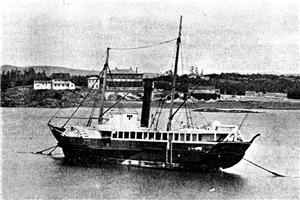

On November 12, 1836, the steamship Beaver arrives at Fort Nisqually, making it the first steamer on Puget Sound. The Beaver's docking culminates a voyage that began in London, where the Beaver was built and initially outfitted as a brigantine. The voyage continued as the Beaver sailed across the Atlantic, around the Cape of Good Horn, up to Hawaii, and across the Pacific. Powered by 13-foot-diameter paddlewheels, the Beaver will ply the waters of Puget Sound for decades to come before ultimately crashing into shore, on July 25, 1888, at Calamity Point in Burrard Inlet (now Prospect Point in Stanley Park, Vancouver, British Columbia).

Built on the Thames

No one knows what the first boats were on Puget Sound. Long since decomposed, they could have been made of wood, hide, or bark. The most likely choice was some kind of canoe made of wood, though the preferred building material of the earliest exant canoes -- western red cedar -- did not become prevalent locally until about 5,000 years ago. But once cedar forests began to spread, the wood became the lone source for canoes.

Eventually, the Indigenous residents developed superb craft adapted to the specific conditions of Puget Sound. The primary canoe was the Coast Salish style, which came in two varieties, each with an angled bow and stern. The heavier design was for hauling freight and could be equipped with a sail made of cedar bark or cattail. In contrast, the more mobile troller was used for fishing, hunting fowl, and harpooning marine mammals. Those who lived upriver developed their own style, a shovel-nose canoe with a squared bow and stern. They could be paddled or poled with a person standing in the front to hunt fish in rivers.

This world of human-powered, and later wind-powered ships, began to change on November 12, 1836, with the arrival of the Beaver. Work on her had begun in June 1834, on the Thames River in London. The owner would be Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), which had two forts in what would become Washington: Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River and Fort Nisqually at Steilacoom. Made with African teal planking; an elm keel; and oak stem, stern-post, and ribs, or internal framing, she was further protected by tar paper and additional planking made of fir. A final sheathing of copper was used to block teredo worms, the notorious wood-boring clams that can Swiss cheese a boat in weeks. Powered by paddlewheels mounted a bit forward of midship, the Beaver was launched into the Thames on May 2, 1835.

From Brigatine to Steamship

On August 29, 1835, she headed to North America, though not under power of the paddlewheels. She had instead been retrofitted for the journey as a twin-masted sailing ship, or brigantine. The Beaver was 100 feet 9 inches long and 20 feet wide with draft of 8.5 feet when fully loaded. Across the Atlantic, she reached the Falkland Islands on November 11, 1835, rounded the Cape of Good Horn a week later, and sighted Hawaii -- or the Sandwich Islands as British explorer James Cook (1728-1779) called them -- on February 1, 1836. Two months later, on April 10, the Beaver arrived at HBC's Fort Vancouver, about 100 miles up the Columbia River from its mouth, where crews converted her back to a steamship by reassembling the engine, boilers, and paddlewheels. These could rotate 30 times a minute and speed the Beaver along at a bit under 10 miles per hour.

With this conversion the Beaver became the first steamer in the northern Pacific Ocean. She is sometimes listed as the first steamer in the Pacific Ocean, but she was predated by the Rising Star (1822) and Telica (1825), which operated in South America; the Forbes (1830) and King-fa (1832) in China; and the Sophia Jane, Surprise, and William the Fourth in Sydney, Australia, in 1831.

Following the conversion, the Beaver ran along the Columbia to test her engines. On June 14, the Reverend Samuel Parker (1779-1866), a Presbyterian missionary, wrote: "The novelty of a steamship on the Columbia awakened a train of prospective reflections upon the probable changes which would take place in these remote regions, in a very few years" ("Advent of the Beaver").

The need for a steamship in this remote part of the world had been recognized four years earlier. In August 1832, George Simpson (1792-1860), governor of the HBC in North America, had requested a steam vessel from London. He wrote that it would "afford us incalculable advantage over the Americans, as we could look into every creek and cove while, they were confined to a harbour by head winds and calms." Possessing such a ship, he added, would make us "masters of the trade" ("Advent of the Beaver").

Curiously, HBC's factor (the man in charge) at Fort Vancouver, John McLoughlin (1784-1857), thought that a steamboat "is not required and that the expense incurred on her ... is so much money thrown away" (Letter of September 30). He even queried London asking that if the boat did not perform as expected, did he still have to keep it or could he send it home or sell it?

North to Puget Sound and Beyond

Determined to get the Beaver out of his way, McLoughlin sent her north on June 18, 1836, to various HBC forts, carrying 31 men, which included 13 woodcutters and four stokers. She ultimately reached Fort Tongass, near Ketchikan, Alaska, before returning south, ending up at Fort Nisqually on November 12. In the Journal of Occurrences, the daily log of what happened at the Fort, the entry reads: "Saturday 12: This morning we were greatly surprised with the arrival for the Steamer BEAVER, Capt. Home on board of her, Mr. Finlayson, his Uncle, paid him a visit and got instructions to prepare men for Vancouver. This vessel is from Mill Bank Sound, and has been much detained by the fogs in coming hither. Fair weather" (Journal of Occurrences).

For the next 15-plus years in Puget Sound, the Beaver would serve as a floating HBC trading post, traveling up and down the waterway, and into the Strait of Juan de Fuca, the Strait of Georgia, and even up to Alaska, carrying goods and people. She had one significant limitation: wood. She could store about 40 cords (a cord of wood is a stack 4 feet high by 8 feet long by 2 feet wide), which took six axmen two days to cut wood for 12 to 14 hours of travel, or about 230 miles.

On a voyage in 1841-1842, HBC governor Simpson wrote: "We were detained the whole of the next day by the same indispensable business of supplying the steamer with fuel. In fact, as the vessel carries only one day's stock, about forty cords, and takes about the same time to cut the wood as to burn it, she is at least as much at anchor as she is under way… Still, on the whole, the paddle is far preferable to canvas in these inland waters, which extend from Puget Sound to Cross Sound, by reason of the strengths of the currents, the variableness of the winds, the narrowness of the channels and the intricacy and ruggedness of the line of coast" (Narrative).

Later in her life, after a conversion to coal, the "little black steamer" could travel for several days without seeking out fuel to fire the boilers. The Beaver burned about a ton of coal a day and ran about six to seven knots.

Calamity at Calamity Point

Like many subsequent steamships on Puget Sound, the Beaver served many purposes. During the 1858 gold rush on the Fraser River, she became a passenger ship, ferrying would-be miners from Victoria to the mouth of the river. A year later, she took British military men to the San Juan Islands during the Pig War. Hoping to improve her lot, her owners then added staterooms in 1860, but her days of glory were past, as numerous faster and bigger steamers had arrived, making up what became Puget Sound's famous mosquito fleet. By the mid 1880s, the Beaver had been a towboat, general freighter, and British Navy survey vessel. Her final voyage ended on July 25, 1888, at Calamity Point in Burrard Inlet (now Prospect Point in Vancouver's Stanley Park).

Stuck upon the rocks, she became a popular attraction and site for souvenir seekers, who continued to strip anything they could reach, even after the wake from the large steamer Yosemite further wrecked the Beaver in 1892. The Vancouver Maritime Museum contains a variety of artifacts from the Beaver, including a galley bell, sheathing, anchor, davit, rudder, and wheel.