On Sunday June 27, 1926 at 4 p.m., the Alaska Steamship Company ship SS Victoria ties up at Pier 2 in Seattle. Unlike most arrivals from Nome, Alaska, the ship is accompanied down Puget Sound by a flotilla of private yachts sailing alongside and Army airplanes overhead. City dignitaries and a crowd of more than 5,000 are waiting at the pier. All are eager to see famed explorers and expedition leaders Norwegian Captain Roald Amundsen (1872-1928) and American Lincoln Ellsworth (1880-1951), and the commander and designer of the airship Norge, Italian Colonel Umberto Nobile (1885-1978). They had just completed the first airship flight over the North Pole from Spitsbergen, Norway to Teller, Alaska.

Amundsen's Second Visit of '26

This was Amundsen's second visit to Seattle in four months. In February 1926 he finished his cross-country lecture tour in the city. It was the Golden Age of Polar Exploration and he was well known in the Norwegian communities around Puget Sound. On February 21, Amundsen lectured to an audience of 3,000 at Seattle's Eagles Auditorium. On February 23, he lectured in Everett at the Everett Armory to a capacity audience of 1,500. In his presentation, he described his unsuccessful 1925 airplane flight attempt from Spitsbergen, Norway, to the North Pole. Amundsen expressed doubt that polar exploration by airplane would ever be successful, but that semi-rigid dirigibles such as the airship Norge held promise for success.

Originally scheduled to continue through March 17, Amundsen's 1926 lecture tour ended in Everett on February 23 when he received word that the Norge would soon be ready for their planned flight over the North Pole. On February 25, Amundsen left for the East Coast, where he joined Lincoln Ellsworth. From there the two traveled to Spitsbergen, Norway to prepare for the flight of the Norge over the North Pole.

Race to the North Pole

When they reached the Norwegian settlement at King's Bay, Spitsbergen, Amundsen and Ellsworth waited for the arrival of Umberto Nobile and the Norge from Italy, where the Norge had been built.

On April 28, 1926, Richard Byrd arrived at King's Bay with his Ford Trimotor airplane and his full expedition ready to be the first to fly over the North Pole. He was funded by exclusive news service agreements that would be of value only if he were the first to reach the North Pole by air. If he were not first, he would be left seriously in debt.

The Norge with Nobile, his Italian crew, and the Norwegian crew he picked up on the way from Rome, arrived at King's Bay later than planned. While Nobile and the Italians were dressed in polar clothing, the Norwegian crew was dressed in street clothing unsuitable for the cold temperatures. They had been instructed by Nobile to leave their warm clothing behind to save weight on the flight and were uncomfortably cold on the flight to King's Bay. Amundsen took this as a personal insult from Nobile. To further anger Amundsen, Nobile informed him that one of the airship motors would require repairs, delaying their departure to the North Pole for at least two days.

On May 8, while Amundsen and the Norge crew waited for completion of repairs, Byrd and his pilot Floyd Bennett (1890-1928) took off on a 15-1/2-hour flight north. On their return Byrd announced that he and Bennett had reached the North Pole and circled it for 13 minutes. But they returned at least an hour sooner than expected, a suspiciously shorter flight than distance and airplane speed would suggest.

North Pole Flight of the Airship Norge

Two days later, with repairs complete, the Norge was ready for flight. It departed at 9:50 a.m. on May 11 in clear weather. The airship reached the North Pole at 1:30 a.m. on May 12. At the pole, national flags were dropped, first the Norwegian, then the American, then the Italian. As instructed by Nobile to save weight, the American and Norwegian flags were handkerchief-sized flags, but the Italians dropped "an armload" of flags and pennants, one as large as a tablecloth.

Once past the pole, they flew on for 72 hours and 3,000 miles, landing at the small settlement of Teller, Alaska. Due to winds and weather, their landing place was 90 miles from their planned landing at Nome, Alaska.

The Norge's crew had hoped to determine whether there was land between the North Pole and the north coast of Alaska, but the airship encountered fog on most of its path. The determination would be made instead by the 1926 to 1928 airplane flights of Captain George Hubert Wilkins (later Sir Hubert Wilkins) (1888-1958) and Lt. Carl Ben Eielson (1897-1929). They found that there was no land in the area, only sea ice. They landed on the ice at several locations and Wilkins measured ocean depth below the ice.

At the completion of the Norge flight, Amundsen, Ellsworth, Nobile and some of the crew traveled from Teller to Nome to wait for the steamship SS Victoria for passage to Seattle. The Victoria arrived in Nome on June 12.

While the facts would not be known until about 70 years later, review of a Byrd diary and notes from his pilot Floyd Bennett confirmed suspicions that in fact, the Byrd flight of May 1926 did not reach the North Pole, falling short by more than 100 miles. Therefore, the Norge was the first in history to fly over the North Pole.

The Cruise to Seattle

The SS Victoria, the "Old Vic" as she was generally called, left Nome and headed south on June 16 for the 11-day trip to Seattle. In his book, First Crossing of the Polar Sea, Amundsen described it as a very old boat but built of the best materials and still "solid and strong" with first-rate updated passenger quarters completed only two years before.

This was the first return trip of the season from Nome to Seattle. Amundsen wrote that passengers on the season's first trip north and last trip south were a quite different group than the usual travelers carried most of the season. These sailings carried prospectors to Alaska to search for gold. Signs from the cruise to Nome were still posted throughout the ship reminding passengers to remove their boots before going to bed and that gambling was strictly forbidden (despite the presence of folding gambling tables in every cabin.)

While the Norge expedition had achieved the goal of crossing over the North Pole, Amundsen worried that they might meet a disappointing reception in Seattle. Was he expected to make a spectacular arrival by airship, not by steamship?

Amundsen's concerns about the warmth of the reception were quickly dispelled when they reached Port Townsend. There they were met by Seattle Chamber of Commerce representatives who joined them onboard for the rest of the trip. An hour before arrival, they were greeted by five Army airplanes flying overhead. About 20 miles from their destination, they were met by a flotilla of yachts and the steamship SS Atlanta that was chartered by the Seattle Italian community to greet Nobile and his Italian crew with songs and cheers.

In Amundsen's words from First Crossing of the Polar Sea:

"On the 27th of June we came down into Puget Sound, that wonderful arm of the sea that leads into Seattle Washington. Having passed Port Townsend, we should no longer be kept in doubt as to the attitude of the American People towards our flight. Deputations from the Chamber of Commerce and other public institutions met us here and laid before us the many and great preparations that had been made for our arrival. Shortly afterwards one aeroplane after another whizzed over the old Vic and gave us clearly to understand that here the cold had vanished. It was an unforgettable moment when we lay to at the Alaska Steamship Company pier in Seattle. Huge crowds were collected to welcome us" (Amundsen Ellsworth, 160-161).

Celebrations in Seattle

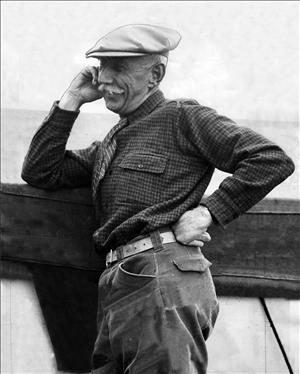

When the Vic reached Pier 2 at the foot of Yesler Way, the explorers were greeted by a crowd of 5,000 cheering people. As they were leaving the ship, Nobile appeared dressed in his finest blue military uniform, but Amundsen and Ellsworth were dressed like prospectors in clothing they bought in Nome. It was confusing to a young girl carrying congratulatory flowers who brought them to impressively dressed Nobile in his bright uniform rather than to Amundsen, the leader of the expedition.

Nobile had told the Norwegians not to bring unnecessary clothing onboard due to weight restrictions but did not impose the restriction on himself or the Italian crew members. When Amundsen saw Nobile and crew sharply dressed in their uniforms that they had kept hidden onboard the airship, he decided not to make an issue of it, although, if the airship had gone down because it was overweight and he had to walk over ice and snow to civilization as a result, it would have been a different story.

From the pier, the crowd formed a parade through downtown led by the Seattle Police Band up to the Olympic Hotel, where the guests spent the night. The explorers rode in luxurious automobiles. At noon on the following day, Monday June 28, they were honored at a luncheon in the banquet hall of the Chamber of Commerce building. A total of 800 tickets were sold to the public, filling the room to capacity. Overflow crowds filled adjoining smaller dining rooms, loungerooms, the main lobby area, and the corridors.

Amundsen, Ellsworth, and Nobile gave brief speeches. Amundsen said that the success of their flight proved the feasibility of reducing travel time and distance between continents with an Arctic lane for commercial travel by airship over the pole from Europe to America or Asia. On a personal note, he said that with this expedition, having now been to both poles, he had achieved his final long-sought goal and was ready to pass the future work off to a younger generation. He was 55; this would be his last expedition. He might even get married.

Ellsworth said he looked forward to more expeditions into the polar regions. Nobile said that exploration of the North Pole by airship was just beginning, and when he returned to Italy, he would present his plans to Premier Benito Mussolini (1883-1945). Nobile said that they would be sponsored by the Italian Government, not by the Norwegian Aero Club, and other than that, he could not divulge more details. After the luncheon, the explorers returned to their hotel to prepare for their departure by train.

Great Northern Railway Oriental Express

They left Seattle by train on the evening of June 28. Amundsen needed to reach New York by July 3, in time for the sailing of the Norwegian American Line ocean liner SS Bergensfjord for their return to Europe. To arrive on time, they could not extend their stay in Seattle. They chose to travel on the Great Northern Railway Oriental Express, as it had the reputation as the most comfortable train across the country. The railway had put a private car on the train for their use, with bedrooms, a drawing room, and their own private dining room. Amundsen described their mode of living as having changed from that of vagabonds to that of princes.

He likened their three-day journey across America to a triumphant procession, receiving congratulatory telegrams and being greeted by warm and enthusiastic crowds at their stops along the way. He was particularly delighted that the well-wishers were not just his fellow Norwegians but represented a cross section of Americans.

When they arrived at New York's Grand Central Station, Amundsen, Ellsworth, and the Norwegian crew were again greeted as heroes and driven by a police-escorted cavalcade through New York, cheered by enthusiastic crowds. They were honored at a public luncheon before boarding their steamship to Bergen, Norway. They received a similar reception in Bergen when they arrived on July 12 and again in Oslo, Norway, a few days later. After spending several months in Norway writing his account of the expedition, First Flight Over the Polar Sea, Amundsen returned to the United States in November 1926 for a lecture tour. Here he found that newly promoted General Nobile, under the direction of Mussolini, was conducting a 13-city U.S. lecture tour telling his own version of the expedition.

Two Years Later

From the beginning, there had been friction between Nobile and Amundsen. Amundsen and Ellsworth were leaders of the expedition, Amundsen for originating and organizing it and Ellsworth for his aid in financing. The Norwegian Aero Club that sponsored the trip purchased the airship from Italy and Mussolini. Nobile and the Italian crew were hired to pilot and operate it. Nobile insisted he should be an expedition leader also, but instead was given the title of airship commander. His contract prohibited him from providing accounts of the expedition to news services because they would violate the exclusive agreements that Amundsen had made to finance the expedition. But Nobile violated the contract and provided his own accounts to news agencies and in lectures. He also had delayed departure from King's Bay and imposed weight restrictions on all but his own crew. By the end of the expedition, the relationship between Amundsen and Nobile was strained and grew worse in the months that followed as their feud escalated in the press.

In June 1928, Nobile led his own flight over the North Pole in the airship Italia. He wanted to prove that he could be successful without the help of Amundsen and the Norwegians for the glory of Italy and Mussolini. They successfully reached the North Pole from King's Bay but crashed on their return. When he heard of the accident, Amundsen immediately left his home in Oslo on a French search plane to rescue Nobile and his crew, but the airplane was lost on the flight from Tromso, Norway, to King's Bay and was never found. Amundsen's retirement was short lived. Nobile and surviving crewmembers were eventually found and rescued, but his reputation was tarnished.