A 1967 proposal to build a seven-story, 168-unit condominium on a 480-by-100-foot concrete platform to be constructed above the waters of Lake Union at the foot of East Roanoke Street in Seattle's Eastlake neighborhood touched off a 13-year legal battle as the neighborhood's houseboaters and upland residents fought to protect the lake's shoreline, houseboats, water-dependent businesses, and views. The ultimately successful battle against the proposed Roanoke Reef Condominium led to the formation of the Eastlake Community Council (ECC), which remains active in the neighborhood, and to a precedent-setting legal decision. Longtime Eastlake resident and business owner Jules James originally wrote this account of the Battle of Roanoke Reef in 1987 for an ECC fundraiser, and an updated version appeared in the summer 2021 edition of ECC's Eastlake News marking the group's 50th anniversary. It is presented here with permission.

The Battle of Roanoke Reef

It is the Seattle land-use fight by which all others are judged. Thirteen years, from 1967 to 1980, dozens of public hearings, and file cabinets of lawsuits concluded in victory for the neighborhoods of Lake Union.

Since 1962, neighborhood activists had warned that zoning loopholes could allow massive office and residential buildings along the shorelines and above the waters of Lake Union -- replacing houseboats and water-dependent businesses. State and city governments lent a deaf ear to the threat.

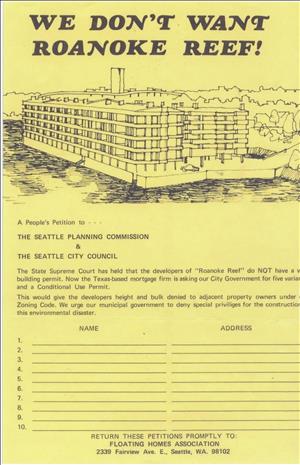

In 1967, neighborhood fears were realized when a building-permit application for a seven-story condominium was filed for the foot of East Roanoke Street. Existing were pleasure-craft moorages -- some covered, some not -- spread out around the Riviera Marina that housed Bill Boeing's weathered 1916 Seaplane Station. The proposed "Roanoke Reef Condominium" was to be built on a 480-by-100-foot concrete platform located just north of East Roanoke Street -- just above the waters of Lake Union. The application read: one story of concrete parking garage, then six stories of wood frame with stucco face and tinted-bronze glass. It boasted a heated pool, glass-enclosed lanais, television security system, three elevators, and 168 luxury units.

Houseboaters and upland neighbors rallied against the proposed project and won outright. The 1967 building permit for the Roanoke Reef Condominium was denied. But the battle of Roanoke Reef wasn't over; in fact it had only just begun.

In 1969, Fairview Boat Works just north of the foot of East Lynn Street was demolished and construction began on a five-story, 98-unit over-the-water apartment house (now the 48-unit Union Harbor Condo). Union Harbor was permitted and built before neighbors could organize meaningful opposition. Within months, five more proposals to build mega-unit over-the-water apartment houses along Fairview Avenue East were announced. A speculative feeding frenzy had begun, and Roanoke Reef re-surfaced as a five story, 112-unit condo proposal.

The newly formed citywide citizens group CHECC (Choose an Effective City Council) prodded state and local government to address the problem of Lake Union's inadequate zoning, and zoning loopholes were eventually closed in such a way as to discourage four of the five over-the-water development plans. One permit was issued, however, to Roanoke Reef. The permit application was submitted to the Seattle Building Department on May 7, 1969. It was "conditionally issued" the next day. Building permits were either approved or denied, so to neighbors the permit spread a strong stench of impropriety. In the end the battle of Roanoke Reef centered on what would turn out to be an illegally issued building permit.

Eastlake Community Council

Since individual plaintiffs could be held personally liable for construction delays while officers of nonprofit corporations were protected, a first legal strategy was the creation of a nonprofit community organization for upland residents. The Eastlake Community Council (ECC) was formed in 1971. Among its official purposes was (and still is) "to maximize public use and enjoyment of the inland waters and shorelines adjoining the Eastlake community." ECC worked with the Floating Homes Association (FHA, founded in 1962) to fight the vested permit. But each time the building permit was set to expire, the City renewed it.

Enactment of the 1971 Shoreline Management Act (SMA) should have ended the project outright. But "construction" on Roanoke Reef began March 15, just weeks before the SMA's June 1 effective date, with workers driving 10 concrete pilings into the lakebed.

Although community SCUBA divers proved the pilings were haphazardly placed and certainly only symbolic, the City again renewed the building permit.

In a June 23, 1971, letter to the Eastlake Community Council's co-founder Phyllis Boyker, then-Mayor Wes Uhlman wrote, "I dislike the destruction of a valuable natural resource like this section of Lake Union for purely business interests. Unfortunately, however, there seems to be nothing which can done to halt the project. No building or zoning codes have been violated and no laws have been broken."

In July, real construction began. Existing moorages were torn out along with the March 15 pilings. The old Riviera Marina that included the original Boeing Company hangar was torn down, and 250 concrete pilings were driven into the lakebed.

Legal Action

With the start of that construction, the community took legal action. Harold H. "Hal" Green of the firm MacDonald, Hoague, and Bayless offered his legal services "at cost." By summer's end $11,500 had been raised toward a legal fund. On September 15, 1971, a lawsuit was filed in King County Superior Court on behalf of ECC, FHA, and Phyllis Boyker, who formed the lead as a directly affected upland resident.

Among the suit's charges were 1) the City had issued an illegal building permit in 1969, 2) the City had repeatedly renewed the illegal permit, and 3) the developers were not in compliance with the Shoreline Management Act.

The developers, represented by Robert Ratcliffe of Diamond and Sylvester (the law firm of Joe Diamond, parking lot magnate) quickly brought a counter-suit against Phyllis Boyker. Under the threat of financial ruin, Ms. Boyker was forced to withdraw. The developers then contended that FHA and ECC were not directly impacted by the proposal and thus had no right to sue. The State Department of Ecology joined ECC and FHA as a co-plaintiff on February 10, 1972. The trial began four days later. After nine days of testimony, the introduction of 137 exhibits, and ten minutes of consideration following final arguments, Superior Court Judge W. R. Cole ruled against the community on every count -- including the very right to bring the lawsuit.

The ECC and FHA were exhausted, debt-ridden, and facing an appeal deadline to the state Supreme Court. They needed an additional $8,000 for transcripts and court-ordered bonds. They raised money through dances, rummage sales, spaghetti dinners, boat outings, door-to-door solicitations, and mailings. On April 19, 1972, in a meeting with representatives for the Attorney General's office (the AG at that time was Slade Gorton, a charter member of CHECC), the earlier promise of state help was negotiated into meaningful support. That evening, the votes were won to commit ECC and FHA to appeal to the state Supreme Court.

Meanwhile, back at the Reef, construction continued. A fully furnished model unit stocked with sales brochures opened at the adjacent construction staging area. A Roanoke Reef advertising billboard appeared in South Lake Union at the corner of Fairview Avenue N and Valley Street.

Precedent-setting Victory

On September 6, 1972, the Attorney General filed papers with the state Supreme Court to halt construction of Roanoke Reef. When work stopped, a significant portion of the cinder-block parking structure had been completed. Oral arguments were heard on November 13, 1972, before the state Supreme Court. Joe Diamond, himself, argued for the developers; Harold Green and Francis Hoague (a local liberal legend) for the community. On July 18, 1973, the state Supreme Court ruled for the community. The City was stuck with a nearly $3 million bill for illegally issuing the permit. What's more, the Court ruled that ECC and FHA did have standing to sue; an important early precedent for public-interest litigation that spread throughout the country.

But victory in a land-use battle does not simply come with a "permit denied" ruling, and developers do not just go away. In this case, the verdict did not include an order to remove the illegally permitted concrete platform. Within four days, the developers submitted a new building-permit application. The proposal had been reduced to 81 units, but remained 57 feet high. And in November 1973, the developers filed a $7,000,000 damage suit against the City of Seattle.

Although the developers eventually won a $2,896,534 judgment against the City (check written July 3, 1976), they made little headway in securing permits for their condominium. The tide of the Battle of Roanoke Reef clearly had turned to favor the community. Just before Christmas 1974, the City denied a final new building permit. The Roanoke Reef over-water condominium project was dead. During the next three years, occasional rumors circulated that a new condo building permit was soon to be submitted but the rumors always proved to be negotiation posturing or unfounded speculation.

Between 1975 and 1978, the Battle of Roanoke Reef was a miserable, tedious stalemate. The community was unyielding in seeking removal of the illegal platform. Removal was completely unacceptable to the developers. Sketchbook entrepreneurs offered ideas for a public park, marina, or restaurant to settle the celebrated dispute. Each scheme rested atop the illegal concrete slab. Most met with initial public approval. All required vigorous repudiation by the community.

In 1976, '77 and '78, the developers submitted land-use applications to establish marinas beside the platform. In each instance, the developers refused to state that further development would not occur. Two of the three proposals met with initial government approval. An attitude of "let's approve it and move on to another issue" seemed to prevail. But for the community, the platform continued to be illegal and developers refused to disclaim thoughts of future high-rise development. Each marina proposal initiated another round of public hearings. Each marina proposal was eventually defeated.

Like weeds through the sidewalk, life slowly began to infest the Reef's concrete slab. An impromptu marine-engine repair shop located there. Fishing boats tied up for off-season moorage. Some live-aboards took advantage of the $1 per foot moorage fees. Kids dove off the slab and canoes cruised under it.

End of the Battle

In 1978, the Roanoke Reef stalemate was broken and a temporary truce was declared. It was agreed that a City-hired consultant conduct a study of the legal, economic' and environmental ramifications of the concrete slab. The community supported the study only after demolition was included as an option.

Soon after the consultant's report, Lucile Flanagan (later the benevolent owner of the Crest Theater) quietly emerged with a viable Roanoke Reef plan. Ms. Flanagan would purchase the property for $500,000, demolish the concrete slab, construct and sell 20 condo houseboat moorages, plus nine townhouses at the site of the former construction staging area. The sale was finalized in the summer of 1979 and the Environmental Impact Statement completed during the first months of 1980.

No single individual led the community's efforts. Only houseboater Terry Pettus (FHA Executive Director) and uplander Victor Steinbrueck (an ECC board member) were intimately involved from beginning to end, but they thought it proper that the Battle of Roanoke Reef be spearheaded by the ordinary folks of the FHA and the ECC. Nine ECC presidents served during those years. The long casualty list of cancelled vacations, lost career opportunities, and strained family relationships explains the rapid turnover.

On a sunny Saturday -- July 26, 1980 -- the Battle of Roanoke Reef officially ended with a neighborhood party on the concrete platform. Food, music, beverages, skydivers, politicians, and speeches accompanied this latest of innumerable fundraisers for the ECC Legal Defense Fund, with one and all invited to start the demolition of the slab at one-dollar-a-whack.

A submerged reef of concrete is located somewhere off Blake Island where the remains of the platform were finally hauled to rest, but not before a few souvenir chunks were given out. For many years thereafter (it may be there still), on a shelf in the Director's reception area for Seattle's Department of Construction and Land Use there was a chunk with an engraved red aluminum label reading "Roanoke Reef, 1971-1980."