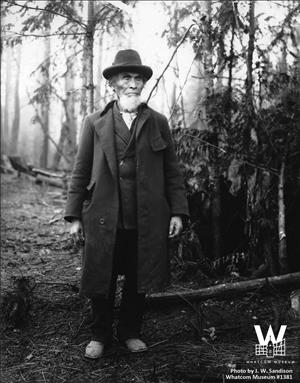

Yelkanum Seclamatan was a Nooksack chief who lived in the Lynden area for much of the nineteenth century and a small part of the twentieth. Though he was not the most dominant chief among the tribe, his influence was felt far and wide with both his fellow Nooksack and with non-Native explorers and settlers. Early Whatcom County settlers knew him as "Indian Jim," but he later became remembered as "Lynden Jim." In order to provide a fuller picture of how Seclamatan lived in the years before and during the early years of non-Native settlement, this essay also discusses Native customs and settlements that existed in northern Whatcom County during the nineteenth century.

Beginnings

Seclamatan's mother is said to have been a "high-born," the Nooksack term for upper class, and he inherited this status from her. He had a sister, Nina, and he likely had other siblings. The year of his birth is debatable. When prominent Lynden citizen Charles E. Cline (1858-1914) wrote the chief's obituary in 1911, he opined that Seclamatan was "nearing his hundredth year" ("Chief Jim ..."), and other sources also say he was born in 1811. But this seems to be part of the lore. Records from when Seclamatan was alive indicate that he was born as late as 1828; for example, his 1903 wedding record says he was 75 years old.

Though we know little of Seclamatan's early years, we have a good idea of how he lived, thanks to the work of a number of Whatcom County authors. This includes Allan Richardson and Brent Galloway, who painstakingly researched the history of Nooksack culture, language, and settlements in Whatcom County for nearly four decades before publishing their work, Nooksack Place Names, in 2011.

Since time immemorial, the Nooksack have inhabited northern Whatcom County and small bits of southern British Columbia. There has been some speculation that at one time their traditional territory extended farther north into British Columbia, beyond the Fraser River, based on similarities of language and housing styles of the Native peoples there with the Nooksack in Whatcom County, as well as evidence of major Nooksack trails to the Fraser River. However, the Nooksack say they have never lived anywhere else.

The name Nooksack comes from the Lhéchelesem word Nuxwsá7aq, and translates into English as "always bracken fern roots." The tribe is one of many Northwest tribes that are part of the Coast Salish cultural group, inhabitants of the coastal regions of the Salish Sea, which includes the northwestern part of Washington and the southwestern part of British Columbia. The Nooksack language is called Lhéchelesem, and while there is evidence that this language at one time extended farther north into British Columbia, by Seclamatan's time it was spoken almost exclusively by the Nooksack living in Whatcom County.

The Nooksack in the Nineteenth Century

By 1820 -- shortly before Seclamatan's birth or possibly during the early years of his childhood -- the Nooksack and other area Natives had endured at least a half a century of population declines brought on in part by exposure to smallpox and other epidemics from the first non-Native fur trappers who passed through the area in the late eighteenth century. One estimate puts the Nooksack population at 863 in 1820, but it kept declining during Seclamatan's youth and early adulthood. In 1857, as non-Native settlement began to encroach on Nooksack lands, the Nooksack population was estimated to be 450. This decline continued through Seclamatan's life, with the Nooksack population reduced to around 200 in the early 1900s before rebuilding their population later in the twentieth century.

Nevertheless, the tribe was still a commanding presence in Whatcom County during Seclamatan's youth. Its territory stretched from just south of modern-day Bellingham north to near the Fraser River in southern British Columbia, where it turned and ran in an irregular line southeast, crossing the international boundary near Sumas and continuing until it reached the crest of the Cascade Range, where it turned south and ran past Mount Baker and dipped into Skagit County before it turned back west toward Bellingham Bay. The Nooksack shared the margins of its territory with other tribes, but other parts of its territory were strictly controlled by the Nooksack. For example, the Nooksack River was the exclusive domain of the Nooksack until its last few miles before Bellingham Bay, where it entered Lummi territory.

In the early nineteenth century the Nooksack lived in at least 13 winter villages on or near the Nooksack River and its tributaries, as well as the Sumas River and Lake Whatcom. Four of these villages on the stretch of the Nooksack River between today's communities of Lynden and Deming were particularly significant: Nuxw7íyem, a large, traditional village at the mouth of the South Fork Nooksack River near Deming; Spálhxen, located about a mile northeast of Goshen; Kwánech, located where Everson is today; and Chmóqwem, which later became the western part of downtown Lynden. At least three of the villages had their own chiefs, but these chiefs were not equal in stature to each other. Though Seclamatan was the chief of the territory surrounding Lynden, he was not the most influential chief of the Nooksack along the river. Jeffcott, as well as Richardson and Galloway, suggest that the most revered chief was Xemtl'ílem, who made his home in the big village at the mouth of the South Fork Nooksack River.

The Nooksack in Whatcom County had distinct customs based on where they lived. Those living near the river and in the valley lived in cedar-plank longhouses similar to those of other Coast Salish groups. Some were small and housed only a single family, but some were quite large and were divided into apartments for families. One longhouse near Goshen was found to be 100 feet long by 30 feet wide when it was inspected by Whatcom County historian Percival Jeffcott (1876-1969) in the 1940s, and it was said by the Native people to have once been 500 feet in length. Longhouses also served as smokehouses and as meeting places for councils and potlatches.

Just north of the Nooksack River at Lynden the land rises a few dozen feet from the valley below, and here many of the Nooksack lived in small conical pit houses. (This type of house would have been impractical in the valley or near the river, as it would have been prone to flooding.) A hole, anywhere from 4 to 12 feet deep, was dug in the ground with poles placed above it with cedar or fir bark acting as roofing material. The walls of the pit had cedar-plank boards covered with reed mats that served as beds. These conical pit houses were unusual for the Lynden area, as they were more commonly found farther north and east of Lynden.

Despite their proximity to the sea, the Nooksack lived primarily off the land and the rivers. They gathered berries, fern, camas roots, wild onions, and they later grew potatoes. They hunted elk, deer, beaver, black bear, and ducks. Though they traveled to Bellingham and Birch bays to gather clams, their main aquatic staple was fish, especially salmon. In his book, Skqee Mus or Pioneer Days on the Nooksack, Emmett Hawley (1862-1946) describes one fish-gathering operation the Nooksack set up on Fishtrap Creek (known to the Nooksack as Xwkw'elám) about 400 yards above where Lynden's City Park is located today. He explains how they built a permanent, fence-like structure across the creek, which routed the fish into a large chute at the bottom with its lower end out of the water. He adds, "During a heavy run I have seen two men standing in the chute, throwing out fish for hours at a time ..." (Hawley, p. 43).

The site was an important one for Seclamatan and for the Nooksack in the area. Hawley says that the chief told him that his father had built the fish trap and that he believed there had been a fish trap there before that. Hawley further writes that in the late nineteenth century there was a roughly 40-foot-square smokehouse near the trap where families lived during the fishing season, and Richardson and Galloway add that many pit house sites have been identified on the north bank of the creek west of the park, near the trap itself. The Nooksack continued using the trap until the end of the nineteenth century.

In addition to the village of Chmóqwem, there were two other Native villages in the Lynden area: Lhchálos, located in what is presently the eastern part of Lynden, near Front Street east of Nooksack Avenue, and Sqwehálich, a village on the south bank of the Nooksack River across from Lynden. As was the case with most Coast Salish tribes, the Nooksack had a social structure of upper class, middle class, and slaves, and one Nooksack elder has said that Chmóqwem was the home of the upper class, while Lhchálos was the home of the Nooksack middle class. Richardson and Galloway write that Sqwehálich appears to have been a less significant village until after 1860, when non-Native settlers began moving into Lynden along Front Street and the two other nearby villages were abandoned.

Seclamatan

Seclamatan owned land at Sqwehálich, which in the nineteenth century was located on the south bank of the Nooksack River. (This site became Stickney Island in 1906, after farmers dug a shortcut through a loop in the river. As a result, the chief's property wound up on the north side of the river.) As non-Native settlement began to slowly increase, he filed for the first Nooksack homestead in 1874. He was granted nearly 160 acres, and though he had to renounce his tribal ties in order to obtain title, he helped pave the way for other Nooksack to file similar claims. He maintained a traditional longhouse at the site for years, which he later replaced with a cabin. The site is located just east of Hannegan Road, north of the Hannegan Road Bridge, near Lynden.

He was known to the Whatcom County's earliest settlers from the start. He moved supplies for the American boundary survey crew during the survey marking the boundary between the United States and British North America (later Canada) in the late 1850s; he helped move Lynden's earliest settlers, Holden (1826-1899) and Phoebe (1831-1926) Judson, to the nascent community in 1870; two years later he helped move the Enoch Hawley family there. (The chief left such an impression on the Hawley's son Emmett that more than 70 years later, Emmett Hawley dedicated his book to him.) He recognized early that it would be to his advantage to work with the settlers, but he remained a strong presence in the fading Nooksack community, regularly taking in children and others who needed help.

He had at least two sons who survived into adulthood, identified in cemetery records as George Thomas Yellowkanim (1846-1905), and Tenas George (d. 1906). He was married at least four times, but the marriage which is most remembered is his brief marriage to Clara Tennant (?-1903). Clara was a Lummi, and the daughter of a tribal leader on the Lummi Peninsula. In 1859 she married John Tennant (1829-1893), one of Ferndale's earliest settlers. Tennant was known for a wealth of accomplishments during his life, but both John and Clara Tennant are remembered for their years-long missionary work with the Nooksack. Clara became a de facto Methodist leader among them, and both she and her husband were involved in the formation of the Stickney Indian School.

In 1884 the Methodists had established a school for Native youth just above a settlement known as The Crossing (near Everson), and in 1890 they decided to move it to Lynden. Seclamatan donated 25 acres of his property and helped raise the requisite funding to build a school building, which opened in 1892 as the Stickney Home Indian Industrial School (often called the Stickney Indian School). The school offered agricultural classes for boys, sewing and other homemaking subjects for girls, and traditional subjects such as English and math for both. Jeffcott writes that attendance at the school peaked at 28 in 1895, but a 1921 Lynden Tribune article says that during the winter months the school had as many as 50 students. The school was open until 1909, and the building was demolished in 1921.

A Humorous Spendthrift

Paul Fetzer (1923-1952), an anthropology student at the University of Washington, interviewed several Nooksack elders in 1950 and 1951 who had known Seclamatan. One elder, Agnes James (ca. 1873-?), describes two potlatches held by the old chief in his later years. One, which was held between 1906 and 1910, was a large affair called by Seclamatan to pay off the funeral debts of his son, Tenas George. A longhouse was built especially for the event (it was built to resemble a barn so it could be used as such afterward), and James recounts that nearly 200 Natives attended, not just Nooksack but also Lummi and Swinomish and, from the Canadian side of the international boundary, Chilliwack and Matsqui.

The event lasted either two nights or three, with the potlatch held on the final night. This was a formal ceremony in which Seclamatan paid off each individual present who had helped with the funeral, as well as each of those who had helped with the potlatch. Leftover funds were distributed to every adult male present, while the women received cloth and dishes; Fetzer writes that this was done as "expressions of grievance for the departed" (Fetzer, 48).

Fetzer interviewed another contemporary of Seclamatan's, Lottie Tom (ca. 1869-?). Tom describes the chief as a "spend thrift" (Fetzer, 59) and says he particularly enjoyed his status as chief. Emmett Hawley describes him as a man who was always there for the settlers, and one who "often enjoyed a joke at the expense of his white friends" (Hawley, 45). Charles Cline describes him in his 1911 obituary as of "a deeply religious nature and early in his life came to believe in the God of the white man and to oppose the pagan practices of some of his people" ("Chief Jim ..."). Though Seclamatan was an early convert to the Methodist faith, one suspects that the chief either feigned opposition to traditional Nooksack practices to please his white neighbors, or Cline simply wrote it on his own initiative.

Lynden Jim Cemetery

Seclamatan died at his granddaughter's home in Lynden on April 25, 1911. Had he died 40 or 50 years earlier, his body might have been disposed of in the traditional Nooksack way. When a chief died his body would be placed in a canoe, or sometimes a split-cedar coffin, with his gun, bow and arrow, and any other valuables. The canoe would be hung high in a tree and secured with cedar branches or other suitable branches. But by 1911 this tradition was long gone, and Seclamatan was buried just west of Northwood Road (about a third of a mile south of Badger Road) in a cemetery that bears his nickname: Lynden Jim Cemetery.

The land for the cemetery came from a tract of land donated by "Indian Joe" (Hawley, 187), a Native who is not otherwise identified. It was donated specifically to serve as a Native cemetery, and records show that it was in use by 1885. Seclamatan, his son Tenas George, and others shared expenses in building the cemetery, and they and other family members are buried there. The original cemetery was divided in two when Northwood Road was built in the twentieth century, and in 2020, these two cemeteries are Jobe Cemetery, on the east side of Northwood Road, and Lynden Jim Cemetery on the west. Though the Jobe site is well-maintained, the Lynden Jim site has not been maintained in decades and is completely overgrown.

Seclamatan's old friend Charles Cline finished the chief's obituary with a goodbye written in the Chinook jargon. It reads as follows:

"Nesika tillakum; kloshe mika moosum. Hyas klahowya, pe alki nika nanitch mika" ("Chief Jim ...").

Tillakum is the Chinook word for friend, a fitting tribute to a man who was fondly remembered by nearly all his contemporaries, and whose name lives on today: In 2017, the City of Lynden named a new city park "Northwood Lynden Jim Park" in his honor.