In the mid-1970s, civil rights advocates painted a red line on the street in Seattle's Central District, running along 14th Avenue from Yesler Way north to Union Street. The protest action aimed to dramatize a longstanding grievance: redlining. Redlining was a discriminatory practice that restricted where people could buy or rent residences based on their race and ethnicity. Banks, mortgage companies, and others refused loans for property transactions to people of color in specific neighborhoods covering large swaths of the city. Redlining promoted housing segregation in tandem with racially restrictive covenants in deeds and plats, plus realtors' practices of limiting where they showed properties for purchase or rental to non-whites.

Neighborhoods, Outlined in Red

Seattle has a long history of redlining and other forms of housing discrimination. As historian James Gregory of the University of Washington has put it, "For most of its history, Seattle was a tightly segregated city, fully committed to white supremacy and the separation or exclusion of those considered not white" ("Seattle Segregation Maps"). Ending racially based practices in real estate took an arduous fight that continues today.

The roots of discriminatory practices in Seattle housing extend to the early 1900s, when racially restrictive covenants became common. The covenants served as a main pillar of segregated housing. They came into popular use after a 1917 U.S. Supreme Court ruling (in Buchanan v. Warley) found city segregation ordinances violated the 14th Amendment. So, adherents of housing discrimination turned to covenants – agreements whereby a group of property owners, subdivision developers, or realtors were bound not to sell or rent their property to specified racial or ethnic groups. In 1926 the U.S. Supreme Court (in Corrigan v. Buckley) found these covenants were lawful because they involved individuals entering into agreements of their own volition, rather than action by government.

The language of restrictive covenants was far from subtle. A typical one, found in many deeds in Seattle's Queen Anne neighborhood, read "No person or persons of Asiatic, African or Negro blood, lineage, or extraction shall be permitted to occupy a portion of said property." The covenants were quite effective, as any owner who violated a racial restriction could be sued and held financially liable.

Seattle's first known restrictive covenant was written in 1923 by the Goodwin Company, applying to three of its tracts slated for development in the Victory Heights area in north Seattle. The University of Washington's Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project, which conducted extensive research on the issue, found several hundred such covenants and deed restrictions in the King County Archives. Most were written by real estate companies and land developers, including Seattle icon William E. Boeing, owner of a large tract of land to be developed.

As for older areas which were already developed, some homeowners kept out nonwhites by adding racial restrictions to existing property deeds. Nearly a thousand owners on Capitol Hill, for example, did so as part of a coordinated campaign in the late 1920s.

Rampant Discrimination

Restrictive covenants from the 1920s to the 1940s barred non-whites and sometimes Jews from residing in North Seattle, West Seattle, and some parts of South Seattle, Capitol Hill, Queen Anne, and Madison Park. The resulting ghetto ran east from the International District and north from South Jackson Street. This left the Central Area and the Chinatown International District as the neighborhoods open to African Americans and Asian Americans.

A census map of 1920 illustrated the segregation starkly. The census tract with the heaviest concentration of African Americans, in the Central Area, showed 450 African American residents. No census tract north of the Ship Canal or in West Seattle had more than 25 African Americans living there.

A 1948 U.S. Supreme Court ruling (in Shelley v. Kraemer) found that racially restrictive covenants were not enforceable by law. But they could still be established and enforced privately, by social mores. So, housing discrimination persisted. For example, longtime King County Council member Larry Gossett recalls that when his father wanted to buy a house in West Seattle in 1956, a realtor told him she would be "run out" if she tried to help him do so. Around that time, a Jewish refugee from Austria abandoned his effort to buy a house in Sand Point after he received repeated threats from a neighborhood leader.

Roots of Redlining

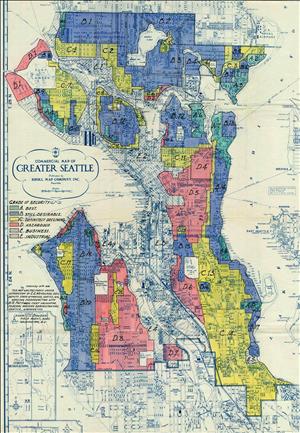

"Redlining" as a term has its roots in government efforts to buttress faltering housing markets during the Great Depression. In the late 1930s the federal Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC) undertook a project to evaluate mortgage risks in cities across the country. It rated neighborhoods as "best," "still desirable," "definitely declining," and "hazardous." The idea was that by showing lenders neighborhoods that were good bets for mortgages, lenders would be encouraged to actually make loans.

Neighborhoods deemed financially risky were marked in red – whence the term "redlining" – and lenders were discouraged from financing property transactions there. In practice, this promoted racial inequality because the neighborhoods boundaries were often drawn along racial lines. The HOLC maps show where the accepted standards at the time were already deeming mortgages a risk, and the federal agencies did not challenge, counteract, or stop those discriminatory standards.

In Seattle, the Central Area was described as a place of homes "generally old and obsolete, in need of extensive repairs" ("Confidential Report, 1936 ...") -- that is to say, a "hazardous" neighborhood where extending mortgage loans would be risky. People of color clustered in the redlined Central Area found it very difficult to get housing loans. It was a classic formula that prevented Blacks from accumulating generational wealth by limiting their ability to own homes in the neighborhood where they could live.

Many realtors clung to an unproven belief that integration in housing would hurt property values. When an ordinance against housing discrimination was proposed in Seattle in the 1960s, real estate leaders opposed it as "forced housing" that would undermine personal freedom. Apartment building owners and real estate industry representatives denounced such measures in florid language as "dictatorial, confiscatory, and would lead to evasion and disrespect for the law" (The Seattle Times, 1961, quoted in "The Seattle Open Housing Campaign, 1959-1968").

Resisting Segregtion

However, organized resistance to housing discrimination emerged. Leading the way were African American civil rights organizations including the Urban League and the NAACP, religious groups, and liberal-minded white organizations. These opponents of segregation advocated for "open housing" – that is, requiring that property transactions take place free of restrictions based on race. In 1962 an advisory committee appointed by Mayor Gordon Clinton (1920-2011) recommended adoption of an open housing ordinance. After action was delayed, 35 young people from the Central Area Youth Club occupied the mayor's office, and Reverend Samuel McKinney (1926-2018) of Mount Zion Baptist Church in the Central Area organized a march on City Hall.

But white Seattle was not yet ready for desegregation. In 1964 the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) sent Black and white individuals to view the same rental apartments. They found that landlords almost never offered an apartment to a Black would-be renter. That same year, Proposition 1, an ordinance banning racial discrimination in real estate sales and rentals drafted by the new Human Rights Commission, appeared on the ballot. Voters citywide rejected it by a more than 2-1 margin.

Nevertheless, the civil rights movement of the 1960s did spur change. In 1965 the Seattle Real Estate Board announced a new policy that members were to show all listings without discrimination. Racial uprisings in Los Angeles, Detroit, and elsewhere raised fears among white leaders that racial tensions could explode in Seattle. In April 1968, three weeks after Martin Luther King Jr.'s assassination, the Seattle City Council unanimously passed an open housing ordinance. Its architect was Sam Smith (1922-1995), the first African American to sit on the Council. That same year, Congress passed the Fair Housing Act of 1968 which barred the enforcement of restrictive covenants both under the law and by private means.

"Banks are Destroying our Neighborhoods"

But discrimination in real estate persisted via other means. In 1975 the Central Seattle Community Council Federation published a report starkly titled "Redlining and Disinvestment in Central Seattle: How the Banks Are Destroying our Neighborhoods." It detailed practices in the Central Area and Rainer Valley by which banks fostered inequality by refusing to lend money on properties that fell below a certain price. It also showed that ratios of bank deposits to loans were far lower in the Central Area than in Seattle's suburbs – that is, money from its residents was not being reinvested in their community.

In response, Mayor Wes Uhlman (b. 1935) and two City Council members announced formation of a task force to examine investment practices regarding houses and businesses. In testimony before the Council, Rev. McKinney recounted how Seattle banks repeatedly turned down his Central Area church for loans for a new sanctuary. It was, he said, "… just another attempt, we felt, on the part of the white system to keep black and other poor people from trying to achieve their dreams" ("Redlining in Seattle," Frantilla).

In 1976 Uhlman announced a new voluntary Lenders Review Board that enabled people to appeal denial of loan applications by eight participating lenders. Its operations were the subject of controversy. Citizen activist Margaret Ceis criticized the body for "meeting in the board rooms of banks and the downtown Chamber of Commerce where lower-income people might not readily go" ("Redlining in Seattle," Frantilla) and for resorting to private executive sessions. R. J. Vanek of the Seattle Coalition on Redlining observed that as a result of his challenging the body's procedures, "When I first attended the meetings, I was as welcome as a skunk at a picnic" ("Redlining in Seattle," Frantilla).

A Lasting Legacy

All the activism had put the need to address discriminatory housing practices on the public agenda and fostered long-sought-after change. In 1977 the Washington State Legislature passed HB 323, a measure making it unlawful for a financial institution to deny or vary the terms of a loan because of the neighborhood a property is in. Redlining as a policy was finished by the end of the decade.

Vestiges of discrimination remained in clauses in many property documents, though. So, in 2006, Governor Christine Gregoire signed a measure, SB 6169, which made it easier for homeowners' associations to get rid of racially restrictive covenants. In 2018 the Legislature added a provision enabling property owners to strike racial restrictions from deeds and other property records.

The long era when housing discrimination was overt and pervasive left a significant legacy after discriminatory practices themselves ended. The areas most affected by loan refusal and lack of investment remained African American and continued to have depressed real estate values for many years, until prices began to rise and gentrification displaced the lower-income families who lived in the neighborhoods. Decades of denied home ownership and depreciation of home values left community members with little of the equity that would have allowed them to benefit from the rising property values or to continue to live in gentrifying areas.