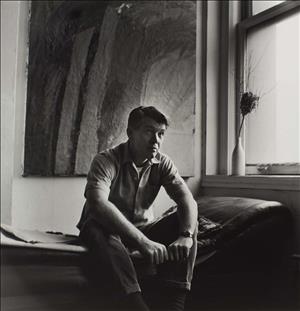

On April 8, 1964, William Ivey (1919-1992) marks his debut as a painter working in the Abstract Expressionist style at his first one-man show at the Seattle Art Museum (SAM). The exhibition features 32 assorted paintings and drawings by Ivey and reflects a period of key activity and recognition achieved by the artist in the 1960s. The solo show, at a time that public recognition of his art is becoming a reality in the Pacific Northwest, is important as a milestone in the artist's career.

Early Group Show at SAM and Painting Philosophy

The solo exhibition in 1964 was not the first time Ivey exhibited work at the Seattle Art Museum, then located in Seattle's Volunteer Park. He was part of a four-artist group show at the museum in 1953, along with Northwest School painters Ward Corley (1920-1962), Richard Gilkey (1925-1997), and Jack Stangle (1927-1980). The inclusion of eight paintings by Ivey in the group show was all the more remarkable in that it afforded him early recognition of his work, just five years after he completed painting studies at the California School of Fine Arts (later San Francisco Art Institute) and returned to Seattle in 1948.

An art review of the 1953 group exhibition by fellow artist Kenneth Callahan (1905-1986) that appeared in The Seattle Times remarked that out of the four artists, Ivey's "purely nonobjective approach" to his work was "the hardest to take for the average layman," given his abstract style and use of color to create compositions that had no recognizable content (Callahan). For his part, Ivey thought little of art critics as reviewers, including Callahan, whom he considered more of a spokesman for the Seattle Art Museum than an objective reviewer. He even confronted the fellow artist by letter after one particularly negative review:

"[H]e was terrible. He worked at the Seattle Art Museum, and I've never been sure that Ken wrote those things, but I remember once we had a confrontation by letter ... he said he wasn't a reviewer or a critic -- he was a publicist for the Seattle Art Museum, that was the way he put it, which is really the only place in town, really, he reviewed" (Swenson interview).

Undaunted by public perception of his work, Ivey's painting style was influenced by the abstract color compositions of artists such as Clayton Sumner Price (1874-1950), Clyfford Still (1904-1980), and Mark Rothko (1903-1970); the latter two artists he studied under in California. Instead of focusing on landscapes or natural forms, Ivey painted free-formed artworks that eschewed distinct forms in favor of using colors to capture forms perceived as emerging or dissolving together. Both the terms "Abstract Expressionist" and "Abstract Impressionist" have been applied to Ivey's artworks over time.

Ivey reflected on how his approach to his work was focused on how he saw color as part of the creative process: "[T]o some extent my attitude toward color is conceptual, just as my attitude toward painting is somewhat conceptual. I use stuff around me, but it always goes through a change to conform to conceptions of what painting is" (Hackett interview). As another indication of his preference for process over defined elements, the catalogue raisonné of Ivey's art consists for the most part of untitled artworks, with few exceptions.

Over the next decade, Ivey continued to exhibit his paintings in the Pacific Northwest, first from 1950 to 1957 in group exhibitions at the Zoe Dusanne Gallery on Lakeview Place in Seattle, where he made his first commercial sale, then at the short-lived Artists Gallery co-operative (which he founded along with Margaret Tomkins and James FitzGerald) in 1958 and the Hall-Coleman Gallery in 1959. His work was also included in the Henry Invitational at the Henry Art Gallery on the University of Washington campus and the Northwest Annual at SAM. Ivey found long-term commercial representation as an artist with the Gordon Woodside (later Woodside/Braseth) Gallery in Seattle starting in 1960. The Woodside offered Ivey several solo exhibitions in the following years -- five shows between 1962 and 1973 -- which were popular events with art patrons even though the artist was rarely known to attend his own gallery openings.

Expanded Recognition of Ivey and His Work

The 1960s saw some duality in public recognition of Ivey as a painter and his reputation as an artist: While he was becoming well-known in Northwest art circles for his painting style, he continued to struggle with recognition by the art world at large. This may have been partly due to Ivey's views on self-promotion (he avoided the limelight) and preference for privacy over notoriety as an artist. On at least one occasion involving a group exhibition at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C., Ivey was vocal about his opposition to being included without being consulted first.

Ivey's slow recognition as an artist may also be attributed to how he defined his painting style, without overt distinction as to the compositions and use of colors. In the introduction to a catalogue for Ivey's second solo show at SAM in 1975, the avant-garde art patron Virginia Wright (b. 1929) noted how Ivey's reputation was inexorably tied to his painting style:

"He [Ivey] did not invent a single personal format that was 'readily identifiable' in the way that Newman, Rothko and Pollock did. The superficial student of Ivey's work is disturbed by unsettling shifts in his manner. It is hard to reconcile the somber compositions, Still-like in their darkness but without Still's ferocity, with the vernal, light-filled canvases and again, with others full of strong color that, in mood, lie somewhere in between. It is hard to reconcile these stylistic differences because they follow no chronological pattern" (Wright, 8-9).

For his part, Ivey was a committed painter, having once remarked that painting is something that must be constantly done all the time in order to be a successful artist. His work was his own; and while he acknowledged influences like Still, Rothko, and others who were concurrently practicing in the Abstract Expressionist style and movement, Ivey viewed his work as one of a personal nature that embodied both his attitude toward art as a way of being and his own subconscious nature:

"I suppose, in any painting, my primary interest is in those qualities which make up the painting for me. I'm not conscious of the relationship all the time I'm painting, but the qualities of hard and soft, fast and slow, thin and thick -- all of those things are for me metaphors for qualities I see in art. I think of a painting as creating a form to which I can truly respond. I use stuff around me because it's an organizing principle. I try to deal with those qualities which seem to me to stand for a living process. A sense of that process has to be in the work" (Hackett interview).

A steady succession of exhibitions and more than a few accolades paved the way for Ivey's ascendance as a painter beginning in 1960. In that year, he was awarded a Ford Foundation grant, which allowed him to paint full time (he had been working since 1948 as a social worker in Seattle to support his art). The year closed out with Ivey showing small-scale paintings at a group show held at the Smith Tower Gallery, along with other regional artists such as Walter Isaacs, Margaret Tomkins, Frank Dobbins, James FitzGerald, and Wendell Brazeau.

Reviewing another group show held in 1963 at the Center Art Pavilion of the new Seattle Center, art critic and future novelist Tom Robbins (1932-2025) remarked how the artist's single work in the show, an oil-on-canvas painting titled Landscape, served to "elevate William Ivey to the alpine position in the hierarchy of Northwest painters that he so deserves" (Robbins). That same year, Ivey taught painting during the summer session at the San Francisco Art Institute.

First Solo Show at SAM

After four years of steady representation by the Gordon Woodside Gallery, with both solo and group showings of his paintings, Ivey was ready for his own solo exhibition at the Seattle Art Museum. Wright has characterized the timing for this public display of his work as "wrong" for Ivey, in that "Seattle museum goers, preoccupied with the new styles and artists of the sixties, seem not to have paid much attention" (Wright, 9).

Regardless, the opening held on April 8, 1964, saw a selection of 32 assorted two-dimensional artworks by Ivey, most of them oil-on-canvas paintings that were untitled and averaged six feet in size, with a few tempera drawings also included. A second artist, Joseph Petta Jr. (1936-1998), was featured in a separate gallery on the same opening night. The event, which ran from from 8 to 10 p.m., was well-attended and included patrons such as Millard B. Rogers, Dwight E. Robinson, Stephen W. Williard, A. Michael Murray Jr., Elwell C. Case, Stewart Ballinger, and Paul Roland Smith. The exhibition remained on view until May 3, after which Ivey returned to the San Francisco Art Institute for another summer of teaching.

Ivey finished out the 1960s with an additional one-man exhibit at the Galerie Arnaud in Paris in 1966 and as a visiting artist at Stanford University in California that same year. In 1967, he was invited to be artist-in-residence at Reed College in Portland, Oregon. Collectively, these opportunities helped to support Ivey as he continued his studio work as a painter, while expanding his visibility on both the Northwest regional and the national level.

The Seattle Art Museum followed up with second solo exhibition for Ivey in 1975, which included a color catalogue of 27 paintings done between 1953 and 1973 and curated by Wright for the museum. This exhibition was on view at SAM from January 24 to March 9 and then traveled to the Portland Art Museum, where it was shown from March 27 to April 20, 1975.

As of 2020, the Seattle Art Museum permanent collection included nine paintings by William Ivey, ranging chronologically from his Landscape (oil on canvas, 1961) to Untitled (oil on canvas, 1977), and his work continued to be represented by the Woodside/Braseth Gallery in Seattle.