Reef-net fishing technology is unique to the Salish Sea, where it was devised at least 1,800 years ago as a way to intercept vast midsummer runs of sockeye salmon as they passed through the San Juans and southern Gulf Islands on their way to the Fraser River. Reef nets were closely associated with the Northern Straits Salish language, spoken by ancestors of present-day Saanich, Samish, Songhees, Sooke, and Lummi communities of lower Vancouver Island and mainland Western Washington, although reef-net crews also often included in-laws from Halkomelem and Lushootseed speaking villages to the north and south of the Straits Salish linguistic area. Reef-net "gears" are easily recognized as pairs of canoes or floats, between which were suspended nets and funnel-like leads facing into the current. Part 1 of this two-part history describes how and where reef nets work, and details the complex technology and social organization that allowed Coast Salish reef-net sites to produce salmon on an industrial scale.

An Island Technology

Reef-netting was only one of the technologies devised by Coast Salish peoples for harvesting summer salmon runs on a sufficiently large scale to provide dependable winter food supplies for the harvesters, as well as a substantial surplus for trade with other Salish Sea villages and east of the Cascades. A considerable salmon surplus was also essential for raising flocks of dogs specially bred for their hair, which was spun into yarn used in clothing and other textiles. Barrier weirs in rivers, tidal weirs in estuaries, and various kinds of fish pounds and trawl nets were widespread on what is now mainland Western Washington and southwest British Columbia.

In contrast, reef nets were specific to the San Juan Archipelago, from Lummi Island west to Pender Island, through which most of the salmon returning to the Fraser River in British Columbia must pass. As Saanich elder Dave Elliott Sr. explained, Coast Salish villages located on big rivers "don't have to go anywhere for fish" since "the salmon comes home to them every year" (Salt Water People ..., 52). But villages in the islands had to find a way to intercept salmon in open seas, which only worked at a small number of coastal stations.

Reef-net Gear

The heart of a traditional reef-net "gear" was a bag-like net, roughly 40 by 40 feet (more or less), woven of twisted willow-bark twine and secured by heavy ropes made of steamed and twisted cedar withes. Nets were dyed dark colors so that they would be less visible to target fish. A small piece of a reef-net from Stuart Island, retired when the owners switched to commercial cordage in the 1920s, is preserved at the Orcas Island Historical Museum. Dave Elliott explained that the word for reef net, sxwáləʔ, "comes from the word for willow tree," which is sxwǝli?iłč in Straits Salish (Salt Water People ..., 52). The suffix -iłč refers to a shrub or tree, so it would also be reasonable to translate the Straits Salish name for willow as "reef-net tree." Willow-twine nets remained in widespread use until canneries were built in the 1880s, giving reef-net captains cash they could use to purchase commercial twine and netting.

The net must be anchored in place each fishing season, and for this purpose large rocks pried from outcrops along the shore, weighing an estimated 200-400 pounds each, were trundled onto cedar planks athwart the broad mid-section of canoes and dropped in place one-by-one at the direction of the owner of the site. Twisted-cedar anchor lines could reach more than a hundred feet long. Once a big anchor stone had been set, smaller rocks were dropped down, looped to the main anchor line, forming a heavy rock pile that could withstand the forces of tides and current. Ethnographer and linguist Wayne Suttles (1918-2005) was told that it took two to four men to lift each stone onto the canoes. Long before mechanical winches or hydraulics, it was impractical to retrieve anchor stones once set. Anchor lines could be secured to inflated sealskin floats for re-attachment the following spring, but most anchors had to be replaced every year. Each gear required a minimum of four anchor lines: one line on the bow and stern of each float.

Over decades of use, reef-net sites accumulated large piles of anchor stones, identifiable by their roughly uniform size, composed of exotic material in comparison to the substrates on which they rest. Scuba surveys in the 1980s and ROV (remotely operated vehicle) dives in 2003 were able to locate anchor-stone piles at a number of sites identified from ethnographic literature. A significant characteristic of the sites documented on ROV video was the abundance of rockfish nesting among the anchor stones. It appears that reef-netting created rockfish habitat; or, in different terms, reef-netting created artificial rocky reefs. Old-timers took advantage of this phenomenon by dropping a baited hook and catching lingcod and rockfish "for lunch" while working the reef nets (Daniels interview).

Reef-net Antiquity

When fishery biologist Richard Rathbun (1852-1918) interviewed Northern Straits Salish reef-netters Joseph Cagey and Dick Edwards about their Lopez Island fishery in 1895, they told him that Coast Salish "have been fishing there ever since there was Indians on the island. You can see the clam shells there 10 feet deep where they have been living there" (Cagey and Edwards interview). Indeed, an important state-registered archaeological site is exposed in a cut-bank viewable from Iceberg Point at the south end of Lopez Island where the Cagey-Edwards reef nets were located. Its deposits extend back several thousand years based on criteria proposed by archeologist Julie K. Stein, who visited the site in 2004.

Cagey and Edwards also fished a backup site at Watmough Bay on Lopez Island, four miles from Iceberg Point, where there was a smaller shore station for processing reef-net salmon atop some 3,000 years of cultural deposits. A 2004 archaeological excavation recovered salmonid remains from multiple levels of that site. Genetic analysis of the remains detected a change from a mixture of salmon species to mainly sockeye salmon roughly 1,800 years ago, which is consistent with a switch from angling and spearing salmon to the use of more selective reef nets.

A number of interrelated Northern Straits Salish stories are associated with the reef-net fishery. Their common trope is the marriage of a young woman with a handsome, talented stranger who comes from the sea, or is first encountered on the beach, and brings the gift of vast wealth of salmon. In a Saanich version, the handsome stranger teaches the family of his bride how to strip willow bark, twist it into twine, and weave nets. The Samish version is associated with Kwəkwáləwət, the "Maiden of Deception Pass," memorialized by a massive carved-cedar welcome figure at Rosario Beach in Deception Pass State Park. In all versions, the young couple eventually departs to live together deep in the sea, returning from year to year to visit their human kinfolk. This underscores the relationship between humans and salmon: one in which humans must behave respectfully in order to continue to enjoy the bounty gifted them by the ocean.

Why Reef Nets Work

Adult sockeye and pink salmon return to the Fraser River between midsummer and early fall, where historically they arrived in vast aggregations of tens of millions of fish. Their migration path takes them around southeast Vancouver Island, around and through the San Juan Islands, and past Lummi Island and Point Roberts. As they migrate through these shallow marine waters, they conserve energy for their upstream struggle by resting and feeding in shallow bays where they find herring, shrimp, krill, and squid. Energy conservation during migration is a factor in the size of eggs and larval growth rates.

After resting and feeding in a small bay or eddy, salmon depart with the tide, catching and "riding the current," traveling fast while veering away from kelp forests and rocks (Vandersluys interview). One or more reef nets were set across their path, with 100-foot-long floating lines forming funnels leading into the nets. Bunches of beach grasses were woven into the lines so that underwater they would float and wave, mimicking the behavior of eelgrass in shallow water. The lines forming the funnel were disguised to look like the entrance to a tidal inlet, where the salmon would be relatively safe from large predators such as orcas. The number and alignment of the lead lines were adjusted to individual fishing sites.

"These fish are going fast because they're going with the tide, the fish behind them can't see [the net], and they're pushing the ones ahead, so before they know it they're in the lead. They fooled the fish, that's what they did ... As the fish come, they can't turn around because the tide is pushing them. Besides the fish behind them are pushing them and they just keep going. All of a sudden they come to the end of the lead [line] and the water is clear green. It looks like all this danger is passed and you can actually see them speed up when they see this. Then they go into the net" (Salt Water People ..., 52).

At some reef-net sites, the funnel reportedly could be a channel cut into a kelp forest. However, nearly all of the reef-net sites identified by Wayne Suttles are 80 to 120 feet deep, and kelp forests do not ordinarily grow on substrates deeper than about 65 feet. Interestingly, at these depths salmon could simply swim beneath the gears to avoid being trapped -- "floor lines" for the leads were only about 14 to 18 feet below the surface. The trick is the deceptive refuge offered by the net with its grassy disguise, which (as more than one old-timer described it in conversations with the author) brings salmon "up from the deep" close to the surface.

The role of the front watchman is to alert the crew when salmon enter the leads so that they will be ready to pull the two floats together, raising and closing the net. Orcas and other predators often followed salmon into the net as well. Cleve Vandersluys said a "finback" whale (orca) went through his gear once in Open Bay (Vandersluys interview).

Some sources assert that reef nets can only be operated in calm weather with clear, calm seas, so that salmon can be seen entering the net. However, summer algal blooms can reduce visibility of fish to a few inches. Reef-netters often used the movements of predators (seabirds, seals), the changing sounds of surface water, and other cues to detect the proximity of approaching schools of salmon, and salmon in the net create a disturbance that can be felt on the float and towers. Ralph Lillie recalled learning to listen for fish when the water was too dark and soupy to see them run into the leads. It was not without reason that nineteenth-century cannery owner John Elwood claimed that only the "older men" among the reef-netters could tell when the salmon were running (Elwood interview, 12). It took more than patience and keen eyesight.

Coast Salish fishers believed that salmon schools have leaders. Traditionally described in English as "kings" or "queens," salmon leaders were said to have "crooked noses" -- that is, hooked mandibles or "kypes." Biologically, the development of kypes is mediated by changes in hormone ratios as salmon mature sexually. Salmon mature at different rates as they migrate through the gradually diminishing salinity of the Salish Sea, and some of them develop mature sexual characteristics before actually entering their natal rivers and streams.

Traditional Straits reef nets had an open ring of willow withes about a foot wide at one end. Elders have said that this made it possible for some salmon to escape and spawn. Others held that salmon did not escape, and if the leader tried, it would die. Betty Loman, known as "Reef Net Betty," reported that many fish escaped over the sides as the net was being hauled up, which she argued made the reef nets of her era -- the 1930s -- unlike fish traps and exempt from the 1933 state law banning the use of fixed gears. Regardless, it is likely that reef nets intercepted only a fraction of the salmon runs that migrated past them.

The principal target of reef nets was Fraser River sockeye salmon; it was a sockeye that was celebrated in the first-salmon ceremony. Other salmon were often caught as well, however, and in the mid twentieth century, reef-netters experimented with positioning gears in shallower water to target coho salmon and "spring" salmon (early Chinook) as well as pinks.

Where Reef Nets Work

Proximity to a major sockeye migration path is not sufficient. To be productive, a reef net must be situated precisely where a natural bottleneck constrains the movement of large numbers of migrating salmon -- just outside a small bay, where strong currents, steep drop offs, and kelp forests force salmon to stream close to shore. Salmon ride the tides as a way of saving metabolic energy: "The tides lead the salmon" (Thomason interview, 2).

In Straits Salish, a place where reef-nets work is called sxwálət. "[T]he tide has to be just right before they will work" (Salt Water People ..., 53). The sxwálət tend to be south facing, which in the islands means that the ebb tide would run southward into the net. The author has observed this at Stuart Island, where the flood tide visibly pushes salmon into the bay and the ebb tide pulls them out again to where the Chevalier reef net is waiting. Other sites worked the flood tide, however, and some -- like the Four-Way gear at Fisherman Bay on Lopez Island operated by Jack Giard -- can fish both tides. Anchor lines at the rear end of the net can be adjusted to aim the lead lines directly into the tidal flow.

The term "reef net" is misleading in contemporary English, since "reef" means a "chain of rocks or coral or a ridge of sand at or near the surface of water," and has held that meaning for centuries (Merriam-Webster). The earliest published reference to Salish Sea reef nets appears to be Richard Rathbun's 1899 report for the U.S. Commissioner on Fish and Fisheries, which notes that "off the south end of Lopez Island, directly east of San Juan Channel entrance ... for many years the Indians have made successful catches on the kelp-covered reefs" ("A Review ...," 266). This refers specifically to the gears operated by Northern Straits fishermen Cagey and Edwards interviewed by Rathbun. Suttles repeated Rathbun's reference to gears being anchored "on a kelp covered reef" (The Economic Life ..., 155).

The author explored this site in 2003, including locating the old anchor stones. The gear was anchored in a sand flat about 100 feet deep -- hardly a "reef." The edge of a kelp forest, growing on rocks in 20 to 30 feet of water, is plainly visible between the anchor site and the high sandy bluffs that line the shore. More than one reef-netter told the author that salmon "bounce off" kelp, which makes ecological sense since seals and other large predators can hide beneath the kelp canopy. A gear is often situated close to a kelp forest, then; but this has nothing to do with a "reef." The present-day Chevalier gear on Stuart Island also has kelp between the gear and the shore, whereas the highly successful Four-Way gear at Fisherman Bay, Lopez Island, is anchored at the edge of a broad, dense eelgrass meadow close to a gravelly beach.

Betty Loman described the lead lines, decorated with grasses, as "imitation reefs" (Loman, 2). This may be a better explanation of the English term "reef net," although eelgrass does not ordinarily grow on "reefs," shoals, or sand spits, but rather in shallow bays or lagoons. A lagoon entrance is what the decorated leads suggest. It is possible that early observers confounded the design of reef-net leads with the widespread practice of cutting canoe paths through the canopy of kelp forests. Canoe channels would certainly have been common around reef-net sites to facilitate the transportation of crew and fish to shore camps.

In any case, it was crucial to replace the gear each summer at precisely the same location. "Gears were anchored by lining up with trees and houses on shore" (Vandersluys interview). The first anchor "was put down exactly where they wanted it because they had bearing marks from the shore. They lined up the bearing marks and when they were in line, down went that anchor" (Salt Water People ..., 54). Knowledge of these shore points was passed down from one owner-custodian to the next for generations.

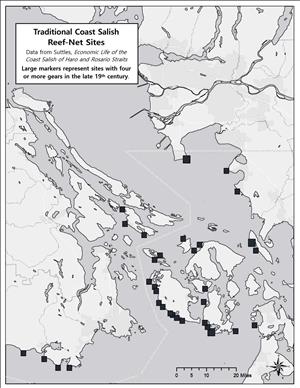

Wayne Suttles was able to identify the names, locations, and most recent Coast Salish owners of 34 traditional reef-net sites in the San Juan Islands, many of which supported multiple gears. Most were located on the southwest side of San Juan Island and the south end of Lopez Island, marking the main migration routes of sockeye salmon returning to the Fraser River. There were also large concentrations of reef nets at Lummi Island and Point Roberts, close to the Fraser River Delta.

The Point Roberts reef-net fishery is a special case, a sandy shoal near the mouth of the Fraser River that provided a natural platform for as many as 17 shore-anchored nets lined up in a tight arc side by side running out from the shore. The gears supported a substantial summer village of numerous cedar-plank houses with room for several hundred people. According to John Elwood, who Rathbun interviewed in 1895, Straits Salish fishers claimed that the Point Roberts and Lummi Island gears were anchored near kelp forests because "there is a small crustacean around those kelps" that sockeye salmon particularly savor (Elwood interview, 11-12). But Elwood noted that the most productive gears were anchored in deep water close to rocks, which sounds more like the sites that the author has surveyed in the islands.

Organization, Ownership, Preparation, and Ritual

Reef-net fishing produced salmon on an industrial scale. Landing thousands of fish each day required a large number of people to operate boats and nets, and even more ashore to clean, dry, and bundle the fish. The summer reef-net camp could be hundreds of people. Each gear had a crew of six to 12, and their families helped process the catch on shore. Organization at each sxwálət (reef-net site) was entrusted to an owner or custodian, or a pair of "business partners" that were responsible for choosing captains for each of the gears, allocating campsites, and supervising the distribution of shares of the catch. Although it has been customary to refer to custodianship as "inherited," Suttles's genealogies of more than 30 reef-net sites demonstrate that in reality succession was more complex and pragmatic.

In Coast Salish thinking, the custodian represented the families that routinely returned to fish together each summer. The custodian was a worthy person given the traditional name associated with that sxwálət. A feast was appropriate to publicly ratify the transfer of the traditional name to a new custodian, together with the canoes and gear. As Suttles observed, fishers often simply took over a site from a relative or in-law, but if there was a dispute an elder who "knew the stories" would be asked to help untangle conflicting claims (The Economic Life ..., 216). Reef-net custodians were typically siém (literally "people of substance") who exercised influence over their families and villages, energized by their ability to grant fishing privileges and distribute fish. The custodian often built a small personal cedar-plank house at the site for seasonal use, another symbol of influence and wealth.

Significantly, the custodian generally had exclusive knowledge of the exact location of the anchors and optimal alignment of the gear and its leads, which were learned from the previous custodian. This remained true even in the 1940s and 1950s, after most gears had been acquired by non-Indian islanders. Cleve Vandersluys, who set anchors for mid-century reef-net gears with his boat Hydah, recalled: "Most reef-nets were owned by one person. He didn't tell anybody anything. No one else knew how to use it. Fishermen had to practice awhile until they got it [a gear] fishing right [in terms of] depth and slack" (Vandersluys interview).

A considerable amount of effort and expertise was required for preparation every year, beginning with the production of twine and weaving of the net in pieces by the families of crew members and assembling the pieces, followed by replacing some of the heavy cedar lines that anchored the gear in place; establishing the summer salmon-processing camp composed traditionally of cat-tail-mat lean-tos and fish-drying racks; and dropping new anchor stones where needed. In addition to knowing how to line up the anchors precisely, the custodian was expected to give the signal to start fishing. Lena Daniels, granddaughter of the last custodian of the west Orcas reef nets more than a century ago, remembered her grandfather watching the water for signs of arriving salmon, and waiting for the "first run" to pass fully before alerting his captains that it was time to fish (Daniels interview).

Each stage of the preparation process was accompanied by rituals, from calling the salmon, celebrating the setting of the anchors, and welcoming the first salmon caught, through celebrating the end of the fishing season before packing up camp. Custodians addressed the salmon in kinship terms, with sockeye occupying the highest social rank. A salmon-calling song recorded by Harry Smith in 1942, sung by Lummi reef-net custodian Julius Charles, addresses the fish as kinsmen and urges them to be careful as they approach the net. Suttles heard a Semiahmoo song at Point Roberts that traced the progress of the returning sockeye salmon from Becher Bay on Vancouver Island through the San Juan Islands, and urged them onward, as a high-status leader might extend an invitation to a feast. This recalls the Northern Straits tradition that reef-net technology was a dowry given to Straits Salish people. Each species of salmon had a descriptive name such as ŧəqiʔ for sockeye, as well as a specific kinship term to be used as a form of address. Kinship terms and first-salmon rites varied among Coast Salish communities, but one widely shared element was burning Lomatium nudicaule seeds, widely used medicinally for people, as medicine for the salmon.

To go to Part 2, click "Next Feature"