Few changes to the Seattle landscape were as epic as the regrading of Denny Hill, which took place between 1897 and 1930 and involved five separate projects. Located between downtown and Queen Anne Hill, Denny Hill originally topped out at about 220 feet in elevation, about half the height of hills such as Queen Anne, Capitol, and Magnolia. The drivers for the regrades were business and the hope that removing the hill would create a tabula rasa open to new and better ones. By the time regrading ended, the hill's high point had been lowered by more than 100 feet to create the mostly flat land now known as the Denny Regrade.

The Engineer

Like many new residents of Seattle in the early 1880s, Reginald Heber Thomson (1856-1949) came to the city because of its great potential. With abundant coal and timber, and the impending expansion of train service into the city, Seattle was a perfect opportunity for a young man, particularly a budding engineer such as Thomson. He hoped to change his luck in Seattle. Born and raised in Hanover, Indiana, Thomson had taken surveying classes in college but otherwise had little professional experience when he landed in the city. He did though have a cousin, Frederick "Harry" Whitworth (1846-1933), who was Seattle's city surveyor. Whitworth also had a private practice and hired Thomson to join him. Working for his cousin, Thomson got to know the land in and around Seattle surveying for the railroads, property owners, and the local coal mines. In August 1884, one year after his cousin Harry quit the job, Thomson became the city surveyor, a position equivalent to the city engineer.

Thomson's "greatest triumph" during his early years, wrote his biographer, William Wilson, was building the Grant Street Bridge. This wooden trestle ran out over the tide flats along the base of Beacon Hill and would become a major transportation route south of the city. The structure exemplifies a central theme of Thomson's: connecting disparate parts of the city. As he later wrote in his autobiography, with such a hilly landscape, he wondered, "how will the people in one end of the city be able to do business with those in the other end?" (That Man Thomson). The answer was to regrade what was in the way and open corridors for people to get where they needed to easily and quickly.

Seattle, noted Thomson, was particularly in need of this kind of fix. The problem was that the city's founders had platted the land "with but little regard as to whether the streets could ever be used or not, the main idea being, apparently, to sell the lots" (Annual Report, 1908). What they should have done, instead, was to lay out the trails and roads first. Not that Seattle was alone in making this error. "In the ruins of very ancient cities, we find evidence that the same character of work— that is to say the work of regrading — was carried on before the beginning of history," wrote Thomson (Letter 1909). Now it was Seattle's time to carry out this ancient process, and he knew the perfect place to puts his ideas to work -- the offensive Denny Hill.

Location

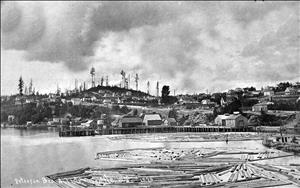

As with most neighborhoods, no one had, or has, a precise definition for the location of Denny Hill. The hill was originally known to settlers as Capitol Hill because Arthur Denny (1822-1899) had set aside 10 acres in 1860 at the southwest corner of the hill for the state capitol. Although fellow pioneer Daniel Bagley (1818-1905) convinced Denny that the state university would be better to have than state government, the name Capitol Hill clung to the high knoll. It didn't obtain the name Denny until 1889, when Denny and other developers started work on the grand Denny Hotel on Denny's proposed location for the capitol.

Denny Hill's physical boundaries depend on whether you look at it bureaucratically or topographically. From a regulatory standpoint, Denny, or at least its regrades, conformed to street boundaries, roughly between 1st Avenue, Westlake Avenue, Pike Street, and Broad Street. In total, Denny encompassed about 65 city blocks, or a little over 200 acres. In 1893, there were at least 320 single-family and 69 multi-family homes, along with 26 stables, 218 sheds, and 10 hotels within this area (Raymond thesis).

Early topographic maps show the hill extending north to Thomas Street (across the street from the modern location of the EMP Museum). From this low point, Denny ran due south and gained 120 feet to its northern summit at 4th and Blanchard. A second high point, the one that would be the location of the Denny Hotel, rose between 2nd and 3rd on Stewart Street. Rising nearly 100 feet from Pike Street to the base of the hotel construction, the hill's south side was a formidable obstacle, but it was hardly impassable.

Early Regrades

In his biography, Thomson wrote that, "Seattle was in a pit, that to get anywhere we would be compelled to climb out if we could." He resolved to "persevere to the end" (That Man Thomson). For Thomson and others, Denny Hill was the greatest impediment to going anywhere. Local newspaperman Welford Beaton (1874-1951) summed up the historic viewpoint on the topography in his history of Seattle, The City that Made Itself: "The hills raised themselves in the paths that commerce wished to take. And then man stepped in, completed the work which Nature left undone, smoothed the burrows and allowed commerce to pour unhampered in its natural channels."

After living in Seattle for more than 15 years, Thomson, who had become the official city engineer in 1892, finally had a chance to begin the removal of Denny Hill. In late 1897, less than six months after the beginning of the Klondike Gold Rush, the city council passed, with Thomson's guidance, an ordinance authorizing the regrading of 1st Avenue between Pike and Denny. Although it was the smallest of all regrade work done on Denny Hill, the project set the stage for the many regrades to follow. Contractors used water from hydraulic hoses to wash away the hill with most of the 110,700 cubic yards of sediment ending up unused for anyone's benefit in Elliott Bay. The regrade, noted The Seattle Times, was "endurable only for the sake of the promise of ultimate improvement," though it did lead to increased property values ("Grading A Thoroughfare").

With 1st Avenue washed into the bay, Thomson turned his focus to 2nd Avenue. An ordinance for the regrade passed the city council on March 2, 1903, and the contractor started working in August. Because of the geography and location of buildings, workers supplemented the hydraulic hoses with steam shovels to remove more than 600,000 cubic yards of material. Most of this sediment ended up deep in Elliott Bay, carried out by a trestle built at Battery Street.

The third bite into the hill began in May 1906. Contractor H. W. Hawley won the contract and, working with steam shovels and hydraulic hoses, cut away 650,000 cubic yards of the south-end hill. Unlike other regrades, more than half the dirt that Hawley removed went some place besides Elliott Bay. A small steam railway colloquially known as the "Mount Moses, Denny Hill, Central & Westlake Valley Airline" ferried the dirt across a trestle and dumped it in the area around Pine and Olive Streets, creating the smoothed out, relatively gentle slope that now ascends past the Paramount Theater to Capitol Hill ("Work Begins ...").

The Geology Facilitates Regrades

Part of what made Seattle's regrades possible was the underlying geology. During the most recent ice age, which ended around 16,500 years ago, an ice sheet spread south from Canada between the Olympic and Cascade Mountains and reached to just past modern-day Olympia. At the glacier's greatest extent it was about 3,000 feet thick in Seattle. As it moved through the region, the ice led to the deposition of three layers of sediment, such that if you could cut open any hill in Seattle, you'd find a three-layer cake of clay, topped by sand, capped by a mix of sand, cobbles, and boulders. In essence, Denny Hill is basically a big pile of dirt, smushed and consolidated by the great glacier.

Because the hill is not solid bedrock, such as the basalt under Portland or gneiss under New York City, all that engineers needed to remove Denny was water. The tool they employed was a hydraulic cannon, or "giant," as they were called. It was technology that had been used extensively in the Klondike Gold Rush. A typical giant was operated by a five-man team. One man fired each giant, holding a 3-foot-long handle connected to a cast-iron nozzle. The 7- to 10-foot-long nozzle sat on an articulated base and had an adjustable opening from 3 to 5 inches in diameter. Each giant team also included someone to direct the muddy slurry in the pit to a pipe that carried the former hill away. The boardman also removed roots or similar material that could choke the system. Another man monitored the iron bars, or grizzly, at the mouth of the pipe, which kept out larger rocks and lumps of clay. He, too, removed or sledgehammered the larger material into smaller bits. Under normal conditions, a crew could wash away about 1,000 cubic yards of material each eight-hour shift, or enough sand and gravel to fill 6,750 wheelbarrows.

The water for the regrades came from a variety of sources. For the Jackson Hill regrade between 1907 and 1909, in what is now the Chinatown International District, the contractor sucked water from Elliott Bay and Lake Washington, as well as using city water, which came from the Cedar River. Another hydraulic project on Beacon Hill in 1904 and 1905 used city water. For the fourth regrade of Denny Hill, contractor Grant Smith & Co. & Stilwell extracted water out of Elliott Bay using pumps built by H. W. Hawley for its work on the south end of Denny Hill during the previous regrade. The Hawley machines provided 5 million gallons a day. Supplementing their saltwater source, GS&C&S installed three pumps on Lake Union, and fed 18 million gallons a day through a mile-long pipe up 8th Avenue to two distribution points on Battery Street, at 3rd and 5th avenues.

(One of the general items of common misinformation about the regrades is the use of city water. On Denny Hill none was used, with only about one quarter of the Jackson Hill water coming from the Cedar River.)

To get rid of Denny Hill, it was decided to dump the hill into the deeper water of Elliott Bay. The muck would travel during the fourth regrade via an 875-foot-long tunnel excavated from Bell Street and 2nd Avenue to Elliott Avenue. (It's not clear why the fill was wasted. The P-I of April 8, 1909, noted that negotiations on selling the earth for fill "came to naught" but does not say who was involved in these discussions.) The same issue would arise in the final regrade of Denny. The timber-lined tunnel, tall enough for a person to stand up in, led to a flume, or sluice, that passed over the tracks and roadway of Railroad Avenue and discharged the hill into the water.

By the time the contractors finished the regrade, the flume extended on pilings for 1,200 feet into Elliott Bay. It was quite an engineering marvel as they had to use 125-foot-long piles, which they drove into previously dumped fill, in water that had been 200 feet deep. To spread the fill widely, the flume had three distribution points, which allowed the pile driver to extend one arm of the flume into deeper water while the other two continued to dump Denny. Because of all the sediments, the turbidity was so bad near the dumping site that fishers complained it had driven away cod from the docks and out to clearer water. Throughout most of this round of the regrade, water provided enough force to dislodge the hill, but workers also used dynamite to supplement the giants when they came across boulders, or hit hard lenses, or layers, of sediment.

Bureaucracy

Far larger than the previous three, the fourth regrade would chop off the entire west side from 5th Avenue to 3rd Avenue between Pike and Denny. As with all the previous regrades, the fourth began with R. H. Thomson seeking signatures for a petition to remove the hill. A project such as a regrade required at least 50 percent of those who lived in the area that would be altered to sign a petition calling for the land change. Thomson's team turned the petition in on April 28, 1906. Mayor William Hickman Moore (1861-1946) signed Ordinance 13776 on May 23, 1906. It established what property the regrade would remove. A second ordinance, number 14993, provided the funding mechanism, or what was known as a Local Improvement District.

First used in Seattle in 1893, the LID made the landowners pay for the improvement of their own property, as opposed to forcing the city as a whole to pay. How much a property owner owed was based on a simple formula. On the plus side was the appraised value before the regrade; the owner would be paid for any buildings destroyed during the project. The owner would also add to the plus column any theoretical damages to the property caused by lowering the street. On the negative side were the costs of rebuilding the infrastructure, which was divided among all who benefited, in proportion to how much their property would benefit. To determine these values, a judge appointed a commission, in this case three "young and ambitious" men, two lawyers and an engineer ("Denny Hill Tax ..."). They held a series of public meetings, visited the properties, and sent out inquiry letters, after which they presented their findings. If the owners didn't agree with the commission, they could appeal through the courts.

Many perceived the process as unfair, though a better term might be arbitrary. The commission made mistakes and probably was influenced by politics, but many of those poor decisions were corrected by appeal and just a handful of cases made it all the way to the State Supreme Court. As Thomson's biographer, William Wilson, who has written the most detailed account of the Denny Hill LID and appeals said, "the problems didn't so much lay with the process as it did with what happened afterwards" (author conversation). Homeowners had 10 years to pay back their assessments at a rather steep 6 percent interest. In addition, they had to pay taxes on the new, generally higher assessed value of the land. They also had to pay the contractor separately for lowering their property. Many could not afford to make these payments.

With most of the court cases settled, the city called for bids to be opened in July 1907. Rainier Development Corporation won the contract with a bid of $0.27 per cubic yard to regrade the city streets. In signing their contract, Rainier also agreed to excavate all private property at the same price as the city paid, but only if landowners agreed to have their property excavated at the same time as the city. One year later, Thomson sent a letter to Rainier to "begin work forthwith." They would have 30 months to complete the removal of 5.4 million cubic yards of Denny Hill. This long-desired regrade began when subcontractor Grant Smith & Co. & Stilwell started washing away 3rd and Bell in August 1908.

Work began slowly with just 8,000 cubic yards of material excavated in August 1908. It didn't help that technical difficulties meant that the contractor only got four days of work done that month. The total jumped to 42,000 cubic yds in September and 130,000 cubic yards in November with a peak of 294,500 cubic yards in October 1909. By November 1910, more than 97 percent of the hill had been removed.

Spite Mounds

Part of what remained has become one of the most famous aspects of Denny Hill and of Seattle history: the isolated buttes known as spite mounds, spite heaps, or spite humps. In May 1910, six of these notorious pillars of private property rose above the flattened surface of the hill. Five property owners had left the mounds high, supposedly protesting the city's plans to level the hill.

As far as the records show, however, none of the owners were against cutting down Denny Hill. One of the mound holdouts, Zachariah Holden (1850-1912), had owned his house at 5th and Virginia since 1883, when it was "far beyond the hum of the traffic of the little town" ("Massive Buttes ..."). He told a P-I reporter that he hadn't initially signed up to have his property lowered because he didn't have the money needed to pay for the work. Holden eventually was able to borrow the necessary funding to pay to eliminate his spite mound. "I want to see every vestige of these hills come down," he said. "[I] would have been willing to make greater sacrifices to see Seattle become greater still" ("Massive Buttes ...").

James T. Kelley (1861-1940) owned two of the mounds, one at 4th and Virginia and one at 4th and Bell. Each rose about 100 feet. A former owner of a small meat market, Kelley had gone north in search of Klondike gold and made a fortune. He was in the north working his mines when the contractor had sought authorization to cut down his property. When he arrived back in Seattle in summer 1910, Kelley, too, said that he supported the removal of Denny Hill. "I have lived too long in Seattle ... to be accused of being actuated by spite on any matter connected with public improvements ... After full consideration of the matter and in the belief that the Denny Hill regrade district should be rapidly improved, I have decided to improve my holdings" ("Two Of Tallest ..."). By January 1911, both mounds were gone.

Kelley and Holden, like most of their neighbors, heartily supported the Denny regrade. They appeared to do so for two reasons. Many must have agreed with Thomson and Beaton that the regrades would benefit the entire city, and that an improved Seattle with easier transportation routes, more space for industry, and room for businesses to spread would be a better place to live. Others also believed that they would make money by being able to sell their lowered property.

Nor is there evidence for another common urban belief, that homes were left on the mounds, forcing the owners to reach their residences by ladders, steep stairs, or mountaineering equipment. There are photographs showing isolated homes on what appear to be buttes, but no one wrote about or photographed anyone commuting vertically to them. Plus, any homeowner who wanted to lower their house to the new post-regrade elevation had to wait until the surrounding land was gone.

The Department of Public Works declared the regrade to be done on June 20, 1911. And then the regrade of Denny came to a halt. Politics, other city projects such as the completion of the Lake Washington ship canal and locks, and lack of commerce pouring "unhampered in its natural channels" (few businesses had moved into the area lowered during the fourth regrade) led to 17 years passing before the beginning of the fifth and final regrade.

Fifth Regrade and Some Big Shovels

In contrast to previous projects, the contractor did not use hydraulic giants in the final regrade. Too much of the area surrounding the regrade had been developed, so funneling a muddy stream across paved streets heavy with traffic was not practical. Previous regrades had also shown that the giants always needed assistance from dynamite and power shovels, or excavators. The excavated sediment, though, continued to end up in Elliott Bay, carried to the water's edge by an extensive conveyor-belt system, and transported out into the water by one of the engineering marvels of the Denny regrades: self-dumping wooden scows.

Designed by naval architect William C. Nickum (1874-1951), they were mirror image top and bottom with open decks that held 400 cubic yards of dirt. Between the decks were two internal tanks, one on each side of the scow. A tug towed the full scow out into Elliott Bay, where a crewmember pulled a rope that opened valves, or seacocks, on one side of the boat. Within three minutes, water filled one of the tanks, and the out-of-balance scow flipped over, dumping its load. No longer weighted down by the dirt, the scow rose high enough to drain the internal tank, which took about eight minutes. The tug then pulled the scow back to shore, ready for its next load.

Preliminary work on cutting down the last of Denny Hill began in February 1929, with a power shovel removing dirt along 5th Avenue for construction of the main conveyor belt. By May, the contractor was ready to go at Denny with the two big electric shovels munching into the hill on Battery Street at 5th and 7th. With all five shovels in operation, each day would see the hill reduced by more than 12,000 cubic yards.

By December, the hill was almost gone. The crews had been unrelenting. After a slow start in late 1929, the contractor had worked out its problems and was completing a task that many thought impossible just months earlier. Bite after bite of the hill fed into the hoppers, dropped onto the ever-moving conveyor belts, and shot along at 600 feet per minute to the waiting scows and the dirt's final voyage out into Elliott Bay.

On December 9, 1930, shovel operators spent the day racing each other to "clear 'er up" for a final celebration. "That once great promontory, thrown up by nature ages ago to make trouble for Seattle's progressive expansion," was now merely one shovelful of earth, noted the Times ("Denny Hill Gone"). "At last the way was opened for giant new buildings, for the forward sweep of the central business district northward on level grades into territory which only a few months ago barred progress with a lofty barricade of clay banks, ill-kept streets, run-down residences, aged public and semipublic structures" ("Mayor Finishes Regrade").

A 11 a.m. the next day, Seattle Mayor Frank Edwards (1874-1943) climbed into one of the electric shovels between Battery and Wall Streets, near 6th Avenue, pulled a lever, and the final cubic yards of the hill vanished. Hundreds stood by, including many who had been born on the hill, who had attended Denny School, and who had lived there. "There were many moist eyes," wrote a reporter for the P-I ("Good-By Denny ..."). With Edwards's final dumping of the dirt, 4,354,625 cubic yards of the hill had been removed. Total cost was $2,261,800. Total sediment moved during the five regrades was 11,112,025 cubic yards.