Daylight saving in Washington has a long and contentious history, shaped by conflict between urban and rural interests. Its history is marked by many local referendums and three hotly debated, statewide ballot initiatives, including a ban on daylight saving that passed in 1952 with 60 percent of the vote. Today, the time of day once again may be in flux. In 2019, the Washington Legislature enacted a measure to put the state on daylight saving year-round, if Congress approves the time change.

Rooted in Britain

The earliest attempts to establish daylight time began in Britain with a bill introduced in the House of Commons in 1908. The Daylight Saving Bill would have advanced clocks each April by 80 minutes, but gradually, in four weekly, 20-minute increments, and then set clocks back again in September the same way -- a total of eight time changes a year. This complicated concept drew support from Winston Churchill, Arthur Conan Doyle, and other prominent Britons including one Lord Avebury, who said it "would be a great convenience to merchants and bankers" (Seize the Daylight, 13). The proposal was killed after farmers complained that it would cause them inconvenience, such as by forcing them to wait longer for morning dew to evaporate from their fields.

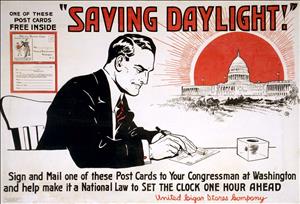

Rural hostility -- and receptivity among city dwellers and business interests -- shaped discussion and policy on daylight saving for the next several decades, particularly in Washington. Many saw the time change as an aid to commerce and industry. But many who worked the land, and lived more by the unalterable cycles of the sun and moon, saw it as a threat. Oddly, many Americans today erroneously think the time change began as a favor to farmers. Actually it began during World War I to save fuel, primarily coal. Germany was first to reset its clocks in the summer of 1916. Britain retaliated by doing the same. The U.S. followed two summers later.

Cities Save

After the Armistice, more genteel warfare broke out between farmers, who sought repeal of daylight saving, and people in towns who had enjoyed later summer sunsets after work in factories and offices. President Woodrow Wilson twice vetoed repeal, which was slipped into agricultural appropriation bills. When Congress voted on whether to override the second veto, Washington House members split their votes, but both of the state's senators, Miles Poindexter and Wesley Jones, voted yea, as did more than two-thirds of both chambers. The time change -- and daylight saving -- went away in 1920.

But not entirely. Nothing then prevented states and even cities from ordering observance of daylight saving within their boundaries. By 1932, about one-quarter of Americans were setting clocks forward in the spring for fast time, as headline writers liked to call it. Washington state held back, but Seattle adopted daylight saving in May 1933, after a campaign by the Seattle Junior Chamber of Commerce, known today as the Seattle Jaycees. Spokane and some other Washington cities also moved clocks forward, encouraged by Seattle or wanting to stay in synch with it.

They regretted the move almost immediately. With unincorporated areas and some cities left behind, the next several weeks were marked by missed trains and inconsistent business and office hours. Ferries on some routes changed time zones as they crossed Puget Sound. In Spokane, schools were on standard time, businesses observed daylight time, and some federal offices observed one time, some another. Parents complained of children refusing to go to bed with the sun still high. Ministers reported a drop in church attendance, not from a crisis of faith, presumably, but because services came sooner after sunrise.

Daylight Dims

Cities soon scurried to return to standard time. Seattle was the last to retreat, in August, a month earlier than planned, amid a general air of disillusion. "The confusion this year was such we doubt whether it will be tried again," declared The Friday Harbor Journal. The Bremerton News agreed: "This is the last time the clock-twisting arrangement will be made" ("What the State Thinks ..."). A referendum to bring daylight saving back the next year in Seattle was overwhelmingly rejected by city voters, per the Seattle Times' recommendation in a front-page editorial:

"The only persons who favor daylight saving are those who hold to the illusion that it gives them more time for outdoor recreation. There are many such persons, to be sure; yet obviously they constitute but a small minority of Seattle's population. Daylight saving is detrimental in nearly every line of industry and business; it is an exasperation in nearly every home, especially where there are children. It requires too much of a sacrifice from too many people, and it should be voted down" ("Right Now!").

Eight years later, daylight saving made a comeback, nationwide, again to save fuel for combat. Soon after Pearl Harbor, Congress declared War Time, ordering clocks moved ahead an hour, beginning on February 9, 1942, for the duration of World War II. Winter daylight saving made for late sunrises in northern latitudes such as Washington. Concerned for the safety of children on their way to school, Seattle's school board twice voted for resolutions urging Congress to roll back War Time during the school year. But most Americans put up with it as another sacrifice needed to defeat the Axis powers.

Two weeks after V-J Day in 1945, a canvass of city residents by a Seattle Daily Times reporter found "Mothers, School Folk and Grocers Want Standard Time," as the headline had it. Congress repealed War Time the next month.

Peace, But Not About Time

State and local daylight-saving schemes were suspended during the war, but peace put the hour up for grabs again. By 1947, about 40 percent of Americans were observing summer daylight saving, in a geographic patchwork and on many different schedules. Iowa, for example, had 23 different combinations of start and end dates for daylight time.

Washington state still shunned daylight saving, and Spokane voters rejected a clock change for the city in a 1947 referendum. But Seattle's city council decided to give it another try beginning on June 1, 1948. This time, things went more smoothly. Most Western Washington towns and unincorporated areas joined in. Schedules for trains, airlines, and inter-city buses stayed on standard time; some passengers arrived at stations and the airport an hour early, but they mostly took that in stride.

The first season was successful enough that most Western Washington cities extended it one month longer than planned, to September 25, 1948, in line with the schedule observed elsewhere in the nation. In November 1948, Seattle voters overwhelmingly approved a referendum to return to daylight saving the next spring and beyond. Other Washington cities followed suit. Seattle voted again in 1950, and again favored daylight saving for the city.

Farmers vs. City Folk

But farmers continued to oppose daylight saving. In 1952, the Washington State Grange, then a powerful advocate for rural communities, put forward a statewide initiative to ban daylight saving unless ordered by the governor in time of war. The Grange argued that local-option daylight saving created a "hodge-podge patchwork" that was confusing and inconvenient:

"Our state's economy is so integrated that it is definitely unsound business for various portions of our population to work on different time schedules. Any practice designed for pleasure, such as daylight-saving time, is unsound when it retards production of wealth or causes inconvenience. In addition, our state's northern latitude gives us the greatest number of summer daylight hours of any state in the Union. It is foolish for us to follow an inconvenient, injurious time pattern originated by southerly states which do not share our summer daylight advantage" ("Important Issues ...").

The Seattle Junior Chamber of Commerce again championed daylight saving and led opposition to the Grange initiative. The Chamber noted that staying on standard time would put Seattle and Tacoma out of step with other Pacific Coast seaports and with major East Coast cities, where daylight saving was by then commonly observed. Among daylight saving's other advantages, according to the Chamber:

"It combats juvenile delinquency by encouraging young people to participate in healthful outdoor activities, enables fathers to enjoy an additional hour of outdoor relaxation with their families sand vast numbers of office, store and industrial workers to get out in the sun while gardening, participating in sports or improving their homes. Medical authorities testify that an extra hour of outdoor relaxation in the evening is much more beneficial to the individual than at the beginning of the day. Surely our farmers are interested enough in the well-being of their fellow citizens to permit them to enjoy wheat the farmer has all day" ("Important Issues ...").

On election day in November 1952, the initiative won 60 percent of the vote, racking up even larger margins in rural areas. In Washington, saving daylight again became illegal.

Statewide Advance

Its defenders were undeterred. They maintained that voters were confused by the Grange initiative, on which a yes vote was a vote against daylight saving. Two years later, in 1954, the Seattle Junior Chamber advanced an initiative to establish statewide daylight saving. Washington voters trounced it, as urban and rural voters again split.

Through the 1950s, however, more states adopted daylight saving, making Washington an outlier. The state grew more urban. And at the influential Seattle Times, the publisher's mantle had been handed down from C. B. Blethen to W. K. Blethen. When the Seattle Junior Chamber came forward in 1960 with another initiative for statewide daylight saving, the Times reversed its earlier opposition, publishing multiple editorials urging citizens to sign petitions and vote yes:

"It may be inspiring to rise and watch the sun come up before going to work, but most of us, surely, would give a low priority to sunrise-watching as a daylight-hour activity. Most persons would prefer to add an extra hour to those daylight hours remaining after work, so as not to have to wait until weekends for golfing, hiking, swimming, lawn-mowing, hammock-lounging or other summertime activities" ("When Daylight ...").

The measure passed with just under 52 percent of the vote. Washington adopted daylight saving. Its regimen was superseded six years later when Congress enacted the Uniform Time Act, mandating a schedule for the time change and eliminating the local option. Time ceased to be a battleground.

In 2019, little controversy surrounded the proposal to make daylight saving year-round in Washington. Introduced in the House by Rep. Marcus Riccelli, a Democrat from Spokane, and in the Senate by Sen. Jim Honeyford, a Republican from Sunnyside, the legislation attracted broad, bipartisan support. It passed the Senate by a vote of 90-6 and the House by a vote of 46-2. Gov. Jay Inslee signed it into law on May 8, 2019. Oregon and five other states passed similar laws, but all were awaiting congressional action. A bill to mandate year-round daylight saving nationwide was introduced in Congress in March 2019 by Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida. Sen. Patty Murray of Washington became a co-sponsor.