In 1952, a Wenatchee junior high school principal asked English teacher and circus aficionado Paul K. Pugh to put together a tumbling team that could entertain crowds during school sporting events. Pugh assembled a troupe that started practicing flips, somersaults, and other tumbling routines, and soon expanded its repertoire to include tightrope walking and trampoline feats. The one-ring show became known as the Wenatchee Youth Circus. Pugh, who died in 2016, was its only adult performer, donning a mismatched outfit, orange wig, and face paint to turn into Guppo the Clown. Within a decade, the Wentachee Youth Circus was getting coverage in national magazines such as Life and the Saturday Evening Post, and in 1962, the troupe performed for a week at the Seattle World's Fair. Some of its alumni went on to professional circus careers, performing with Cirque du Soleil, Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey, and the Flying Wallendas.

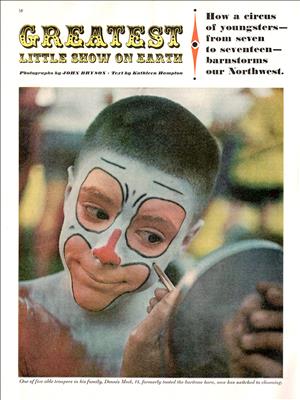

The Greatest Little Show on Earth

The Wenatchee Youth Circus was started in 1952 by Paul K. Pugh (1927-2016), a junior high school English teacher in Wenatchee who was asked by his principal to create a tumbling act that could perform at school events and games. Before long, the tricks had expanded to include tightrope walking, trampoline, aerial bars, and juggling. As it expanded its acts, the troupe shifted location to the YMCA and became known as the Wenatchee YMCA Circus and later, the Wenatchee Youth Circus.

In these early days the circus included animal acts: monkeys, dogs, a horse, even a boa constrictor named Bessie. But keeping the pets safe and cared for during the off-season was a challenge. "Unhappily the circus has had less than glorious success with the few animals it has tried to keep," The Saturday Evening Post reported in 1962. "Most fondly remember a baby baboon named BoDee, who survived the affection of seventy-five owners for one season, then accidentally hanged himself just before a performance in Lewiston, Idaho. The youngsters sadly went through with the show, then buried him behind home plate at the ball park" ("Greatest Little Show ..."). Soon animals were dropped from the list of performers. Joked Pugh: "[We] retained the most dangerous animal of all, and that's teenagers" (Wright).

The Wenatchee Youth Circus worked with children of all ages, even as young as 1 year old. High-wire walkers might perform at age 7, and flying trapeze artists could be 8 or 9. Pugh once said: "We take anybody who's interested. ... If a child wants to join the circus, we'll have a place for them if they have their parents' permission. ... We invite parents to join them because it's a family experience" (Wright). Children under 12 had to travel with a parent on tour, and having parents involved was handy because the adults could provide much-needed services such driving the trucks, moving heavy equipment, catering lunch for the performers, or serving as chaperones. Costs were kept low, under $50 per year per family, enabling the participation of many who otherwise could not afford acting, singing, or dancing lessons.

Although most of the performers lived in Central Washington, others came from neighboring states and even as far away as Australia. The out-of-towners were asked to attend trainings during the school year and then commit to touring with the circus for several weeks in the summer. They spent the after-school hours in the winter training; the summer months were spent on the road entertaining communities large and small.

Most of the students learned a lot more than just acrobatics or fire-eating tricks. "The circus teaches responsibility, respect and teamwork, [Brandon] Brown and [Meghan] McLean, 18, said. It requires a huge commitment of time. Being able to take constructive criticism is important, McLean said. 'You gotta laugh at yourself,' she said. 'You gotta make fun of yourself to keep going'" ("Visiting Youth Circus ..."). When Stacie Soth first joined the circus in 1971, "she didn't think she could do anything. Now she can eat fire and knock down paper cones with an 8-foot bull whip. 'The circus really gives you self-confidence,' Stacie said after her performance yesterday. 'You see that there are all kinds of things you can do'" (Sullivan).

In 1980, Don Williams parlayed his experience with the Wenatchee Youth Circus into a career as a professional clown with the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus. Pugh had noticed the boy's performance in a seventh-grade school play and invited him to try out for the circus. Declaring he had "sawdust in my blood" (Zoretich), Williams toured during the summers and spent his winters perfecting his clown routines. When he turned 18, he auditioned in Seattle for the Ringling clown college in Sarasota, Florida; he was the only one from the Seattle tryouts that year to be accepted into the nine-week program. His talents also attracted an offer from the Wallenda family circus, which he turned down. Williams later said: "The best thing about being a clown is that it keeps my attitude positive. ... As you perform you can't help but enjoy yourself because of what you're doing. ... What's my next move? Now that I'm with the greatest show on earth, what could be better? Is there a circus in heaven?" (Zoretich).

Seattle World's Fair

By the early 1960s, Life magazine had run two features on the youth performers. The February 3, 1962, issue of The Saturday Evening Post, in a spread that "dominated the magazine" ("Y Circus in Top Story ..."), devoted six pages and seven color photos, two of them full page, to the circus. The Post writer was Seattle-based Kathleen Hampton, who had traveled with the group in Oregon the preceding summer. Photographer John Bryson interrupted his assignment in Hawaii to fly to Wenatchee for the shoot. The story began:

"A spotlight glints on a steel wire thirty-five feet above a playing field in Roseburg, Oregon, then follows the wire slowly through the darkness. The crowd gasps as the light stops at the figure of a tiny girl poised on a pedestal. 'Ladeeze and gentlemen! You are about to see the youngest high-wire walker in the world.' As the words of a towheaded young ringmaster reach the bleachers, a frantic blast of sixteen circus horns introduces a member of the remarkable Wenatchee Youth Circus. From the seven-year-old high-wire walker to the seventeen-year-old boy on the flying trapeze, these are ordinary small-town youngsters who every summer become part of the magic world of wailing calliope and dancing clowns. Rolling into Northwest farm towns in a bright-red caravan -- an old school bus and three ancient trucks -- they set up secondhand circus equipment in a ball park or football field and put on an open-air show that would astonish three-ring professionals" ("Greatest Little Show ...").

From July 15-22, 1962, sixty Wenatchee Youth Circus performers appeared at the Seattle's World Fair. They were on the bill with Huckleberry Hound and Yogi Bear in the Century 21 (Memorial) Stadium, performing two shows a day. The troupe completed fifteen acts in about an hour, an abbreviated version of its regular summer show, which ran about two hours and included twenty-five acts. The Saturday Evening Post noted that the circus had traveled more than 40,000 miles in the past decade, thrilling about 75,000 spectators a year.

In 1965, the group got a two-page spread in Sunset magazine, appearing under the headline, "The Greatest Little Show on Earth." That year, the troupe numbered 85 and the average age was 15. On June 6, 1965, the youngsters performed in Seattle at the Coliseum in what was called a "real live rip-snorting circus" ("Wenatchee Youth Circus"), with colorful costumes, breathtaking high-wire performances, and the distinctive dissonance of a steam-driven calliope. After the matinee was over, the performers hurried back to Wenatchee to take their final exams.

Safety First

By the 1980s the Wenatchee Youth Circus had become a tightly organized road show, according to a March 1986 story in Boys' Life magazine:

"Today when the circus hits the road, everyone rides in two charters buses. A 40-foot flatbed truck carries eight circus wagons with scarlet lettering and gold curlicues. One wagon opens out to make a bandstand with lights. Two are kitchen wagons from which mothers serve hot meals for 125 (including parents who help backstage, and guests). The other five are packed with a portable generator and lights, rigging, sleeping bags, big tents for dressing and eating, and 20 trunks of bright spangled costumes. All this equipment is valued at $95,000" ("They Put Their Show ...").

By 1994, the circus was averaging 12,000 miles a year on tour. The number of youth performers averages about 50, although some years it dropped as low as 16. Most of the very youngest started out as clowns or were at the top of a human pyramid act. The older students did it all, from trampoline to high wire.

Safety was of paramount concern, but the acts were not as dangerous as they appeared. "There are nets under the trapeze and high wire, and spotters. The performers are reminded constantly to check their equipment before they start their acts 'just like the real circus'" (MacDonald). After 52 years in existence, however, the circus lost one of its performers in a tragic accident. In July 2004, 18-year-old Shawn Thomas was guiding a wagon off a flatbed truck in Grant County when the wagon veered and rolled over him. A gifted athlete, Thomas had just graduated from Eastmont High School. He had been with the circus for 11 years and participated in many acts, from tumbling to trampoline, and fire-eating to Roman ladders.

Media coverage whips up each summer as the circus gets ready to tour. In 2017, the troupe was featured on PBS NewsHour and in Teen Vogue magazine and was invited by the Smithsonian Institution to perform in Washington, D.C., as part of the two-week Smithsonian Folklife Festival. In late June and early July 2017, 13 members of the circus spent two weeks on the National Mall, where they performed in front of an estimated 1 million people.

Touring is still quite a production today: The entourage travels with a bus, two trailers, and three trucks. But trucks and trailers were quiet during 2020 and 2021 as the pandemic played out. In 2021, the circus began recruiting performers again with the hopes of scheduling a 2022 tour season. The Wenatchee Youth Circus is a nonprofit organization that operates largely with grants. Service groups such as the Kiwanis and Rotary Club help with fundraising, sell tickets, provide extra manpower to stage the show, and publicize performances in their local communities.

Circus Founder Paul Pugh

Paul K. Pugh was born in Wenatchee on June 26, 1927, to Genevieve (1905-1988) and Lloyd Keith Randolph (1904-1978). His mother married Arthur Job Pugh (1892-1961) in 1934 when Paul was in first grade, and he adopted his stepfather's last name when he turned 16. In 1940, the family moved to Seattle, and Paul graduated from West Seattle High School in 1945. After serving in Korea and working in the Armed Forces Radio Service, he entered Whitman College in Walla Walla on the GI Bill. While at Whitman, he performed as a guest clown with the Clyde Beatty and Christiani Brothers circuses when they came to town.

Pugh graduated from Whitman in 1951, and then began teaching social studies and language arts at H. B. Ellison Junior High School in Wenatchee. He later earned his master's degree. His thesis subject? The circus.

Pugh later transferred to Orchard Junior High School, where he served as vice principal, and then principal from 1964 to 1982, when he retired. He married Katherine (Kay) in 1948 and the couple had three children: David, Jon, and Margaret. In 1975, he married Karen Sue Peart (1942-2018) and inherited a second family, daughter Darcy and son Terry.

Like many of his circus students, Pugh was a born performer. He was a radio announcer in his youth and sang in the church choir. He enjoyed acting, with favorite roles including Harold Hill in "The Music Man" (1972) and Haj in "Kismet" (1978).

Pugh was the only adult performer with the youth circus, donning the outfit and taking on the persona of Guppo the Clown. His son David explained that the name was partially based on rearranging the letters of the family name. As Guppo, Pugh's transformation included an orange wig, white face paint, a red-and-white striped shirt, and a baggy checkered vest. In his later years, Guppo sported a colorful striped cane.

As the founder and director of the Wenatchee Youth Circus, Pugh received many awards. In 1963, the Wenatchee Chamber of Commerce presented him with the Golden Apple award for his outstanding community service. He also received awards from Boy Scouts of America and Whitman College. In 2003, a sculpture of Pugh as Guppo was installed in front of the Wenatchee YMCA; Pugh had trouble holding back tears during the unveiling ceremony.

Wenatchee Mourns

Pugh died on January 31, 2016, at the age of 88 of complications from a broken hip and dialysis treatments. His family arranged a community memorial service on February 27, 2016, at First United Methodist Church. "Many fans thought it'd be appropriate for Paul Pugh, aka Guppo the Clown and founder of the Wenatchee Youth Circus, to die at center ring in full costume – orange wig, red bulb nose, big smile. 'That's the spot he loved the most,' said Karen, his wife of 40 years. 'I always suspected he might go out that way – in the spotlight'" (Irwin).

As an educator, community booster, and circus director, Pugh had touched thousands of lives, and the outpouring of affection and respect was overwhelming. "The accolades and expressions of gratitude flowed like the Wenatchee in spring. They came in such numbers the editors had to divide them into installments. They came from Youth Circus alumni, from former students, from friends. If our lives are judged by the number of people we helped, Pugh's reward will be rich indeed" (Warner).

At his memorial service, the church was packed with circus alumni, former students, family, friends, and colleagues. Reflecting on his father's death, David Pugh, who himself had been a clown in the Wenatchee Youth Circus from age 3 until 11, said: "Dad was a cross between the Pied Piper of Hamlin and the Music Man. ... Circus comes from the word 'circle,' so older kids teach younger ones, and there's always that sort of brotherly camaraderie. It's this magical forum where you learn to get along with others and to solve little mini-crises and everything comes together somehow" (Kim).