George G. Black founded the Black Manufacturing Company in Seattle in 1902. After the maker of "Black Bear" overalls and work clothing outgrew locations in Pioneer Square and Belltown, Black built a new factory at 1130 Rainier Avenue South in 1914, and by 1916 there were 50 men and 265 women employed, with 275 sewing machines in operation and a daily output of 2,460 garmets. The Black family ran the business for nearly 80 years, until 1981, and in 1987 the Black Manufacturing Building received Seattle Landmark status. In this orginal essay, John B. Collins, a former Seattle deputy mayor, writes about the building, the business, and the people, including his aunt, who helped it succeed.

Introduction

This is an historical story of a very successful Seattle company, Black Manufacturing. It is about its people, particularly the founder, George G. Black, and a long-time employee, Catherine Z. Collins, the author's aunt. It is also about their employee-friendly manufacturing building and their well-made and popular clothing.

The story was inspired by Josh Sirlin, who currently [2021] owns Black Manufacturing and the Black Bear brand and is continuing their tradition of manufacturing and selling high-quality clothing. The story relies heavily on articles, photographs, and advertisements in The Seattle Times, a staff report by the city's Landmark Preservation Board recommending a landmark designation for the Black Building, and two contemporary volumes of Seattle and King County history by Clarence Bagley.

Founder George Black

George G. Black, the founder of the Black Manufacturing Company, was born in May 1867, in Kentucky to F. David Black, 52, and Permelia Black, 39. Early in his work career, George was employed in wholesale and dry goods and in the manufacturing of working clothes in Chicago. Later, in Oklahoma, he learned about the retail clothing business. He arrived in Seattle in 1900 and was associated with McDougall and Southwick, a retail apparel store.

In 1902, he organized and began operations as the George G. Black Overall Manufacturing Company in the Smith Building at the corner of 1st Avenue and Jackson Street. The factory operated in a 20-by-30-foot room on an upper floor. It contained a cutting room, six sewing machines, a shipping department, and an office.

Three months after beginning operations, a fire destroyed the Smith Building. Although there was a total loss of materials and manufactured product, there were no personal losses. Black estimated the loss at $7,000, and there was insurance in the amount of $2,000.

George Black served as president, general manager, and sole owner of the business until 1907, when his cousin, J. C. Black joined him and was appointed secretary and treasurer. Also in the summer of 1907, the Times reported, "Mr. George G. Black entertained a party of his friends on Saturday at his summer home on Alki Point. He was assisted in his duties as host by Mrs. Curtis and Miss Curtis, who are spending the summer at the Baker Hotel. Mrs. Baker chaperoned the party, the additional members of which were Miss Millard, Miss Sengfelder, Miss Georgie Smith, Dr. F. A. Black, Mr. Robert Hill and Mr. Joseph Black, who is home on his vacation from Yale. The afternoon was spent cruising on board the yacht Hydia, followed by dancing at Mr. Black's cottage, 'Lonesomehurst'"(Seattle Times, August 7, 1907, p. 8.)

Two years later Black married Sadie Dorsey Brown in Louisville, Kentucky, on March 3, 1909. Her first name on the marriage certificate is "Sadie," but all of the references to her in Seattle refer to her as Sarah.

On February 7, 1927, the Times reported that George Black was in "grave condition" in Swedish Hospital. He had failed to rally after a surgical operation performed three weeks earlier. The death notice the next day in the Times noted: "George G. Black, aged 59 years, beloved husband of Mrs. Sarah Black, father of Nancy Dorsey Black and uncle of Dr. F. A. Black. Remains at the family residence, 3028 Cascadia Ave. Funeral services at the residence, Wednesday at 1 o'clock. Friends invited. Private internment. Bonney-Watson Co. Funeral directors."

In his History of King County, Volume 1, written in 1929, Clarence Bagley wrote, "the notable success attained by the corporation has been largely due to the administrative power and high standard of production set by George G. Black, whose useful, upright life was terminated at the age of sixty years."

A Prominent Architect

After the disastrous fire to their building at 1st and Jackson in 1902, a new plant was soon in operation at 7th Avenue and Battery Street. This building was occupied while the old one was being rebuilt. The factory then moved back to the old location, one whole floor being leased for its accommodation. Before long, one floor was found to be inadequate to the demands of the growing business and another was added, but by 1910 this too was too small, so a move was made to the Security Building on 1st Avenue South near King Street, where a space of 22,500 square feet was obtained.

Within four years this location, too, had been outgrown, and it was decided to build a thoroughly modern plant. A tract of land was secured on Rainier Boulevard, where the permanent factory was constructed during 1914, the equipment was moved in, and on January 1, 1915, the Black Manufacturing Company was established in a home of its own.

When it was built, it was the largest factory for making overalls west of Chicago, and Eastern manufacturers, who visited Seattle for the purpose of inspecting the plant, pronounced it the best garment factory in the world. The building, which is 100 feet by 240 feet and three stories high, contained more window and skylight glass than any other building of the same size in the city. The building, which is still standing, is located at 1130 Rainier Avenue South, and the legal description is Block 4, Rainier Boulevard Addition, Lots 17 through 28, inclusive.

Architect Andrew Willatsen, who designed the building, was already established as an exceptionally talented residential architect after a number of years generating residential projects both in partnership with Barry Byrne and on his own. The Black Manufacturing building marks one of Willatsen's earliest recorded efforts to apply his design and structural knowledge to an industrial building.

Born in 1876, Willatsen (also spelled Willatzen) came to the U.S. with his family in 1902 and settled in Illinois. As an admirer of the work of Frank Lloyd Wright, he moved to Chicago that year to work in Wright's Oak Park studio, where he was given increasing responsibility for projects. Between 1902 and 1905, he executed designs for several Prairie-style houses, a fence for the Larkin Building in Buffalo, New York, and designs for the lobby of the Rookery.

In 1907, he migrated west and worked for the prestigious Northwest firm of Cutter and Malgren in Spokane. As draftsman and later supervising architect for the Rainier Club and Seattle Golf and Country Club, Willatsen became acquainted with Seattle and decided to settle there. He formed a partnership with Byrne, another Frank Lloyd Wright student. Their exceptional residential work for A. S. Kerry and C. H. Clark in the Highlands (1909) promoted the distinctive Prairie style in residential architecture, and led to the establishment of the Prairie School in Puget Sound.

In May 1914, Willatsen was commissioned to design a home on West Highland Drive for J. C. Black, a cousin of George G. Black. Not long after, in 1914, he designed the Black Manufacturing Building. It was one of his earliest departures from the residential style into industrial, warehouse, and commercial buildings, which led to many commissions well into the 1960's. (Readers interested in the design details of the 1130 Rainier Avenue building are invited to consult the excellent Landmark Preservation Board report written by City of Seattle Historic Preservation Officer Karen Gordon.)

The building featured more than 15,000 square feet of windows, and a shed-roof skylight provided healthy daylight for the employees. An overhead fire-prevention sprinkler system was a very early use of such a system. The incentives for the sprinkler system were the safety of the workers and the fact that fire had destroyed the business just 12 years earlier. A 1915 article in Pacific Builder and Engineeer magazine notes, "In fact the character of construction and the system of fire prevention adopted removed every reasonable possibility of fire hazard. So safe is the building that it enjoys the lowest rate of any in the state of Washington."

Grand Opening on Rainier

The building opened on January 2, 1915 with a gala celebration. Reported The Seattle Times:

"More than 3,000 people, mostly young folk, but with a liberal sprinkling of the elders, gladly accepted the invitation extended by the Black Manufacturing Company's employees to formally dedicate the big new manufacturing plant of the company at Rainier Avenue and Norman Street last night, with the result that Pres. George G. Black and Sec. Joseph C. Black were enabled to enjoy the spectacle of 1,500 couples dancing through a program of twenty-two numbers and regale themselves with a bountiful luncheon.

"The entertainment began at 3:30 o'clock, with a program of musical numbers, reinforced with a speech by Councilman Robert B. Hesketh, who represented the city government in the unavoidable absence of Mayor H. C. Gill. The program out of the way, the youngsters began the real fun of the evening in terpsichorean pleasures including the one step, the two step, the hesitation and even some old-time figures like the gavotte and minuet, the music being supplied by an orchestra of ten persons" (Times, January 3, 1915, p. 19).

Hundreds of volunteers, mostly women, served on the Cloak Room, Dance, Decoration, and Reception Committees, and were all individually listed in the Times article.

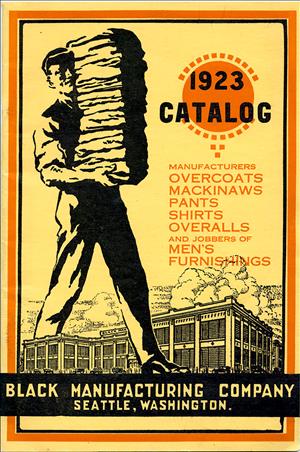

Making Better Workwear

In December 1915, the company added a line of work shirts to its products, in addition to manufacturing overalls, overcoats, mackinaws, pants, and special garments for loggers, fishermen, and other trades. By 1916 there were 50 men and 265 women employed; 275 machines were in operation, producing 205 dozen garments per day, or a total of 52,000 dozen for that year. The plant was so arranged that a total of 584 machines could be installed without building additional room.

The Black Manufacturing Company was one of Seattle's greatest manufacturing institutions from the beginning to near the end of the twentieth century, and the Black Bear brand of clothing did much to demonstrate that in Seattle, goods could be produced just as cheaply and of as good a quality as anywhere else in the U.S.

The manufacturing staff, mostly women, worked hard and carefully, knowing that they would be paid according to the amount of their production. Their health was safeguarded by supervisors and a small medical staff, with a two-bed health care room, and the building construction itself. Warm meals were served at cost, and lectures and special entertainment were provided each week because the Blacks believed that the health, happiness, and prosperity of their employees was of as great importance as were the machines and cloth used in the manufacture of its garments.

As for the production itself, The Seattle Times detailed the process in 1927:

"The cloth, huge bolts of it, is first laid out on tables 218 feet in length. Here the cloth is piled, layer on layer, five dozen deep, making a thick pile. A designer takes his patterns and marks on top of the 218 feet of cloth patterns the cuts to be made, going down the entire length of the table. He first marks the larger cuts and then backtracks and marks the smaller pieces, using every available square inch to avoid waste. Following after the designer comes a battery of electrically driven cutters, machines resembling electric hand drills. These are armed with razor edge knives with a jigsaw up and down motion, going at a terrific speed. A heavy under base acts as the lower guide. The operator simply moves his rapidly reciprocating knife blade along the white lines chalked on the cloth and the goods are cut as desired. In the sewing rooms each machine performs a different operation. These machines are equipped with as many as four needles and sew as many seams in one operation. Operated by electric equipment and controlled by a pressure of the foot, the machines sew and stitch at lightning-like speed.

"One girl may be sewing a pants leg, another sewing in or on pockets at a tremendous rate, another stitches the suspenders, another makes the button holes, and so it goes. Each operator does one distinct job and passes it on to the next. The overall factory is one of the most interesting places about the factory, because it is in this field that the Black company established its reputation. It is now engaged in developing and building water repellent out-of-door wearing apparel, which is rapidly winning its way into the markets of the Northwest and the nation. In the early days when the company was first broadening its production, there was a saying that the condition of business in the Northwest could be gauged by observing the overall market. When the camps and mills, which provided the main industrial activity of the state, were going full blast and were prosperous, the demand for overalls was greater. The demand reflected the condition of the lumber market and was a fairly good guide of the condition of the state financially" (Times, April 24, 1927)

The same Times story, published two months after George Black died, noted a significant company anniversary: "The Black Manufacturing Company, manufacturers of men's clothing, is celebrating its twenty-fifth anniversary. The organization has grown from an obscure workshop to an institution with a payroll of more than $1,000,000 annually. The firm is most widely known from its product, "Black Bear" garment, which were first marketed in Seattle and the Northwest by George G. Black of the organization. A total of 400 persons are employed and daily produce more than 5,000 garments. This clothing is distributed throughout the West and Alaska. The factory is at 1130 Rainier Avenue and has been declared to be a model of its kind."

More Good Press

Another comprehensive story about the company appeared in the Sunday, September 25, 1927, edition of the Times, page 6. Under the headline "Stitching Dollars to Seattle's industrial payroll," the Times wrote:

"Whirling, humming, twirling sewing machines, score on score, manned by women and girls, eating up mile after mile of thread are literally sewing into the industrial life of Seattle millions of dollars annually.

"Here it is that a million dollar payroll is created for Seattle by the process of converting 10,000 yards of cloth daily into 3,260 garments -- each garment representing one payroll dollar. Just a quarter of a century ago, when Seattle was beginning to march rapidly forward as its destiny as one of the leading seaports of the world and metropolis of the Northwest, a man with a vision of the city's greatness, backed by a desire to strike from this section the shackles of manufacturers in other parts of the country, who considered this a trade territory belonging to them exclusively; a man with little capital but with an overwhelming ambition, strengthened by a willingness to make sacrifices and to work twenty-four hours out of each day if necessary, gave to the city and the Northwest its first exclusively wholesale clothing factory.

"Today the Black Manufacturing Company has a payroll approximating $1,000,000 a year. It requires 142,000 square feet of floor space, has an average of 142 persons employed, including 325 operators, 25 salesmen, an office force of 35 and 40 workers in the shipping department. The big plant turns out seven garments a minute, 420 an hour, 3,260 a day, 51,500 a month, a grand total of 988,000 a year. (ed. The numbers don't add (multiply) up.)

"It manufactures overalls, jumpers, denim combination suits, children's play suits, khaki clothing, cotton trousers, woolen trousers, mackinaws for men and boys, overcoats for men, water repellent suits, flannel shirts, cotton shirts and dress shirts. It has extended its trade territory from Seattle and the immediate vicinity to include the states of Washington, California, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, Arizona, and British Columbia, the Hawaiian Islands and Alaska, and now has plans underway to reach the Atlantic seaboard and cover the entire nation with its products."

Innovations and Amenities

Among its innovations, Black was ahead of its time when it came to recycling industrial byproducts. Wrote the Times in 1927:

"The waste from the cutters amounts to around 250 pounds of cloth a day and this goes to the junk dealer, who in turn sells it to the paper mills, so it is not beyond possibility that a person buying a pair of overalls anywhere in the Northwest will find the package wrapped in paper made from the same bolt of cloth from which the overalls were cut, or at least made from waste from the same factory. This is modern industrial methods. There is little, if any, actual waste. That from one industry finds use in another."

The company also was a leader in employee relations, with "its own cafeteria conducted by the employees under a cooperative arrangement. The employees operate this business through their own committee, drawing their help from among their fellow workers, employing only a cook and a dishwasher. It is managed similar to an army mess and the costs are checked up and the employees pay what the meals actually cost. They have no fuel, light, or rent charges to pay. In addition, there is a branch of the public library in the factory, a recreation room, a two-bed hospital, a place where dances and entertainment can be held, a stage, and a safety committee. Then there are girls in the plant who are trained hair dressers and manicurists and in this day of bobbed hair, these girls can be found almost any noon hour or in the late afternoon aiding their fellow workers, clipping, bobbing and curling" (Times, September 25, 1927).

Keeping it in the Family

Following the death of George Black in 1927, Joseph "J. C." Black was elected president of the company, C. H. Black was named vice president, and L. H. Black secretary and treasurer. The three were cousins of George Black.

J. C. Black started with the company while in his teens, leaving for some time, and then returned when George Black died. He and George were second cousins because their grandfathers, Moses Black (1791-1864) and Joseph M. Black Sr. (1791-1850) were brothers, in fact twin brothers.

Lyman H. Black succeeded his brother as president when J. C. died in 1945. Lyman Black served as president until 1958. After leaving Black Manufacturing, he was the treasurer and a director of the Seattle Hardware Co. until retiring in 1964. He was also director of the Pacific National Bank and the Smith Canning Co. He died at age 72 in 1966.

Lyman H. Black Jr. succeeded his father at Black Manufacturing, served as president until 1981 and died at age 90 in 2013. The Black Manufacturing Company was under the same family ownership for nearly 80 years.

George Black and his wife had one child, Nancy Dorsey Black, who died on July 8, 2003, in Seattle, at the age of 87. More than 20 Black family members are buried in the Evergreen Washelli Cemetery in Seattle.

The author's aunt, Catherine Zora Collins, worked at the Black Manufacturing Compnay for 38 years. She was born on January 6, 1894, in Epping Forest, Essex, England. She moved to Seattle sometime between 1910 and 1920, and was naturalized on June 9, 1942.

Catherine began employment at the Black in 1925, where she worked as a secretary, personnel manager, and assistant manager. (When I was growing up in the 1940s, she sent me a wide variety of Black Bear clothing for Christmas presents. The boys' wool knickers, especially the gray ones, were my favorites.)

Catherine retired in 1963 at age 69. She died on January 31, 1983, in Carlsbad, California.

A Seattle Landmark

On September 8, 1987, the Seattle City Council, by a 9-0 vote, designated the Black Manufacturing building as a Seattle Landmark, citing its association with the heritage of the community and its distinctive architectural style. Mayor Charles Royer signed the designation legislation 10 days later.

The company continued its successful operation at 1130 Rainier Avenue South until 1981, when the company was disbanded. The building was vacant from 1981 until 1984, when it was extensively remodeled as corporate headquarters for Darigold LLC, a dairy agricultural marketing cooperative. According to the ciy's Landmark Report: "The rehabilitation of the building was dedicated to recapturing the original design of the building while adapting it to useful modern office and manufacturing space, according to the building's owners. The architectural firm of Ralph Anderson, Koch, and Duarte guided the rehabilitation in conformance with the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Rehabilitation" (Landmark Report).

In 2017, 1130 Rainier Avenue South was vacant and the building was appraised for $9,777,800. With the land, total appraised value for the site was $13,207,800. In 2021, the top floor was occupied by Gray & Osborne, a civil-engineering firm, and the ground floor was still vacant.

A 2017 promotional brochure from Colliers International offering the lease noted: "What was the most up-to-date factory building in America in the 1900's is today recognized as one of the most up-to-date wired buildings of the 21st Century. The 1130 building was renovated in 1999 and 2000 by CMGI to become one of the West Coast's premier, state of the art high-tech buildings for those demanding the best of today's technology. Tens of millions of dollars were invested by CMGI in infrastructure for Activate's live webcasting/streaming business."

George G. Black would have been pleased to know that his building is still "premier" and "state of the art." Black was quite proud to be able to make the claim that his building was the most up-to-date factory building in America, built entirely of Washington-made materials and by Washington workers.

Legacy

The city's Landmark Report summarizes Black's legacy:

"George G. Black, the founder of Black Manufacturing Company, may be viewed in the same historic context as the Nordoffs, founders of the Bon Marché Department Store, the Schwabaker family, founders of the hardware company, and Joshua Green, banker and financier. These men represent a breed of late nineteenth and early twentieth century entrepreneurs whose small first efforts conceived broadly and with vision generated highly successful local and later regional enterprises that had substantial economic impacts and benefits to the Puget Sound area. For its time, "Black Bear" wearing apparel was a remarkably large and prominent industry."