Early Saturday morning, October 27, 1894, a fire in the West Street Hotel, located on the second floor of the Colman Block Annex, a commercial warehouse located at the foot Columbia Street in Seattle, kills 16 occupants and injures several others. Insurance adjusters estimate the damage to the building and its contents at approximately $17,725. The crude, wood-frame structure, built immediately after the Great Seattle Fire of 1889, will be replaced in 1898 by a fireproof building made of sandstone. The tragedy will goad the city council into enacting more stringent codes to prohibit the use of such venues as inexpensive rooming houses and eventually appointing a fire marshal to inspect all such buildings and enforce fire ordinances.

Rooming House, Firetrap

The West Street Hotel was in the Colman Block Annex, two buildings separated by a narrow alleyway fronting on West Street (now Western Avenue) between Marion and Columbia Streets. The buildings were conveniently located close to the Northern Pacific Railway station. The annex was owned by James M. Colman (1832-1906), one of Seattle's early capitalists. Constructed immediately after the Great Seattle Fire of 1889, they were two-story, wood-frame structures, clad in corrugated metal, and originally intended for large-scale, commercial and wholesale businesses.

In 1891, the south annex building was leased to William E. Stevens (1854-1930), who converted the entire second floor, approximately 12,000 square feet, into a rooming house by dividing the large storage spaces into 78, mostly windowless, 10-by-13 rooms. The interior partitions were constructed of pine boards which dried out and shrunk over time, leaving the walls with a multitude of gaps. There was one hallway, 4 feet wide, that ran the 125-foot length of the structure, and five 4-foot-wide hallways that traversed its 90-foot width with window openings at each end. There were originally three staircases leading to the second floor, but one on West Street had been removed to accommodate Charles G. Sanborn, the proprietor of a wholesale grocery store on the ground floor. This left only two exits, one on Columbia Street that led upstairs to the hotel office, and another at the northwest corner of the building on West Street. Firefighting equipment consisted of a large water tank and several buckets located on the roof, and a fire bucket, each holding five gallons of water, at the end of each hallway.

According to Stevens, Seattle Fire Chief Gardner Kellogg (1839-1918) and Seattle Superintendent of Buildings Levi F. Compton (1825-1894) had surveyed the rooming house in 1891 and deemed it acceptable since it met fire code for this class of building. Stevens called this firetrap the West Street House. In 1893, he sold the business to William F. Butler (1843-1917), who operated it as the West Street Hotel. Butler established the hotel office and a restaurant at the corner of Columbia Street and Post Avenue, with its kitchen facilities above on the second floor.

Pandemonium in the Night

At approximately 12:50 a.m., on Saturday, October 27, 1894, fire suddenly erupted inside the West Street Hotel. According to night clerk Spencer F. Butler, son of the proprietor, he had gone from the office to the kitchen upstairs to get some food. While there, he lit a kerosene lamp and then, hearing noise in the hotel office, went back downstairs, leaving the lamp burning in the kitchen. He was gone only a few minutes when he heard a muffled explosion and ran back upstairs to investigate. The lamp was on the floor in pieces and the kitchen was ablaze. Butler tried to smother the flames with a blanket, but it was already too late. The fire had climbed the walls, ignited the ceiling, and was spreading rapidly throughout the tinder-dry interior of the building. He immediately roused his father, William, and sisters, Margaret and Mabel, and then rushed down the narrow hallways banging on doors and shouting "fire." While exiting through the office, William Butler thought to save the hotel's register, which showed they had 19 regular lodgers and 28 registered overnight guests, which didn't include spouses and/or children.

The flames advanced so rapidly the hotel guests were taken by surprise, and there was pandemonium as men and women, in their night clothing, fled for their lives. Some of the occupants were fortunate enough to escape down the stairways while others were forced to retreat toward the window openings. Since the hotel had no fire escapes, the choices were to either climb down knotted-together bed sheets or jump 20 feet to the ground. While on his beat, Seattle Police Patrolman Frank E. Bryant (1862-1939) saw flames and smoke pouring from the second floor of the structure and triggered the fire-alarm call box at the corner of Columbia and Front Streets (now 1st Avenue). Patrolman Bryant and several bystanders then positioned themselves below the windows, attempting to help the terrified people trying to escape from the second story.

Futile Efforts to Halt the Blaze

Within minutes, firefighting equipment arrived from Seattle Fire Department Headquarters/Station No. 1 located at 6th Avenue and Columbia Street, just seven blocks away. More apparatus responded from downtown stations, and Captain Richard C. Connors moved the fireboat Snoqualmie from her slip at the foot of Madison Street to the north side of Colman Dock (now Pier 52), intending to keep the blaze from spreading to the waterfront. The hose-wagon from Station No. 5 at Madison Street and Railroad Avenue met the Snoqualmie at the dock, and its crew laid a hose line from the vessel, with her powerful water pump, to the scene of the fire. The hose, a relic from the Great Seattle Fire, was old and rotten and burst four times under pressure. The Snoqualmie was made to cease operations each time to allow firefighters time to replace the damaged sections, wasting critical minutes.

The flames spread quickly, and the entire structure was raging inferno before the fire apparatus arrived at the scene. Since entering the hotel was an impossibility, Seattle Fire Chief Albert B. Hunt (1862-1930) concentrated his efforts on preventing the blaze from spreading to the nearby buildings and piers. Seattle Police Chief Bolton Rogers (1859-1899) arrived at the scene with a squad of officers and cordoned off the area, keeping the large crowd of onlookers back and allowing firefighters space to work. At 2:45 a.m., Chief Hunt declared the fire "tapped out" and firefighters began searching through the smoldering ruins for bodies. They were joined by Rogers, King County Coroner Dr. George M. Horton (1865-1927) and a deputy coroner, James A. Greene. The remains of 16 victims were recovered from debris, most burned beyond recognition.

Meanwhile, the survivors of the conflagration huddled together on West Street waiting for help to arrive. Minor injuries were treated at the nearby Northern Pacific Railway station by Dr. Edward P. Heliker (1865-1928), who had been summoned by Police Chief Rogers. Those who sustained serious burns and broken bones in the chaotic retreat from the hotel were taken to Providence Hospital for medical attention.

At 3:45 a.m., Coroner Horton ordered a halt to the search and had the building cleared of all personnel. Seattle Police Captain George Hogle (1850-1928) had officers stationed on the block to ensure that nothing was stolen from the remains of the annex or any of the adjacent buildings, accessed to allow firefighters to stream water into the blaze from above.

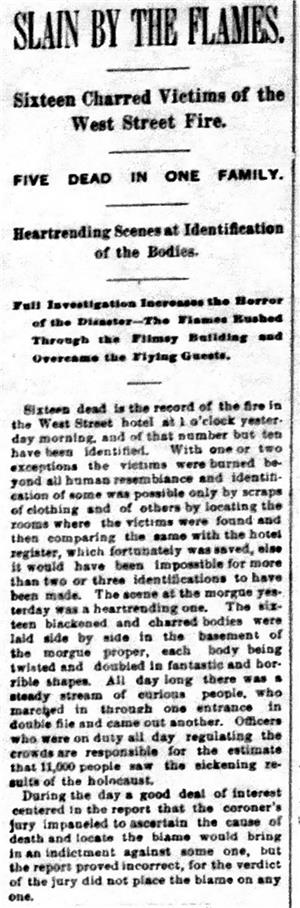

Charred Remains and an Immediate Inquest

Identification of the dead was accomplished by comparing the names of the survivors with those listed in the hotel's register. The guests were mostly transients, and no one at the hotel knew who they were or where they came from. The bodies were transported to the Bonney & Stewart Funeral Parlor, located at 3rd Avenue and Columbia Street, to await queries from acquaintances or relatives seeking missing kin. All day Saturday, a steady stream of curious spectators filed through the morgue in the basement of the mortuary to view the charred remains. Police officers, on duty to keep order, estimated that some 11,000 people showed up for the viewing on Saturday and almost as many on Sunday. The story of the tragedy, which listed the names and descriptions of the victims, appeared in newspapers throughout the country. Within a few days, all but one of the casualties had been positively identified and the remains either buried in Seattle cemeteries or shipped to relations elsewhere.

On Saturday afternoon, Coroner Horton held an inquest at the King County Courthouse at 7th Avenue and Alder Street. Numerous witnesses were called to testify including Fire Chief Hunt and other departmental officers who described their firefighting efforts and searching through the rubble for victims. William F. Butler, the hotel proprietor, testified concerning the building's construction, and his son, Spencer, on duty as the night clerk, described how the fire started and his efforts to rouse the guests and evacuate the premises. Patrolman Bryant, who sent in the fire alarm, told of his efforts to help those attempting to escape from the burning hotel. Other witnesses described how they narrowly escaped death fleeing from the inferno.

The coroner's jury deliberated for an hour before returning the verdict early Saturday evening. Predictably, they found the victims died as the result of an accidental fire in the kitchen of the West Street Hotel which was caused by the explosion of a kerosene lamp. The jurors went on to say, however, that: "We are of the opinion that such buildings are totally unfit for lodging purposes and would recommend that proper steps be taken to prevent the recurrence of such a disaster" ("Slain by the Flames").

After the Inferno

On Monday, October 29, 1894, the Seattle City Council passed a resolution designed to prevent disaster in other such buildings. The resolution, submitted by 8th Ward Alderman Harry R. Clise (1860-1919), instructed Superintendent of Buildings John W. Van Brocklin (1837-1900): "To submit such amendments to the existing building ordinances as will compel all hotels, lodging houses, factories, etc., to provide fire escapes from all floors above the first; that all halls and passage ways be of such width as will permit free entrance and exit, and that all such passage ways shall have an outside opening, and to incorporate such other measures as he may deem best" ("A Move to Stop …").

However, not much was done to enforce new fire-safety ordinances for several years. Finally, in February 1901, Seattle Mayor Thomas J. Hume (1847-1904) appointed Fire Chief Gardner Kellogg, a strong advocate of fire prevention, as the city's first Fire Marshal, which was immediately confirmed by unanimous vote of the city council. Finally, there was someone in city government with the specific authority to inspect all buildings for code violations and enforce the fire ordinances.

Insurance adjusters estimated the damage to the south building of the Colman Block Annex and its contents at $17,725. The building was quickly repaired and once again housed large-scale, commercial and wholesale businesses. In 1897 both annex buildings were razed and replaced by two, three-story buildings made of sandstone, costing approximately $100,000. In 1904, the Colman Building, fronting on 1st Avenue, was renovated and four stories were added to that structure. A fourth story was also added to the Colman Building Annex, fronting on Western Avenue. In 1906, the Imperial Candy Company leased the entire annex building to manufacture its signature product, "Societe Candies." The company used that venue to manufacture chocolates and hard candies until August 1973 when the factory moved to Bellevue. The structure, known as the Society Candy Building, was demolished in the spring of 1976 to make way for the construction of an office/apartment building, but that didn't happen. The vacant space became a parking lot and remained so until 2012, when a 16-story apartment/condominium building, named The Post at Pier 52, was constructed on the site.

The following are listed in the Seattle Death Registers Index 1881-1907 as having died of asphyxiation in the West Street Hotel fire on October 27, 1894:

John F. Anderson

Alden G. Butler (1830-1894), age 65

Frederick Bollman

I. F. Clark

Allie Huffman Hancher (1867-1894), age 27

Amy Hancher (1893-1894), age 18 months

Erma Hancher (1889-1894), age 6

Pearl Hancher (1891-1894), age 4

Eliza Jay Huffman (1845-1894), age 50

William Mattison

Angus McDonald

Matthew McSorley

Andrew J. Otterson (1876-1894), age 18

Louise Otterson (1834-1894), age 60

Unidentified adult male

Chester F. Wilson