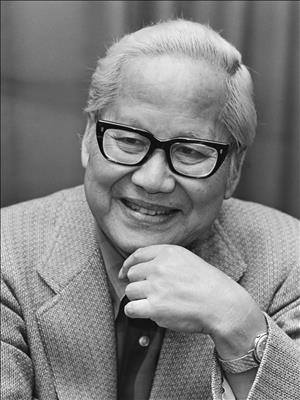

Growing up in Seattle, Chinese-born Keye Luke knew that he wanted to be an artist, and he did just that. To his surprise, he also became a movie, television, and stage star. In the 1930s, he played teenager Lee Chan, Honolulu police detective Charlie Chan's "number one son," in a series of popular movies. In the 1970s, he became just as famous as Master Po, a blind sage in Kung Fu, a hit television series. In a screen, stage and television career that lasted more than half a century, Luke racked up more than 150 credits as a movie, television, and voice actor. A founding member of the Screen Actors Guild, he was honored in 1991 with a star on Hollywood Boulevard's Walk of Fame.

Artistic Leanings From an Early Age

Although his family had already lived in California for two generations, Luke was born in 1904 when the family was visiting Guangzhou, China, then known as Canton. They moved to Seattle when Luke was 3. Another branch of the family included a cousin, Wing Luke, after whom a Seattle museum and school are named.

Keye Luke's father, Lee Luke, had been an art dealer in San Francisco before coming to Seattle. Lee Luke & Co., described as "Importers of High Grade Chinese and Japanese Art Curios," opened in 1910 in downtown Seattle on 3rd Avenue between Marion and Madison streets. The shop sold high-end imports, including teak, rattan, and ebony furniture; ivory, brass, bronze, and fine porcelain objects; and silk kimonos, "mandarin coats," opera coats, and dressing gowns.

As a child, Keye Luke went to a Seattle Chinese academy as well as the public Pacific Grammar School. In 1917, some months after the United States entered World War I, young Luke was one the school's three finalists in a Seattle Daily Times composition contest on the theme "Why Buy a War Bond?" But his real interest was art. He was inspired in large part by a kindly Seattle librarian who helped him select art books. She also broke the rules and let him take reference books home overnight. In 1919, by then at Franklin High School, he joined a Times youth organization called Junior Citizen ("Our motto -- Love, Loyalty and Service"). Its members provided poems, stories, and art for the paper's youth page for prizes and cash.

Years later he remembered earning $5 from Junior Citizen. A frequent contributor, his 1921 pen and ink drawing called "A Junior Santa" showed a teenager delivering Christmas toys through the snow to sad-looking needy children. The paper praised his "exceptionally fine drawing" of Santa Claus on a rooftop and posted it in its offices as well as running it in the paper on Christmas Day. He also submitted cartoons, including one discouraging plagiarism among other junior citizens.

By the following spring, however, the Times kid's page announced that "Keye Luke was too busy with Franklin annual work to send anything in." He was the art director of the Class of 1922 yearbook, lavishly illustrated with his pen and ink drawings. The yearbook wrote of him: "Could that boy throw ink!" and in a senior prophecy cast him as a world famous artist. Luke also played baseball on a field at 12th and Yesler. He had no interest in acting, and said that he was such an introvert he skipped English class when he was scheduled to give a talk in front of the classroom as part of the school's "oral interpretation" curriculum.

Into the Art World, Off to Hollywood

After graduation, he was soon part of the town's adult art scene. The Seattle Art Club's 1922 Halloween party featured trendy young artists showing off their avant-garde costumes on the dimly lit dance floor, surrounded by décor featuring cubist cats and bats. Entertainment included Cornish School dancers and a "chalk talk" with Keye Luke. His illustrations also appeared in Town Crier, the official publication of the Seattle Fine Arts Society.

Another art-minded Seattleite was his friend Richard Fuller, a few years older than Luke, and later a founder of the Seattle Art Museum. In a 1973 interview Luke recalled Fuller showing him his jade snuffbox collection, adding, "Both he and I were championing Mark Tobey in those days -- when a great deal of art in the Northwest had to do with painting Douglas firs." (Voorhees).

As a young man, Luke dreamed of art school -- but his parents told him it would be more practical to become an architect. He duly enrolled at the University of Washington as an architecture major, but his father's sudden death meant he had to leave college and go to work, presumably to help support his widowed mother, two brothers, and two sisters. He began making a living as a commercial artist, and working for an advertising agency. One of his clients was the Fifth Avenue Theatre, then a movie palace. Besides newspaper layouts and lobby cards, he came up with a slogan for the theatre: "an acre of seats in a palace of splendor." In 1926 and 1927, he took on a big project -- a Chinese-themed mural for the tearoom of the art deco Bon Marché department store.

His local movie promotion work led to similar assignments in Hollywood, and in 1927, he moved to Los Angeles, where he began a successful career working for the Fox (later Twentieth Century Fox) publicity department. His elegant rendering of a giant ape graced lobby cards and other promotional materials for the movie King Kong. He was hired as muralist, painting the fairy tale gardens and a huge ceiling mural inside Grauman's Chinese Theatre, and he served as a technical adviser to art directors on Asian-themed movies. Alongside his commercial career, Luke took classes at the Chouinard Institute, a leading art school that later became part of what is now Cal/Arts. In the 1920s and 1930s, his work was exhibited in Seattle, Santa Barbara, and Los Angeles, as well as in Paris and Vienna, and he illustrated a book about Marco Polo. In 1938, The Los Angeles Times said his work "formed a bridge between Asian and Western art" (Keye Luke: Beyond ..."). His style was often compared to that of English illustrator Aubrey Beardsley.

In 1934, the 27-year old Luke was offered a lead role in Ho for Shanghai, a film meant to be a sequel to the Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers musical Flying Down to Rio. The studio wanted a leading man for famous Chinese-American movie star Anna May Wong. By the ironclad rules of the day, any love interest for her had to be Asian. The studio had to look no farther than the publicity department where Luke, a suave, good looking young man with an amiable personality, a great speaking voice, and a reputation as one of Hollywood's best dressers, was already working. The project fell through, but not before getting Luke some publicity about his casting, provided by his friends Louella Parsons and Hedda Hopper. The women were syndicated Hollywood columnists for whom he supplied line drawings and caricatures of movie stars.

'The Nice Chinese Guy Down the Block'

Later that year, when the head of advertising at Metro Goldwyn Mayer, who was also Luke's former boss at Grauman's Chinese Theatre, asked him to come over to the studio for a meeting, he brought his art portfolio. He was surprised to learn the studio wanted to audition him for a speaking part as a young doctor in a Greta Garbo picture, The Painted Veil. He later said he was often cast as doctors, lawyers, business executives, and other professionals, what he called "good Boy Scout roles ... the nice Chinese guy down the block" (IMDb).

He got the part, and he and Garbo exchanged dialog on a moving treadmill in front of a process shot of a Chinese village. When she tripped, he grabbed her and saved her from a three-foot drop to the studio floor. Years later, he said, "I will never forget her looking up at me with those sea-green eyes," adding that he told himself, "you are holding screen immortality in your arms, my boy" (Skreen). Luke described her as "exquisite in close ups ... the camera was her best friend," adding an observation from an artist's eye: "She was a true beauty from the neck up, but her body was stocky, her feet long" (Bawden).

Also in the cast, playing a Chinese general, was Warner Oland. The Swedish-born actor specialized in playing Asian characters. He (and his whole family, according to Luke) had epicanthal eye folds common among some Scandinavians --including the indigenous Sami population. This allowed Oland to play Asian roles without the tape used on Caucasian actors playing Asians. A host of twentieth century stars including Marlon Brando, Mary Pickford, Katharine Hepburn, Alec Guinness, and Mickey Rooney all played such roles which came to be called yellowface.

Oland also starred in the Charlie Chan detective series. The highly popular films, based on a series of novels, were old-fashioned puzzle mysteries, laying out all the clues for the audience. Chan was a famous Honolulu police detective, often consulted on mainland or international cases. A year after Painted Veil, with a handful of other credits now under his belt, Luke auditioned with Oland to play detective Charlie Chan's oldest son, Lee, in Charlie Chan in Paris.

After the screen test, Oland said, "Hire the kid" (Bawden). Luke had already produced some artwork for the series -- a drawing of Oland for newspapers and some Chinese characters for publicity materials. He had also worked amicably with the screenplay writer on a previous picture. When the writer heard Luke had been cast, he promised the young actor that he'd fatten up his part, and Luke said he came through.

While Oland's casting seems unconvincing to modern audiences, his Charlie Chan movies were popular in China where films featuring arch villain Fu Manchu had been banned as degrading and racist. Oland was mobbed by local fans on a 1936 trip to Shanghai and thoroughly enjoyed himself, staying in character as Charlie Chan throughout the visit, a habit the eccentric actor also developed on the Charlie Chan sets.

Charlie Chan was portrayed stereotypically but always as someone who was highly respected, both professionally and personally, especially by upper-class characters. When white characters made racist remarks about him, other white characters would upbraid them. Oland's Charlie Chan had a genial but dignified manner and wore white tropical suits. He smiled a lot and spouted what sounded like fortune cookie philosophy in a Chinese accent with a Swedish lilt.

Charlie Chan's energetic, optimistic, goofy son Lee, however, was thoroughly Americanized. At a machine-gun pace, Luke delivered lines such as, "Gee pop, What are you always stopping me for? Why don't you give me a chance to clean this case up for you?" and "Aw gee, Pop, when are we gonna arrest somebody?" Luke went on to make eight Charlie Chan films with Oland, playing a teenager until he was past 30. Luke and Oland became fast friends, and Luke called the portly actor "Pop" both on film and in real life.

The Seattle Daily Times, writing about its hometown boy, said Luke symbolized "the modern young Chinese." ("Key Luke Stars ..."). Lee Chan's all-American boy persona was emphasized in Charlie Chan at the Olympics, in which he goes to Berlin and wins a gold medal in swimming for the U.S.A. Luke said the Chan films did a lot of promotional events for the series, and he enjoyed greeting fans. "Parents invariably came to push a baby at me, saying 'Here's OUR number one son'" (Skreen).

Racism, Subtle and Otherwise

But despite his cheerful public demeanor, Luke later said that Los Angeles in the 1930s was informally but definitely segregated. He avoided all-white areas such as Beverly Hills and didn't go into downtown department stores. Caucasian actors he'd worked with would ignore him if they met on the street. "Asians were invisible ... we knew our place. One step back." He said the Chan films were important because "they deflated a lot of the current myths" (Bawden).

In 1937 the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences published its first Players Directory, a casting aid with headshots of actors in categories such as "leading man," "comic," or "character." Luke was in the "Oriental" section, right next to the category called "Colored." Roles for Asians were limited to supporting players, with white actors playing Asian lead roles. That year, Luke appeared as another elder son in the prestigious blockbuster The Good Earth, based on the Pearl S. Buck novel about Chinese peasants fighting off famine and locusts. The yellowface casting of Paul Muni and Luise Rainier as his parents, Wang and Olan, was made even more implausible by Muni's New York accent and Viennese Rainier's clearly German one.

In 1938, Oland died on a trip home to Sweden at 58. The actor, who had been known to drink his lunch of martinis from a thermos on the set, and once had to be propped up by extras in a crowd scene while falling-down drunk, had been in ill health. Luke told the press that his grief was "that of a son who had lost a father" (Hays).

Over the years, Luke loyally defended Oland's cross-racial casting, saying Oland gave "a faithful portrait of a Mandarin scholar" (Folkart), and noted that Oland made a point of studying Chinese culture and reading books of Chinese philosophy, some provided by Luke. He also gave Oland's casting a pass by saying there really wasn't a Chinese actor working in Hollywood who had the tubby silhouette of the detective as described in the series of novels on which the films were based. He summed it up by saying, "A Chinese role should be played by a Chinese actor if he can play it. But if an actor can you make you feel the reality, that person should get the part" (Flint).

Casting aside, Luke was also a lifelong defender of the Chan character itself which, as the years went by, was criticized as a demeaning stereotype. Luke said, "They think it demeans the race ... Demeans! My God, you've got a Chinese hero!" (Huang). Luke did criticize other Asian-themed movies that he found offensive such as the 1985 Michael Cimino film Year of the Dragon.

After Oland's death, and after unsuccessfully asking for more money, Luke quit playing Lee Chan. In the next picture in the series, with Oland's replacement, Sidney Toler, it was explained that number one son had gone away to college and number two son would take over as Charlie Chan's assistant.

Luke reprised the role twice more in two Chan films, The Feathered Serpent (1948) and The Sky Dragon (1949). At the age of 44, he was five months older than Roland Winter, who played his father. Later, as a voice actor in the 1970s, Luke played Charlie Chan himself in the animated series The Amazing Chan and the Chan Clan. One of the detective's numerous children was voiced by a young Jodie Foster.

The Original Kato

After the Warner Oland series, Luke went on to practically corner the market in Chinese or Japanese roles in Hollywood. No job was too small, and often his work was uncredited, but there were some bigger roles as well. He played Dr. Lee Wong How, an ambitious young intern from Brooklyn, in five pictures in the Dr. Kildare series set in a New York hospital and starring Lionel Barrymore as his boss, Dr. Gillespie.

In 1940 he had a starring role as San Francisco detective Jimmy Wong in Phantom of Chinatown. The role was a spinoff from a series about an older Chinese detective named James Wong. He had been played by an actor who was the son of an English father and South Asian mother from India, and who used a Russian stage name – Boris Karloff.

In 1940, Luke donned a chauffeur's uniform and a mask to play Kato, the wheelman and sidekick to the undercover crime fighting hero Green Hornet. Kato also slipped into a lab coat while inventing cutting-edge crime fighting technology. Luke said that as Kato he was the first actor in Hollywood to use karate chops. This proved difficult with taller villains, as Luke was 5-feet-6. The fights were staged on staircases, or Kato would chase the bad guys across uneven ground and jump onto a conveniently placed apple box to deliver the final blow. Kato was played a generation later by another actor from Seattle, Bruce Lee.

Originally, Luke was asked to use a Filipino accent as Kato, but on screen the character declared himself to be Korean. By 1940, the Japanese background of the character had become problematic due to global politics. During World War II, Luke was usually cast as the good guy Chinese ally, not the Japanese enemy, in large part because of his amiable Number One Son image. He also had a featured role as a Filipino boxer in Salute to the Marines. But in Across the Pacific he played a Japanese spy in a fedora, snooping around Humphrey Bogart's hotel room with a flashlight.

Marriage and Family

The 1940 census indicates that Keye Luke lived at 842 North Gardner Street, in a one-story, two bedroom Spanish style North Hollywood bungalow. The head of household was listed as 50-year-old Ethel Davis Blaney. Her two children, son John, 20 and namesake daughter Ethel, a college student at 19, also lived there. Keye Luke, 35, was described as a lodger.

Two years later, in May of 1942, Luke's old pal, Hearst Hollywood columnist Louella Parsons, wrote in her nationally syndicated column that Ethel Davis Blaney, whom Parsons characterized as "a non-professional" and Keye Luke had been married in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Mrs. Blaney's attendant at the ceremony was her daughter. Luke was reported to be dedicating a new series of drawings, to be published soon, to his new bride. Parsons called Keye Luke, "one of the best Chinese actors anywhere," and "a very fine artist."

The venue for the white bride and Asian groom was no doubt chosen because such interracial marriages were not against the law in New Mexico as they were in California. The marriage would last until his wife's death in 1979. Keye Luke legally adopted his wife's daughter, who used the name Luke until her own marriage.

In the 1950s, with the arrival of television, Luke kept adding to his credits, appearing in series such as Gunsmoke, December Bride and My Little Margie. He also appeared uncredited in big movies such as Love is a Many-Splendored Thing and Around the World in Eighty Days.

In 1958 Luke made his stage debut on Broadway. He took voice lessons to prepare for the role of Master Wang in the Rodgers and Hammerstein hit musical Flower Drum Song. He later said the cast knew it had a hit in Boston during out-of-town tryouts when petite vocal dynamo Pat Suzuki belted out "I Enjoy Being a Girl" and brought down the house. (Suzuki had been discovered in Seattle by Bing Crosby at Seattle's Colony supper club on Virginia Street in the mid-fifties.)

In his teens, Luke's parents had squelched his plans to go to art school. In his twenties, he'd viewed his move to Los Angeles as a stop on his way to either the Chicago Art Institute or the Art Students League, or maybe Paris. Now, in his fifties, Luke found himself in New York with Flower Drum Song. He immediately enrolled at the Arts Student League to study painting, telling an interviewer years later, "It was like a dream come true!" (Voorhees). He ran into Greta Garbo walking down a Manhattan street. The actress with whom he'd played his very first movie scene was now famed for wanting to be left alone, and he didn't invade her privacy. After the two-year Broadway run, Luke toured with Flower Drum Song for two more years.

In 1960, his cousin Wing Luke, then a Washington State assistant attorney general, came to Los Angeles to attend the Democratic National Convention where John F. Kennedy was nominated for president. Both Lukes attended Washington State caucus meetings. Wing Luke is also said to have visited cousin Keye backstage on a trip to New York during the run of Flower Drum Song. Keye Luke called Wing Luke's 1965 death in an airplane accident "a great loss" (Skeer).

Master Po: His Favorite Role

Throughout the 1960s he continued to take on many television roles, appearing in I Spy, The Andy Griffith Show, General Hospital, Star Trek, The Big Valley, and Family Affair to name just a handful. He played everything from grandfathers to gangsters. In 1972, Luke became a series regular as Kralahome, the prime minister to the king of Siam played by Yul Brenner, in a CBS television series based on the play and the movie Anna and the King of Siam.

He also landed the role he later said was the favorite of his career. Kung Fu, which ran from 1972 to 1975, starred David Carradine as a Shaolin monk and martial arts master wandering the Old West -- a role many people felt should have gone to Bruce Lee. Luke played his mentor, Master Po, a blind sage who shares wisdom with his young protégé, whom he calls Grasshopper, in flashbacks. Luke wore opaque contact lenses for the role. Tiny holes drilled in the center allowed him limited vision as he moved around the set. Luke said he relished sharing nuggets of Chinese philosophy "from Confucius, from Mencius, and actually saying them in English for a world audience ... where do you get an opportunity like that?″ (Voorhees). Luke did reveal that some words of wisdom in the scripts also came from the Talmud.

A lifelong learner, Luke said the best part of the role was that it inspired him to study Chinese philosophy, partly to answer questions from young fans. Despite the rigors of two television series in the early 1970s, Luke continued to paint in oils. He was also studying Chinese calligraphy and Mandarin Chinese to add to the Cantonese he'd spoken since childhood. To keep his memory sharp, he memorized Shakespearean roles. And, decades after singing in Flower Drum Song, he was singing Mozart arias and German lieder to keep his voice in shape for the increasing amount of voice work he was doing.

In 1974, uncredited, he took part in Bruce Lee's Enter the Dragon by dubbing the voice of the film's villain because actor Kien Shih didn't speak English. He was a busy voice actor throughout the 1970s and 1980s, audible on the soundtracks of Scooby Doo, The Smurfs, Alvin and the Chipmunks and many more animated shows, as well as dubbed foreign films. He also continued to take television series roles including appearances on M.A.S.H., Magnum P.I., Falcon Crest, Miami Vice, the Golden Girls, The A-Team, and Charlie's Angels

He had a recurring role on Sidekicks, a martial arts series, and appeared in the 1984 film Gremlins as Mr. Wing, a grandfather who owns a Chinese curio shop. In 1990, he reprised his role as kindly Mr. Wing in Gremlins2. His final film appearance was in the 1991 Woody Allen film Alice. He gave a memorable performance as Dr. Yang, a bossy herbalist and hypnotist who provides a young New York matron with herbs and advice that render her invisible while she sorts out her unhappy life. Less than a month after its release, at the age of 86, Luke died of a stroke in Whittier, California, with his daughter Ethel Luke Longenecker, a social worker, at his side. He had lived with her and her family after the death of his wife.

At 81, in 1986, Luke was given the first Lifetime Achievement Award by the Association of Asian Pacific American Artists at a dinner at the Beverly Wilshire hotel. When interviewed about the honor, he told a Los Angeles Times reporter that he'd had a great career, and felt he'd been very lucky. But he also said "I never wanted to be an actor ... I wanted to draw" (Ong).

In 2015, his granddaughter donated his papers to the Margaret Herrick Library of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. The collection includes more than 25 linear feet of manuscripts and photographs, and 406 artworks including layouts, celebrity portraits, book illustrations, and personal artworks going back to his freshman year at Franklin High School in Seattle.