable of holding up to 10,000 tons of grain. At Eureka Dock, all the ballast was removed from the Andelana and her holds cleaned and hatches left open preparatory to loading 3,500 tons of grain.

When the Andelana arrived in Tacoma, Captain Stalling had a full crew of 28 men including the officers. While in port, eight seamen plus the Second and Third Mates signed off the vessel and signed aboard the cargo vessels SS Dirigo and SS Henry Failing. It was rumored that the Andelana was unstable in heavy seas, due of her unusually tall masts, and those seaman refused to make another voyage aboard her. Replacements were difficult to find, so what remained of the crew was not allowed to go ashore while the ship was in port. However, Percy B. Buck, an apprentice seaman, was permitted to leave the ship for treatment of a serious face injury at Fannie Paddock Memorial Hospital (now Tacoma General Hospital).

On Friday, January 14, 1899, the Tacoma Tug and Barge Company tugboat Fairfield moved the Andelana to an anchorage in the middle of Commencement Bay. After dropping the starboard anchor, weighing three tons, long, thick ballast logs were chained to both sides of her hull to keep the ship on an even keel while she was riding high without ballast or cargo in her holds.

At approximately 2:30 a.m. on January 15, a violent squall swept across Commencement Bay with rain and wind gusts in excess of 40 mph. At daybreak, Captain Samuel Doty of the British four-masted bark Walter H. Wilson, which had been at anchor a few hundred yards from the Andelana, noticed the ship had vanished. Assuming the vessel had slipped her anchor and drifted away during the storm, Captain Doty had his crew launch a dinghy and row him to the Eureka Dock where the tugboat Fairfield was moored.

There, Captain Doty enlisted the help of Captain John E. Kenney, Tacoma's Port Surveyor, and Captain Thomas S. Burley, master of the Fairfield, and together they crossed to the anchorage to investigate the Andelana disappearance, but they found not a trace of the sailing vessel. The Fairfield then crossed to the northeast side of the bay where, one-half mile from Brown's Point, they found a ballast log, with broken chains dangling, that had been secured to the Andelana's port side. Burley and Doty also discovered a lifeboat and a mattress, both bearing the ship's name, as well as several oars washed up onto the beach. The answer was that she had apparently capsized and gone to the bottom of Commencement Bay.

'Like Rats in a Trap'

A further search of the area for bodies and/or more wreckage proved fruitless. The Fairfield returned to the anchorage and, after four hours with grappling irons, located the Andelana lying broadside on the bottom of the bay approximately 500 yards off the end of the St. Paul & Tacoma Lumber Company Wharf. Captain Burley marked her position with a lighted buoy as a potential hazard to anchored vessels. Late that night, a second lifeboat and a foghorn surfaced and were retrieved from the water.

In the judgment of Captains Burley, Kenney and Doty, the squall that swept across Commencement Bay during the night with gale-force winds, struck the Andelana broadside. The ship was heeled sharply to starboard, lifting the port-side ballast log out of the water, and the log's weight broke the mooring chain. Without the additional weight to stabilize the decidedly top-heavy vessel, she capsized, tons of water flooded her open holds, and she sunk like a stone in 200 feet of water. Captain Stalling and 16 sailors had been trapped in their berthing quarters and went down with the ship. The only survivor of the disaster was seaman apprentice Buck, who had been hospitalized the previous day.

After learning of the disaster, George Kennedy, quartermaster aboard the steamship Tacoma, told the Seattle Post-Intelligencer that he had shipped with the Andelana on her last voyage but had signed off the vessel at Shanghai. Kennedy said that he learned from a former shipmate, who had signed off the ship in Tacoma, that Captain Stalling had been locking the crew in the forecastle at night to prevent anyone from deserting and leaving the ship shorthanded. "They must have gone down like rats in a trap without a chance to save themselves," opined Kennedy ("Sailors Were All Locked In"). Replacements had been hired but not due to report aboard until the day of departure.

Deadly Aftermath

The Andelana was insured by Lloyd's Maritime of London for $100,000, and Lloyd's contracted with salvagers to explore the likelihood and cost of raising the vessel, which was believed to be largely undamaged. Among the proposals were dragging the ship into shallow water where divers could safely batten down the hatch covers and pump out the sea water while pumping in air. Once the masts, spars, and rigging were removed, weighing some 40 tons, the ship should theoretically right herself and almost float to the surface. A dry-dock from Quartermaster Harbor would then be moved into position and assist in pulling the Andelana to the surface. The vessel would be refitted at the Dockton shipyards on Maury Island in King County.

Ultimately, all efforts to raise the Andelana failed. Expensive equipment was procured and brought to the wreck site on barges. Numerous grappling irons were affixed to the hull and cables strung to four of the most powerful tugboats on Puget Sound. As the tugboats powered ahead, the cables, unable to withstand the weight, parted. Suddenly relieved of the enormous burden, the tugs surged forward, almost ramming a nearby dock.

Several more attempts were made to raise the vessel, but, due to the water's depth, all were unsuccessful and a few lives were lost. The most notable was William Baldwin, 45, a master mariner and deep-sea diver from Seattle. Hard-hat divers did not usually descend beyond 150 feet because of the terrific water pressure. However, Baldwin made three dives to the Andelana at a depth of 200 feet, which constituted a record for deep-sea diving at the time. Unfortunately for Baldwin, the compressed-air pump aboard the salvage barge was guaranteed only to deliver pressure of 75 PSI (pounds-per-square-inch), and 95 PSI was required to insure the diving suit remained inflated properly at a depth of 200 feet. During his fourth descent, the gasket on the pump's third cylinder failed, the pressurized suit collapsed, and Baldwin was immediately crushed to death. A Pierce County Coroner's jury exonerated Baldwin's dive crew, stating they did everything possible to save his life after the mishap occurred. It was Baldwin himself who had inspected the air compressor the previous day and thought it was safe. He was to receive $35,000 for his daring efforts if the Andelana was raised.

After Baldwin's death, further serious attempts to salvage the vessel were abandoned. There were a few perfunctory plans to move the ship away from the anchorage where she constituted a minor hazard, but none came to fruition. It was finally agreed that the Andelana could not be salvaged and she was left to be covered by tons of silt flowing into the bay from the Puyallup River. To this day, the four-masted bark lies rusting at the bottom of Commencement Bay, the final resting place of 17 hapless mariners.

Victims:

J. R. Brown, cook, Barbados, BVI

E. H. Crow, first mate, age 39, Londonderry, Nova Scotia

James Daly, boatswain mate, 42, New York

Joseph M. A. DeHoeyere, apprentice, 19 Ostend, Belgium

E. G. Doe, second mate, 33, Blackpool, England

Richard Reginald Hange, apprentice, 18, Ostend, Belgium

H. Hansson, able seaman, 31, Sweden

Antone Jensen, seaman, 30, Denmark

Verney Jossaim, steward, 37, Victoria, British Columbia

Edward Letz, seaman, 25, Rega, Russia

Frederick Lindstrom, seaman, 47, Norway

John Nielsen, seaman, 28, Norway

E. Ostrom, seaman, 28, Finland

August Simonson, seaman, 23, Holland

Charles Smith, boatswain mate, 49, USA

George W. Stalling, Captain, 42, Annapolis, Nova Scotia

Patrick Wilson, seaman, 26, St. Johns, Newfoundland