On May 29, 1792, Captain George Vancouver creates the name Puget's Sound to honor his lieutenant Peter Puget. Vancouver is on his exploratory ship, the HMS Discovery, anchored off Restoration Point, which he also names. During the previous week, Puget has been exploring the area south of the Discovery's location. In his journey, he explores the farthest reaches of the Sound's inlets and meets the Native people of the region, who know the waterway as whulge, or the salt water. Eventually shortened to Puget Sound, the name begins to appear regularly on maps in the early 1800s.

A Stretch of Salt Water

The earliest known name for what is now Puget Sound is x̌ʷəlč, often pronounced as "whulge." It comes from the Native language of the waterway, Lushootseed, and means a stretch of salt water. In modern terms, it does not refer to a specific geographic area as illustrated on a map. Instead, it's more of a way to designate a relationship to place. In a 1921 article, ethonographer Thomas Talbot Waterman (1885-1936) hypothesized that the Sound never "obtruded itself as a unit into their [Native inhabitants] consciousness" ("The Geographical Names"). He further wrote that "Indeed, it may be stated as a rule that there is a large series of names for small places, with astonishingly few names for the large features of the region" ("The Geographical Names").

In May 1792, British Captain George Vancouver (1757-1798) arrived in the whulge. He had been sent to this region by the British Admiralty to negotiate a territorial dispute between Spain and Britain. At issue was Nootka Sound, a harbor on the west side of what had previously been thought to be the mainland but which turned out to be an island, after Spanish explorers circumnavigated it in 1792. Both the Spanish, who had visited it in 1774, and the British, who first landed there in 1778, claimed ownership of Nootka, despite the presence of the Indigenous residents who had inhabited the surrounding land for thousands of years. Vancouver's task was to settle the issue, which he did with Spanish representative Juan Francisco de la Bodege y Quadra (1743-1794). To honor the deal, the newly "discovered" island was named Quadra and Vancouver Island, later shortened to Vancouver Island.

At the time, Vancouver was 34 years old and had been part of the Royal Navy since he was 13. During his service with the Navy he had sailed with James Cook (1728-1779) on his second and third voyages of exploration. Previous shipmates included Peter Puget (1765-1822), Joseph Baker (1767-1817), Joseph Whidbey (1757-1833), and James Vashon (1742-1827), who would also join Vancouver on his 1791-1792 expedition.

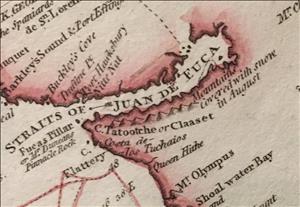

Vancouver had left England on April 1, 1791, sailed south along the west coast of Africa and around the Cape of Good Hope, then east to Australia, north to Hawaii, and across the Pacific Ocean to California. His ship was the sloop-of-war HMS Discovery. It had three masts, carried 125 men, and was 96 feet long. Accompanying him was the 80-foot, armed tender HMS Chatham, captained by William Broughton (1762-1821). More than a year after leaving England, the two ships entered the Strait of Juan de Fuca on April 30, 1792.

Although resolution of the Nootka situation was his main goal, Vancouver also had orders to seek out the so-called Northwest Passage, the mythic shortcut linking the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. Therefore, he directed the Discovery and Chatham into the Strait to see how far east it extended. On May 19, Vancouver turned his boat south into what Puget described as the great SE Inlet. It was an area the crews had previously ventured just far enough into to explore and name a side channel, Hood's Canal, in honor of Viscount Samuel Hood (1724-1816), one of the co-signers of the Admiralty's directive to Vancouver.

Vancouver Sails South

Vancouver sailed south and anchored off an unnamed island, now known as Bainbridge Island, at what he christened Restoration Point, "celebrating that memorable event," the restoration of Charles II to the British Monarchy in 1660 ("Vancouver's Discovery"). The Lushootseed name for the point translates to "place of squeaking," in reference to how windy it is, though there was no name for the island itself.

During their short stay at the place of squeaking, Vancouver thought that between 80 and 100 people lived there. He described their lodging as "constructed something after the fashion of a soldier's tent ..." ("Vancouver's Discovery"). This was most likely a seasonal site, used primarily for harvesting what expedition naturalist Archibald Menzies (1754-1842) described as a "little bulbous root of a liliaceous plant," which he described as new to science ("Menzies' Journal"). Originally named Hookera coronaria, it is now known as Brodiaea coronaria, or harvest brodiaea.

Later visitors to Puget Sound described more permanent villages, which were inhabited in the winter. Each consisted of one or more longhouses made of cedar planks, logs, and shingles. The residences varied in size, with the biggest up to 90 feet long, and housed up to 40 individuals of an extended family. Historian David Buerge estimates that several thousand people lived around what is now Seattle at the time Vancouver arrived.

Vancouver also noted something highly unusual about the people on the point, although he had no way of fully realizing what he was seeing. "The dogs belonging to this tribe of Indians were numerous, and much resembled those of Pomerania ... with very fine long hair, capable of being spun into yarn" ("Vancouver's Discovery"). Archaeologist Dale Croes has written that these yarn-bearing dogs are one of only two examples of Indigenous people on the North American continent who "domesticated an animal for its hair for spinning wool to make their textiles" ("The Salish Sea"). The wool was used for blankets, which Croes describes as a central "currency" for trade ("The Salish Sea").

Puget, Whidbey Explore Further

Realizing that smaller boats might be better for further exploration, Vancouver placed Peter Puget in charge of the Discovery's launch and Joseph Whidbey in command of the cutter. The launch was 20 feet long, equipped with two removable masts, and powered by 10 oarsmen; the cutter, slightly smaller. Their provisions included guns, food, and surveying and navigational equipment, as well as trade items such as beads, medals, and trinkets. Menzies, who achieved his greatest fame as the first scientist to describe Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), also joined Whidbey and Puget.

Puget had been at sea since the age of 12. By the time he joined Vancouver, he had sailed in the North Seas, the West Indies, and the East Indies. Puget remained a naval officer for the rest of his life, becoming a captain and eventually a Rear Admiral, in 1821, the year before he died in Bath, England.

Before sunrise on May 20, 1792, Puget and Whidbey and their men left the Discovery. During the week in which they explored the waters south of Restoration Point, they met and traded with the Native residents and surveyed to the Sound's farthest reaches, reaching what are now Budd, Carr, Case, Eld, Hammersly, and Totten Inlets. Puget described the weather as "extremely sultry" ("The Vancouver Expedition"); listed the clothing as "Bear Raccoon Rabit and Deer" ("The Vancouver Expedition"); and considered the flowers "by no Means unpleasant to the Eye" ("The Vancouver Expedition").

When the explorers returned late in the night of May 26 to the Discovery, they found that Vancouver had departed two days earlier in the Discovery's yawl (a 26-foot, three-masted, eight-oared vessel) for further exploration. After Vancouver returned to the Discovery on May 29, spoke with Puget, and learned of the thoroughness of his efforts, Vancouver wrote in his journal: "to commemorate Mr. Puget's exertions, the south extremity of it I named Puget's Sound" ("Vancouver's Discovery").

Defining Puget Sound

Vancouver's original designation of his lieutenant's geographical namesake referred only to the region south of the Tacoma Narrows; all the water north to what Vancouver called Point Wilson received the name Admiralty Inlet. By the 1830s, Puget's Sound had "grown" to include Admiralty Inlet, and by the 1850s, a pre-Civil War lieutenant George B. McClellan (1826-1885) would define the Sound as a "sheet of water" north to Bellingham Bay ("Origin of Washington"). Not content with that limited terrain claim, another military officer, Brigadier General William S. Harney (1800-1889), wrote in 1859 that the "island of Vancouver [is] in Puget's Sound" ("Origin of Washington," 235). In 1866, the Territorial Legislature (Washington didn't become a state until 1889) wrote a memorial claiming San Juan Island as "situated in the waters of Puget Sound."

Over the subsequent century the geographic boundary of Puget Sound continued to be protean, expanding and contracting depending on political expediency. In 1987, the state of Washington made permanent the biggest expansion when the Puget Sound Water Quality Authority defined Puget Sound as "Puget Sound south of Admiralty Inlet (including Hood Canal and Saratoga Passage); the waters north to the Canadian border, including portions of the Strait of Georgia, the Strait of Juan de Fuca south of the Canadian border, extending westward to Cape Flattery; and all the land draining into these waters" ("Puget Sound Water").

One way to think of these definitions is as Greater Puget Sound, the larger boundary as defined by the state, and Puget Sound Proper, the waterway south of Admiralty Inlet.