KHQ radio was one of the earliest stations in Washington, first serving Seattle and then Spokane. Louis A. Wasmer (1892-1967), a Seattle radio enthusiast, launched KHQ in 1922, broadcasting out of his apartment on Capitol Hill. Over the next three years, KHQ became one of the primary radio stations in the young Seattle radio market. In 1925, Wasmer packed up the station and transported it to Spokane, in order to launch a 1,000-watt regional powerhouse. He kept the KHQ call letters and it soon became Spokane's preeminent station. In 1927, KHQ became one of the original affiliates of NBC's Orange Network. In 1935-36, KHQ briefly employed a young radio man named Chet Huntley (1911-1974). In 1952, the station's owners launched a Spokane TV station also using the KHQ call letters. In 1984, KHQ radio changed its call letters to KLSN, to go along with its adult contemporary music format. It would later become a talk-radio station, under the call letters KAQQ and KQNT. The KHQ call letters are now found only in television, where KHQ-TV remains Spokane's NBC TV affiliate. This gives KHQ the distinction of being "the oldest callsign in Washington State still in use," regardless of medium (Harms).

Wasmer's Side Project

In 1922, radio was in its infancy. A number of radio stations had popped up in Seattle and Spokane, but they were barely what we think of today as radio stations. Most were on the air just an hour or two at a time and were often operated by hobbyists and enthusiasts out of homes, garages or shops. Perhaps the best-known radio enthusiast in Seattle was Louis A. Wasmer (1892-1967), who had established himself a decade earlier as the city's top authority on the wireless telegraph, an earlier technology. He had "manufactured most of the wireless equipment used by amateurs" in Seattle ("Who's Who in Seattle Radio"). Yet his wireless obsession remained a hobby. His real job was selling bicycles and motorcycles out of his store, the Excelsior Motorcycle and Bicycle Co. at 301 E Pine Street.

On February 22, 1922, Wasmer announced that this was all about to change. He took out an ad in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer announcing that his motorcycle shop was now selling Westinghouse Radiophones (receivers) for $216 each. "Why not enjoy daily concerts and world news reports in your home?" Wasmer asked ("Radiophone Westinghouse"). Furthermore, he announced that "we are now erecting our own BROADCASTER – to be in operation soon" ("Radiophone Westinghouse"). That broadcaster would soon be known as KHQ Radio.

On February 28, 1922, the U.S. Department of Commerce granted Wasmer a license to broadcast at 833 kHz with the randomly assigned call letters KHQ. The small 100-watt transmitter was located at 419 13th Avenue N (now 419 13th Avenue E), which was Wasmer's apartment. On that day, The Seattle Times described KHQ as Seattle's third radio station, since KFC and KJR had launched just months before ("Three Broadcasters Busy").

After working on the equipment for a few days, Wasmer began broadcasting in early March 1922, with "concerts from noon to 1 p.m. every day and 7 p.m. to 8:30 p.m. every day," as specified in his license application (Harms). This suggests that he was operating his transmitter during his off hours at the shop, which was now named the Excelsior Motorcycle and Radio Company. He also had to share his place on the dial with several other fledgling radio stations, some of which were using transmitters also built by Wasmer.

KHQ's hours were spotty in those early years. In the latter half of 1922, KHQ went on hiatus for months while Wasmer switched out transmitters. On November 1, 1922, The Seattle Times reported that KHQ was back on the air and would now be broadcasting from 7:15 p.m. to 8:15 on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays. In 1923, Wasmer moved KHQ to his new home at 2020 13th Avenue W, which entailed another six weeks of silence. When it came back on the air, KHQ would soon establish itself as one of the city's most prominent stations, mostly broadcasting phonograph records of classical and operatic music.

In early 1925, KHQ's prospects looked especially bright. Wasmer partnered with the Bush & Lane Piano Company, which announced that it would take over operations of KHQ and build its own radio studio inside the store. This would allow KHQ to broadcast live concerts. Yet it was still Wasmer's station; he was the president and engineer, he held the license, and he owned the transmitter. Wasmer named Frank A. "Sparkplug" Buhlert, a familiar Seattle radio voice, to be the station's new director. Wasmer and Buhlert, it seemed, were building a Seattle radio titan.

Opportunity in Spokane

However, they were also harboring dreams of getting out of the crowded Seattle radio market and finding a city ripe for a new, high-powered station. In May 1925, KHQ announced it was "temporarily" discontinuing operations, ostensibly to improve its Bush & Lane studio and boost its power to 1,000 watts ("KHQ To Be Improved"). The shutdown turned out to be permanent. On August 5, 1925, the Times admitted that Seattle had lost KHQ. It had "been silent" for months and was now moving to Spokane ("Around the Radio Dial").

In Spokane, this was already old news. One day earlier, the Spokane Daily Chronicle had splashed a huge banner headline across its front page: "Install Radio Station in Spokane – High Power Equipment Valued at $30,000 Will be Built During the Next Month" ("Install Radio Station in Spokane"). Buhlert, who was making the move as the station's director, explained the decision to the Chronicle. "We had letters from radio men of Spokane asking us to move here," said Buhlert. "After more than a week of investigation here, we are ready to announce the move" ("Install Radio Station in Spokane"). It was partly a matter of geography. Buhlert said they had determined that "Spokane is an ideal field for a station of that size," meaning, 1,000 watts ("Install Radio Station in Spokane"). Several Spokane radio stations were already operating, including the predecessor of today's KXLY, but none with that kind of power.

A legend later sprang up that Wasmer "packed the apparatus for KHQ into the sidecar of his motorcycle and moved to Spokane" (Richardson). This implied that KHQ was small and primitive. However, the Chronicle had reported that the "transmitter itself cost $18,000" -- a small fortune in that era ("Install Radio Station in Spokane"). A sidecar would have been risky, not to mention a tight fit. A subsequent photo of KHQ's broadcasting room, published on the eve of its Spokane debut, showed an entire roomful of transmitting gear ("Station KHQ, Peyton Building"). The sidecar story was repeated throughout the decades and even made its way into Wasmer's obituary more than 40 years later ("Louis Wasmer, Pioneer of Radio"). A more credible version of the story has Wasmer transporting the station in a Model T Ford. No matter how he transported it, Wasmer had nearly four months of work ahead of him: Installing the transmitter, erecting an antenna tower, and equipping a studio.

At first, Wasmer and Buhlert floated the idea of changing the station's call letters. "Although KHQ is our present call, it can be changed later to represent something of significance to Spokane and the Inland Empire," said Buhlert ("Install Radio Station in Spokane"). This did not happen, possibly because the letters KHQ quickly came to be identified so strongly with Spokane.

An Enthusiastic Reception

When everything was finally ready, Spokane gave KHQ the most enthusiastic reception imaginable. On October 25, 1925, The Spokesman-Review devoted an entire special section to the upcoming launch. The cover page said, "KHQ Spokane – Is Calling You" and the back page said, "WELCOME STATION KHQ!" In between were 10 pages of ads and stories, several of which described the station's modern new facilities.

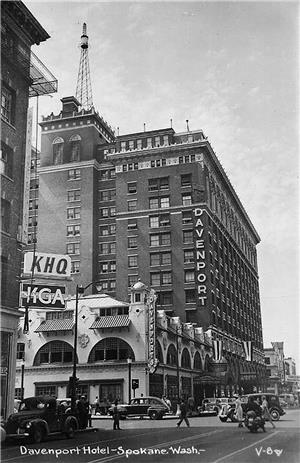

The station – that is, the transmitter -- was in a room on the top floor of the seven-story Peyton Building. The building's roof was crowned by a 90-foot antenna, "mounted on two 70-foot masts" ("KHQ, Spokane's New Radio Station"). The station was equipped with several technological innovations. "KHQ will transmit entirely with battery energy, because generators cause a constant hum and ripple," said the paper. "... Mr. Buhlert says the radio inspector for the four northwest states declared the Spokane plant is the finest in the territory, as to the transmitter, power supply, antennae and the studio" ("KHQ, Spokane's New Radio Station").

The studio itself was across the street from the Peyton Building in the elegant Davenport Hotel, where Wasmer and Buhlert had converted rooms 427 and 428 into an office and remote studio. This separation between the broadcasting room and the studio "prevents interference that often occurs in a one-room broadcasting room," explained Wasmer ("KHQ Tune Range").

"The broadcasting from the station can be picked up at the studio on a Zenith console model, so that at all times the studio director can observe how the program will be going out on the ether," said the paper ("KHQ, Spokane's New Radio Station"). A Davenport postcard photo showed the studio to be furnished with comfortable armchairs and a piano, almost like a parlor. And a parlor apparently required a hostess. "Mrs. Frank Buhlert will be studio hostess," said the paper ("KHQ, Spokane's New Radio Station").

All was ready for the station's Spokane broadcast debut on October 30, 1925, which was no mere switch-flipping formality. It was a four-hour broadcast event, which began with an address by Governor Roland Hartley(1864-1952), who said the enterprise has "put Spokane and the Inland Empire definitely on the aerial map" ("Chronicle to Broadcast Halloween Parade"). This was followed by talks from the president of Gonzaga University, the president of the Spokane Ministerial Association, and the president of the Spokane Chamber of Commerce.

Next came orchestral selections from Spokane's resident orchestra, conducted by Leonardo Brill, and the Davenport's 11-piece jazz band. Various vaudeville and theater groups delivered songs and comedy. Several speakers discussed the Northwest Indian Congress, which was being held in Spokane at the time. All of this programming was being sent out at 500 watts of power -- it would take another few weeks before the station could ramp up to its full 1,000 watts – which was plenty to send the signal far and wide at its 273-meter wavelength, or 1100 kHz.

Buhlert announced that the first 500 listeners who sent telegrams describing their location and the quality of the reception, would receive souvenir "sacks of lead ore from the largest mine in the world," the Bunker Hill & Sullivan Mine ("KHQ's Debut a Big Success"). Telegrams poured in from as far away as Minnesota, California, and Oregon. Local listeners were impressed, too, by the quality of the signal, far clearer and more powerful than what they had been accustomed to. A Spokesman-Review reporter listened in on the console in the Davenport studio. "The reception there was unique in its perfection," he wrote. "Every tremolo of the instruments used and every moderation of the voice was distinctly recorded" ("KHQ's Debut Big Success").

Sports and Poetry on the Radio

The next day, KHQ offered something even more innovative, a radio sports broadcast. This was not exactly a live broadcast. Instead, it was "the play-by-play story of the Haskell-Gonzaga University football game, through the courtesy of the Associated Press and the Spokane Chronicle" ("Football News for Radio Fans"). This probably meant that Buhlert received wire service dispatches on every play and announced them from the studio almost -- but not quite -- as they happened.

Wasmer spent the next few months working on the transmitting apparatus. In February 1926, the signal was boosted to its full 1,000-watt power, and KHQ was given a new spot on the radio dial, 394.5 meters, or 760 kHz, which was about halfway between two powerful signals out of Denver and San Francisco. Buhlert called it a "choice location" which would cut down on interference ("KHQ Assigned New Wavelength"). Wasmer later had to explain to confused radio fans that the lower spot on the dial had no correlation to the station's power.

In this early era, radio stations were still not broadcasting nonstop. In February 1926, KHQ was boasting that it was expanding to 20 hours of entertainment every week, including regular concerts by the Davenport Hotel orchestra and other local classical ensembles, along with poetry readings by Spokane poet Vachel Lindsey and songs by the Cowboy Band of Spokane. A typical KHQ broadcast day in 1926 included two or three hours of music in the afternoon, and two or three hours of music and educational talks in the evening. Occasionally, there were special broadcasts. One of those was a speech by Herbert Hoover (1874-1964), soon to be president, delivered at the Davenport Hotel on August 12, 1926.

To celebrate the station's one year anniversary in Spokane, KHQ took the unusual step of doing a "Dusk to Dawn" event – a continuous broadcast for 10 hours, from 8 p.m. on November 20, 1926, to 6 a.m. the next day. Wasmer called it "one of the most pretentious broadcasts yet made by a radio station" ("Spokane Station Celebrated Today"). "Newspapers in the United States have been notified of the event," said KHQ announcer Cecil P. Underwood, who had replaced Buhlert earlier that year ("Spokane Station Celebrated Today"). Wasmer had secured permission to temporarily boost KHQ's power to 5,000 watts for this special broadcast. After the broadcast, the station received telegrams from all over the continent and beyond. "Reception on the Atlantic seaboard was reported perfect," said the Spokane Daily Chronicle. "People in New York and Honolulu danced to music of the same orchestras" ("Thousands Hear KHQ's Broadcast").

A Powerful Reach

KHQ was now firmly established as one of Spokane's two main stations, and the only one powerful enough to be picked up in the larger West Coast cities. In 1926, Wasmer helped develop a regional network, called the Northwest Triangle, in which KHQ shared programming with KGW in Portland and KFOA in Seattle.

In 1928, KHQ had outgrown its studio in the Davenport Hotel. Wasmer moved the studio and office across the street to the top floor of the seven-story Eilers Building, soon renamed the Standard Stock Exchange Building. Wasmer erected a tower atop the building and strung aerial wires high across Post Street to the Davenport Hotel tower, creating a 175-foot-long aerial. That year, KHQ was assigned the 590 kHz frequency, which it kept until the end.

The programming was still primarily local, because large national networks had yet to be established. That was about to change, and KHQ would be right in the middle of it. In 1927, Wasmer announced that he had signed a contract to become part of the new National Broadcasting Company (NBC). NBC had recently launched two East Coast radio networks, and now it was launching its West Coast network. It was called the NBC Orange Network, and it also included KOMO in Seattle, KGW in Portland, KGO in San Francisco, and KFI in Los Angeles. By mid-1927, KHQ was carrying many of NBC's national programs and KHQ would remain an NBC affiliate to the end.

At this point, KHQ's daily programming schedule was more likely to feature the New York Symphony Orchestra (or later, the NBC Symphony Orchestra) than the Davenport Hotel's orchestra. By 1930, KHQ listeners were tuning into Amos 'n' Andy and other national comedy hits. They were also listening to live World Series broadcasts and other sports broadcasts.

The Golden Age of national network radio had begun, and by 1933, KHQ was carrying NBC staples such as Orphan Annie and Jack Benny. However, local programming was by no means gone – these national programs were still surrounded by local news, local weather reports, farm reports, and local entertainment from KHQ's own studios.

Dubious Distinction

In 1931, some of that local programming earned KHQ the dubious distinction of being the nation's first broadcast station to be sued for libel or slander. The Spokane County sheriff filed a $25,000 damage suit against KHQ over an anti-Prohibition commentary it had aired. The commentary implied that the sheriff was confiscating moonshine equipment and selling it for his own profit. The station's lawyers argued that it was not responsible for the content. An outside party, not employed by the station, had purchased the airtime. The station's lawyers argued that it should not be in the business of censoring commentaries. A court ruled otherwise and awarded the sheriff $1,000. The Washington State Supreme Court ultimately upheld the ruling, which put all broadcasters on notice that they were ultimately responsible for material they aired.

In 1935, KHQ earned a happier distinction by helping launch the career of a young radio man named Chet Huntley (1911-1974). Huntley, a Montana native, was fresh out of the University of Washington with a speech and drama degree. KHQ hired him as an announcer and on December 8, 1935, the station allowed Huntley to put his drama degree to good use. He was featured as one of two performers in a KHQ dramatic sketch titled "Golden Wedding," part of the station's weekly "Leaf From the Tree of Life" program ("Tree of Life Drama"). Huntley was with KHQ only a matter of months. He departed in the first half of 1936 for KGW in Portland, and then on to Los Angeles, where he became a radio news star. In the 1950s, Huntley became one of the most famous TV broadcasters in the world as co-anchor of NBC's nightly Huntley-Brinkley Report.

In 1939, Wasmer moved KGA, another station in his Spokane radio empire, into the old Eilers Building and renamed it the Radio Central Building. This would remain KHQ's home until it moved to a new KHQ radio-TV complex on Spokane's South Hill in 1960. A growing staff of announcers and producers put together a slate of local programming to wrap around the daily NBC network offerings. In 1940, KHQ's regular offerings ranged from the comedy of Charlie McCarthy, the music of Tommy Dorsey, the soap opera of Stella Dallas, the worship service of The Catholic Hour, the wit of The Fred Allen Show, and the country stylings of The Yodeling Cowboy. This is only a fraction of the offerings, since the broadcasting day was often divided into 15-minute segments.

By 1944, Wasmer, had accumulated plenty of power with his broadcast empire and real estate holdings – but then he decided to seek a different kind of power. He announced that he was running for governor of Washington as a Republican. It would be a daunting task just to win the Republican nomination, because he was up against Arthur B. Langlie, the popular current governor. In the end, Langlie "snowed under" Wasmer in the primary by a 4-to-1 margin, Wasmer losing in every county and "swamped even in Spokane, his home" ("Langlie Gets Huge Margin in Primary").

End of an Era

In 1946, the Wasmer era finally came to an end for KHQ. The Federal Communications Commission had enacted rules barring one entity from owning multiple stations in the same city. Wasmer also owned KGA, so he chose to sell KHQ to the Spokane Chronicle Company. The Chronicle, which was part of the city's Cowles Publishing Company newspaper empire, was not shy about touting its new acquisition. "KHQ is the outstanding radio station of the Inland Empire," the Chronicle said in a front-page story. "... From the standpoint of continuous operation under the same ownership, it ranks third in the nation" ("Bright Will Manage Chronicle Radio"). The sale went into effect at midnight on February 28, 1946. Listeners would notice few changes; KHQ remained an NBC affiliate. It was now transmitting at 5,000 watts from what was touted as "the tallest self-supporting tower in the world" at 826 feet high on the Moran Prairie, at the city's southern edge ("Chronicle Seeks Purchase of KHQ").

Nobody realized it at the time, but radio was about to lose its place as America's prime source of home entertainment. A new innovation, television, was arising. In April 1952, KHQ applied for a television station, which would also have the KHQ call letters and would also be an NBC affiliate. The request was approved in July 1952. KHQ-TV put its test pattern on the air in early December and aired its first show on December 20, 1952.

KHQ Radio continued to broadcast its usual slate, but over the next few years, listeners increasingly gravitated to television. The call letters KHQ increasingly meant "channel 6" in Spokane, not 590 on the AM dial. By 1956, the status of radio in general had slipped, as symbolized by the daily newspaper broadcast listings. Television schedules were now at the top of the page, and radio listings were relegated below. Yet KHQ radio listeners continued to tune into favorite shows such as Fibber McGee and The Lone Ranger. They could also tune into a news commentary by Chet Huntley, KHQ alumnus turned national household name. By 1960, however, the comedies and dramas were gone. KHQ radio's schedule was dominated by local news, NBC network news, and music. It would later add Spokane Indians minor league baseball broadcasts, and Spokane Chiefs minor league hockey.

KHQ radio would never regain its preeminence in Spokane's media culture. In 1976, it would switch to an adult contemporary music format, and in 1984, it changed its call letters to KLSN, so that it could call itself Listen Radio. The call letters KHQ vanished from radio, never to return.

On April 5, 1986, the Cowles Publishing Company announced that it had sold KLSN-AM to The Home News Company of New Jersey. In December 1986, the station subsequently changed its call letters to KAQQ, which at least contained a faint echo of KHQ. It changed its call letters one more time in 2002, to KQNT, to go along with a news-talk format featuring Rush Limbaugh. As of 2022, the station called itself Newsradio 590 KQNT and was part of iHeartMedia. It featured syndicated conservative talk hosts Sean Hannity and Glenn Beck.

The only connection with KHQ's 1920s-1930s glory days? The 590 frequency.