Retailing -- the business of selling merchandise to consumers -- took hold in Washington in the 1850s after the territory's first American-owned store opened in Olympia. As cities and towns grew, the general store gave way to specialty retailers, department stores, and grocery chains. The years following World War II saw massive consumer spending, the advent of suburban shopping malls, and in the early 1980s, the coming of no-frills warehouse club Costco. Retailing underwent a seismic shift after 1995, when Amazon began selling books online from a derelict building in Seattle. In 2020, retail sales in Washington exceeded $178 billion and Amazon was the world's largest retailer, with annual worldwide net sales of more than $386 billion.

Beginnings

The business of retailing was set in motion in Washington on New Year's Day 1850, when the brig Orbit arrived at the new town of Smithfield (now Olympia) carrying gold seekers returning from California. Their greeting party included Michael T. Simmons (1814-1867), who had recently sold his sawmill at Tumwater for $35,000. Wrote Edmond S. Meany in his 1909 History of the State of Washington:

"In the Orbit they returned to Puget Sound, bringing with them Charles Hart Smith, a young man who had come from Calais, Maine, with the gold hunters. Mr. Simmons bought the brig and loaded her with spars for San Francisco. He sent young Smith as supercargo to sell the spars and bring back a cargo of merchandise. In the meantime, Levi L. Smith had died, and his interest in the Smithfield place fell to his partner, Edmund Sylvester, who persuaded Mr. Simmons to start a store in Smithfield and deeded him two lots. A structure of rough boards was reared two stories high and twenty-five by forty feet ground dimensions. In this building the Orbit's cargo was placed, and the first American store was opened for business" (Meany, 226).

It wasn't long before Simmons had competition. In July 1850, Lafayette Balch arrived on the George Emery with a load of goods. "These were unloaded at Olympia, but the town-site owner, Sylvester, was afraid the opposition might injure the Simmons store. He refused favorable terms, and Mr. Balch reloaded the goods, and building a large-frame store at Steilacoom, installed Henry C. Wilson as his clerk and began business in a rival town" (Meany, 227).

Simmons's new venture was said to be profitable, but he had placed too much trust in Charles Hart Smith: "Young Smith was installed as a clerk, manager, and sort of partner. Had he been honest, he might have filled a prominent niche in the commercial history of the Pacific coast. He was sent to San Francisco with $60,000 in cash and credits, and absconded with the whole sum, leaving Mr. Simmons practically bankrupt" (Meany, 226).

Meanwhile, on Alki Point

Meanwhile, about 50 miles up Puget Sound, the Denny Party came ashore at Alki Point on November 13, 1851, and soon Charles C. Terry (1828-1867) had opened a store in a hastily built cabin.

"Having noted what kind of supplies California settlers needed, he came prepared to open a general store and his first goods had travelled up to Puget Sound with him on the Exact. Being meticulous about the care and feeding of money, he kept a little black notebook which is still preserved, neatly listing all the items. He had thoughtfully provided the pioneer settlers with one keg of whiskey, one keg of brandy ... one box of tobacco, one box of raisins, one box of tinware and one box of axes. He quickly put together a cabin in order to display his goods and was in business as 'The New York Cash Store,' with John Low as a partner, in a matter of days. By this time he had acquired from the captain of a trading schooner: more whiskey, some pork, flour, molasses, hard bread, boots, brogan shoes, prints, hickory shirts, window sashes, a glass, grindstones, crosscut saws, files, mustard, pepper-sauce and sugar" (Speidel, 28).

The first dated sale in Terry's ledger took place on November 28, 1851, when he sold two axes to Low for $6. Another early customer was Luther Collins, who had settled on the Duwamish River a few weeks before the Denny Party arrived. "Collins bought six pans, one large and two small tin pails, six pint basins, a coffee pot, two frying pans, two candlesticks, and one dipper. It appears that Collins paid for these goods with 12 salmon" (Warren, 88).

Terry, according to historian Bill Speidel, was a slick businessman. "He bought his merchandise wholesale in San Francisco and sold it at exorbitant prices to the Indians. They didn't have money, so they brought in logs and timbers which he bought cheap and sold dear" (Speidel, 29). Unfortunately for Terry, the location of his store would become a liability. Within a year, most of the Alki settlers had relocated to the eastern shore of Elliott Bay, and in 1852 settler David S. "Doc" Maynard (1808-1873) opened the first general store in Seattle. Maynard, wrote Murray Morgan in Skid Road, "was the town's first capitalist. He hired some Indians to help him build a place down by the Sag, as they called the low land by the water, and within a few days he was selling goods in his new store, the Seattle Exchange, a building eighteen feet long and twenty-six feet wide, with log sides, a shake roof, and over the front part, a low attic that Maynard used as living quarters. The store sold, according to an advertisement Maynard wrote for the paper in Olympia, 'a general assortment of dry goods, groceries, hardware, etc., suitable for the wants of immigrants just arriving'" (Skid Road, 26).

Gold Sparks a Retail Boom

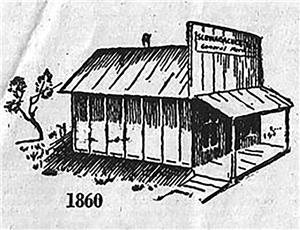

Newcomers began swarming into the region after gold was discovered along the Fraser River in 1858. Wrote historian Cassandra Tate of the gold seekers: "Thousands of miners traveled to the Fraser by way of Victoria on Vancouver Island, turning what had been a provincial outpost in British Columbia into a bustling supply center. Many other miners used Seattle or Bellingham as a jumping-off point. Still others traveled upriver on the Columbia from The Dalles, moving north from there through the Cowlitz, Yakima, Wenatchee, and Okanogan valleys. They all needed food and supplies, which several settlements jostled to supply" ("Gold in the Pacific Northwest"). At The Dalles, at least one store was in place by 1856; 40 settlers sought shelter inside the store during the Cascades Massacre. By 1858, German immigrant Louis Schwabacher had set up a competing store along the Columbia River, and in 1860 the Schwabacher brothers opened a prosperous general store in Walla Walla, not far from new gold fields in southern Idaho.

At Bellingham Bay an estimated 10,000 miners flooded in, hoping the newly built Whatcom Trail would provide easy access to the Fraser River. "Among the local businesses to profit was Thomas G. Richards and Company of Whatcom … the company soon outgrew its wood-framed store and replaced it with a two-story brick building – the first brick structure in Washington Territory" ("Gold in the Pacific Northwest"). One of the hopeful miners to stop at Bellingham was Emory C. Ferguson, who later opened the first general store in Snohomish. According to historian Norman H. Clark, Ferguson was "confident that as the first white man there, he could win a ferry franchise, open a store, file a homestead claim, and make a good living on military traffic while a town grew around him" (quoted in "Gold in the Pacific Northwest"). Ferguson's store eventually failed, but his instincts were sound: By the 1880s, a general store could be found in virtually every town in Washington Territory.

North America's final gold rush began in earnest on July 17, 1897, when the steamship Portland arrived in Seattle carrying 68 miners and two tons of gold lifted from the Klondike River. Thus began a retailing frenzy. "Seattle was advertised throughout the Nation as the outfitting center and point of departure for the North Country. Seventy-four ships were launched between January and July. Old industries expanded and new ones sprang up to meet the demand for machinery, tools, camp equipment, clothing, and foodstuffs" (Washington: A Guide, 219). During the next two years, more than 100,000 people headed to the Klondike gold fields, and Seattle was the starting point for nearly two-thirds of them. "They paid dearly for transportation, subsistence, and supplies. It cost an estimated $1,000 to get to the Yukon with the proper equipment. During the first month of the rush, merchants in Seattle sold more than $325,000 worth of goods to miners headed north" ("Gold in the Pacific Northwest").

Rise of the Department Store

In Washington's larger cities and towns, general stores gradually gave way to specialty stores selling a narrower range of goods. In turn-of-the-century Tacoma, for example, "If you wanted a hat, you went to Reed’s Hats. If you wanted a new dress, you either went to a fabric store and made the dress yourself, or purchased one at a women’s dress shop. If you needed new slacks, you would head to men’s clothier Klopfenstein’s. If you needed a shoe repair or new shoes, you would go to Bone Dry Shoe Store" ("The History of Fashion …").

The number of specialty shops in Seattle increased after the Great Fire of 1889. In 1890 alone, George Bartell Sr. (1868-1956) opened his first drugstore on Jackson Street; Edward (1839-1899) and Josephine Nordhoff (1871-1920) opened the Bon Marche dry-goods store on 1st Avenue at Cedar Street; and Donald E. Frederick (1860-1937) partnered with Nels B. Nelson (1854-1907) and James Meacham to start a used-furniture store near 1st and Pike. A year later, Clinton C. Filson (1850-1919) opened an outdoor-clothing store in Kirkland, relocating the business to Seattle in 1897.

In 1901, Swedish immigrant John Nordstrom (1871-1963) used the proceeds from a disputed land claim in the Klondike gold fields to open a shoe store at 4th and Pike with partner Carl F. Wallin. Over the course of the next century, Bartell Drugs, the Bon Marche, Frederick & Nelson, C. C. Filson, and Nordstrom would become retailing icons in the state's largest city.

Along with specialty retailers, department stores became a staple of urban life during the unfolding industrial age:

"Cities grew in size and population as workers sought jobs in the burgeoning factories, plants, and sweatshops … With employment came wages, and with wages came a desire for a better life, and with that came downtown shopping sprees. To provide room for the merchandise and comfort for the buyer, a new kind of space emerged, the department store … These embodied a commercial e pluribus unum: under one roof, many shops" ("A Brief History Of Shopping").

Among the state's earliest department stores was the opulent and innovative Crescent, which opened in Spokane in 1889 as a small dry goods store. The Crescent grew with Spokane, and within 20 years boasted a staff of more than 300, including several fashion buyers who in 1912 began traveling to Paris. By 1915 the Crescent was doing $3 million a year in sales. It started offering "charger plates," a forerunner of the modern-day credit card, in 1939, and in 1948 the store installed escalators, a rare and expensive novelty.

Department stores were situated in some smaller Washington towns as well, though keeping them stocked could be difficult. In Lynden in 1897, William "Billy" Waples (1875-1962) and Andrew Smith opened a general store which soon became the popular Lynden Department Store. In the early days, "Smith made four trips a week to Whatcom (now Bellingham's Old Town), a nearly 30-mile roundtrip via horse and wagon over muddy dirt or plank roads and across the Nooksack River by ferry. On a typical trip Smith would leave at 4 a.m. and spend the day picking up merchandise at Whatcom wholesale houses, returning at 9 p.m. or later with an average of two tons of merchandise" ("Billy Waples Opens …"). After moving three times into larger locations, Waples built a new store on Lynden's Front Street. It opened in 1914, selling men's and women's clothing, housewares, groceries, dry goods, farm equipment -- and even new cars. Waples "had agencies for a variety of automobiles, including early Apperson 'Jack Rabbit' models" ("Billy Waples Opens …").

Down the Grocery Aisle

In the years before World War I, groceries were usually obtained at specialty shops -- bakeries, butchers, fish mongers, green grocers, and the like. "The standard shopping experience was like a deli. Shoppers asked for items at a counter and [their order] was slowly filled from the back while they interacted with one of the many clerks" ("The Grocery Revolution …"). The first major innovation in the grocery business came around 1915 with the introduction of self-service "cafeteria-style" stores, including the Groceteria chain in Seattle. Instead of requesting items from a clerk, customers carried shopping baskets, selected their own goods, and paid at the front, greatly reducing labor costs for store owners. Founded by Alvin Monson in 1915, Groceteria expanded quickly to include about 30 stores, but after Monson returned from World War I with severe post-traumatic stress disorder, the business faltered. Its last store closed in 1928. "As Groceteria stalled a number of other discount self-service chains entered the Seattle market from outside. First and chief among Groceteria’s rivals was the Washington franchise of Piggly Wiggly … The hole left by Groceteria was filled by a growing list of ever-larger chains. During the Great Depression these coalesced into Safeway and its local rival Tradewell" ("The Grocery Revolution …"). By 1935, Safeway boasted 64 stores in Seattle and dozens more around the state.

The Nordstrom Way

Seattle was booming when Nordstrom and Wallin opened their shoe store in 1901 and it wasn't long before they needed a larger space. They moved to a building on 2nd Avenue between Pike and Union streets, and in 1923 Wallin & Nordstrom opened a second store in the University District. Elmer Nordstrom (1904-1993), John Nordstrom's son, began helping at the 2nd Avenue store at age 12, the start of a legendary career in retailing. Elmer was a "button boy," sewing buttons on women's shoes, and then did stock work. "I also helped with deliveries," he wrote in his memoir, A Winning Team. "In the evenings I would take packages through the alley exit, cross Union and then take another alley between Second and Third to the tiny office of United Parcel Service. Now they're a nationwide delivery service, but at the time they were a small Seattle company started by the Casey family with a couple of trucks and a few motorcycles. They only made deliveries in the city, and we were one of their first accounts" (A Winning Team, 16).

In 1928 Elmer and his brothers Everett (1903-1972) and Lloyd (1910-1976) bought out their father's share of Wallin & Nordstrom, and a year later, shortly before the stock-market crash, they bought out Wallin. With money borrowed from their father, the brothers set about improving and expanding their 2nd Avenue store, leasing an adjacent space to double the square footage and creating a basement area for lower-priced merchandise. They also made the sales floor more comfortable. "In all, we fashioned a store that was considered very modern" (A Winning Team, 27).

Over the next 30 years, Nordstrom would grow into the largest independently owned shoe store in the U.S. Thirty years after that, in 1989, it became the country's largest specialty-store chain. But the Nordstroms had nearly lost it all during the Great Depression. The brothers had made a pact to pay back their father's loan, and with sales plunging, the entire operation was in danger of collapse. "Business got worse and worse, and it looked like we would lose everything," Elmer Nordstrom wrote. "But with liquidation staring us in the face, we had an encouraging upturn and business improved … We put in long hours, watched our overhead carefully, controlled our buying and markdowns, personally attended to every minor detail, and worked closely on all matters. Our main concern was to pay for our store and achieve a solid footing. And we found that, with our combined efforts, we could make ends meet. We got by" (A Winning Team, 35).

After World War II, with their future secure, the brothers turned their attention to expansion. In 1950 they opened a store in Portland, their first out-of-town venture. They then contracted with a string of department stores to lease spaces in which to operate their shoe departments. In a matter of a few years, Nordstrom was selling shoes in Seattle, Portland, Tacoma, Oakland, Honolulu, Albuquerque, Phoenix, Fresno, and Sacramento. It also had made a winning bet on a new phenomenon – the suburban shopping mall.

Coming of the Malls

Retailers, including Nordstrom, prospered in the years immediately following World War II. "Instead of the feared postwar recession, manufacturers struggled to meet consumer demand. After 10 years of the worst depression in history and five years of a wartime economy that paid good wages but directed production to the war effort, American families went on a buying spree. They replaced worn-out appliances and autos, repaired their homes or moved to better ones, and replenished their wardrobes with double-breasted suits and longer dresses now that wartime material shortages were history. They also purchased new products, the prime example being television sets" (Warren, 30). Meanwhile, the nation's car culture had taken hold, contributing to suburban flight and less reliance on downtown retailers. In 1950 the region's first shopping mall, Northgate, opened north of Seattle, with the Bon Marche department store as its anchor tenant.

Not everyone was impressed. In his 1976 book Seattle Past to Present, Roger Sale described Northgate as "a huge shopping center in the middle of what had been, and what in a different way continues to be, nowhere. Northgate had a hundred stores, a skyroof, a mammoth parking lot, and it offered nothing unique, beautiful, tasteful, or offensive. In recent years it has become de rigueur to speak of blights caused by freeways, but the 1-5 freeway in Seattle, when it came, did less damage to its surroundings than did Northgate or Aurora Avenue" (Sale, 190). But if malls failed to please everyone aesthetically, they were hugely popular with shoppers, and Northgate, one of the first suburban shopping centers in the U.S., was on the cutting edge. "Northgate was an instant success … The parking lot was jammed at peak hours for 10 days following opening … The developers used polar bear cubs, a Cadillac giveaway, and a children's play area to attract shoppers. New electric-eye doors in some stores aided shoppers laden with packages" ("Northgate Shopping Mall in Seattle ...").

While Northgate was the brainchild of Bon Marche president Rex Allison, the forward-thinking Nordstrom brothers were quick to get onboard. Recalled Elmer Nordstrom: "When we signed the lease at Northgate in 1949, I drove my father out to view the site of our new store. It was, in those days, quite a drive out in the country … Construction had barely started, and I pointed to a large mud hole, indicating that this was to be our new store. Father was absolutely floored and shook his head slowly. 'I think that you are making a big mistake here,' he said. Actually, we had considered the venture very carefully. Everett had even chartered a light airplane to fly over the area and came back to report that there were large numbers of residential units going up in the immediate area. What seemed like an inordinately big risk to an older man such as my father was a challenging opportunity for us" (A Winning Team, 53).

The next four decades, from 1950 until about 1990, would be glory days for a growing number of shopping malls in Washington. Bellevue Square on Seattle's Eastside and the NorthTown Mall in Spokane were operational by 1955. Next came Tacoma Mall, which opened in 1965, followed in quick succession by Southcenter in Tukwila (1968), the Columbia Center Mall in Kennewick (1969), the Valley Mall near Yakima (1972), Everett Mall (1974), Vancouver Mall (1977), and Alderwood Mall in Lynnwood (1979). Southcenter, conveniently situated at the intersection of 1-5 and 1-405, was the most ambitious of them all. Sprawling over 90 acres, it boasted 1.1 million square feet of retail space and parking for 7,200 automobiles. A crowd estimated at 12,000 turned out for an opening preview and drank 4,800 bottles of celebratory champagne.

The 'Cult' of Costco

By the 1970s, much of the retail sector had shifted to the suburbs. The malls were thriving, while "strip malls" -- clusters of stores sharing a common parking lot -- proliferated along busy arterials such as Aurora Avenue in Seattle and Pacific Highway in Tacoma. "Customarily, they are the locale of a chain-store pharmacy, a bank, a few fast-food restaurants, a nail salon, and a dry cleaner," wrote social historian Stefan Kanfer of strip malls. "And customarily, they are the scar tissue of the American landscape" ("A Brief History Of Shopping"). Meanwhile, supermarkets, introduced in Washington in the 1930s, had grown ever larger through a series of mergers and acquisitions. The grocery business was marked by innovation: Shopping carts were invented in 1937, and 24-hour markets began to multiply in the 1970s. The first supermarket price scanners were not in use until 1974, although bar-code technology had been patented 22 years earlier.

A newcomer to the state's retail mix arrived in 1983 when the first Costco membership warehouse was opened in Seattle. Costco's innovations were numerous: By eliminating most of the frills and costs associated with traditional retailers -- including salespeople, delivery, advertising, billing departments, fancy displays, and grand buildings -- it was able to undercut competitors in dramatic fashion. A yearly membership fee further helped reduce its overhead, "so that items could be sold at an average of 9 percent over cost from the manufacturer" ("Costco Wholesale ..."). Costco's impact was immediate and stunning; it became the first company ever to grow from zero to $3 billion in sales in less than six years.

In 1999 Fortune magazine writer Shelley Branch visited Seattle to interview Costco CEO Jim Sinegal (b. 1936), who founded the company with Jeffrey Brotman (1942-2017). Costco had grown to 289 stores with $24 billion in annual revenue. Under the headline "Inside The Cult Of Costco," Branch wrote: "Unlike predictable discounters, which can numb shoppers with sales and sensible bargains, Costco has figured out that a low price, artfully affixed to high-quality, high-end merchandise, can transcend the pedestrian notion of 'discount.' Played out in Costco's cement-floor aisles, the high/low shopping experience becomes a powerful middle-class elixir" ("Inside The Cult ..."). Fortune reported that one in four American households had a Costco membership, and that Costco had enlarged its red-plastic shopping carts four times since 1984. "Discount merchandising is not for the timid," Sinegal told the magazine. "We'd like it to be known that we are the toughest negotiators in the business. And that we're gonna come after [vendors] for every nickel we can, and we won't let up until we think we've got the price right on the merchandise" ("Inside The Cult ...").

Amazon Upends Retail

As much as Costco altered the retail landscape, its impact paled in comparison to what came next. In 1995, little more than a decade after Costco opened its first store, a 30-year-old Princeton computer-sciences graduate arrived in Seattle to start a company that would sell books on the internet. Jeff Bezos (b. 1964) said he chose Seattle "because it is only one shipping day away from the country's three largest book wholesalers, and because there is a readily available supply of talented software engineers here" (Moody, 207). Six months after Amazon's launch, Fred Moody, a reporter for The Weekly, went to check out Amazon's operations in "a warren of small offices that looked across at the Sears/Starbucks building" (Moody, 206). In the basement, "legions of employees were frantically filling orders. Bezos already was looking for bigger quarters" (Moody, 207).

Bezos had hit on an idea that Moody described as both ingenious and simple. "Bezos built his store by acquiring connections with the electronic inventories of the nation's seven largest book wholesalers, all the formats of which were incompatible with the others. He then wrote translation software that made all the databases readable by his computer system, and wrote more software to make the resulting 'inventory' accessible to his customers ... A customer found the book he or she wanted on Amazon's site and ordered it. Amazon in turn ordered it from the wholesaler who had it in stock, having it shipped overnight to the company's Seattle address, where it would be unpacked, combined with other book from other wholesalers in the same customer's order, repackaged, and shipped that day to wherever the customer wanted" (Moody, 207). Thus was born what by 1999 was the world's biggest online retailer.

Amazon's growth over the ensuing 25 years was staggering. In 2017 Amazon muscled into the grocery business when it purchased the Whole Foods chain, and in January 2021 Amazon, with 75,000 employees in the Seattle area, surpassed Boeing as the state's biggest employer. Reported The New York Times in August 2021, "Amazon has eclipsed Walmart to become the world’s largest retail seller outside China ... a milestone in the shift from brick-and-mortar to online shopping that has changed how people buy everything from Teddy Grahams to teddy bears. Propelled in part by surging demand during the pandemic, people spent more than $610 billion on Amazon over the 12 months ending in June" ("People Now Spend ...").