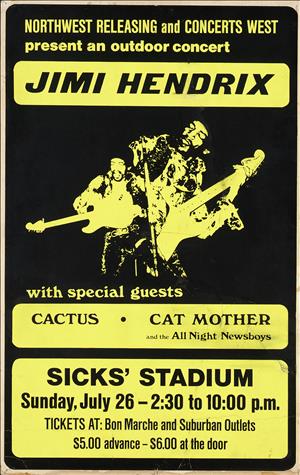

On the afternoon of July 26, 1970, Jimi Hendrix (1942-1970) headlines a concert at Seattle's venerable outdoor ballpark, Sicks' Stadium. The all-day festival is billed as a "Concert on the Ground," but the ground itself is muddy because of rain, a Seattle hazard even in late July. Writes The Seattle Times the next day, "The outfield grass was a soggy mat and the infield dirt a giant mud pie. Yet a fair-sized crowd braved Seattle's fickle precipitation and huddled on the field and in the puddled stands to watch Jim Hendrix perform" ("Wet Crowd Catches ..."). Hendrix died less than two months later.

Experience Required

The Jimi Hendrix Experience's 1970 tour of the U.S. would later be referred to as the Cry of Love tour, a reference to the band's fourth, and in-the-works, album titled The Cry of Love. The band had come a long way since exploding on the world stage in late 1966. It had scored radio hits, produced three timeless psychedelic-era rock albums -- Are You Experienced, Axis: Bold As Love, and Electric Ladyland -- and blown away the audience at 1967's Monterey International Pop Festival in California. The band had toured as widely and steadily as any of its rock 'n' roll peers and was recognized as one of the era's best.

But along the way, bassist Noel Redding (1945-2003) had quit the band, and then Hendrix and drummer Mitch Mitchell (1946-2008) brought aboard several other players, including bassist Billy Cox (b. 1939), and performed as Gypsy Sun & Rainbows at the Woodstock Festival in New York on August 18, 1969. Following that, Hendrix and Cox brought on drummer Buddy Miles (1947-2008), forming a new group, Band of Gypsys, whose eponymous album was released in the U.S. on March 25, 1970. The following day saw the theater debut of the Woodstock movie, and then the Woodstock: Music from the Original Soundtrack and More triple-album set was released on May 27, 1970. Hendrix' stunning performance nailed down his skyrocketing reputation as the world's finest rock guitarist.

In The Ballpark

In his two most recent Seattle shows, Hendrix had played the Seattle Center Coliseum. This time he would perform outdoors, a business decision by Seattle-based promoter Concerts West. According to the head of Concerts West, young people were just beginning to enjoy outdoor rock festivals and concerts, and Sicks' Stadium allowed for greater ticket sales. Hendrix was familiar with the ballpark. It had been the home for the Rainiers baseball team -- who were named after owner Emil Sick's main business, the Rainier Brewing company -- and like many Seattle kids of his era, Hendrix loved to go there to watch ballgames. The stadium had also been the site of Elvis Presley's Seattle debut on September 1, 1957 – a show that a teenaged Hendrix and his boyhood pals had been lucky enough to attend.

By 1970, the Rainiers were long gone -- as were the Seattle Pilots, a major league team that played just one season before moving to Milwaukee. The ballpark was now in the middle of the outdoor festival era and became the site for a few rock 'n' roll concerts, including one on July 5, 1970, featuring Janis Joplin, the Youngbloods, Pacific Gas & Electric, and the Steve Miller Band.

Concert on the Ground

The plan to hold a marathon concert -- scheduled from 2:30 p.m. to 10 p.m. -- featuring three bands on what would likely be a bright sunny day must have seemed like a good one at the time. But. Seattle. Rain.

One of the three bands promoted on the concert's poster was Cat Mother and the All Night Newsboys. They had formed in New York, played a lot at Café Wha? -- where a pre-fame Hendrix had gigged in 1966 -- and signed a management deal with Hendrix's manager, Michael Jeffrey, who got them a record contract with Polydor Records. Hendrix produced both their 1969 Top-40 hit single "Good Old Rock 'n' Roll" and their The Street Giveth and the Street Taketh Away album.

The second band advertised was Cactus, formed in 1969 by Tim Bogert (bass) and Carmine Appice (drums), who had been with Vanilla Fudge when that group toured with Hendrix in 1968. The other member was Jim McCarty (guitar), who'd played with the Buddy Miles Express.

The show was planned and co-promoted by Concerts West -- a Seattle company fronted by Pat O'Day that had been handling Hendrix'a U.S. tours since 1968 -- in collaboration with another Seattle firm, the Northwest Releasing Corporation. The latter had been formed by entrepreneurs Zollie Volchuck and Jack Engerman in 1953 to distribute films to theaters. Also involved was Boyd Grafmyre (d. 2019), a hippie generation concert promoter who had long booked shows at Seattle's Eagles Auditorium and produced the fabled Seattle Pop Festival at Gold Creek Park in Woodinville in 1969. Grafmyre served as the Sicks' Stadium show's organizer and presenter. He also rustled up a local band at the last minute to fill in when Cat Mother couldn't make it for reasons unknown. The Seattle band was Rube Tubin & the Rondonnas and included veteran rockers Billy Scream (vocals), Larry "Rube Tubin" Richstein (guitar), Buck Ormsby (bass), and Russ Kammerer (drums).

Grafmyre hired a crew to help with the show, including Anthony "Tiny Tony" Smith (1940-1987), a founding member of Seattle's 1950s hit-making doo-wop group, the Gallahads. After the Gallahads, Smith fronted Tiny Tony & the Statics, a combo that happened to have been one of young Hendrix's favorites in 1960-1961. But it was now a decade later, and, "At this particular time," Smith recalled, "I was working for Boyd Grafmyre as a part of personnel, security, and I was assigned the job of staying with [Hendrix]. And I can remember some real cool instances. Some heavy things. See, Jimi had the idea that every time he came to Seattle it jinxed him in some kinda way. I can remember a couple times he came to the Coliseum, the same thing happened. Thunderstorms and thunder and lightning. And stuff broke" (Smith interview with author).

Rainy Day, Dream Away

The morning of July 26 dawned with promising sunshine, and the star and his father Al Hendrix (1919-2002) celebrated with a bit of daydrinking. But any hopes for afternoon sun were dashed. "The outfield grass was a soggy mat," The Seattle Times reported, "and the infield dirt a giant mud pie. Yet a fair-sized crowd braved Seattle's fickle precipitation and huddled on the field and in the puddled stands to watch Jim Hendrix perform ... The well-prepared brought large plastic sheets to sit on, small tents to shield their heads. Ingenious spectators wore ponchos made from giant garbage bags. But many were ill-clothed and barefoot. And the day was cold" ("Wet Crowd Catches ...").

The concert began with Rube Tubin & the Rondonnas, followed by Cactus and intermittent showers. There was a pause of more than an hour between Cactus and the start of Hendrix's set. "The wait seemed endless, yet the stubborn Hendrix fans refused to give up. Few left. When Hendrix did appear, the crowd rose to its feet and surged towards the tarpaulin-covered stage. Dressed in flaming colors, Hendrix spoke to the crowd. He seemed somewhat ill at ease, perhaps put off by the chill and drizzle -- and understandable reaction" ("Wet Crowd Catches ...").

That Hendrix had spent much of the day at his father's home, where they'd gotten into an argument, helps explain the star's foul mood, which he couldn't seem to shake. When his band went onstage at 7:15 p.m., Hendrix kicked things off by addressing the crowd, saying, "I want you to forget about yesterday and tomorrow, and just make our own little world here." Gazing out at his damp audience, he added: "You don't sound very happy, you don't look very happy, but we'll see if we can paint some faces around here" (Cross, 302).

With that intro, he, Mitchell (drums) and Cox (bass) kicked off with the song "Fire." As the song ended, a fan playfully tossed a pillow up on the stage, annoying Hendrix. "Oh, please don't throw anything up here. Please don't do that, because I feel like getting on somebody's head anyway. Fuck you, whoever put up the pillow" (Cross, 302). Hendrix booted the pillow back into the crowd, and flipped them off while confessing that he'd had a few scotches. Midway through their second song, "Message to Love," a dispirited Hendrix ambled off the stage, leaving Mitchell to improvise a drum solo as the rain pelted down. "It was a tough day because of the weather," O'Day said. "But that's one of the hazards of an outdoor concert in Seattle. At any time, but particularly at that time, late in the summer. But, Jimi didn't do badly. You know, he got his licks in" (O'Day interview with author).

Jimi's Jinx

"At Sicks' Stadium the only shelter there was on the stage," Tiny Tony Smith recalled, "and when the rain started doin' its thing, only the real stalwart fans stayed right up there. The rest of the people ran to the bleachers which was way along from where the stage was set up over in left field. And Jimi was disappointed in that, 'cause I guess he figured that should have had the power to keep the people there, but the people were drenched. And, in fact, some of them left. Period" (Smith interview with author).

Continued Smith: "I can remember Jimi being so disappointed, and he walked off the stage in disgust. And so, I asked Boyd: 'What am I supposed to do?' And he said 'Just follow him.' Well, at this time they had those little trailers set up around the back there, and he went -- and gotta little help from one of his vials. And I guess that psyched him up. And when he went back the people were still there waitin' for him to come back on, and this time when he came out he got out from underneath the tarp. Out there in the rain on the edge of the stage. Everybody says 'No Jimi! 'Yer gonna get electrocuted. All this rain is gonna short out 'yer amps, and 'yer gonna get hurt!' And he was sayin' 'No. No. No.' He's gotta get out there and do that. It was like he had to prove something. But what I didn't know was that he was living precariously at that time. He was takin' all these chances. He was livin' on the edge of his life. I guess after you get to be so big, that's the only thing left. But what happened was: he got out there and started doin' that screamin' guitar bit. And what he was tryin' to accomplish did happen: several hundreds of people came out there to get close to him just 'cause he was doin' his thing" (Smith interview with author). And the songs continued:

- "Lover Man"

- "Freedom"

- "Sunshine Of Your Love"

- "Red House"

- "Foxy Lady"

- "Machine Gun"

- "The Star-Spangled Banner"

- "Purple Haze"

- "Hear My Train a Comin'" / "Keep On Groovin'"

- "Voodoo Child (Slight Return)"

- "Hey Baby (New Rising Sun)"

Love or Confusion

The Seattle Times' review allowed that "Hendrix played well, as usual. The spark and fire of his music were there, dampened only slightly by the rain. ... Mitch Mitchell, did some remarkable percussive work. But unfortunately, the amplifiers were poorly balanced and it was difficult to hear the bas player. Shortly after Hendrix began, another downpour pelted the crowd, scattering the unprotected to the stands. The acoustics in the grandstand proper never were intended for rock concerts, and the overwhelming echo added some confusion to the sound ... Perhaps in the future it would be wise to revert to the practice of the bygone – but not forgotten – days when baseball was the main attraction in Sick's Stadium: Call off the concert due to rain" ("Wet Crowd Catches ...").

Smith said Hendrix fumed backstage about his ongoing family problems, that he'd been feuding again with his father. Hendrix said he was going stay and spend the night in the trailer parked at the stadium, though he did in the end return to the family home to spend the dwindling hours of final visit to Seattle. In the wee small hours Hendrix, a cousin, and a couple of family friends jumped into a car and spent a few hours cruising Seattle, checking on some of his old boyhood haunts including Harborview Hospital, where he was born; the Yesler Terrace housing project, Garfield High School, and one of his family's former homes on Yesler Way. They took a backroads route all the way around Lake Washington.

The following morning, the band flew off to Hawaii for shows on Maui on July 30 and Oahu on August 1, its final U.S. shows before returning to England. On August 26, Historic Performances Recorded at the Monterey International Pop Festival was released, the album showcasing Hendrix's unique artistry. He died in London three weeks later at age 27, on September 18, 1970.