On March 6, 1874, Joe Nuanna (1856-1874) is hanged at Port Townsend for the brutal murders of Harry (ca. 1839-1873) and Selena (ca. 1850-1873) Dwyer, young homesteaders on San Juan Island. When the victims were discovered in May 1873, island sheriff Stephen Boyce (1829-1909) investigated and Nuanna, commonly known as "Kanaka Joe," became a suspect. When he fled to Victoria, British Columbia, Boyce followed and, with the cooperation of the Victoria police, apprehended him. Nuanna is extradited to the U.S. for a trial that takes place in Port Townsend. With strong evidence provided by Boyce, he is found guilty and sentenced to hang the following March, and subsequently confesses to a third murder on San Juan Island. A large crowd attends the hanging, which becomes a ghastly spectacle when the prisoner, instead of experiencing a quick demise, dies a slow and harrowing death.

San Juan Islanders and an Unsolved Murder Mystery

Until 1872, San Juan Island, part of the sparsely populated San Juan archipelago in the Salish Sea between Vancouver Island and the Washington mainland, had been jointly claimed and occupied by both Britain and the United States. Even after the boundary dispute was resolved in favor of the U.S. that October, both British and American settlers continued to live on the island, whose open prairies, ample timber, abundant fish supply, and good harbors were an attractive draw. William Fuller (referred to in some sources as Samuel Fuller), a bachelor Englishman and carpenter, had taken a full claim on which he ran only a few sheep and did not actively farm. A neighbor, who remembered Fuller as a proud man, was fascinated as a child by his appearance, because in a time of full mustaches and flowing beards, Fuller shaved his face except for the area from his ears to the back of his chin where he kept his beard trimmed to a neat two inches. He was always smartly dressed and wore a stovepipe hat when he attended important events, all signs of a life of comfortable independent means.

In late 1872 a neighbor came to visit Fuller but found a puzzling scene. The door to his house was standing wide open, Fuller was nowhere around, and his dog Jinny seemed agitated and anxious. The neighbor returned home but was disturbed about what he had seen and went back the next day only to find everything just as before. Now thoroughly alarmed, he reported the strange facts to the neighbors and went to fetch Stephen Boyce, the sheriff appointed by the commander of the American military garrison on the island, then still in charge of local island affairs for the American settlers.

A search was begun immediately, but it was several days before Fuller's body was found, with Jinny's aid, buried under heavy rocks at the base of a madrona tree in a thicket on his property. He had been shot through the head and then battered with a stone before being buried under the camouflaging rocks. A careful investigation revealed no clues to the identity of the murderer or motive, although some settlers thought he might have been killed because of some dispute with Haida Tribe members from the north who were known to occasionally attack homesteaders on the island. Neighbors made a coffin and buried Fuller in a grove of trees on his land, but the mystery of the murder remained unsolved.

The Murders of Harry and Selena Dwyer

The following year, two more murders caused even more distress in the island community. Harry Dwyer had immigrated from Nova Scotia and developed a successful business shipping goods between Victoria on Vancouver Island and San Juan Island just across Haro Strait. With U.S. sovereignty undisputed, Dwyer anticipated that the flow of goods between Victoria and San Juan Island would diminish, and he decided to sell his sloop and take up farming. Harry brought to San Juan Island his 20-year-old bride, Selena, whom he had met and married in Victoria. (Dwyer had been married to a Haida woman on the island but had turned her out when he fell in love with Selena). In spring 1873 Harry and Selena were settling into their homestead on the west side of the island at the foot of a mountain with heavy timber on its flank, a wetland area, and a meadow for farming. The house, barn, and outbuildings stood on a knoll with a lovely view from the porch where Selena could sit and sew for the baby she was expecting. The ground had just dried enough to plow, and Harry was anxious to prepare his fields.

One May morning a neighbor stopped by and spotted Harry lying on the ground next to his plow, the horses were still standing in harness. When the visitor approached, she could see that they had scuffed a deep depression trying to get away. Harry had been shot through the head and fallen with the reins wrapped around and under his body. He had been lying there for some time. Horrified, the neighbor ran to the house and found an even more gruesome scene: baby clothes scattered about and Selena, shot and with her head beaten, in a pool of blood in the kitchen. A wooden box in one room stood open, empty; it was determined later that papers, money, and watches were missing.

Stephen Boyce was summoned immediately. Minerva Hannah (1844-?), who lived on the adjacent homestead and with whom Selena Dwyer had stayed for a few days when she first arrived on the island, had been alerted to the tragedy and went over to see if there was anything she could do for Selena but left immediately when she saw the ghastly scene. It was to haunt her for days, and she kept mulling over the question of who could have done it and who would have known that there would be money in the house.

The Dwyers were British citizens and, when word of the murders reached Victoria, British Crown Colony Governor James Douglas (1803-1877) sent a special officer to aid the investigation. Victoria newspaper the British Daily Colonist declared that the Dwyers were "so intimately identified with this community that they were regarded as part and parcel of it" ("Fish and Flesh"). When the Dwyers were taken to Victoria for burial, many hundreds of local citizens viewed the bodies and the paper noted that few came away with dry eyes. The Victoria chapter of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows fraternal organization offered a $500 reward for the arrest and conviction of the guilty party.

The Investigation

Meanwhile, on San Juan Island, Boyce was undertaking a careful investigation, beginning with a thorough check of the Dwyer home and outbuildings. In the house he found the open, empty box in which the Dwyers were known to keep valuables, and on the roof of the root cellar he discovered a small pouch of shot, but mentioned this to no one. The Puget Sound Dispatch, like other regional newspapers, was picking up news from the Daily Colonist, which was closely following and reporting on the investigation. The Dispatch announced that "the perpetrator is believed to be a white man, as the tracks of No. 7 boots, full-nailed, are plainly traced through the field along with Dwyer's tracks" ("The Shocking Murder ...").

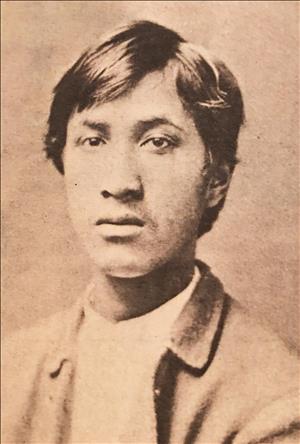

Lila Hannah (later Firth) (1865-1954), Minerva Hannah's young daughter, noticed that her mother seemed preoccupied and asked why. Hannah explained she was still thinking about who could have been the murderer. She remembered that 17-year-old "Kanaka Joe" Nuanna had come to the house a few days before and asked if he could borrow a shotgun to shoot some pigeons. Joe was a familiar presence on the island. Of mixed Hawaiian and Native American parentage, he lived at Kanaka Bay, an area on the southwest shore of the island populated by many of the Hawaiian laborers, known locally as Kanakas, who had been brought to the island by the Hudson's Bay Company to act as shepherds and work in the fields, becoming part of the small island community.

Minerva Hannah had loaned Nuanna the gun and some shot without concern and, when he returned the gun, she put it away and gave it no more thought. But her daughter Lila recalled that when he brought the gun back he had acted strangely, not coming to the house as usual, but instead pacing about near the farm's pond until her mother had sent her out to talk to him. When Lila approached, he shoved the gun into her hands and immediately bolted away; she had noticed that he wasn't carrying any pigeons or game. This discussion prompted Hannah to take the gun out again to good light and, inspecting it more closely, she found blood on the gun stock. Sheriff Boyce was notified immediately and closely questioned the Hannahs.

Boyce next paid a quiet call at the village on Kanaka Bay but was told that Nuanna and a friend known as Indian Charlie had left for Victoria. Boyce soon followed, as did Edward Warbass (1825-1906), San Juan Island justice of the peace, and later Charles McKay (1828-1918) and others, who had also known both Joe Nuanna and the Dwyers.

The Victoria police took the lead in the investigation and, acting in part on information from Boyce and Warbass, soon took several suspects into custody. Nuanna was found casually walking down Fort Street. The prisoners were charged with murder and brought into police court for the first of several hearings that large crowds, San Juan Islanders as well as Victoria residents, attended each day. A Mr. Courteney acted as solicitor for friends of the Dwyers; Boyce, McKay, and Warbass attended; and the Hawaiian consul also was in court to protect the interests of the Hawaiians. All but Nuanna (whose size-seven boots matched the footprints found at the murder site) and his friend Charlie were released after initial investigations. The two were remanded for a week so that more evidence could be gathered.

During the week McKay was allowed unsupervised visits with Nuanna; what took place during the visits is not known, but when hearings resumed, McKay testified that Nuanna had in the jail yard confessed to complicity in the murders; he later signed a written statement. In an effort to shift some of the blame, Nuanna said he knew where the stolen watches were and led McKay and the assistant jailer to a spot near Charlie's shack on Kanaka Row along Humboldt Street, north and west of today's Empress Hotel, where the watches were recovered. McKay could personally identify Dwyer's large watch that he had seen many times in the past. At the final hearing Mr. Johnson prosecuted for the United States, Mr. Jackson "watched the case for the prisoner" ("Police Court," June 18, 1873), Courtney appeared again for the friends of the Dwyers, and Warbass was given a special invitation to sit on the bench.

The judge decided that there was not enough evidence against Charlie and ordered his release, much to the dismay of the Americans. Warbass testified at the hearing as San Juan County justice of the peace and submitted a warrant for Joe Nuanna's extradition to the United States. The warrant was approved and Nuanna was prepared for transfer to Port Townsend, on the Olympic Peninsula across the Strait of Juan de Fuca from San Juan Island, for trial in the Third District Court of Washington Territory. He was eventually transported on the Eliza Anderson, manacled at the ankle to one of the steamer's stanchions for security. The Daily Colonist reported that "he seemed as happy as though he were starting on a wedding tour, or was about to visit a circus, instead of upon the journey that ends in eternity" ("Joe," October 29, 1873).

The Trial and Hanging

Shortly after arriving in Port Townsend, Nuanna went on trial in a courtroom filled with San Juan Islanders who had known both the prisoner and the victims. The trial went on for three weeks. He seemed relaxed and carefree, apparently convinced he would not be found guilty. But among the witnesses was Minerva Hannah, who described how she lent Nuanna the shotgun and his strange behavior when he returned it. She was then asked about the pouch of shot that she had given Nuanna with the gun; she said that she had made the sack herself and went on to describe it in detail down to the fabric, construction, and stitchery. When Boyce produced the pouch he had been holding in evidence she identified it immediately, and Boyce explained where he had found it. It was, to the jury, the final piece of compelling evidence, and Nuanna was found guilty and sentenced to be hanged the following March.

Faced with the verdict, Nuanna confessed, although reportedly without remorse or regret, to the murders and additionally that he had murdered William Fuller the year before. Not only had he murdered him, but he had attended Fuller's funeral (standing, remembered an indignant Lila Hannah Firth, right beside her during the proceedings) wearing Fuller's shoes. Islanders were surprised at his confession, as the Hawaiians were such familiar neighbors in the small community that it had never occurred to anyone to suspect one of them of the crime. Nuanna had assumed from Fuller's lifestyle and appearance that he was wealthy, and he wanted retribution because Fuller had destroyed some quail traps that Nuanna had placed on his property and that were killing Fuller's chickens.

The motive for slaying the Dwyers was the money he thought would be in their house after Harry Dwyer sold his sloop (the sale took place at Kanaka Bay). He said he and Indian Charlie had it all planned; after killing Harry in his field, they would go to the house and Charlie would cover Selena, while Joe searched the house, but the plans went awry. Nuanna shot Selena but only wounded her, so he shot her again, but still hadn't killed her so he beat her head in with the gun stock, leaving the blood evidence. And the Dwyers were only the first of a number of islanders that Nuanna named as chosen for their next attacks -- all settlers perceived as well-to-do and likely to have money on their properties. One family was so unnerved at the close call that they soon packed up and moved off San Juan Island.

A scaffold was built for the hanging in Port Townsend at Point Hudson. Port Townsend residents, numerous Klallam Tribe members, and a large contingent of San Juan Islanders began to arrive by 9 a.m. for the 10 a.m. execution. Stephen Boyce, now San Juan County Sheriff following the county's formation the previous October, was in charge of the proceedings. Nuanna asked Boyce that his hands not be tied and that the hanging be quick; Boyce said he would do his best. Shortly before the appointed time, Boyce escorted Nuanna, seemingly at ease and in good humor (although he complained that the coffin he saw awaiting him hadn't been painted) to the gallows, accompanied also by the sheriff of Jefferson County (where the proceedings were taking place) and a clergyman. Nuanna stood talking to the priest for a few minutes and then mounted the scaffold where he addressed the spectators; he took off his cap and, reported the Daily Colonist, said, "'I am very sorry for what I have done; all hands, goodbye,' and waved his cap to the crowd" ("Joe," March 7, 1874).

The noose was put around his neck, and at 10:05 a.m. he dropped through the scaffold. But instead of swiftly breaking his neck, the rope slipped up beneath his chin, and he began to slowly and painfully strangle. No one had thought to test the new rope that was being used, and it was too stiff and Nuanna of too slight a build, to have the rope instantly stretch to its full length and tighten properly. Spectators watched in horror as Nuanna thrashed and fought for minutes, but no one knew quite what to do. Eventually Boyce swung himself down, added his weight to the rope, and tried to push the noose lower with his boots. It was an agonizing 20 minutes before the attending doctor pronounced Nuanna dead. Boyce was devastated and vowed never again to be a part of or spectator to a hanging. Town saloons were soon packed with those who had witnessed the dreadful scene and were deeply shaken; Port Townsend was never the site of another hanging. And Joe Nuanna's short life had come to a dramatic and horrific end.