Cheryl Linn Glass was the first African American female professional race-car driver in the United States. Growing up in Seattle, at the age of 9 she started her own doll business and also began driving quarter-midget race cars. Graduating from Nathan Hale High at 16, she attended the University of Washington and then Seattle University. At 18, she became a professional race driver, racing at Skagit Speedway in Mount Vernon, Skagit County. Over the next two decades, she raced in more than 100 events throughout Washington and around the country, accumulating trophies and awards, with the goal of racing in the Indianapolis 500. Glass also opened and ran a wedding design studio and catering service in Seattle's Pioneer Square. In 1997, Glass's body was found in Lake Union below the Aurora Bridge. Her death was ruled a suicide.

Family Background

Shirley Ann Robertson (b. 1936), Glass's mother, was born in Nashville, Tennessee, to Norman and Helen Thomas Robertson. She attended Tennessee Agricultural and Industrial State College (later Tennessee State University-TSU).

Glass's father, Marvin Edward Glass (b. 1935), was born in Ridgley, Tennessee to Porter (1916-1984) and Florence Bonds (1917-1995) Glass. His family moved to the small Tennessee town of Dyersburg on the Mississippi River when he was a young child. Marvin also attended Tennessee Agricultural and Industrial State College.

Glass's parents married on November 27, 1957, during their studies at TSU. Marvin and Shirley both received electrical-engineering degrees on June 1, 1959. Shirley accepted a position at the Boeing Company in Seattle and the ambitious young couple packed their belongings and relocated to Washington.

Early Childhood -- Start Your Engine!

The Glasses settled at 1201 S Cloverdale Street in Seattle's South Park neighborhood. Shirley Glass began working at Boeing on June 22, 1959, as an electrical engineer. She may have been the first African American female engineer at Boeing. The couple moved briefly to California sometime before 1961, living at 1779 Welch Avenue in San Jose. Shirley still worked at Boeing and Marvin at Lockheed.

Cheryl Linn Glass was born to the upper-middle-class couple in Mountain View, California, at El Camino Hospital, the day before Christmas on December 24, 1961. The family moved back to Seattle by 1963. The couple would have another daughter, Cherry (Sherry) L. Glass (b. 1971), a decade after their first.

By the age of 3, Cheryl Glass demonstrated reading and writing skills. Her parents enrolled her in the Evergreen School for Gifted Children in Shoreline when she was 4. While attending school, she took an I.Q. test and scored 151. She learned to cook and sew when most children learn how to set a table.

Her parents poured love, encouragement, and support into their first-born daughter's interests. In 1983, Glass told The Seattle Times:

"My parents put me in many activities and encouraged me to pick what I wanted to do. They told me I could do anything and never to let anybody stop me" (Rhodes).

When she was 6, her mother enrolled Glass in the Bon Marche Cinderella Modeling School. She modeled in a variety of shows hosted by Bon Marche stores until 1969. At 7, she began her lifelong love affair with crafts, and ceramic artistry, to which she was introduced by her mother. Glass attended the private Bush School in Seattle from 1968 to 1975. Her mother became an active parent in school activities.

While Cheryl was discovering her talents and interests in a sea of opportunities, her father was appointed on July 24, 1969, by Washington Governor Dan Evans (b. 1925) to the Board of Trustees of Seattle Community College (SCC). The appointment, which made Marvin Glass, then a well-known engineer for Pacific Northwest Bell, SCC's first African American trustee, followed months of protests over discrimination at the college. Glass succeeded banker Carl Grunewald Dakan (1914-2003) on the board.

In 1970, at the tender age of 9, Glass started a doll-making business called Cheryl's Ceramics. Her high-end, hand-crafted, lifelike painted ceramic dolls were right out of the 1800s. They were sold to local businesses such as Frederick & Nelson. It took a month to sew the dress, paint the figure, and fire it.

The asking price for her classic dolls ranged from $150 to $300 each. As demand grew, Glass switched from ceramics to porcelain at prices ranging from $250 to $500 per doll. These dolls illustrated the kind of talent, ingenuity, and meticulous skill that wowed Glass's admirers.

First Races

Even as she started the doll business, the little girl was about to embark on a major transition in her life. Reading a newspaper article about local kids driving quarter-midget (go-cart) cars sparked her interest. She was not familiar with the sport of driving cars, but was intrigued enough to explore. With her parents, she went out to a track to view racing.

When she expressed interest in race-car driving, her parents, although also unfamiliar with the sport, encouraged their daughter to pursue it. Glass purchased her first quarter-midget car with assistance from her father and money she earned from the doll-making business.

Soon she began racing quarter-midgets with other children for the Washington Quarter Midget Association, the Little League of auto racing, at Everett's Paine Field near Mukilteo. Glass was often the only female and African American racing. In her first year of competing, she was the first female to be named Rookie of the Year by the association. That was just the beginning.

Glass competed in many state and regional championships and placed as one of the top 10 drivers in the country. While competing she continued to manage her doll business and attend school at Seattle's Meany Middle School (1974-1975) and Jane Addams Junior High (1975-1976).

Her mother, an immense supporter, was always nervous about her daughter's racing. She was not one of those mothers who could cheer out loud or watch; she cheered inside herself with eyes closed. Even though her daughter was protected by safety equipment and gear, getting injured was a natural part of the sport.

For all her anxieties about her daughter being behind the wheel, Shirley Glass was an active parent in all aspects, as she noted in a 1981 interview: "You might say we're a racing family ... It takes up much of our time and resources, but it's fun" (Green).

In 1977 at the age of 39 Janet Guthrie (b. 1938) became the first woman to qualify and compete in the Indianapolis 500. She never won the race. At the time, Glass was a not-so-typical teen with the intent to drive in the Indy 500 and win; then, once that was accomplished, compete as a Formula One driver.

It was an ambitious goal coming from a young girl who played with dolls one minute and then got interested in race-car driving. To compete successfully in the Indianapolis 500, Glass would need to get more experience racing on pavement and acquire strong financial support.

A Pro on the Go

In August 1978 Glass graduated from Nathan Hale High School with honors at the age of 16. That September she started at the University of Washington as a pre-med student, later switching to engineering. In 1979, she started appearing on television discussing her skills as a race car-driver and artist, and life as a college student.

After nine years of amateur racing, she switched from quarter-midgets to half-midgets, then turned professional race-car driver at the age of 18 in January 1980. Glass formed the Glass Racing Team, the only black-owned professional auto-racing team in the nation at the time. The team consisted of Glass as president, driver, and co-owner; her father Marvin as vice president, general manager, co-owner, and self-taught auto mechanic; and Richard Allan Lindwall (b. 1957) -- who would become Glass's first husband -- as crew chief and head mechanic.

With a successful quarter-midget driving record throughout her teens, Glass filled a room wall-to-wall with a collection of more than 250 trophies, 300 other ribbons, and all kinds of awards. She also had six track records in several significant state and regional championships. Glass was nicknamed "The Lady" and "Lady Glass."

She attended the University of Washington until August 1980. The next month she transferred to Seattle University, majoring in general science and then engineering.

Glass had been in and out of the public eye for years and now she was ready to move to the next level of racing. The Pacific Northwest is sprint car country. The traditional route to the Indianapolis 500 was limited by her lack of sponsorship and need for more extensive driving experience. During the 1980s, she became obsessed with racing in the Indy 500.

First Crash

After two-and-a-half years of college, Glass left without earning a degree. The lack of a degree did not hold her back from the goal she wanted to achieve. Her focus was on pursuing race-car driving fulltime, beginning in the macho atmosphere at Skagit Speedway in Mount Vernon, some 60 miles north of Seattle.

In the speedway's 26-year history, Glass was the first African American women sprint-car racer. She soon became a crowd favorite and pride of Skagit Speedway. A young woman competing with men in a rugged sport makes for an interesting subject.

With her success in Washington, it was time for Glass to ventured out of state. She had an ambitious timetable, and soon graduated from the Bob Bondurant School of High Performance Driving at Golden State International Raceway in California.

On the evening of October 25, 1980, Glass, the Rookie of the Year at Skagit Speedway, was competing in the Western World Sprint Championships at Manzanita Speedway in Arizona. The 18-year-old raced at more than 120 m.p.h. strapped in a V-8 powered tube-frame vehicle, trying to pass several competitors on the high side of the sloping track.

She had a devastating crash, hitting the wall of the track, and was taken to Memorial Hospital. The petite, 5-foot-3-inch, 115-pound driver didn't break any bones, but she suffered major soft-tissue damage to her neck, back, and knees, requiring four knee operations to try to repair the torn ligaments. A nasty first crash!

Five years later, Glass told The Los Angeles Times:

"The back end got loose, slid around, smacked the wall and climbed a 20-foot fence ... The car started rolling along the fence. Thirteen times it went over and then it dropped back on the track and tumbled end-over-end ...

Once I realized I was still alive after all the bouncing around, I never doubted I would race again ...

Every time I'd watch the news on TV, they'd run replays of my accident" (Glick).

The crash did not deter her from her goal reaching the Indianapolis 500 but her career almost came to a smashing halt. The odds were against her but she was determined move forward.

Racing and More

As a member of the Florida World of Outlaws circuit, Glass started traveling extensively. While pursuing her career in racing, she also became a debutante, was nominated for the Seafair Princess Pageant as Miss Rainer Bank in 1981, graduated from the John Robert Powers Advanced Modeling School, and got involved in charity work and educational outreach. She graced the pages of publications such as Seventeen, Ebony, Essence, Jet, and others. Glass even managed to enter the Miss Lake City contest and finished in fourth place.

But racing remained a primary focus. She explained in 1981: "I'm my own person. Sure, it's different to have a black woman in auto racing. But ... I want my driving abilities to speak for themselves" (Green).

In 1981, she won the Northwest Sprint Car Association of the Year, beating Al Unser Jr. (b. 1962). Glass's sister Cherry raced quarter-midgets after watching her older sister compete, and won her fair share of races. Cherry would graduate from Seattle Pacific University at age 19 and train as a commercial airline pilot.

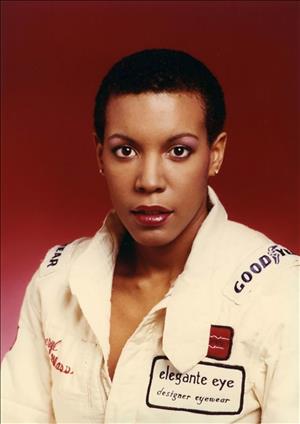

Cheryl Glass was able to gain some sponsors and media attention. Olympia Brewing Company backed Glass as did Elegante Eye, a Seattle eyeglass company. Elegante Eye owner Sally Kaye "created a signature pair of eyeglasses in Cheryl's name, blending style with sport, further cultivating the young racer’s image" (Steele).

Fred Brownfield, the first driver to capture both the Northwest Sprint Cars and Skagit Speedway Sprint Division championships in one season, acknowledged "he was bothered by the media attention" surrounding Glass:

"Yeh, a bit. I won two major championships last year and seldom does a reporter come around and talk to me ... She's a crowd pleaser and has been good for the sport ... She has helped attract women to the races, and the increase in attendance last season helped boost my winnings 10 percent. But there is also a number of people that enjoy seeing her get beat, too" (Green).

Glass was well aware of the conflicting opinions about her:

"At her [1982] campaign for the USAC Silver Crown in Indianapolis, she was asked whether her sex or her race had been a hardship or help. 'Both,' she said. 'Women aren't supposed to be sprint drivers and most men (back in the Northwest) really haven't liked me. Their attitudes have made it very difficult for me to race. But I've been accepted around the professional drivers ... I'm determined to prove I can handle it'" (Steele).

Opportunity and Another Direction

Glass was competing in the USAC Silver Crown, or Hoosier Hundred, after Charlie Patterson (b. 1937) from Indianapolis, who owned Patterson Driveshafts, reached out and offered her an opportunity. Patterson introduced her to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and tried to get her sponsorship. It did not happen. He used his own money to sponsor Glass. In a 2019 interview, Patterson recalled:

"She drove my silver crown car at the Hoosier Hundred ... It was quite an honor to go see her name on the car I built for her at the Racing Hall of Fame in Knoxville, Iowa" ("Life in the Fast Lane ...").

Patterson received national attention as Glass piloted his sprint car No. 12. She was credited with a 21st-place finish. It was the only race she drove for Patterson in their short-lived association. She went on to race in the Hulman Hundred Championship in Iowa and the Copper World Classic in Arizona.

Even as Glass was participating in a string of race activities, she was beginning to broaden her life yet in another direction beyond driving. On February 19, 1983, she married Richard Lindwall, the head mechanic on her auto-racing team, at Saint Mark's Episcopal Cathedral in Seattle.

Glass designed her own wedding dress and the bridesmaid's gowns. The elaborate wedding was described as the Seattle "wedding of the year" (Rhodes). Glass's unique wedding designs sparked the interest of other brides and requests came pouring in after the wedding. This soon led to her career as a fashion designer, even as she continued racing.

The marriage itself would be short-lived, ending in 1984. The couple had no children.

The Race to Indianapolis

With Glass unable to reach the Indianapolis 500 by 1983, her father purchased an older Penske PC-6 Indy car for her to test at the Seattle International Raceway, with sights now on Indianapolis in 1987. In the 1984-1985 school year, Glass was among 100 Washington women featured in a publication for elementary-school students that included sketches of women's many roles across the state. An accompanying set of 56 trading cards, designed to increase awareness of multicultural contributions in all areas of work, community, and homelife, also included Glass with photos of her racing.

On July 7, 1984, Glass entered the Sports Car Club of America Canadian American Challenge Cup (Can-Am) Series held at Fair Park in Dallas, Texas. Driving a Van Diemen 682 Volkswagen, she completed six laps and finished in seventh place. At 23, she was one of five women, and the only African American woman, on the professional race-car circuit in the United States. Her appetite for the Indy circuit kept increasing.

The Indianapolis 500, a huge event that traditionally brings in at least a quarter million spectators from across the country, is the centerpiece of the top-level car races known as the Indy Car circuit. To be ready for the Indy 500, Glass would need to race in a number of Indy Car races. Money for the expenses of racing would be a challenge, and she'd need a sponsor to promote her. They were not knocking at her door and she needed to think creatively to get support.

On May 23, 1985, Glass opened her fashion business, Cheryl Glass Designs. The peaches-and-cream-colored studio was located in the Interurban Building at 102 Occidental Avenue S in Seattle's Pioneer Square. She crafted bridal and evening gowns for special occasions locally and nationally. Glass also provided a full catering service handling wedding receptions, including sit-down dinners, flower arrangements, and music. She divided her time between racing cars and fashion and design.

Glass secured a contract with Adolph Coors Company, "doing promotional work ... [and] acting as a corporate spokesperson at ... meetings [and] conventions" (Glick). On July 18, 1985, Glass had a second racetrack crash while test driving a Coors-sponsored Toyota pickup truck in the Los Angeles Coliseum in preparation for the Off Road Grand Prix scheduled there three days later.

Glass would not get the chance to race in the event. She hit a rise off the straightaway and drove the truck into a hill. She was taken to Daniel Freeman Hospital in Inglewood, California. The X-rays taken were negative and Glass was released from the hospital hobbling with a sore right ankle. The crash was another setback to her Indianapolis 500 dream.

She took some long-awaited time off during 1986 to reset and engage in other activities. With her father, Glass co-founded the Minority Engineering Retention Program (later the Minority Science and Engineering Program) at the University of Washington.

On June 17, 1987, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, Glass was honored alongside others, including Coretta Scott King (1927-2006), at the annual Candace Awards, sponsored by the National Coalition of 100 Black Woman, as a trailblazer -- the only professional African American woman race-car driver in the country.

In January 1988, Glass was featured in The Achievers on the Turner Broadcasting System cable channel, an hour-long special salute to Black History Month. Later that year, on July 9, at the age of 26, she married a second time, to Charles Michael Opprecht (b. 1965). They would divorce in 1991.

In her professional career, Glass raced in more than 100 events but never achieved her long-held goal of racing in the Indianapolis 500. Through the early 1990s, she did continue to add to a long list of accomplishments, accolades, and awards for driving and personal achievements.

End of the Track

In 1990, Glass purchased her own car, a "March-Buick chassis with its 420hp V6 engine, wings, and slick tires" (Pruett). That October she entered the CART American Racing series Indy Lights at the Nazareth Speedway in Nazareth, Pennsylvania, finishing in seventh place. Later that year, she entered the final Indy Lights race of the year, at the Laguna Seca raceway in California, but failed to qualify there.

William Theodore Ribbs (b. 1956), who in 1991 would become the first African American driver to compete in the Indianapolis 500, met Glass by chance at Laguna Seca:

"I was leaving at the end of the day, and me and my publicist were riding out of the paddock, and I saw her standing out by her tent, stopped the car, got out and introduced myself ... She said she was trying to learn how to drive road courses, and I told her whatever help she needed, to let me know. That was it. The conversation lasted maybe three minutes. She didn’t have much to say ...

She had the guts, times three ...

She was way ahead of her time" (Pruett).

Glass raced a few more times, with her last race coming on April 21, 1991, at Phoenix International Raceway. It ended in a crash. Her car-racing career was over. The next six years of her life would not be the same.

Burglary and Harassment

In 1991, Glass reported three unwanted intruders broke into her home near Lake Forest Park, northeast of Seattle, while she was sleeping. While used to harassment and racial and sexual insults, she never expected to experience it in her home. The wording "Weiss Mach" (evidently a misspelling of "weiss macht," German for "white power") and a large swastika were drawn on the living room wall with her red lipstick taken from her purse. Six months later Glass also alleged that two of the intruders who broke in had raped her, but the prosecutor's office concluded that there was not sufficient evidence to file rape charges.

Throughout the next several years, Glass reported repeated problems with neighbors and local police over a variety of disputes, claiming to have been severely beaten by police officers while being arrested, illegally searched by police, harassed by neighbors, and having her mailbox blown up and her car sabotaged. Neither the charges Glass made nor those made against her resulted in convictions. Glass disappeared from race-car driving and mainstream gigs engaging in activism against injustice and oppression.

Remembering the Driver, Lady Glass

The world unexpectedly lost a brilliant, complex human being when Cheryl Linn Glass died on July 15, 1997, at age 35. Her body was found in Seattle's Lake Union below the Aurora Bridge. No suicide note was ever found but the death was classified as a suicide. Family and friends disputed the finding.

Glass's greatest legacy was being the rising star as the first female African American professional race car driver, stunning both those who were against and for her. For more than 20 years Glass believed that, given the chance to compete against the best drivers at the Indianapolis 500, she could win. She did not get that chance, but her legacy is not forgotten.