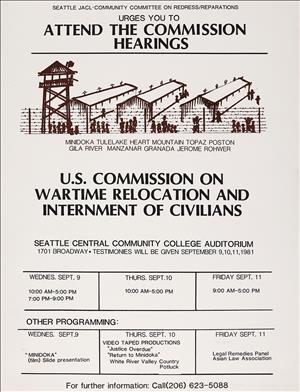

On September 9-11, 1981, close to 160 people testify in front of the federally appointed, nine-member Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) about the impact of Japanese American incarceration during World War II. Testimonials come from Japanese American incarcerees and their descendants, public officials, community members, veterans, and native Japanese speakers. Participants arrive from Alaska, Hawai'i, Oregon, and Washington. For many former incarcerees, it is one of the first times they have spoken publicly about the trauma of their wartime incarceration.

A Longer, Larger Process

Though the Seattle hearings were a watershed for the public and for the local Japanese American community, they were also part of a much longer, larger process in the fight for reparations. Seattle activists had taken their cues from leaders such as Shosuke Sasaki (1921-2002) and Henry Miyatake (1929-2014). After a national call in 1970 by the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) for volunteers to study redress proposals, Miyatake and Sasaki formed the Seattle Evacuation Redress Committee (SERC) in 1973. The team included Miyatake, Sasaki, Mike Nakata (1917-2004), Chuck Kato (b. 1932), and Ken Nakano. Their team developed the "Seattle Plan" in 1973, which was "the first concrete strategy for redress" and included demanding individual payment as part of reparations (Niiya).

Their work formed part of the foundation for the first Day of Remembrance at Camp Harmony in Puyallup in 1978, which in turn laid further groundwork for redress proceedings. SERC members worked with congressman Mike Lowry (1939-2017) to put forward HR 5977, which asked for individual reparations for all who were incarcerated during World War II. Early drafts of this first Congressional call for reparations included Aleuts, Japanese Americans, German Americans, and Italian Americans. However, Seattle area activists experienced a temporary setback when Japanese American politicians did not support HR 5977 (feeling it would not be politically prudent) and Lowry's bill failed in 1980. Instead, Congress passed HR 4399, backed by the national JACL, to establish a commission to study and report on the long-term effects of incarceration.

The Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) was established in July 1980 in order to determine if wrong had been committed against Japanese Americans who were incarcerated in concentration camps during World War II. Establishing the CWRIC was thus the result of a decade-long struggle between several segments of the Japanese American community.

Mock Hearing: May 1981

Thanks to efforts by local activists and journalists, the Seattle-area community had begun to prepare for the hearings as early as December 1980. Workshops ran until May 1981, with activists such as Karen Sekiguchi and seasoned journalist Frank Abe preparing the community for questions. As attorney Gerald Sato later pointed out in the Rafu Shimpo, the Southern California Japanese American newspaper, the "Seattle Nikkei community had kept redress in front of their community for ten years" (quoted in Shimabukuro 71).

Organized by the Community Committee on Redress/Reparations (CCRR), a mock public hearing took place on May 23, 1981, a Saturday, from 12:30 p.m. to 5 p.m. About 200 people attended at the Nisei Veterans Hall. The CCRR included representatives from area Japanese American religious organizations, and four local chapters of the Japanese American Citizens League. Seattle JACL chapter redress chair Cherry Kinoshita (1923-2008) and Gordon Hirabayashi (1923-2012) co-chaired the event.

At the mock hearing, organizers distributed the results of a questionnaire that asked local Japanese American institutions and organizations if they were in favor of redress. SERC had also developed and administered a survey, which it sent to some 9,000 community members in local organizations. The survey asked respondents what form of redress they preferred, and if they would be willing to provide testimony at hearings. The survey indicated a broad base of support for redress from respondents.

The mock hearings were complete with a moderator (Dr. Charles Z. Smith [1927-2016]) and commissioners played by judge Ron Mamiya (1949-2019), attorney Douglas Jewett (b.1946), and State Sen. Ruthe Ridder (b. 1929). A commissioner from the CWRIC, Hugh B. Mitchell (1907-1996), also attended. One of the attorneys for the Fred Korematsu case, Dale Minami (b. 1946), also happened to be in town and attended the mock hearing.

For many participants, it was the first opportunity to speak about their experience publicly. It was noted how emotional the events were. Many presented versions of their previous submitted written testimonies, though a few presented dramatic and emotional departures from their written material.

Three Days of Testimony

By the time the official CWRIC hearings took place more than three months later in the Seattle Central Community College auditorium, Seattle redress organizers had gathered a powerful array of volunteer speakers prepared to speak for 5 minutes each, usually in panels of five per session. The auditorium was frequently filled to capacity with approximately 300 persons in attendance.

The hearings opened with statements from public officials including Seattle Mayor Charles Royer (b. 1939) and the Honorable Art Wang (b. 1949). Former incarcerees, including Jim Akutsu (1920-1998) and Theresa Takayoshi (1918-1984) from Seattle and Homer Yasui (b. 1924) from Portland spoke about the psychological impact of discrimination and economic loss from their wartime experiences. Several panels of Japanese Americans veterans were included. Various proposals for redress were covered by attorneys and organizers from the Japanese American community. Panels covered the economic losses and impact for Japanese Americans, while others covered the impact for populations such as Japanese Peruvians and the Aleuts.

The Seattle hearings brought controversy. Chinese American writer Frank Chin testified about the culpability of the JACL's wartime leaders with the mass eviction efforts, which created some pushback from past leaders such as Mike Masaoka and the JACL's national newspaper, the Pacific Citizen. Out of the 160 speakers over three days, only five opposed the redress efforts. They were met with boos and angry calls from the audience.

Nevertheless, the local organizers built a solid case. As hearings participant and journalist Robert Shimabukuro later noted in his book Born in Seattle, "Everything in Seattle had run on time, nobody had demanded more time to speak, and nobody had broken down in the middle of giving testimony" (71). While perhaps less dramatic than hearings in other cities, the Seattle sessions ran smoothly.

Moving Toward the Civil Liberties Act

The CWRIC public hearings had begun in Washington, D.C., in July 1981 and ran through late September. Organizers heard from close to 750 participants. Hearings were scheduled in Washington, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, and Chicago, in addition to three places in Alaska: Anchorage, Unalaska, and St. Paul. The Seattle hearings occurred close to the middle of the process.

The Seattle hearings remained an important component of the redress process. The Commission published its findings in December 1982 under the title Personal Justice Denied. The commission's conclusions found that mass incarceration was caused by "race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership" ("Personal Justice Denied"). The national struggle for Japanese American reparations would continue for another six years before President Ronald Reagan (1911-2004) signed the 1988 Civil Liberties Act. The act included a written public apology from President George H. W. Bush (1924-2018), established a public education fund, and granted $20,000 for each individual incarcerated, intended as reparation for mass injustice and violation of Japanese American civil rights.