Charles McKay was among the earliest and most colorful of the U.S. settlers on San Juan Island, located in far northwest Washington between the mainland and Vancouver Island, Canada. After years of adventure in the gold fields of California and British Columbia, he arrived in 1859, immediately assumed an active role in local affairs, and continued to be a spirited participant in the island community throughout his long life. He told, with enormous pride, how he was the first to raise an American flag on the island in defiance of British threats and claims. He was one of three initial commissioners of San Juan County and helped establish the first island school and first church congregation (Presbyterian -- although he later became a dedicated Christian Scientist). McKay aided prosecution of an infamous murderer and supported incorporation of Friday Harbor (the only town on San Juan Island and the county seat). He advocated for woman suffrage and Friday Harbor's vote to prohibit liquor sales. A man of tall stature, strong constitution, and vivid personality, McKay was still undertaking heavy work every day in his blacksmith shop until weeks before his death at age 90.

Adventure and Arrival on San Juan Island

A child of Scottish immigrant parents, Charles McKay was born in Pictou, Nova Scotia, Canada in 1828. The family name was McCoy, and Charles didn't change the spelling until the 1880s, but for much of his life he was generally known by his contemporary islanders as Charles McKay. At the age of 16 he moved across the border to Maine and took up work in lumbering. After word of the California gold rush arrived in that distant state, McKay was determined to try his luck. He hoped to shorten the long sea voyage through the Strait of Magellan near the tip of South America by disembarking at Panama, making his way across the isthmus, and then picking up a ship on the other side to complete the voyage. However, plans went awry when McKay contracted yellow fever on the trip through Panama; he was ill for three months and didn't arrive in California until 1856. Like so many others, his success in the gold fields was limited but, undeterred, he moved on to British Columbia when gold was found in the Fraser River area in 1858. However, mining success eluded him there too. When, in 1859, he and his friend from Maine, Daniel Oakes (1831-1905) traveled from Westminster, B.C., to Victoria, they heard about San Juan Island (just east across Haro Strait) and its abundant game, good fishing, and fertile prairies for farming. When McKay later wrote a history of this time, he remembered, "So we went there to see it. There appeared to be a lodestone on the island, for we stuck there at once" (Washington Historical Quarterly, July 1908).

San Juan Island had few more than a dozen American settlers when McKay arrived. The British had claimed the island, and the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), whose regional headquarters were in Victoria, had established a large sheep and farming operation on the island. British settlers were encouraged; American settlers were considered interlopers. Tensions came to a head when a valuable HBC Berkshire hog invaded, not for the first time, the unfenced potato garden of Lyman Cutlar, an American settler who, in a moment of extreme exasperation, seized his gun and shot it. His offer to pay for the pig was rejected as insufficient, and the HBC manager threatened to have Cutlar detained and sent to Victoria for British justice. Just the mere threat guaranteed an indignant determination among the American settlers to demonstrate their independence from British control and allegiance to the U.S. Among the most determined and vocal was newly arrived Charles McKay.

The settlers decided that the fast approaching July 4, 1859, holiday offered the perfect opportunity for a celebration and reminder to the British of America's successful rebellion -- as the British termed it. McKay and another settler enthusiastically volunteered to row to the Washington mainland to procure the largest possible American flag, which would be raised on a tall, newly constructed pole as the centerpiece of the festivities. The event took place on the southeast end of the island (near today's Cattle Point) at the home of Paul Hubbs (1835-1910), who had been appointed by the Washington territorial government as Deputy Customs Inspector with the impossible task of collecting customs on British and any other imports to the island, also claimed by the U.S. The celebration was a resounding success and continued noisily on through the day and night. McKay was given the honor of raising the flag on its new pole.

"Much ammunition was expended, loud talk prevailed, bravado and drinking kept apace. During the day everyone [i.e. all 14 settlers] made at least one speech, and all declared their independence from Great Britain and Hudson Bay Company to the constant background of rounds fired, corks popped, and bottles emptied" (Crawford, 70-71).

For the rest of his life McKay would tell and retell the story of the flag raising. Each retelling seemed to include more dramatic details, and a history he wrote almost 50 years later offered a definitely more sensational narrative than the contemporary recollections of other participants. In later years he would also go on to note he had been the first civilian to send a telegram from the island (at a cost of $45) during the joint American-British military occupation (1859-1872) that soon followed the celebration, and that he thereby had been instrumental in the removal of an incompetent officer who had been put in charge of the U.S. military force on the island. Through the years his expanding story evolved into an increasingly splendid tale of his heroic contributions to the island's early history.

Becoming Part of a Growing Community

Three years after his arrival on the island, McKay again succumbed to the allure of possible gold-mining success when ore was found in the remote and rugged Cariboo Mountains region of northern British Columbia. Initially he went to work for a friend for the good wage of $16 per day, but he soon missed the island and returned before leaving again in 1864 for another attempt to make his fortune. He was back within a year. And by then he had even more to entice him back, as he now had a wife waiting for him to return.

Mary Josephine Enis (1845-1927) had been born in Nanaimo on Vancouver Island. Her father was a Frenchman from Montreal and her mother a Native American. It is probable that Mary considered herself among the Mitchell Bay Tribe, who lived primarily on the northwest side of San Juan Island. Mary McKay was a quiet, shy woman who throughout her life was rarely seen outside her home and almost never spoke to passers-by. Mary and Charles married in 1862, a union that lasted more than half a century, and through the next decades they had 11 children (six boys, five girls).

McKay had claimed a homestead and the couple soon settled into a life of farming. McKay even invested with neighbors in a thresher but soon sold his share. Together with other growing families the McKays recognized the need for a school for the island's children, and McKay was among the early subscribers who contributed financial assistance and labor to construct the first schoolhouse in 1865 and pay the teacher's salary. By 1867 McKay children were listed on the school roster, which included youngsters from British, French, Canadian, German, Native American, Kanaka (Hawaiian), and American families. In later years McKay served as chairman of the school-district board of directors. In addition to educational needs, the spiritual needs of islanders were also of concern and McKay, with other community leaders, established the first religious congregation on the island, also in 1865. The Presbyterian group met initially in the schoolhouse, but by 1878 construction had begun on a handsome church building in a beautiful setting overlooking the San Juan Valley near Madden's Corner (then site of a blacksmith shop) on today's Cattle Point Road.

The year 1873 was destined to be a significant one for McKay. In spring, he assisted with the investigation of a horrific double murder. Harry Dwyer (ca. 1839-1873), also originally from Nova Scotia, had purchased a homestead on San Juan Island. Like McKay and so many other early settlers, he had married a Native American woman, and the Dwyers were neighbors and friends of the McKays. Indeed, when Harry later fell in love with a young British woman in Victoria, his discarded (and pregnant) first wife found refuge with the McKays when she was displaced by the new bride. Selena Dwyer (ca. 1850-1873) had barely settled into her new home when she and Harry were brutally murdered. A local Kanaka boy, whom McKay also knew, was suspected of the crime and, when he fled to Victoria, McKay was among those who followed to aid the Victoria police in solving the crime. Ultimately it was McKay who persuaded the young man to confess to the killings and lead the authorities to valuables stolen from the victims. That fall McKay's testimony was vital in obtaining a guilty verdict when the prisoner was extradited for trial in a Washington territorial court.

That same autumn McKay was also called upon to assume a far different responsibility. The previous year residents of San Juan and neighboring islands had been relieved when the question whether the U.S. or Great Britain had sovereignty over them was finally resolved by mediator Kaiser Wilhelm I (1797-1888) of Germany in favor of the United States. The islands were then considered to be part of Washington Territory's Whatcom County. However, the ever-independent-minded islanders wanted to direct their own affairs, and on October 31, 1873, the territorial legislature created San Juan County. To organize and oversee the new county's government, the governor appointed three commissioners including Charles McKay, who was promptly elected chairman of the group. He went on to serve in that capacity for two additional terms.

A Person of Character and Conviction

By the 1890s Charles McKay was a well-known and well-liked member of the island community. Friends teased him about some of his self-proclaimed talents and accomplishments, among which was his ability to forecast the weather. So frequent were his firmly stated predictions that it was decided that some special recognition was needed. A group of islanders therefore composed an official document and sent it to U.S. President Benjamin Harrison (1833-1901). In it the petitioners solemnly recommended that McKay be appointed as chief of a national weather bureau and signal service because he had "by long observations and deep research, got the moon down fine and holds confidential and secret communications with the man in the moon, and knows beforehand all the dangerous atmospheric changes, such as cyclones, twisters, blizzards, hurricanes and typhoons" and could "compile and publish ... a weather diagnosis that will be reliable and invariably correct for all time to come" ("Chas. McKay Raised ..."). And the forecasts would be not just for the U.S. but for the entire world. It is not known what President Harrison thought of the proposal.

Never hesitant to voice his views, McKay frequently wrote letters to the local newspaper on a variety of topics on which he felt strongly. In 1891 he offered what was headlined "A Didactic Letter," a long discourse of his personal religious insights in which he argued the importance of following Biblical teachings in order to have a happy life. He sought to apply logical argument to religious belief, noting that Christ's "teaching was to love one another and do unto others as you would like others to do unto you, and he did all this teaching for 33 years without pay," thereby proving, McKay wrote, that Jesus was no ordinary man, for an ordinary man would not have done this or performed the miracles recorded in the Bible (The Islander, March 5, 1891). Five years later he was introduced to the work of Mary Baker Eddy, founder of Christian Science with teachings centered on a faith in the harmonious interrelation of science, theology, and medicine. He had found a spiritual belief system that fully matched and amplified his own, and for the rest of his life he practiced and enthusiastically promulgated the philosophy and teachings of Christian Science. Even many years later, newspaper letters were devoted to lively exchanges with detractors on his religious beliefs and life attitudes and actions that reflected Christian Science tenets and his strong convictions about what would assure a life of personal happiness and a disposition of goodwill toward others.

Although now an established community member in his late 60s, McKay was always on the lookout for new prospects in mining, and in the late 1890s he apparently gave up farming the homestead to again try his luck. He concentrated his efforts on the far side of the state, in the Northport area of Stevens County in Northeast Washington, approximately 100 miles north of Spokane and only eight miles from the Canadian border. He and others invested $9,000 developing five mines, two of which, the Wall Street and Aetna mines, had particular potential. On a trip back to the island in 1900, McKay visited the newspaper office in Friday Harbor and shared his experiences, which were then relayed in the next issue for the community to read. The editor added that "Mr. McKay feels very hopeful and thinks they have a very fine property. Let us hope they have as he has worked very hard and certainly deserves a good thing" ("Local and Personal").

A Friday Harbor Resident

At the start of the new century, McKay, at age 73, undertook some major changes in his life. After four years (of unknown success) in Eastern Washington, he and Mary and the youngest children were established in a home in Friday Harbor at the corner of First and East streets where today cars are parked awaiting the ferry. McKay set up a blacksmith shop just down the hill behind the house and soon was providing a much-needed service for local residents. In addition to that work, he also was frequently employed on county projects.

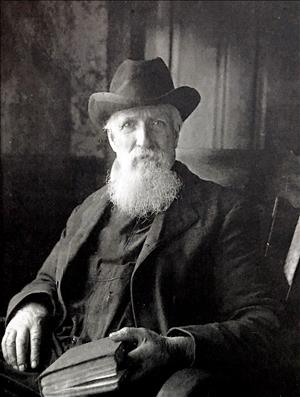

McKay's first years as a Friday Harbor resident brought new accolades. A special supplement to the local newspaper in 1901 included McKay and his blacksmith work. In 1906 he and fellow early settlers Edward Warbass (1825-1906), the first county auditor, and Stephen Boyce (1829-1909), the first county sheriff, were honored at the grand festivities of the cornerstone laying for the new county courthouse that was to be built between First and Second streets across from the Methodist church and next to the Friday Harbor schoolhouse on the hill just north of town. As a featured speaker, McKay once again told the story of the July 4, 1859, flag raising and his early efforts on behalf of the rights of Americans on the island. The three patriarchs, all in their 70s and with impressive white beards, were by then much-revered keepers of the island's past.

Perhaps inspired by preparations for his 1906 speech at the courthouse, McKay announced that same year (in a long front-page Friday Harbor Journal article illustrated with his portrait) that he was starting to write a history of those early days. "Why may the public not expect something of intense interest from so reliable a source as the pen of this veteran islander?" ("History of Early Settlement ..."). McKay's history, published in 1908 several years after it was written, was a decidedly dramatic and personal retelling, including a note from the author: "The writer is now seventy-seven years of age and is enjoying the fruits of running the risk of losing his life while opening up this country" (Washington Historical Quarterly, July 1908). He also, before closing, urged readers to learn about Christian Science as a guide for richer and happier lives. The publisher, too, added a note explaining to readers that McKay was respected throughout the islands and still hard at work as a blacksmith despite his advancing age.

During the same period, however, some decidedly less-positive episodes marred McKay's life. For decades the spring that bubbled up in the middle of eponymous Spring Street, the main road through Friday Harbor, regularly overflowed into a channel behind several of the town establishments and gradually had created a substantial gully that had could not be safely traversed and had become a dump for much of the garbage of some neighboring businesses. Friday Harbor was still unincorporated and therefore without a town government, so the county assumed responsibility for having a bridge built for travelers on First Street enabling them to cross the gully and continue south to their homes and businesses. The structure was a very basic construction of wood planks supported by logs; no railings or side guards were included. On a dark January night in 1906 McKay was on his way home from town when, feeling his way across the bridge, he stepped into a hole created by a short plank and fell from the bridge onto the rocks in the gully, dislocating his shoulder and causing other injuries.

The following year he wrote a testimonial in a Christian Science publication that his reliance on the teachings of the church and the assistance of a Christian Science practitioner had enabled the injuries to heal perfectly with minimal discomfort and that he was fully restored and back in the blacksmith shop, shoeing heavy horses. However, he was irate that the incident had happened at all. He sued the county for $5,000, claiming that he had been disabled for many weeks and unable to practice his trade because of negligence in the design and construction of the bridge. The county commissioners pointed out that McKay had been, himself, a commissioner when the bridge was originally built and therefore should have been very familiar with it and more careful in attempting to cross it. Nevertheless, they were willing to compromise with the eminent and elderly citizen, and the suit was settled for $750.

Then just a few years later, when McKay traveled by steamer to Seattle to view the popular Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition on the University of Washington campus, he was assaulted on the trip home when he surprised a sneak thief in his cabin. The culprit clearly had chosen the wrong passenger to rob, as McKay promptly aided in capturing and subduing the man, who was later identified as a crew member. McKay traveled to Seattle to testify at the trial, where the defendant was found guilty and sentenced to six months in jail. More than six feet tall, in remarkably good health, self-confident, and physically strong from years in the blacksmith shop, McKay (at age 80) was not to be overcome by a mere steamship waiter.

A Community Activist

McKay had long maintained a strong interest in whatever affected the town and its citizens, and was among those who, beginning in 1907, advocated for the incorporation of Friday Harbor as the first step to a better quality of life for the community. He signed petitions, endorsed the campaign in the newspapers, and celebrated when the incorporation measure finally passed in 1909. Although only men could vote at the time (women were not granted the vote in Washington state until November 1910), McKay very publicly supported woman suffrage, citing, among other arguments, the positive influence women had on community morals. In spring 1910 he added a strong voice urging citizens to vote to prohibit liquor sales and close the three saloons in Friday Harbor. He sent a lengthy letter to the paper, outlining the evils of liquor and its effects on wives, children, and the community, citing personal experience with a son and a nephew who had been ruined by alcohol. "O stop and think before you cast your vote," he implored, "and help to take temptation away from our weaker brothers" ("Earnest Appeal ..."). The vote for prohibition succeeded, and McKay was pleased; six months later he wrote another full-column letter to the paper extolling the positive effects of the new law and observing, "I never saw Friday Harbor as decent as it is now" ("How Local Option ...").

Although he had not held public office for many years, McKay decided to enter his name as a Republican candidate for the state legislature in 1912. The Friday Harbor Journal editor remarked that "he is a man capable of filling the office with credit, owing to his knowledge of public affairs" ("Two More Aspirants ..."), while the editor of the other local paper, the San Juan Islander, commented, from years of personal acquaintance, that "if elected, [he] will be anything but a passive member" ("Another Legislative ..."). McKay acknowledged that there might be questions concerning his age (83), but he urged doubters to stop by the blacksmith shop and watch him shoeing large horses with vigor and ease. He lost in the Republican primary; he did not capture the San Juan Island vote, which went to well-known local doctor and businessman Victor Capron (1868-1934), but, to his great satisfaction, he swept the vote of the rest of the county.

McKay's final years continued to be filled with activity. In 1915 he helped form the San Juan County Pioneer Association and enjoyed attending its gatherings and exchanging reminiscences with other settlers. That same year he and his daughter Charlotte (ca. 1889-?) were founding members of a small local Christian Science congregation that began meeting informally at the Odd Fellows Hall (now the Whale Museum) and other places around town before acquiring a church building on Guard Street eight years later. And, in 1917, he was invited to be the honored participant in a very special community ceremony. As islanders learned of America's entry into World War I, it was decided that prominently displaying a large U.S. flag on a tall pole in the center of Spring Street would be an appropriate patriotic gesture and, of course, there could be no one more fitting to be the first to raise it high than Charles McKay. One observer, a young woman at the time, noted that as the flag unfurled "an expression of impersonal pride spread over his face. It was the kind of look that made me feel proud too" (Reed, 125).

Charles McKay died on December 1, 1918, at the age of 90 years and two months. He had been active and vital almost to his last days. A writer half a century later described him as "another of those colorful pioneers who helped make the history of this corner of the country anything but dull" ("Chas. McKay Raised ..."). Earlier, the obituary published by regional newspapers on the mainland included a long statement penned by McKay himself noting his place in San Juan Island history. And a month after his death, an almost full-page, highly romanticized article about McKay appeared in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer relating again the story of the 1859 flag-raising and McKay, "the mighty leader of men," who "[stood] out for law and order on the island he helped hold for the United States" (Haight). McKay would have been very gratified.