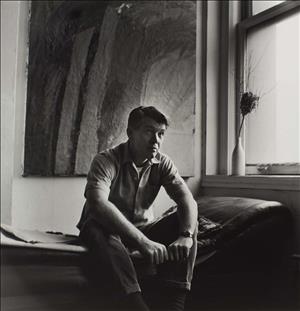

The painter William Ivey began his art career at a young age, with art instruction at the Cornish School in Seattle. Ivey's interest in pursuing art as a profession was interrupted by World War II. After the war, he was able to complete his studies in California, focusing on study under several artists noted for their work in the Abstract Expressionist style. Following his return to the Pacific Northwest, Ivey developed his own style of color composition in his paintings, which gained recognition over time with the Northwest School of artists and audiences. Noted as a somewhat reclusive artist, Ivey achieved a large body of artwork in more than four decades of painting.

Pacific Northwest Roots, Northwest School Artists

William C. Ivey was born in Seattle on September 30, 1919, the fourth generation in a family of early immigrants to Seattle. Ivey's parents died when he was young, leaving him and his younger sister to be raised by their maternal grandfather and an aunt. Ivey grew up in the city's Capitol Hill neighborhood, not far from the Seattle Art Museum's original location in Volunteer Park. Ivey recalled visiting the museum after it opened in 1933, and he found inspiration in art. He graduated from Broadway High School and next attended the University of Washington, where he briefly enrolled in law school in 1937. He later recalled that this was a career choice affected by the fact that "my family were lawyers" -- it was not something he pursued, and he noticed "that I had been drawing and painting all this while" (Hackett interview).

Ivey's passion for the arts and drawing led him to enroll at the Cornish School, where he took drawing classes. Part of Ivey's attraction to the school was that local artists and musicians had previously taught there, including Mark Tobey (1890-1976), Morris Graves (1910-2001), and John Cage (1912-1992), all associated with the emerging art movement known as the Northwest School. In 1941, the U.S. entry into World War II put a hold on further art-school studies, as Ivey was drafted into the U.S. Army as a paratrooper. He served in the Aleutians, Africa, and Italy, sustained an abdominal wound during combat in 1944, and was discharged shortly thereafter.

Art Studies in California

Following the war, Ivey resumed his study of art in California on the G.I. Bill, the choice made more for its scene than for the reputation of the California School of Fine Arts (later San Francisco Art Institute), where he enrolled to study painting. Ivey has described his wartime experiences as something that only other veterans of the conflict could understand fully. Following the war's end, he had little tolerance for those he considered shallow or playing games. This intolerance led him to become physically confrontational at times and may have contributed to his lifelong aversion to the public with respect to his artwork.

In an interview with art historian Barbara Johns, Ivey described how his postwar attitude toward people impacted the relationships he had with art instructors and students alike during his time in California:

"I was pretty hostile. And I was not going to get involved in arguments with people. And if I didn't like something, I'd hit 'em. ... You see, the age difference wasn't that great, and here all of us had come back from the war; most of us had been in combat. And we had been through things he couldn't even imagine. We felt superior in most ways to the faculty" (Johns interview).

Ivey's art instruction at the California School of Fine Arts lasted from 1946 to 1948 and included studies under painters Mark Rothko (1903-1970) and David Park (1911-1960), and "one very elementary class" with Clyfford Still (1904-1980) (Swenson interview). Ivey was also influenced early on by Clayton Sumner Price (1874-1950), a painter who was working in an Abstract Expressionist style in Oregon. Student artists with whom Ivey formed associations while at CSFA included Frank Lobdell (1921-2013), John Hultberg (1922-2005), and Richard Diebenkorn (1922-1993). From these early encounters, Ivey credited Rothko with convincing him to work in a larger scale with canvases six feet and larger, while Price's artwork conveyed "a kind of spirit that I felt" (Johns interview). From Price, he adopted a painting process called "scumbled" that applied paint to surfaces in a layering effect for colors.

In his three years at the fine art school, Ivey developed an approach to his own painting that drew from the use of color by other artists who practiced in the Abstract Expressionist style, yet with compositions that relied on an absence of defined forms or applied labels. The creative process was a personal one for Ivey:

"Well, that's what I meant by what to paint, what is it you're trying to get down? I'm not talking about a realist or an abstractionist, or am I this or that. But 'What is my form?' ... As an individual. To express that which I have to express, whatever that may mean. That's what I'm getting at. So the idea was that you thought out through the tradition, through your own experience, that which you painted, and that became your form, became your painting" (Johns interview).

Ivey's outlook on painting even applied to details such as artwork titles, which he regarded as irrelevant and therefore, not necessary (most of his paintings were untitled). Often the size of the painting was the result of smaller paintings turning into studies for larger works, where the artist would continue to develop the idea onto a larger canvas.

As his command of painting technique matured, Ivey began to display his art in public. Around 1947, he exhibited work with gallery owner Betty Parsons, but the art scene had become too crowded for the artist. Ivey wanted a change of pace from the bustling art center of San Francisco, and so decided to return home to Seattle.

Return to Seattle

While the need for isolation to focus on his painting prompted Ivey's return to Seattle as a familiar place to undertake his work, he also used his return to familiarize himself with the work of other Northwest artists. The relocation allowed him to connect with artists he had known only by reputation, from his days at Cornish:

"[I]t got to the point where I really wanted to see other people's work, and discuss ideas, more than I could do as an occasional trip [to Seattle]. Then I met Mark Tobey, I met Richard Gilkey [1925-1997] -- a whole bunch of people at the time. We all had very different aesthetics, but there were so damn few of us, we had to get along. ... I'd see a painting someplace, at the [Northwest] Annual or at a little show, and if I liked it I'd try to get in touch with the artist. Rothko suggested I look up Mark Tobey. I finally did. Also Morris Graves. Callahan. All those people were important to me in one way or another" (Hackett interview).

Ivey had married Helen Taylor (1922-2004), and the return to Seattle coincided with the birth of their daughter Kathleen. Meanwhile, Ivey's painting had evolved from earlier attempts that he described as belonging to the "Ash-Can School" and were made in the vein of Abstract Expressionist but also represented his own personalized style.

Ivey was able to supplement his income as a social worker for the City of Seattle, working during the day and spending up to eight hours each night painting in his studio. He recalled how artists in Seattle at this time had a difficult if not impossible time making a living at art. At the Western Washington Fair in Puyallup in 1950, Ivey exhibited an untitled oil painting as entry No. 38 out of more than 100 artists. In the early 1950s he sold his first painting to Zoe Dusanne (1884-1972) for her pioneering modern-art gallery and exhibited other colorful abstract-composition paintings in group shows such as the 1952 Northwest Annual at Seattle Art Museum. In December 1953 he was included in a four-artist show at Seattle Art Museum organized by Dr. Richard Fuller (1897-1976), with three other Northwest avant-garde painters, Jack Stangle (1927-1980), Ward Corley (1920-1962), and Richard Gilkey.

As his personal relationships with many local artists grew, Ivey helped initiate the short-lived Artists Gallery in 1958 with fellow artists James FitzGerald (1910-1973), Margaret Tomkins (1916-2002), Louis Bruce, and Alden Mason (1919-2013). He also found new opportunities for group exhibitions with the Henry Art Gallery's Northwest Invitational on the campus of the University of Washington and brief representation by the Hall-Coleman Gallery in 1959.

Beginning in 1958, he taught private lessons in painting in Seattle until 1965, as well as two summers as a visiting instructor at the San Francisco Art Institute in 1963 and 1964. Ivey's views on teaching were self-critical where the practice of art was at stake: "I think if you worked for a few years, supported yourself as best you can and kept painting regularly, then maybe a university is fine, because you've established yourself as a painter, in some way" (Swenson interview). Ivey continued to teach painting later in his career, as a visiting artist in residence at Reed College in 1967, at Highline Community College in Seattle, and for small groups at a studio shared with the painter Frank Okada (1931-2000) in downtown Seattle.

A strong work ethic was central to Ivey's philosophy as a successful artist. His outlook was one that called for a dedication to painting that went beyond it as a profession, where personality, morality, and personal choice all weighed into the creative process:

"I've seen people who were pretty gifted who quit after a while because they simply couldn't keep caring that much. That's the difference -- if you just care so goddamn much that you can't stop painting, you've got to do it. There's no heroism in it. This is just the way you are. You've got that disease, and so it's really not an issue. Even the discipline is easy, if you really want it badly enough" (Hackett interview).

In 1960, Ivey found renewed interest in his artwork on the commercial front in Seattle. He began being represented by the Gordon Woodside Gallery (later Woodside/Braseth Gallery), where he would remain for the rest of his career, with regular shows of his paintings and other artwork. Also in 1960, Ivey received major financial support for his work through the Ford Foundation, which allowed him to paint fulltime. The two decades that followed would bring additional recognition on the local arts scene.

Expanded Range of Exhibitions

In his introduction to a retrospective exhibition of Ivey's paintings at the Henry Art Gallery in 1989, senior curator Chris Bruce related the reaction of Robert Sarkis, a longtime art collector in Seattle and one of the exhibition's organizers, when he first saw Ivey's work in a solo exhibition in 1966:

"[Sarkis had] the realization that here was an artist whose paintings had a special kind of energy. These were rich, layered paintings, with organic presences, with scumbled surfaces and tonal colors, with traces of life and the outdoors. They have unmistakable personalities. These paintings had the madness that good art should have" (Bruce, 2).

The 1960s saw Ivey's use of color sway away from his earlier paintings done in a more Rothkoesque style to compositions where all forms were dissolved, with a notable preference for more cool colors such as blue and gray, which predominated throughout. His views on color were inexorably linked to his painting style:

"[T]o some extent my attitude toward color is conceptual, just as my attitude toward painting is somewhat conceptual. I use stuff around me, but it always goes through a change to conform to conceptions of what painting is" (Hackett interview).

The results of Ivey's labors continued to gain attention through the 1960s. In 1963 he contributed artwork to a group exhibition shown at the Center Art Pavilion at the Seattle Center and at the Whitney Annual in New York. The Seattle Art Museum featured Ivey as a solo artist in exhibitions held in 1964 and 1975, the latter curated by arts patron Virginia Wright (b. 1929) for the museum as a traveling exhibit of 32 artworks that later went on view at the Portland Art Museum. Wright was direct in her critique of the 1975 selection of works assembled from institutions and other collectors of Ivey's work: "His recent work has more authority and a stronger impact but there is still that hard-won quality of a thing slowly and thoughtfully evolved that marks all of his work and makes it so appealing" (Wright, 11).

In 1966, Ivey was featured in the international art scene (a rarity during his career) through a one-artist exhibition organized by the painter John Franklin Koenig (1924-2008) for the Galerie Arnaud in Paris. In November that same year, he was a visiting artist at Stanford University. Ivey was awarded a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts in 1967.

As his reputation grew, Ivey remained steadfast in his dislike of public attention. In particular, he preferred not to attend his own gallery openings and exhibitions. In a 1974 interview with Sally Swenson, Ivey offered some strongly worded insights into this lifelong practice as a working artist:

"I just find them extremely painful to go to. ... I just hate the kind of superficiality of the conversation, that's all. I'm not afraid of people -- I can go do it. I don't do it, simply because I get so goddamn tired of somebody coming up to me -- some perfectly decent person, who normally does not talk this way -- and saying 'Oh, Mr. Ivey! It's so beautiful!' Well, shit, you know -- I really don't enjoy that ... and then I have to respond in kind. ... I suppose everybody knows I don't go to my openings -- most people seem to know it. And they probably think it is shyness ... and that isn't the case at all -- it's just plain distaste, and I don't have to" (Swenson interview).

Regardless of his outlook on public art openings, Ivey continued to exhibit his work through the Woodside/Braseth Gallery. In 1982 he secured a public commission for the largest painting he had ever done, for the King County District Court in Issaquah (Ivey generally avoided applying for public art commissions). The following year, the King County Arts Commission named Ivey as its Artist of the Year for 1983 and awarded him a grant of $25,000. The painter used the funds to construct a new studio behind his home in the Queen Anne neighborhood of Seattle.

At the pinnacle of his career, a retrospective of Ivey's paintings was exhibited at the Henry Art Gallery in 1989. The exhibit received wide acclaim in national arts publications such as Art in America and ARTnews; and the senior curator for the Henry observed that these "great paintings signify a life force held by the artist for our contemplation and examination" (Bruce, 2).

In 1990, Ivey was diagnosed with skin cancer on his stomach. Following a lengthy battle with the disease, he died on May 17, 1992, at the age of 72. His paintings and other artworks are now found in more than 300 collections, including the Seattle Art Museum, the Henry Art Gallery, and the Tacoma Art Museum.