The majority of Italian immigrants arrived in the Northwest at the beginning of the twentieth century. Many came to work in the coal mines around Black Diamond; others took on construction jobs or toiled on small family farms. In 1910, Seattle was home to about 3,500 Italians; nearly half settled in neighborhoods southeast of downtown in Rainier Valley and Beacon Hill. The area soon became known as Garlic Gulch, Seattle's version of Little Italy. Services geared toward this newly arrived immigrant group popped up, from grocery stores to barbershops. Our Lady of Mount Virgin Catholic Church tended to the community's spiritual needs. A handful of businesses founded by Italian immigrants or their children, such as Oberto's Sausage Company, Big John's PFI, Isernio Sausages, and Merlino Foods, were everyday brands a century later, although ownership might have changed hands over the years. When Interstate 90 was built in the 1940s and later widened a few decades later, it cut a swath through the heavily commercial district. Many of the original Italian families sold their homes and relocated, small businesses closed, and Garlic Gulch never recovered.

Seattle's Little Italy

The great wave of Italian immigration, which began in the 1880s and lasted until 1920, brought more than 4 million Italians to America. About 75 percent settled in cities on the East Coast, such as New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and Baltimore. By 1910, less than one percent of Italians living in America reached Washington state. That year, Seattle had the state's largest number of Italian settlers – nearly 3,500. About 45 percent of those lived south of downtown in north Rainier Valley and north Beacon Hill in neighborhoods that had been settled earlier by German immigrants. Because of this influx, the area became known as Garlic Gulch.

The exact borders of Garlic Gulch vary, depending on source. A City of Seattle document noted that "the community was centered around the commercial area on Rainier Avenue, between Massachusetts and Atlantic Streets. Residences and institutional buildings, such as Colman School, Mount Virgin Roman Catholic Church, and St. Peter's Catholic Church, were located southward on Rainier Avenue, as well as in the nearby Beacon Hill and Mount Baker neighborhoods" (Seattle Historical Sites). Resident and bakery owner Remo Borracchini, whose family lived in the neighborhood since the early 1920s, placed the borders "east and west of Rainier Avenue, going all the way up to Beacon Hill, as far south as – oh, a little south of McClellan Street" (Tomky).

The early Italians tended to congregate around those from the same village or region in Italy. In this way, they could speak their own regional dialect, eat familiar foods, worship at the same services, and access a network of friends and relatives who could help them find housing or a job. Those from Bari in the Puglia region of Italy settled around other Barese; those from Genoa looked for other Genovese. Garlic Gulch was home to immigrants from both the south of Italy – primarily Naples, Calabria, and Abruzzo – and from the north, including Milan, Turin, and the many small towns of Tuscany.

The Rainier Valley neighborhood was like a small Italian village. "Only 215 families lived there in 1915, but everybody knew everybody else. Rainier Valley was the biggest, but not the only Italian neighborhood. There were about 70 families each in Georgetown and smaller communities in South Park, South Lake Union, Youngstown and First Hill. Families were large and close-knit, as was the community" (Jovina Cooks).

Land was plentiful and relatively cheap. Vegetable gardens were everywhere, and families often made their own wine at home. "Everyone who lived there remembers the aromatic smells of Italian cooking that wafted through the neighborhood, especially on Sunday. The abundance of good food also helped make up for the hungry times some of the immigrants endured in Italy and helped them convince themselves that they had done the right thing by leaving their homeland and coming to this new world. The immigrants' love of and respect for food would lead many of them into new careers and make some of them wealthy" (Jovina Cooks).

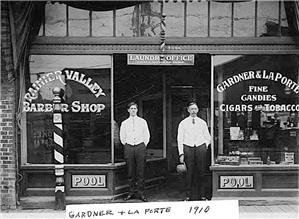

Just about everything a family needed could be found in Garlic Gulch. There were Italian grocery stores – Padine's on 26th Avenue was a favorite – along with a pharmacy, barbershop, meat market, bakery, and macaroni factory. The Vacca brothers sold their fresh produce at their produce stand, Pre's Garden Patch. A saloon called the new Italian Café had "game tables in the back, and farther back, another building housing an Italian-language school, was the main social club of the community" (Scigliano). Atlantic Street Center opened as a settlement house in 1910, helping the newly arrived Italians navigate their new community; it continued to operate as a nonprofit in 2022.

Thriving Businesses, Successful Politicians

Many well-known businesses and brands got their start in Garlic Gulch; some were in business a century later. A few were still being run by family members while others were bought by larger conglomerates. The list includes such iconic brands as Oberto's Sausage Company, Big John's PFI, Borracchini's Bakery, Isernio Sausages, and Merlino Foods. Their stories are examples of hard work, dedication, and a determination to succeed.

John Croce (1924-2015) started selling olive oil out of the trunk of his car before opening his wholesale business, Pacific Food Importers, in 1971. Croce's parents came from San Benedetto Del Tronto on Italy's Adriatic coast in 1906. His family purchased the Atlantic Street Grocery in 1946. By helping his parents run the store, Croce learned the ins and outs of the industry. He parlayed this retail experience into management positions at two chain-owned grocery stores before deciding to go into business for himself. With his bigger-than-life personality and access to specialty food items, Croce was soon a favorite wholesale supplier to restaurants, grocers, manufacturers, and caterers throughout the Pacific Northwest and Alaska. After Croce died in 2015, his son, two daughters, and granddaughter took over the business. In 2020, Big John's PFI, the company's retail shop, relocated from Sodo District to the intersection of S Dearborn Street and Rainier Avenue S – in essence, a return to the old neighborhood.

Frank Isernio grew up in Rainier Valley where his father, Frank Sr., was one of the first produce vendors at Pike Place Market. As a boy, Isernio learned to make sausage at home and found he enjoyed it. The Isernio family, who came from southern Italy, liked their sausage a certain way -- with fennel and a touch of crushed red pepper -- but the product was virtually unknown in the Pacific Northwest. Friends and family encouraged Isernio to turn his hobby into a business. Using traditional family recipes, he set up a sausage factory in a neighbor's basement kitchen and worked night and day to get the business off the ground: "I was a pipefitter at the shipyards, working the night shift from 4 p.m. to midnight. I would go home, sleep for a few hours, get up and make sausage. Then I'd fill my trunk with ice, pack up that day's sausages, and make the rounds of the restaurants to see if they wanted to try my product" ("Frank Isernio Shares ..."). In 2015, Isernio sold the company to Hempler Food Group, a division of a Canadian conglomerate Premium Brands. At the time, Isernio was selling some $14 million worth of sausage annually.

In 1943 when he was 16 years old, Art Oberto (1927-2022) lost his father Constantino (1889-1943), a hard-working Italian immigrant who established a sausage company in 1918 in the International District. To keep the business afloat during World War II, Art rode his bicycle every day after school to the Oberto Sausage Company, filled containers with sausage, salami, and other specialty meats, and then delivered the goods to customers. By 1953, Oberto and his mother had saved enough money to build a small sausage factory at 1715 Rainier Avenue S. When he married Dorothy (1934-2013), the couple built a small house attached to the plant. A marketing genius known for his kooky ideas, Oberto turned a chance phrase -- "Oh Boy! Oberto" – into a household slogan. The business eventually relocated to Kent but retained the original red-brick building on Rainier Avenue as a factory outlet. Oberto's was sold to Premium Brands in 2018; in 2021, the factory outlet closed.

Guido Merlino (1903-1991) left his home town of Taranta Peligna in the Abruzzo region of southern Italy at the age of 17 and moved to Seattle a few years later to join his cousins who ran the Pacific Coast Macaroni Co. The pasta factory, located on Rainier Avenue S, sold its goods under the label of Three Monks. During the height of the depression, Merlino made the decision to sell his shares of Pacific Coast Macaroni and start his own company, Mission Macaroni. It became so successful that it became the Northwest's top macaroni brand, putting several other pasta companies out of business. In 1956, he sold the business to the Golden Grain Macaroni Co. in San Francisco, which was bought out by Quaker Oats in 1986.

Several prominent politicians also grew up in north Rainier Valley. One of the most well-known was Albert D. Rosellini (1910-2011), a two-term Washington governor. "A New Deal Democrat, Rosellini first served the valley's 33rd district in the state senate from 1939 to 1957. His early activism in Garlic Gulch near his home in Mount Baker Park and leadership in the Rainier Business Men's Club supported his successful 40-year career in politics" (Images of America, 90). Rosellini's cousin, Victor (1915-2003), a famous restaurateur, launched several elegant Seattle restaurants that were frequented by the movers and shakers of the era.

The Women of Garlic Gulch

The Italian women of Garlic Gulch often worked side by side with their husbands in the family business, helping to run grocery stores, shops, or restaurants. The interests and well-being of the family were paramount, more important than one's personal goals. Close-knit communities of families and friends provided social outlets and a financial safety net, if times got tough.

Helen Patricelli (1919-2006) reared four sons in Garlic Gulch in addition to working with her husband at Patricelli's Fabulous Drive-in, "a hangout for police officers, who enjoyed free meals and coffee. The Patricellis also owned the nearby Hitching Post tavern and a gas station … Mrs. Patricelli, a feisty woman who once ran a popular Seattle burger joint, often toted around [a] damp cloth, which she'd wind up and snap if she thought someone was getting out of line" (Brunner).

Dorothy Venetti (1934-2013) married Art Oberto in 1954 and helped him grow the Oberto Sausage Company from a small operation in her mother-in-law's basement to a national brand. Beloved by the sausage factory employees for her kindness, her motto was: Life is an adventure.

Garlic Gulch residents Alma (1914-2006) and Gill (1915-1995) Centioli open Gill's Beach Head downtown, where Alma's handmade ravioli was a popular menu item. She also kept the household books and managed the family's real estate investments. In 1950, the couple opened the first 19-cent hamburger joint in Seattle, modeled after the one launched by the McDonald brothers in California. Their children followed in their footsteps: Dorene founded the Pagliacci Pizza Co., Phyllis co-owned Merlino Foods, a restaurant-supply company, and Gerard introduced Krispy Kreme doughnuts to the state.

Spiritual Heart of the Neighborhood

Our Lady of Mount Virgin Catholic Church, which overlooked the Italian neighborhood in Mount Rainier, was the spiritual center of Seattle's Italian community. Mount Virgin was built on the site of a small wooden church erected by Seattle's German Catholic community in the 1890s and named for St. Boniface. As more Italians poured into the area, they shared the church with the Germans but soon the Italians wanted a church that reflected their own heritage and language.

Father Ludovico Caramello (1869-1949), a charismatic and energetic Jesuit priest from a well-to-do family in Turin, Italy, was assigned to the parish. Fr. Caramello helped fundraise for the new church as well as a small parochial school. The church opened in 1915 and served more than 200 Italian families. The school opened three years later. Run by the Dominican sisters of Tacoma, it remained in operation for 60 years. In August 2021, the Seattle Archdiocese announced it would merge Our Lady of Mount Virgin with another parish, but those details were not finalized as of early 2022. The Archdiocese cited dwindling attendance, shortage of priests, and rising costs.

Splitting Apart Garlic Gulch

In 1940, the Italian neighborhood suffered one of several blows when a new highway "sliced through the heart of the Italian community in North Rainier and tunneled through the Mount Baker neighborhood to reach Lake Washington and the first floating bridge. Garlic Gulch never fully recovered (Images of America, 49).

Additional highway expansion caused more problems. During the 1960s, when "the interstate highway system was changing the face of the nation -- wiping out old towns, spawning tacky strips of commerce, and breeding more and more cars and trucks to roar past homes, lower property values and clog city streets" (Reynolds), Washington state decided to widen I-90. The expansion would run straight through the heavily populated streets and the central commercial district of Garlic Gulch. On May 28, 1970, seven Seattle residents went to court to stop the construction, tying up plans for years. After years of studies and hearings, the expansion moved forward in 1979. "Legal and political battles mired the project for more than a decade, keeping the community in limbo. During that time, many residents sold their houses to the state. About 400 homes in Seattle's most ethnically diverse neighborhoods were wiped out" (Ho).

In the early 1980s, an economic recession was in full swing. Crime and gang activities increased, particularly around the areas abutting the I-90 expansion. Mom-and-pop businesses closed, graffiti and trash-filled lots proliferated. At the height of the freeway construction project, PFI owner John Croce told a reporter: "When they put the first floating bridge in, that really screwed up the neighborhood. Then the bridge over Rainier Avenue killed it. This latest thing (the completion of I-90) put the final lid on it" (Scigliano).

The 1980 census counted 6,248 individuals, or 1.3 percent of Seattle's population, who claimed Italian heritage. The largest portion of those – just over 1,000 people – still lived in Garlic Gulch. "One group that has consistently recognized the value of urban property is Rainier Valley's Italian population, which has remained an island of stability in the floods of change sweeping along Rainier Avenue since 1970" (Tewkesbury). During the next few decades, other ethnic groups moved into the area: Vietnamese, Laotian, Chinese, Latinos, and East Africans. By the early 2000s, the streets once fragrant with the smells of Italian cooking were now the home of "pho shops, taco trucks, teriyaki counters, and Ethiopian restaurants, reflecting similar populations as the neighborhood" (Tomky).