On January 1, 1979, after nearly four years in Alburquerque, New Mexico, Bill Gates (b. 1955) and Paul Allen (1953-2018) move their fledgling computer-software company to Bellevue. The move returns the Lakeside School graduates to their native Seattle area and triggers a success story of staggering proportions. With fewer than 15 employees, Microsoft leases offices in the Old Bank Building in downtown Bellevue. The following year, it will move to an office park near Highway 520. By 1987 Microsoft will be housed in its new Redmond campus, with more than 1,800 employees and $345 million in annual sales.

Dawn of the Personal Computer

Before it became a juggernaut in Redmond, Microsoft consisted of a handful of college-aged computer zealots trying to harness the coming computer revolution from a strip mall in a dusty patch of New Mexico. Their saga began in 1975 with the first personal computer -- the Altair 8800, developed by Micro Instrumentation and Telemetry Systems (MITS) of Albuquerque. Introduced on the cover of the January 1975 issue of Popular Electronics magazine, the Altair was revolutionary -- both small enough and cheap enough for home use. It sold for $397 in kit form and could fit on a desktop. Before MITS began shipping the Altair in February 1975, the smallest computer on the market had been "a $35,000 mini that filled the better part of a small office" ("Today's Breakthroughs …").

While warmly received by hobbyists, the Altair was primitive, lacking an easy-to-use programming language. When assembled, the machine was "a plain rectangle of gray metal that came equipped with a microprocessor, a jury-rigged input-output circuit and a full 256 (not 256K, but 256) bytes of memory -- barely enough to store one short paragraph. There was no operating system, no off-the-shelf software. Niceties like a keyboard and a monitor were still under development. To load in data, you flipped a bunch of switches on the front of the box. The answers came out in a row of blinking red lights representing binary numbers" ("Today's Breakthroughs …").

In Cambridge, Massachusetts, Bill Gates and Paul Allen read the Popular Electronics story with excitement, and soon Gates, a 19-year-old sophomore at Harvard, was on the phone with MITS founder Ed Roberts, telling Roberts that he and Allen, a 21-year-old programmer for Honeywell in Boston, could develop a language for the Altair. Gates said they would write a version of BASIC -- a plain-English programming language developed in 1964 at Dartmouth College -- and hand deliver it to Albuquerque. Roberts already had fielded offers and was reluctant. Gates was customarily undeterred. "There was no doubt in my mind we could write a BASIC. I was fairly self-confident in those days," he recalled. "We didn't know how long it would take us, and it was kind of funny because we were sort of acting like we had it already. We went to work, day and night" ("Bill Gates Interview").

Eight weeks later, Allen flew to Albuquerque with the completed language. At MITS headquarters in a strip mall next to a massage parlor, he loaded the paper tape into an Altair and began a demonstration. "He typed in a program, 'Print 2 + 2,' and it worked," Gates recalled. "He had it print out squares, sums and things like that. He and Roberts, the head of this company, sat there and they were amazed that this thing worked. Paul was amazed that our part had worked, and Ed was amazed that his hardware worked, and here it was doing something even useful. And Paul called me up and it was very, very exciting. Pretty quickly we decided that we ought to get out there and really help these guys get their act together" ("Bill Gates Interview").

Setting up in Albuquerque

Allen was destined to spend the next four years in Albuquerque. After the demonstration for Roberts, MITS hired him as vice-president of software; he moved to Albuquerque in the spring, and Gates joined him from Harvard that summer. In addition to completing a licensing agreement with MITS, the young men formalized their own business arrangement. As founded on April 4, 1975, Micro-Soft (the hyphen was later dropped) would be owned solely by Gates and Allen, but not equally: The agreement gave 60 percent of the company to Gates, 40 percent to Allen. "Bill made an argument that I was getting a salary while he was still at Harvard making no money. I could see the logic of that," Allen recalled. "Maybe I could have argued more forcefully for the value of my original idea, but at the time I agreed to it" ("Paul Allen: 'I Think Bill ...'").

Allen settled in at the Sundowner, a motor lodge along Route 66 a few blocks from MITS headquarters in the Cal Linn Building. He frequented the café at Duran Central Pharmacy, where his favorite order was a Hatch-green-chili enchilada and a tamale with red chili sauce. Gates, who divided his time between Harvard and Albuquerque until January 1977, had appetites for fast food, fast cars, and the orange drink mix Tang. Of his time in Albuquerque, Gates recalled: "I bought one thing that was a tiny bit of a splurge, which was that my first car that I owned was a Porsche 911. It was used, but it was an incredible car ... Sometimes when I would want to think at night, I'd just go out and drive around at high speed and fortunately I didn't kill myself doing that" ("Bill Gates Discusses …").

Albuquerque police nabbed Gates on one of his moonlight rides and brought him to jail. His mugshot would become part of Microsoft lore. When Time magazine's Walter Isaacson went looking for "the real Bill Gates" in 1997, he reported that Gates "got three speeding tickets -- two from the same cop who was trailing him -- just on the drive from Albuquerque the weekend he moved Microsoft to Seattle. Later, he bought a Porsche 930 Turbo he called the 'rocket,' then a Mercedes, a Jaguar XJ6, a $60,000 Carrera Cabriolet 964, a $380,000 Porsche 959 that ended up impounded in a customs shed because it couldn't meet import emission standards, and a Ferrari 348 that became known as the 'dune buggy' after he spun it into the sand" ("In Search Of …").

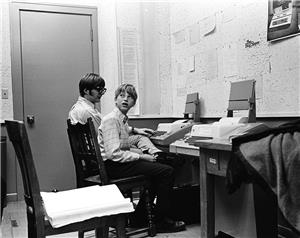

For initial help at Microsoft, Gates and Allen recruited friends. Monte Davidoff, who helped author the original Altair BASIC at Harvard with Gates and Allen, spent two summers in Albuquerque. Ric Weiland, one of Allen's pals from the computer lab at Lakeside School in Seattle, took time off from his studies at Stanford to help (he later became a fulltime employee). Chris Larson, another Lakeside computer whiz, came down for the summer of 1975. Lakeside alum Marc McDonald signed on in 1976; he was Microsoft's first salaried employee. To accommodate its growing crew, Microsoft rented space in the Cal Linn Building next door to MITS. It was here that Gates became famous for sleeping on the floor of his office. In the fall of 1976, Microsoft moved to rented space on the eighth floor of a bank building near the Albuquerque airport, where it remained until the final days of 1978.

In their agreement with MITS, Gates and Allen granted MITS a license to bundle BASIC with its computers in return for royalties on every copy delivered. The deal was not open-ended; Gates and Allen could receive a total of no more than $180,000. In addition, MITS secured the rights to license Altair BASIC to other computer makers and split the profits with Gates and Allen. Crucially, the contract contained language that MITS would give its "best efforts" in selling BASIC to other companies.

A Split From MITS

By the time Gates moved to Albuquerque fulltime in January 1977, Microsoft's relationship with MITS had soured. MITS assumed an adversarial position, trying to keep BASIC exclusive to the Altair, while Gates sought to sell languages to as many computer makers as possible. Finally, "On April 20, 1977, after consulting with Gates' father in Seattle, and hiring an attorney in Albuquerque, Gates and Allen notified Roberts by letter that they were terminating the licensing agreement for BASIC, effective in ten days. They cited several reasons: MITS had failed to account for thousands of dollars in royalty payments, failed to make its 'best efforts' to promote and commercialize BASIC, and failed to secure secrecy agreements when BASIC was licensed to certain third parties, mostly hobbyists" (Hard Drive, 114). As specified in the contract between Microsoft and MITS, the dispute went to binding arbitration. Microsoft prevailed. Gates and Allen were now free to market BASIC to all sectors of the rapidly growing computer industry.

The break with MITS greased Microsoft's exit from New Mexico. By 1978 the company had grown to 12 employees and only one, technical writer Andrea Lewis, was from Albuquerque. Recruiting engineers to New Mexico was proving difficult. Ultimately, Allen concluded, "We had no customers in Albuquerque" ("Erring Is Human …"). In March 1978, the staff received a memo announcing that Microsoft would be moving to Seattle at the end of the year. "It took a while for me to sell the idea to everybody," Gates said. "Albuquerque has its advantages ... But everybody was very involved in what they were doing, and there was the excitement behind where we were going. So, I was able to get literally everyone but my secretary, Miriam Lubow, to come up with us. And that became the core group" ("Bill Gates Interview").

That winter Microsoft's employees packed up and made their way to the Pacific Northwest, Gates blasting north in his Porsche 911. No real effort was made by the city to keep Microsoft in Albuquerque, a blind spot some civic leaders would regret. For Gates and Allen, the move was well timed. "We really had completed all the languages we wanted to do, and most of our eight-bit software work," Gates said. "So, as we were moving up to Seattle … a lot of resource was already focused on 8086 development software -- we just saw that as the coming thing. Moving to Seattle let us expand our personnel quite a bit, and that's when spreadsheet development started, that's when Microsoft Word started. We hired a number of key people" ("Bill Gates Interview").

Moving to Bellevue

Microsoft's first year in Bellevue was quiet. The company settled into leased office space on the eighth floor of the downtown Old Bank Building at 10800 NE 8th Street. Gates had his finger in every pie. "When we got up to 30 [employees], it was still just me, a secretary, and 28 programmers," he recalled. "I wrote all the checks, answered the mail, took the phone calls -- it was a great research and development group, nothing more. Then I brought in Steve Ballmer, who knew a lot about business and not much about computers" (Hard Drive, 163).

When Ballmer signed on in June 1980, Microsoft was still in the Old Bank Building. It soon moved to an office park at 10700 Northrup Way, convenient to Highway 520 and a Burgermaster restaurant "that was basically the company's cafeteria" ("Hamburger Expert Bill Gates …").

The move to the Northrup location was barely a mile but not without complications. "At the time, the company was still very small, and the task of managing the relocation was shared among all the employees," wrote Raymond Chen, a company historian. "After everybody settled in at the new building, it became apparent that the mail volume was barely a trickle. In particular, checks were not coming in … In the excitement of moving, nobody remembered to file a change of address form with the Post Office. A visit to the old Bellevue offices revealed a huge mound of mail at the old location. A change of address was quickly filed, but in the meantime, Steve Ballmer became the company mailman. Every day, he would drive to the old offices, pick up the mail that had accumulated, dump it in the trunk of his car, then deliver it to the Northrup offices" ("From Microsoft's Mail Room …").

Ballmer's primary task was hiring. Some of the recruiting was done the old-fashioned way, with classified ads in local newspapers. The word "Microsoft" appeared in The Seattle Times for the first time on October 10, 1979, predating Ballmer, in a help-wanted ad: "COMPUTER System Programmer. Full time. Position involves designing, debugging & maintaining compiler, interpreters & operating systems for micro-processors. Requires BS or MS in computer science plus at least 2 yrs directly related experience. Company paid health insurance. Salary $18,000. Send resume to: Microsoft, 10800 NE 8th St, Suite 819, Bellevue, WA, 98004."

A March 23, 1980, classified in the Times sought a system programmer, as well as a technical support person to "interface with our customers by telephone & mail." Ballmer arrived two months later. On September 21, 1980, he took out a large display ad with a persuasive sales pitch. After listing the many benefits of working for Microsoft and living in the Pacific Northwest – "mountains, ocean, desert, rain forest, rivers and lakes all within easy reach" -- the ad concluded: "We are looking for outstanding systems programmers -- those with intelligence, drive, and a commitment to excellence. We want programmers who will advance The Standard in microcomputer software. Applications may be made only by resume, attention Mr. Steve Ballmer, Assistant to the President."

As eager new faces appeared, many of the original Albuquerque employees fell away. A married couple, programmer Steve Wood and bookkeeper Marla Wood, quit in 1980, and Marla Wood later sued Microsoft for sexual discrimination (a settlement was reached). Programmer Bob Greenberg, the impetus behind an iconic group portrait of the original Albuquerque employees in December 1978, departed in 1981. Andrea Lewis, the only Albuquerquean, left in 1983 to become a journalist and fiction writer, and later became part-owner of Hugo House in Seattle. Production manager Bob Wallace quit in 1983, as did Paul Allen, shortly after being diagnosed with Hodgkin's lymphoma.

In 1984 Marc McDonald, Microsoft's first salaried employee, left to work on one of Allen's new ventures. Project manager Jim Lane departed in 1985. The two who stayed longest -- chief mathematician Bob O'Rear and programmer Gordon Letwin -- left in 1993. For some, including McDonald, Microsoft got too big. Others chafed at long hours and runaway expectations. Said O'Rear: "When we moved from Albuquerque to Bellevue, that's when the race seemed to start, because there seemed to be a lot more momentum in the microcomputer industry. It started to feel competitive" ("Idea Man …").

Meanwhile, in New Mexico, the 12-person firm was little missed -- at least until April 16, 1984, when Gates appeared on the cover of Time magazine and the accompanying story noted that Microsoft was sizzling, and Gates alone was worth more than $100 million. For the Albuquerque law firm of Poole, Tinnin & Martin, which did extensive legal work for Microsoft during its 1977 squabble with MITS, it was a reminder of lost opportunity. "They wanted to give us some stock in exchange for their legal bill, and we turned them down," partner Robert Tinnin Jr. recalled ("Erring Is Human …"). In addition, reported The Business Journals, "Tinnin says the consequences of his firm's decision have become a local legend, and it only grew in stature when his late partner, Paull Mines, missed a second shot at a Microsoft fortune -- when he declined the company's offer to relocate with it and become its in-house counsel" ("Erring Is Human …").

Few remnants of Microsoft remained. In October 2000, one of Paul Allen's companies purchased the Cal Linn Building -- then occupied by an East Indian grocery, barber shop, bead store, and office furniture liquidator -- for a reported $950,000. The sellers were told of plans for a computer museum on the site. Six years later, a permanent exhibit did open in Albuquerque -- but it was a 15-minute drive from the Cal Linn property. Housed in the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science and organized by Allen's Vulcan, Inc., the exhibit featured artifacts from Allen's fateful meeting with Ed Roberts in 1975, including "a yellowed roll of punch paper, scribbled over with illegible comments. It turns out to be the original copy of ALTAIR BASIC, the programming language that was Microsoft's first successful product. Rotating in a glass display, the ALTAIR 8800 itself sits like a block of masonry, as cyclopean as the buildings of Lovecraft's abyssal cities" ("A Visit …").

Postscript

Microsoft's growth accelerated in the first two years following the move from Albuquerque, though Seattle's newspapers remained largely oblivious to the rumblings east of Lake Washington. It was July 1981 when the first story about Microsoft appeared, a Seattle Post-Intelligencer feature by business writer Al Watts. Microsoft now had 95 employees, Watts wrote, and was expecting to finish the year with revenue of about $16 million. "With their company growing by leaps and bounds -- sales have doubled each year and in the last two months the workforce has more than doubled -- the two men are often in their offices for 16 to 18 hours a day" (Interfacing …").

Watts observed that Gates, then 26, had "loads of pent-up untapped energy" while Allen "comes across as cooler, more button-downed ... I guess you could call me the doer, and Paul the idea man," Gates said of their working relationship. "I'm more aggressive and crazily competitive, the front man in running the business day-to-day, while Paul keeps us out front in research and development" ("Interfacing …"). Gates told of plans to move into new, larger quarters in the fall of 1981, and predicted annual sales would reach $100 million in five years. He spoke of a coming revolution in the way ordinary people would interact with computers, and suggested Microsoft would be at the vanguard. "[We're] pushing the state of the art," Gates said. "Everyone is moving in the computer industry, but we're moving a little faster" (Interfacing …").