On December 6, 2012, a solo exhibition of the work of Richard V. Correll (1904-1990) opens at the University of Washington Libraries. Correll's legacy of art and papers has recently been donated by his daughter to the Labor Archives of Washington, part of UW Libraries Special Collections. A master printmaker, Correll is perhaps best known for his powerful linoleum cuts, woodblock prints, and etchings on themes of social justice, poverty, labor, and civil rights, many of them produced in Seattle during the Great Depression while he was working for the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Northwest subjects, ranging from Paul Bunyan to landscapes, quiet portraits of struggle, and searing cartoons, dominated this important period of his artistic development. During that time he developed his mature style, which Correll himself characterized as a synthesis of humanitarian realism and abstract, dramatic design. He continued to meld his work as an artist and his commitment to political activism throughout his career, inspiring many artists of the next generation.

Art and Social Conscience Nurtured

Richard Correll, known to family and friends as "Dick," was a gentle, unassuming man. In contrast, much of his art is forceful, stark, and frequently haunting -- primarily black and white images or prints with a single additional color, often expressions of his lifelong commitment to social and political causes. Dramatic balance between positive and negative spaces with crisp lines, textural shading, and bold forms characterizes much of Correll's work, which is represented in major art collections throughout the country including the Smithsonian's Renwick Gallery, Art Institute of Chicago, Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, the Library of Congress, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Portland Art Museum, Oakland Museum of California, and Seattle Art Museum. And his work is regularly included in Depression-era and graphic-arts exhibitions. In 2020, two Correll prints, Milltown School Child (1939) and Paul and Babe (1938), were included in the Tacoma Art Museum's major exhibition Forgotten Stories: Northwest Public Art of the 1930s.

Both Correll's artistic talent and his strong social conscience were fostered from his earliest years. His childhood was spent in small towns and on farms in Oregon and California where he developed a lifelong interest in animals, gardening, and the rural environment, and learned how difficult life was for so many who worked the land. His father worked as a lawyer, teacher, farm manager, carpenter, cabinet maker, and furniture-store owner while his mother had studied music at Oberlin College and encouraged Dick in his first arts endeavors. Both parents had strong views on issues of social justice and the government's obligation to provide opportunities and assistance for working men and women. Both also had a strong work ethic, and all of these influences were fundamental to Correll's life and art.

When Correll was in his teens, the family moved to Los Angeles where his father joined an uncle in constructing houses during a building boom. Correll had wanted to pursue a degree in art but was only able to take a few courses in ceramics and architectural drafting, the latter useful in his work in the family business, before the stock market crash of 1929 and subsequent collapse of the construction industry. The Corrells lost their savings and Richard's hopes of attending art school vanished. As he and his father joined so many others in the struggle to find work and support the family, Correll's social and political convictions increasingly aligned with the new left-leaning newspapers and magazines agitating for governmental action to help the desperate populace. Illustrations in these publications by artists such as Louis Lozowick (1892-1973) and Hugh Gellert (1892-1985) may have been Correll's introduction to powerful social commentary and criticism through strong, spare visuals. In 1933 he, his father, and uncle moved back to Oregon. Correll studied art from books borrowed from the public library and experimented with drawing, composition, and creating compelling visual messages. He submitted his first political cartoons to New Masses, a magazine featuring leftwing political commentary, literary content, and prints and cartoons on political themes. His uncle urged him to submit work to Voice of Action, a new radical labor publication in Seattle that supported the Communist party.

Woodcuts and Hunger Marches

In 1934 Correll and his father moved to Seattle. Correll worked as a freelance commercial artist while also designing handouts, banners, and signs supporting a variety of social and political causes. He joined the Sign and Picture Painters Union and became increasingly involved with Voice of Action. While he was drawn to much Communist Party ideology, he never became a member, instead promoting its activities as (in a contemporary descriptive phrase) a "fellow traveler," one who endorsed many of its tenets without formally joining the party. Voice of Action criticized Franklin D. Roosevelt's (1882-1945) New Deal programs from the left for not reaching those in most need. The newspaper was published weekly, selling for two cents an issue or $1.10 for an annual subscription. It was directed to trade unionists, the unemployed and organizations serving them, and political liberals. All its artwork and printing were done by volunteers; the printshop was donated as well.

Because using metal plates for creating images was too costly, Correll began instead to prepare woodblocks for printing his illustrations and cartoons. The process involved creating a design in reverse on a block of wood and then carving away areas of the block not part of the design. The resulting images were simplified and the messaging strengthened. Correll regularly provided illustrations and cartoons for Voice of Action and his woodblock prints became so popular that he advertised classes in woodcut technique in the publication.

Among his most important work for Voice of Action was the Northwest Labor History Calendar it published for 1936. Each month's page was illustrated with a woodcut, and brief accompanying text listed events of that month from recent labor history. The woodblock print for March, for example, illustrated the hunger march on Olympia in March 1933, an event that garnered remarkably little coverage in major Washington newspapers but was a prime impetus for the establishment of Voice of Action. The caption for the illustration indicated that this was the first hunger march. However, two months earlier, in January 1933, more than 1,000 unemployed workers and family members had marched to the state capitol to present demands for relief to the legislature. They asked for an appropriation of $2 million for immediate relief for rural families, weekly cash benefits of $10 for each unemployed worker and an additional $3 per dependent. To pay for this, they proposed sharply increased taxes on all timber "held by corporations or trusts," on "all capital and property accumulations in excess of $35,000," and on all income of more than $3,000 per year ("1,000 Jobless ..."). None of the requests or proposals was taken up by the legislature.

Another group of 3,500 men and women representing 114 workers' organizations then arrived in Olympia in March. Correll's illustration of the event presented the point of view of a participant moving forward near the front of the marchers but encountering a crowd blocking the way, many armed menacingly with rifles. Remembering the participants surging into the city during the January event, city and Thurston County authorities, who had been expecting up to 5,000 participants, were prepared this time. The marchers were met at the Olympia city limits and escorted to a public campground where they were kept under guard from the time they arrived until the following day when they were ordered to leave Olympia. The sheriff and police department had sworn in an additional 50 deputies who, together with about 200 local vigilantes (also deputized), surrounded the camp, allowing no one in or out "unless they could show proper motives" ("Vigilantes ..."). Plans for a parade from downtown to the capitol were scrapped.

Not all officials were entirely unsympathetic. Olympia Mayor Earl N. Steele (1881-1968) had urged those planning the march to stay home as he was concerned the city wouldn't be able to handle the crowd. "It is hard to see people go without food or shelter and to see them unable to go home because of lack of gasoline, even if they have brought the condition voluntarily on themselves" ("'Hunger Marchers' Worry"). However, several Washington papers quoted in The Seattle Times were much more critical. The Brewster Herald dismissed the march as "nothing more nor less than a Communist move" and the Everett Herald huffed "today is the time to show that the vast majority of the people of the state disapprove of these organized 'marches'" ("That 'Hunger' March"). Correll's dramatic illustration is an important visual record of this significant, but little remembered, episode in Washington's labor history. Each of the other 11 woodcuts illustrating the calendar was equally powerful and evoked an event or confrontation prompted by the desperation of so many during those traumatic times.

Working for the WPA

As early as 1933 Roosevelt's administration had instituted a relief program for artists, the Public Works of Art Project. Although it only lasted six months, it was an opportunity for artists, including 108 from Washington, to earn regular salaries. They were seen as workers who had families and lives worthy of support, a new concept of artists' role in the community. A subsequent program, the Federal Art Project, was established in 1935 within the extensive Works Progress Administration (WPA) to provide employment for sculptors, graphic artists, muralists, and other artists. The objective was "to conserve the talents and skills of artists who, given the opportunity, are capable of making contributions of the utmost value to the enrichment of American life" (Bullock, 98). Works were commissioned for public buildings and institutions, but artists were generally free to choose their subject matter and were also able to pursue their own creative projects.

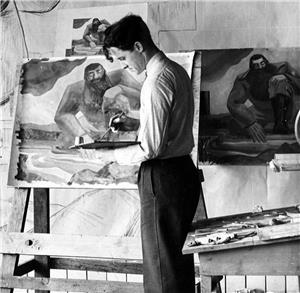

For Correll's life and work, 1937 was a seminal year. At age 33, Correll met Alice Davidson (1916-2009), a Seattle native with a sunny outgoing personality who shared his values and vision. They were married the following year, a union of shared purpose and activities that endured for more than 50 years. And Correll's life as an artist was immeasurably impacted when he was selected for the Seattle Fine Arts Division of the Federal Art Project, joining a "cohort of talented and innovative printmakers" (Bullock, 140) in the Washington program. His salary was an extravagant $96 per month, and he said he'd never worked so hard. Over the next four years he produced a steady flow of woodcuts, linocuts, lithographs, etchings, dioramas for civic projects, and watercolors for the Index of American Design (now in the National Gallery of Art).

In addition, like so many WPA artists, he had his first experience with painting large-scale murals -- decorative scenes in 1940 for Arlington High School in Snohomish County. The Arlington superintendent of schools had a specific request: a mural of Paul Bunyan to memorialize this folk hero of the Pacific Northwest and the importance of the lumber industry to Arlington's past. Correll began with a 9-by-12-foot mural titled Bunyan at Stillaguamish, singularly focused on a frontal portrait of the mythical logger on one knee, dipping his enormous hand into the local river. Another mural featured a farmyard scene with a huge barn dominating the rear; farm workers are busy nearby, and a fenced enclosure with dairy cows completes the foreground. That mural was a nod to the area's local agriculture, and a large picture of Correll working on it was featured prominently in The Seattle Times. Like many WPA mural painters, Correll took inspiration from the work of Mexican artists Diego Rivera (1886-1957), Jose Clemente Orozco (1883-1949), and David Alfaro Sisqueiros (1896-1974), whose complex murals on political themes were then the talk of the art world. In addition to the murals, Correll created illustrations for the high school's yearbook.

The adventures of Paul Bunyan and Babe the Blue Ox had fascinated Correll for years. Like their counterparts in the upper Midwest and Plains states, who told of Bunyan's prodigious size and appetite and Babe's strength that helped scoop out the Grand Canyon and raise the Black Hills, Pacific Northwest loggers had long shared such tales around their campfires and many major Washington landscape features were said to result from the labors of these bigger-than-life characters. Also featured in many of the stories was an engineer -- Billy Puget, or William Peters Puget, or Peter Puget, or Old Man Puget, or just plain Mr. Puget. According to one tale, Puget was hired to dig a huge ditch so that the water from the Pacific could flow inland to Seattle; Paul Bunyan was a subcontractor on the job. One day Puget had a falling out with Bunyan who, with Babe, had been plowing out the channel for the water course and rather casually piling the excavated material into a towering heap (now Mount Rainier) alongside. In the midst of the argument over how the job was being done, Bunyan became so enraged that he seized his gigantic shovel and began throwing dirt back into the channel he had just dug, creating the San Juan Islands.

Among Correll's most enduringly popular works from his years with the WPA is a series of linocuts illustrating aspects of this story. Digging Puget Sound is a powerful scene with Bunyan's huge back dominating the foreground and the churned earth piling up behind Babe, moving with determination toward the horizon. The prints from this series are not large (none more than approximately 16 inches by 12 and many smaller), but line and shading always emphasize not just the size and strength of the subjects but also their energy and effort. DeWitt Cheng (b. 1950), an artist himself as well as a curator, teacher, and art critic, has noted that the print Creation of San Juan Islands "elicits a strong, almost physical involvement from the viewer because the subject is frozen in mid-action, ready to throw the shovelful of dirt forward; his beard even seems to curl back with a life of its own, rhyming with the poised shovel" (Richard V. Correll: Prints and Drawings, 20). Other prints in the series offer different moods -- Paul Bunyan Slumbering or Babe's face charmingly viewed through a Barn Window -- and Correll also produced more works in other media featuring Bunyan and Babe.

One of the benefits of working for the WPA was the opportunity to interact with so many other artists. Often projects were collaborative and artists could learn new techniques, have their works critiqued, and observe how others approached subjects, composition, and interpretation. And always there were the debates about art's role in society and whether it could or should be used to promote social action or whether art for art's sake alone was acceptable. Among prominent members of the Seattle group offering insights and input during these productive years were Morris Graves (1910-2001), Jules Twohy (1902-1986), Z. Vanessa Helder (1904-1968), Fay Chong (1912-1993), Yvonne Twining Humber (1907-2004), Hannes Bok (1914-1964), and Mark Tobey (1890-1976), to whose work Correll was especially drawn. And it was during these years that Correll refined his style. Although experiments in abstraction would excite the imagination of many European and American artists, Correll rejected the impersonal nature of so much of the work while admiring some of the design elements and use of line and space. Seattle's music scene, Correll's encounters with Asian art, and the increasing societal impact of photojournalism all contributed to the growth and maturity of his personal artistic style, but he always returned to themes focused on the human condition and human endeavors. It is notable that his body of WPA artwork was created in more different media than that of any other Washington artist.

Correll maintained a strong interest in political and social causes, creating prints, posters, banners, and other items for political messaging. He was among the founders of the Washington Artists' Union, which he served as secretary. The union was formed to address economic and other issues artists were facing in those hard times. Correll explained, "It is our purpose to make the arts a more direct and more functional service to the life of the community" ("Artists' Union ..."). To increase awareness of the organization and its activities, the group participated in the 1939 May Day parade in Seattle alongside the International Wood Workers of America, American Federation of Teachers, Finnish Women's Club, and numerous other organizations and trade unions. One of the Washington Artists' Union's proposals, based on the relative security artists were experiencing (often for the first time) by having a reliable income from the WPA, was the formation of a permanent art project under the direction of a federal department of the arts. But those efforts were in vain, and by the beginning of World War II it was clear that conservative political forces in Washington, D.C., were gaining ground in the campaign to abolish the Federal Art Project. By 1943 funding had dried up and the project ended.

A Long Career in Art and Political Activism

In a step toward expanding the audience for his art, Correll submitted work for exhibition at the 1939 World's Fair in New York; 800 works were screened by regional committees, and the finalists among the graphic arts were selected by Anne Goldthwaite (1869-1944) and Hugh Gellert, both themselves committed political activists. Correll was honored to have his work chosen. Over the next years, his art was included in exhibitions on both coasts.

By 1941 Correll had decided that New York might offer better employment opportunities, and he and Alice moved across the country. For the next 11 years Correll worked as a commercial artist in the advertising and publishing fields. He also produced his own fine-art prints of landscapes, animals, harbor scenes, and ships; portraits and scenes from the worlds of music and dance; and banners, leaflets, posters, and other materials for the Civilian Defense Corps and political and social causes. In 1945 his work was included in the Artists for Victory exhibition shown at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and in 26 cities across the country and in Canada. He helped establish the Artists League of America, an organization of progressive artists in many fields focused on artists' cultural, economic, and social issues. But Correll found it increasingly hard to reconcile his commercial work with his social conscience and he was uncomfortable in the competitive atmosphere of New York. In 1952 the family, now including daughter Leslie (b. 1944), returned west to the San Francisco Bay area.

Although again doing commercial work to support the family, Correll quickly found a group of like-minded socially and politically committed artists. He helped found the renowned Graphic Arts Workshop and exhibited at the Printmakers' Gallery and elsewhere, while supporting civil, women's, Chicano, and Native American rights causes, as well as antiwar and antinuclear movements. In 1969 Correll retired from commercial work and was at last able to devote full time to his own art and political activities, exhibiting frequently in the subsequent years. He was honored on his 80th birthday in 1984 with a major retrospective and community celebration in Oakland, where he had lived since 1972. Richard Correll died in 1990 at the age of 85.

In 2005 Art Hazelwood (b. 1961), an artist, curator, and historian of political posters, presented an exhibit at the Meridian Gallery in San Francisco featuring two exemplars of the best graphic artists who created works in the service of social causes: Richard Correll and his colleague at the Graphic Arts Workshop, Frank Rowe (1921-1985). In his notes for the exhibition, Hazelwood wrote that Correll's "linocuts and woodcuts ... reflect his sympathy with organized labor, his dismay at the devastations of poverty, racism, industrialization and war with a power and determination surprising in such a gentle soul" ("As They Saw It"). That same year Correll's daughter Leslie and others completed a book that Correll himself had started and for which he had gathered some of his best work. Richard V. Correll: Prints and Drawings offers a glimpse of the range and strength of both his fine art and his political cartoons and posters. And 2005 was also the year that the wide-ranging Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project, a collaborative endeavor based at the University of Washington, was launched.

Labor Archives of Washington

Leslie Correll wanted her father's legacy to reside not in an art-focused institution but in an established collection devoted to labor, unions, and working men and women, the subjects that had been so important to him throughout his life. Discussions with the Civil Rights and Labor History Project staff introduced her to the Labor Archives of Washington, established in 2010 as part of the Special Collections of the University of Washington Libraries. In 2012, she donated Correll's lifetime of work to its care. The Labor Archives, with more than 300 collections of materials from individuals and organizations related to labor and unions, contained at that time primarily documents, newspapers, and other textual materials. Correll's graphic arts and other visuals were an important and complementary addition. The donation included woodcuts (and some original printing blocks), lithographs, serigraphs, linocut prints, drypoint etchings, photostats, drawings, paintings, an oral history on tape, and scanned photos of his work. Much of the collection has since been digitized, offering easier public access.

The Labor Archives celebrated the acquisition of the Correll materials with a special exhibition in the University of Washington Libraries that opened on December 6, 2012. Head archivist Conor Casey provided numerous media presentations, articles, and internet postings describing the collection and Correll's contributions to the labor and civil rights movements. After the exhibition closed the following April, a traveling exhibit was created to bring Correll's work to a broader audience; its first showing was at the 2013 Northwest Folklife Festival, a popular annual Seattle event.

From the 1930s through the 1980s, Richard Correll created a large body of fine art and, at the same time, generously contributed his talents to rallying supporters, conveying core messages, and recording the people and activities that were at the heart of so many important political and social movements of the times. Having Correll's work accessible at the Labor Archives of Washington is an enormous benefit for future scholars and others interested in his extensive and varied output, with his images remaining as impactful as they were at the time of their creation.