Murray Morgan (1916-2000) was one of the Pacific Northwest's most beloved historians. A native Tacoman, he wrote the indispensable Skid Road: An Informal Portrait of Seattle and several other books about the region. In the following reminiscence written in the 1960s and shared with HistoryLink by his daughter, Lane Morgan, Murray writes about the night he was unable to raise the Eleventh Street Bridge in Tacoma. It's a favorite family story, Lane Morgan said, made more poignant when the Eleventh Street Bridge was officially renamed the Murray Morgan Bridge in 1997.

'The 2,100-foot Steel Monster'

In this land of lovely bridges the one that means the most to me is over-aged, squat and misshapen -- one of those Prides of the Past that has become a Bottleneck to Progress -- the Eleventh Street Bridge in Tacoma. It connects the downtown business district with the industrial tideflats.

The Eleventh Street Bridge became a Tacoma necessity when the St. Paul and Tacoma Lumber Company in 1889 built its first mill on the abundantly available but until then undesirable bogland across the waterway from the city: until then the flats had been used mainly as a parking lot for Indian burial canoes. The bridge was one of those necessities, however, that a town long lives without. It wasn't built for almost a quarter century.

Herbert Hunt, the local historian, reports that the bridge was dedicated "amid the squabblings over imaginary misdeeds that usually accompany large municipal enterprises." Everything about the Eleventh Street Bridge inspired argument and oratory. Labor long demanded it, then voiced unhappy suspicions that business was benefiting too much when at last it was built. Armchair engineers disputed the design, some insisting that it be a new-fangled jackknife affair, others holding out for the traditional counterweight lift. Some said it should be wider, some double-decked. Aesthetes found it "ugly, hump-backed and fishtailed," damaging to Tacoma's impression, the pre-Madison Avenue word for image.

It was built, anyway, and dedicated on February 15, 1913, which makes it three years and a day older than I, but as it was part of the furniture of my childhood, I grew up with the false impression that The Bridge, like The Mountain, had always been there. This was only one of the many mistaken ideas I had about the 2,100-foot steel monster.

My father, who was a minister, often lectured in Seattle. As a youngster I would go with him on the boat, either the Tacoma or the Indianapolis, which left every hour on the hour for Seattle from the Municipal Dock under the Eleventh Street Bridge and made better, more beautiful and far less odiferous time than the buses do today. Through some wild misassociation with what must have been a sermon topic, I was long convinced that the bridge was named "The League of the Larger Life."

I was disabused of this notion one New Year's Eve when the newsboys came by our house yelling Extra. A loaded streetcar had rammed through the lowered gates and plunged over the gap left by the 200-foot lift section which had been raised to let a ship pass.

'Only an Idiot Could Foul Up'

Such were my memories of The Bridge when, not long after getting out of the Army, I applied for a job as relief bridgetender on the Eleventh Street. At the time I was teaching in a small college at a salary which made moonlighting attractive if not imperative. A friend, Wilmot Ragsdale, poet, philosopher, relief bridgetender and former colleague of mine on Time, had told me that the City of Tacoma had openings on the graveyard shift.

I was interviewed and hired by Joe Smith, the chief bridgetender, a conscientious but desperate public servant who was reduced to hiring poets and assistant professors because the mechanically able were not tempted by the pay scale for relief work.

Mr. Smith showed me how to close the barrier gates to traffic and operate the machinery that shifts the balance on the counterweights to raise or lower the 800-ton lift span. As a mechanical illiterate and motor moron, uneasy when changing tires or typewriter ribbons, I took careful notes on the process. I was not entirely put at ease by Mr. Smith's reassurance that "only an idiot could foul up on this bridge." His exception was noted.

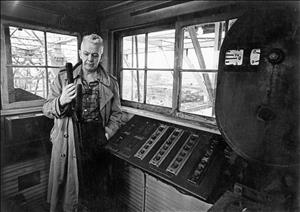

My first nights on the Bridge were uneasy. I'd arrive just before midnight, climb the catwalk to the tender's shack which sits on a platform above the road, and say Hello-Goodbye to the operator going off duty. Then I'd wait nervously for a summons to action. But as weeks went by and no boats signalled for me to get the span out of their path, I relaxed and settled down to grading papers and working on my own writing. The bridge was an ideal office, quiet, isolated, free from interruptions.

The serpent in my Eden was a fellow relief man who let me in on the bridgetenders' trade secret. He told me there were no boats. While the two other bridges along Eleventh had frequent business, our bridge was intensively idle. The mills up the waterway had long since burned down. The remaining factories required no ships tall enough to demand lifting the span.

"Then what are we dong here?"

"There's still a law on the books that says if you put a bridge over navigable waters you must be ready to remove the obstruction at the command of any vessels that come along."

So it was that my work habits changed. I brought to work not a typewriter but a sleeping bag and air mattress; I arrived at my nine o'clock class at the college more refreshed and less prepared. And so it was, too, that on a foggy Saturday night when a boat did blow for the bridge I was deep in the sack.

A Whistle in the Dark

I awoke to the sound of the boat whistling and looked out the window of the cabin. It was foggy, but dimly down the waterway I could see the lights on the mast of an approaching ship. I blew the whistle acknowledging receipt of the boat's command and went down the catwalk to the operating room, halfway between the platform and the roadbed on the outboard side of the bridge. I took with me the notes I had written on Joe Smith's lecture on how to raise the bridge.

1. I turned on the sirens and lights. At the first blink of red and howl of siren the headlights of the approaching cars slowed. In a moment cars at stopped at each end of the bridge. I felt a surge of power.

2. I pushed the button to close the gates. Nothing happened. I pushed again. Still nothing.

Perhaps the main power switch in the watchman's hut was open. I ran up to see, stubbing my bare toe painfully on the iron storm sill of the cabin door. The switch was closed. I looked out the window toward the approaching ship. It was still a long way off.

I blew the signal for him to stop.

Back came the signal for me to raise the bridge. He was coming through. I remembered being told, "When you're on this bridge you're in command--except when the master of a boat wants through, Congress says you've got to get the bridge out of his way."

I ran back to the control room and tried the switch again for the gates. Still no response. I looked at the line of stopped cars at each end of the bridge and thought, momentarily, about raising the bridge even with the gates down. Then I remembered the boys yelling Extra when the transit bus had plunged off the bridge years before. That was out.

But the cars had stopped and that gave me an idea. I grabbed a pair of flashlights, scurried down to the roadbed, and raced to the nearest car. A young man was wrapped around a girl. I tapped on the window and he looked up.

"Pardon. I'm the bridgetender and I can't close the gates and I'm not supposed to raise the bridge until I close them. Would you mind standing out here and flagging down any car that tries to come past?"

"Huh?"

I repeated it.

"You mean you can't raise the bridge until the gates are down and you can't close the gates?"

"That's it."

"Thanks," he said, gunned the motor, and Vroom! off he went across the open bridge.

I went to the next car. A thin young man was alone in it. "I'm a deputy sheriff," I told him. "Take this flashlight and flag down any cars that try to come by."

"Yes, sir," he said, taking the light.

I started to run to the opposite side but as I hit the metal mesh on the roadbed of the lift section I slipped and fell. The flashlight shattered.

As I picked myself up the boat whistled again.

I felt panic. Then I had another idea. I ran back up the steps to the cabin, stubbing my toe again on the storm sill. I dialed operator and asked for the police station. She rang. A woman answered.

"This is the Eleventh Street Bridge," I panted.

"Oh, quit your kidding," and she hung up.

I asked the operator again for the police station, got it, and said, "I'm the operator on the Eleventh Street Bridge. This is an emergency; I need two prowl cars right away."

"Yes, sir," she said.

Ex-Bridgetender

I looked out the window to see where the boat was. No boat. I looked out the other window. No boat. I went out on deck and looked in both directions. No boat. Then I heard something below and looked down. Through the grill I could see the lights of the boat passing beneath.

It was a tug and had not needed the bridge raised.

I sighed and I cursed and I went down and turned off the lights and sirens. I went back up to the cabin and wondered how I would ever write this on the morning report. And as I sat, the sirens began to wail again.

"Oh my God, a short circuit," I thought, and started for the control room. But as I got out on the deck, a stampede of cops came running up the catwalk from the deck, their guns drawn.

And the lead cop said, "It's all right, mac. We got that crazy son of a bitch with the flashlight."

A few weeks later Congress passed a special act putting the Eleventh Street Bridge on a stand-by basis. A skipper must give four hours notice if he wants it raised. After that I retired from bridgetending and things became dull.