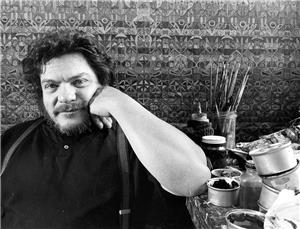

Internationally acclaimed for his densely patterned, symbolic paintings, Alfredo Arreguin was born in 1935 in Morelia, Michoacán. The distinctive painting style he later developed traces back to the vibrant folk arts and dense jungle landscapes of Mexico. He moved to the U.S. in 1956, served in the U.S. Army from 1958-1960, and then studied art at the University of Washington, where he earned a BA in 1967 and a Master of Fine Arts degree in 1969. Arreguin's paintings hang in major Northwest collections as well as national and international venues, including the Smithsonian Museum of American Art and the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., and El Museo Michoacano in Morelia. In 1995 Arreguin received the Ohtli Award, the highest recognition given by the Mexican government to distinguished individuals promoting Mexican culture abroad. In 2013, his hometown of Morelia organized a tribute to him, including an exhibition at the Centro Cultural Clavijero, and then, in 2017, presented him with the keys to the city. His portraits of three Washington State Supreme Court justices hang at the Temple of Justice in Olympia. Arreguin lived in Seattle with his wife, the artist Susan R. Lytle (b. 1952), until his death in 2023.

A Childhood Full of Surprises

Born in Morelia to an unmarried mother, José Alfredo Arreguin Mendoza spent his early years at the home of his maternal grandparents, along with his mother, Maria Mendoza Martínez (1912-1977) and aunts, who moved away one by one as they married. His grandmother, Josefa "Pepita" Martínez would take him to the public market to shop and Alfredo was fascinated by the folk arts on display, the patterned tiles, painted pottery, and intricately embroidered clothing. His grandfather Carlos Mendoza Álvarez bought paints for the boy and encouraged his creativity. When Alfredo was 9, he began studying at the Morelia School of Fine Art. When both his grandparents died within days of each other in 1948, Alfredo was taken to live with his mother, stepfather, and half brother. But after an accident with a gun that injured his half brother while the boys were playing, Alfredo was sent to his aunt in Mexico City. There he got a huge surprise.

All his life Alfredo had been told his father was dead. Now he learned that wasn't true. His father, Félix Arreguin Vélez (1906-2009) was not only alive, but a wealthy man, who did not know his romance with Martínez had left her pregnant. Maria's father had refused to let her marry Félix, who was getting a divorce, insisting he was "not a serious man" (Arreguin interview with author Sheila Farr). Now Alfredo's aunt took the boy to meet that man, who told her, "I don't know if he's my son, but I'm going to help him anyway" (author interview).

He first sent Alfredo to boarding school, then arranged for him to attend the University of Mexico's exclusive prep school, home to murals by Diego Rivera. Alfredo would graduate from there in 1956. But the chaos of Arreguin's upbringing caught up with him. One summer, after he had skipped a lot of school and gotten poor grades, Alfredo was sent to work in the jungles of Guerrero as punishment. Digging irrigation canals in a remote village was hard work, and the environment at the men's camp was rough, across from a brothel, with drinking, fistfights, and sometimes gunfire at night outside his bunkhouse. But the jungle and its native inhabitants enthralled Alfredo. "I saw the most beautiful miracles of nature …" he recalled (author interview). The tangles of dense foliage, the monkeys, exotic birds, insects, and lizards would become predominant motifs in his work.

Chance Meeting with Seattleites

Back in Mexico City, Alfredo was out cruising one day in the 1946 Ford convertible that he'd splurged on, using money his father had set aside for him to start a business. In Chapultepec Park he met a couple from Seattle, traveling with their three daughters. He gave the family a ride to a tourist destination they were trying to find, then entertained the girls that evening, and even traveled with the family to Acapulco to show them around that renowned coastal city. In return, they invited him to Seattle and, later, with the help of Senator Warren Magnuson (1905-1989), managed to get him a permanent visa.

In November 1956, Arreguin arrived in Seattle and began to study English at Edison Tech (now Seattle Central College), where he earned the U.S. high school diploma he'd been erroneously told he would need to enter the university. Then he went on to the University of Washington (UW), where he planned to study architecture. But as a condition of his visa, he became eligible for the draft. "I came to the U.S. and I was in heaven because I was going to the U.," he recalled, "and just as I felt the happiest they drafted me into the army and sent me to Korea" (author interview). Arreguin's initial training took place at Fort Ord, California and then Fort Leonard Woods, Missouri, where he trained to be a typing clerk.

Arreguin's service in Korea was a daunting experience, not because he was on the front lines, but because of the racist treatment he received from his superior officers, who threatened to kill him if he reported their behavior. They called him a "dumb Mexican" and tormented him along with other foreign-born or non-white soldiers (author interview). He remembers two Puerto Rican soldiers who were forced to stay outside all night, got frostbite, and had to have their toes amputated. But Arreguin prefers to dwell on the positive side to his time abroad, which included picnics with native Koreans and traveling to Japan for R&R. The cultural life and artworks he saw in Japan fascinated the aspiring artist, particularly the patterned waves in Hokusai prints, which he later would incorporate in his own paintings.

After his tour of duty, Arreguin returned to Fort Lewis, where he was discharged in December 1960. He returned to Seattle and his architecture studies at the UW. Although he was good at drawing, the technical training of architecture was not for him, so he transitioned to interior design — still trying to please his father and choose a pragmatic line of work.

Meanwhile, Arreguin had begun dating a fellow UW student, Joanne Toft, who became pregnant. After a period of confusion, Arreguin went through with a marriage that her parents had arranged in Carmel, California. Their son, Ivan, was born in Seattle in 1961 and two weeks later a Seattle Times photographer spotted the family at Green Lake on their first outing with the baby. It was an idyllic scene, as Alfredo painted a watercolor and Joanne tended Ivan ("Quiet Spot"). The following year the family moved to a house in Cuernavaca, owned by Alfredo's father. A second child, Kristine, was born there in 1962. Still uncertain of a career path, Arreguin accepted help from his father for a while, considered the possibility of an import business, but eventually decided his best course was to return to the UW to complete his education.

This time, he followed his instincts and enrolled in the School of Art. He found a job as a busboy and rented subsidized housing at Yesler Terrace for his family. But the public housing project was rundown and dangerous, with drug use and crime in the neighborhood. His wife's parents were appalled at the dismal place their daughter and grandchildren were living — all Alfredo could afford. One night when he came home from work, his wife and children had left with her parents, along with most of the family's possessions. Despite his attempts to find them, Arreguin heard nothing for more than ten years, when the children were finally allowed back into his life.

Now on his own, Arreguin got a job bussing tables at the Mexican restaurant Campos, in the University District, and rented a room above the restaurant. There, at Campos, he met another UW student (and later celebrated poet), Tess Gallagher (b. 1943), who became a lifelong friend. She was broke and he used to slip free food to her. However it was, he later recalled, "the most horrible food you can ever imagine. The workers refused to eat there" (author interview).

"Do What You Believe In"

In the art department, the professors who guided Arreguin and helped him the most were Alden Mason (1919-2013), Norman Lundin (b. 1938), Michael Spafford (b. 1935), and Bill Hickson, who became a close friend. The dominant painting style at the time was abstract expressionism and Arreguin struggled to adapt to the art-world influences rippling out from New York. Like the other students, he read the major art magazines and tried out the latest trends. Arreguin earned his Bachelors degree in 1967, and then continued in the Master of Fine Arts program. That's when a prominent Bay Area artist and visiting professor, Elmer Bischoff (1916-1991), took an interest in Arreguin and gave him some advice. Arreguin had been trying out collage, sticking all kinds of stuff on his canvases, and experimenting with anything he saw — flailing around stylistically. "Do what you are good at," Bischoff admonished Arreguin. "Do what you believe in" (author interview). His remarks helped focus Arreguin and gave him permission to tap his own cultural heritage, rather than following trends. He began working with pattern and imagery from his Mexican childhood and incorporating subject matter from the turbulent social events of the period and his own personal life.

With the support of Mason and Spafford, Arreguin received his MFA in 1969 and in a Seattle Times review of the graduate exhibition at the Henry Art Gallery, Arreguin's work was singled out for praise ("New Artists"). Then, in an initial series of post-university drawings called "Signs of the Zodiac," Arreguin further explored the dense patterning that he would develop into his signature style, drawing on his memories of Mexico and Japan, especially the evocative wave-patterns of Hokusai prints. He began entering his work in fairs and competitions, winning awards alongside his former professors. His work was accepted into the 1973 National Drawing Exhibition in Potsdam, New York. Arreguin's drawings, a Seattle Times reviewer noted, "are planted solidly in surrealism and drenched in erotic imagery" ("Three Artists ...").

On the East Coast in the mid-1970s, a decorative style that came to be known as American Pattern Painting was taking hold. Critic David Schaff maintains that Arreguin's work of 1974, defined by his painting "Caleta" — an intricately detailed jungle scene, bordered in a motif of red leaves — "establishes him as the first American painter in this mode," adding that in contrast to purely decorative painting, "Arreguin's work employs pattern to reveal a synthetic, unique context distinct both in inspiration and in continuity" (quoted Flores, Alfredo Arreguin, 50).

Denizen of the Blue Moon

The year 1974 was a pivotal one in Arreguin's personal life as well. He had become a regular at the U. District's storied Blue Moon Tavern, hangout of artists, poets, and assorted misfits and activists, among them the poet and volatile UW professor, Theodore Roethke; Arreguin's pal the poet Tess Gallagher; artist Richard Gilkey; Paul Dorpat, editor of the alternative newspaper the Helix, and HistoryLink.org co-founder Walt Crowley. Gallagher remembers Arreguin, a heavy drinker at the time, as "gigantically unpredictable, maniacally jovial, or swirling like liquid fire around us, scorching us with insights and insults by turn" (Alfredo Arreguin, foreward, xix). The Moon was a place where aesthetics and politics were argued, and fights were fought. Arreguin remembers a night when someone cracked a beer bottle over the head of Gilkey, a famously combative ex-Marine. The artist was rushed to the hospital to be stitched up — and an hour later was back on a barstool, bandaged and ready for more. It was at the Blue Moon in 1974 that Arreguin met the young art student Susan R. Lytle (b. 1952). They fell in love, moved in together, and had a daughter, Lesley, in 1975, before marrying in 1979.

After several years of placing his work in competitions and small gallery shows, Arreguin in 1977 was accepted into the Polly Friedlander Gallery, part of the mainstream gallery scene in Pioneer Square. His exhibition there was featured in a prominent review and photograph in The Seattle Times, which noted that the compositions were "packed, the whole field of vision filled with repetitions of pattern and movement" ("Fantastic Realists..."). But Friedlander (1929-2013) had a reputation for not paying her artists promptly and Arreguin wanted no part of that. He moved on to Kiku Gallery on Capitol Hill, but kept looking for better opportunities. In 1978, the Mexican Museum in San Francisco purchased two paintings and Arreguin exhibited at the Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Art in New York. The following year his work was selected to represent the U.S. at the International Festival of Painting at Cagnes-Sur-Mer, France, where he won the people's choice award. The show traveled to the Musee d'Art Moderne, Paris.

Not shy about self-promotion, Arreguin kept the press apprised of his accomplishments, sometimes striking a contentious tone. A feature story at the time noted that he had been "fighting the art world" ever since he moved here from Mexico. "It's difficult to survive with local hostilities," he told The Times, referring to the racism he'd perceived, "so it's better to get out of town." He continued: "I'm tired of the trend of Hispanic artists painting the Mexican revolution — it's boring to me by now" ("Despite Hostilities ..."). Later in his career, and much mellower, Arreguin would have no problem with honoring heroes of the revolution in his paintings.

Despite his complaints about the local art scene, Arreguin seemed to be right in the middle of it. Mayor Charles Royer (b. 1939) appointed him to the Seattle Arts Commission in 1980, the same year he received a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship. His work was featured in a benefit exhibition for Greenpeace and a show of minority artists at Seattle University. Then he kicked off 1981 as part of a major Henry Art Gallery exhibition titled "Colorful Romances," alongside top artists of the region, including UW professors Francis Celentano (1928-2016), Michael Dailey (1938-2009), and Alden Mason; and then, a few months later, a retrospective at the Bellevue Art Museum.

But Arreguin admits he could be belligerent and hard to deal with in those days of heavy drinking. Through his friendship with Gallagher, Arreguin became friends with her partner (and later husband), Raymond Carver, the celebrated author and recovering alcoholic. In 1983, after Arreguin got in a fight at the Blue Moon and ended up in jail, Carver (1938-1988), helped convince Arreguin to quit drinking. "I realized I couldn't do that anymore: I would lose my wife and career and my health," he recalled — so he quit drinking and smoking, cold turkey: "I thought I was going to die" (Farr phone call). That was in 1984, the same year Arreguin became a U.S. citizen.

When Carver was diagnosed with terminal lung cancer in 1988, he and Gallagher married and Arreguin gave them a painting titled "A Hero's Journey." The canvas showed salmon leaping upstream to spawn. "Ray called them the 'ghost fish' and showed the painting to everyone," Arreguin told The Seattle Times. "The idea was that now the salmon have ceased the struggle and they're free. They may dwell in another dimension, but they're much happier. Ray was really a brave man, carrying on even when he knew what was going to happened to him" ("Epilogue"). Later, "A Hero's Journey," was reproduced on the cover of Carver's final book of poems, A New Path to the Waterfall.

A Brilliant Career

After he quit drinking, Arreguin's career really took off. "It was great, because all that energy in my drinking converted to my work," he recalled (Farr phone call). He had his first one-man show at Foster/White, then-considered the city's premier gallery, and in 1986, Booth Gardner (1936-2013) presented Arreguin with the Governor's Arts Award.

During that period, Arreguin often focused his paintings on a single image, a wild animal or some interpretation of the Virgin Mary, highlighted against and incorporated into a densely patterned ground. In 1988, when he was selected to paint the poster art for the Centennial Celebration of the State of Washington, he chose a similar path. His painting, "Washingtonia," spotlights signature elements of the state in an altar-style three-part format, centered on the peak of Mount Rainier adrift in the clouds. A goldfinch, the state bird, soars over mountains and varied landscapes in a central image flanked by twin panels of blossoming rhododendrons, the state flower. An orange housecat seems to step lightly out of the picture plane and right toward us. "Why the cat?" a friend asked. Arreguin quipped: "Maybe that cat is me" (Alfredo Arreguin's World of Wonders, 43). Arreguin was invited to design the White House Easter egg later that year.

Another figure who has haunted Arreguin's paintings since the 1970s is the now-iconic Mexican artist, Frida Kahlo (1907-1954). Arreguin learned about Kahlo during his youth in Mexico City, when he attended the same prep school where Kahlo had met the famous painter Diego Rivera (1886-1957), at work on a mural for the school. She later married him. Kahlo's moving self-portraits and what Arreguin learned about the hardships of her life, lodged in his mind, long before her images became ubiquitous in Mexico and abroad. They had a personal meaning for Arreguin, because his mother had hoped to be an artist but was not able to pursue that dream. "The portraits had to do with the suffering that Frida endured and her perseverance to become an artist; and her expression which was so strong and raw, really fascinated me. It was sort of like my mother," Arreguin said. "So I use her in my paintings sort of like a ghost that protects the environment ... like a soul that keeps on recurring" (author interview).

By the 1990s, Arreguin's work was gaining in national and international prestige. Even Arreguin's father, skeptical of his wayward son's career path, finally was impressed. Arreguin has his first major show in his native Morelia in 1989, a 20-year retrospective organized by El Museo Regional Michoacano. Then the Smithsonian National Museum of American Art acquired Arreguin's grand, 72-by-144-inch, three-panel painting, "Sueño (Dream: Eve Before Adam)" for the permanent collection. In 1996, he was honored with an exhibition at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C. The Mexican government presented Arreguin with the Ohtli Award in 1997, the highest recognition to individuals contributing to the Mexican community abroad.

The achievements continued to pile up. A scholarship at UW was named in his honor. The Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery invited him to participate in the exhibition "Portraiture Now: Framing Memory," and then retained his painting "The Return to Azatlan" for the permanent collection. The State of Michoacán organized an homage to Arreguin and his work was exhibited at the Centro Cultural Clavijero, Morelia. Later, in 2017, his hometown awarded him the keys to the city. His work has traveled to Spain, Mexico City, and museums across the United States.

Here in Washington, Arreguin was invited to paint portraits of three members of the State Supreme Court: Justice Charles Z. Smith (1927-2016) the first African American to serve on the court; Mary Yu (b. 1957), the first Asian American, Latina and openly gay justice; and Arreguin's friend, Chief Justice Steven Gonzalez (b. 1963). Until his death in 2023, Arreguin and Lytle still lived and worked in the same North Seattle house that had been their residence since 1987, brimming with Mexican folk art and their own paintings and ceramics. The Linda Hodges Gallery in Seattle has represented Arreguin since 2001.