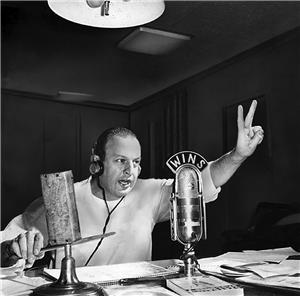

Les Keiter was Seattle-born and raised but made his mark in New York City, where from 1953 until 1963 he was the radio voice of the New York Giants football team, the Knicks basketball club, and occasionally, the Rangers hockey team. The sports director at WINS Radio in Manhattan, he also did pre- and post-game shows for the station's Yankees baseball broadcasts. In 1958, at the insistence of station owner J. Elroy McCaw, Keiter began doing radio re-creations of games played by the San Francisco Giants, who left New York the previous year in Major League Baseball's westward expansion. The re-creations were a huge hit, drawing an average of 300,000 listeners, and were repeated in 1959. After a promised job with the New York Mets fell through in 1962, Keiter left New York for Philadephia, where he gained a rabid following as the voice of Big 5 college basketball and a national reputation with ABC Radio as the blow-by-blow announcer for a string of heavyweight championship fights. Keiter's career inspiration was Leo Lassen, another legendary sportscaster from Seattle.

'A Big, Burly Boy' From Capitol Hill

By all accounts, little Lester Keiter had a one-track mind. He loved sports, but what he really loved was the idea of becoming a big-time radio announcer. Born on April 27, 1919, in Seattle, he grew up on the north end of Capitol Hill where, wrote Jack Sullivan in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, he frequented the Seattle Prep baseball field "with a bunch of Jewish and Irish Catholic kids who couldn't find enough hours in the day to play baseball … Keiter was a big, burly boy and he played shortstop. But he did it like no one else ever has done, before or since. He gave complete Leo Lassen-type play-by-play coverage of the ball game while still playing his position. I don't honestly think that Keiter ever gave one thought to any other career in the world than that of being a sportscaster" ("'Catholic-Jewish Father'").

Even when he was spending a few weeks each summer on Orcas Island, young Les was thinking and dreaming about calling games. He told anyone who would listen that someday he would be calling the action at Yankee Stadium in New York. According to Sports Illustrated, he "spun his first ball game as a 9-year-old around a YMCA campfire" at Camp Orkila, where he spent countless hours playing softball and announcing the games in his head ("On The Radio …"). After attending Seward Elementary School and Broadway High School, he matriculated to the University of Washington, joined the Zeta Beta Tau fraternity, and played on the UW baseball and freshman football teams. Meanwhile, against the wishes of his parents – Jake and Dolly, who disdained football's savagery -- he continued to play sandlot football with the Roanoke Park Rats, a ragtag team of neighborhood kids whose rivals included Gene Cotton's Greeks and Scott's Garfield Stars. "We didn't have the proper equipment or coaching as we might have had in an organized league," Keiter recalled in his autobiography, "but it was football, and a way for me to get around my parents … Then an ironic situation developed: I broke my shoulder playing for the Rats" (Keiter, 7). Thus ended his football career.

With more time on his hands at the UW, Keiter turned his attention to his studies, graduating in 1941. "My interest in sports and broadcasting kept growing all through college, which did not please my parents. They wanted to see me in business or law. They already knew how much I could talk; why waste it on the radio when I could do it for a jury and make a decent living?" (Keiter, 8). Hoping to steer his son into a sales career, Jake Keiter arranged a weekend job for Les in the men's suit department at the Rhodes Department Store, across the street from Jake Keiter's cigar store and restaurant in downtown Seattle. But Les spent too much time huddled in the stock room, listening to college football games on the radio. He was let go. "Slowly, begrudgingly, my parents began to acknowledge the inevitable: their Lester was going to be a sports broadcaster" (Keiter, 9).

Lessons from Leo Lassen

In 1931, "Bald Bill" Klepper, owner of the Seattle Indians baseball club, went looking for an announcer to call a full season of Indians games on KXA Radio. First he tried Bob Hesketh, a respected announcer but an unreliable drunkard. Klepper had little choice but to fire Hesketh after the first month. One or two others were auditioned before an exasperated Klepper "turned to his press agent and asked if he wouldn't please take a crack at it. He did, and a legend was born. Some three decades and 70-odd million words later, Leo Harvey Lassen's name and his shrill, rapid-fire delivery would be familiar in virtually every household on Puget Sound. He was to become the best-known and most respected sports announcer on the West Coast, and just possibly the Pacific Northwest's most outstanding radio personality of all time" (Richardson, 154).

For 12-year-old Les Keiter, listening to Lassen during that summer of '31 brought to life his dreams of becoming an announcer. Listening to Lassen, imitating his delivery, became a favorite pastime, even an obsession. Wrote Jack Sullivan in the P-I. "Leo Lassen, the great Seattle Indian and Seattle Rainier sportscaster, was more than a vogue in those pre-war, pre-inflation days. He was Mr. Baseball. My hero was New York Yankee Joe DiMaggio. Les Keiter's hero? You guessed it. Leo Lassen" ("'Catholic-Jewish Father'"). In The Seattle Times, Emmett Watson claimed "Lassen was ingrained in Keiter's soul. Over baseball board games, Les would announce the tilt with Lassenesque accuracy. When he played left field as a freshman for the Washington Huskies, Keiter would announce the play-by-play in typical Lassen style" ("A Giant Behind The Microphone …").

In short order, Lassen became a master of the baseball re-creation, caling games played too far away to be carried on live radio. His first Indians broadcast was an out-of-town game that he called from the KXA studio in the Bigelow Building at 4th and Pike in downtown Seattle:

"A skilled young Morse operator named 'Hap' Garthright set up his apparatus in KXA's transmitter room. Announcer Earl Thomas sat Leo at a wicker table in the small, ornately carpeted studio adjoining, and after signing the broadcast on the air, kept busy hustling little five-by-seven-inch slips of pink paper to him from the telegrapher. Play-by-play reporting of distant ball games came under Paragraph One of Western Union's Commercial News Department. Only the essential information was transmitted, in a kind of shorthand: S1C for 'Strike one called,' B1 HI for 'Ball one high,' and so on. It was left to the announcer's imagination, intuition and general knowledge of baseball to supply all the rest: the color, the repartee between players and umpires, all that essential trivia about batters tugging at their caps and pitchers glancing at first base before the windup" (Richardson, 157).

Into the Working World

Shortly before Les graduated from college, the Keiter family – Jake, Dolly, Les, and younger brother Buddy (b. 1923) – vacationed at Soap Lake in Eastern Washington. Through a chance meeting at the swimming pool with Spokane businessman Oscar Levitch, Les was offered an interview with Louis Wasmer, owner of two radio stations in Spokane. The interview went well, and "two days later I had a job as a summer relief announcer on KGA Radio in Spokane, starting after my graduation the next month. I was launched. On July 1, 1941, I was officially on-the-air" (Keiter, 12).

He wasn't long for Spokane. Just a few weeks later, J. Elroy McCaw (1911-1969), owner of KELA Radio in Chehalis-Centralia, reached out to the neophyte announcer. "He called from Chehalis and he said, 'I've been listening to you, and I think you're just what we need. Get over here right away'" ("A Giant …"). Eventually, McCaw's radio empire would stretch from Hawaii to New York, and McCaw would be Keiter's benefactor, friend, and fan for the rest of his life. Of their first meeting, Keiter recalled that McCaw "was not an impressive-appearing fellow. He looked like a bank teller," but Keiter was in awe of McCaw's instincts and intellect. "When you were in conversation with him, he'd always be five jumps ahead of you. So many times, he wouldn't say good-bye. He walked out on the conversation. Some thought he was rude. He wasn't. His thought process was in another area" ("Money From Thin Air"). Said Keiter of his boss in Chehalis: "Elroy was direct, he was caring, and he always knew exactly what he wanted. I did all of the things he said I would … and through that autumn of 1941, I began to learn the real ropes of the business" (Keiter, 14).

A Station in the Pacific

Barely five months into Keiter's radio career, his world was turned upside down when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. He enlisted in the Navy in early 1942, went through basic training and was shipped out to Honolulu. Within two months he was promoted to ensign and sent back to the mainland for officer training at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, followed by additional schooling at Fort Schuyler in New York. He then was assigned to Fort Heuneme in California, where he trained with an airfield operations unit called the ACORNS. Recalled Keiter:

"The ACORNS' primary mission was to operate airstrips while the ground was still hot from battle. After training, I was headed to the Russell Islands, just north of Guadalcanal, where the battle was still winding down. It had taken more than six months of training, but by August 1942 I was headed into battle at last. [Later] I was reassigned to a communications outfit. I bounced around some other Pacific islands before landing for over a year on Peleliu, Palau, where I was finally given something to do that I was good at: running the Palau Armed Forces Radio station. I was the station manager, and the station was a full-blown operation with a big staff, right out there in the middle of the war. We played records. We did the news. I did sports, and even had my own show. I had a ball" (Keiter, 17).

Quick Climb to the Top

Keiter returned from the war unscathed. Shortly after his stint at Palau, he was sent back to the mainland for reassignment. He landed in San Francisco on April 12, 1945, the same day President Franklin Roosevelt died in Warm Springs, Georgia. When the war finally ended in September, Keiter returned to his job in Chehalis, but now he was restless for new opportunities and ready to move on. Over the next eight years he would bounce from Chehalis to Modesto, California; to Honolulu, to San Francisco, and in 1953 to New York City and one of the most coveted jobs in sports broadcasting. But first, he got married.

Les had met Lila Jean Hammerslough years earlier. She was the younger sister of one of his fraternity brothers, just a kid, really, and Les hardly paid attention. But when he returned from the war, Lila Jean was all grown up and Les was enthralled. He proposed to her in 1948, on Easter Sunday morning along a dirt road outside of Olympia, and they were married in Seattle on September 9, 1948. Their honeymoon was a whirlwind: Chicago, Cleveland, Niagara Falls, New York, and Washington, D.C. "We ended our honeymoon in Los Angeles, and drove up the coast to our first home, an upstairs apartment in Modesto, California" (Keiter, 24).

Shortly before their wedding, and without consulting Lila, Keiter had accepted a job calling baseball games for an FM station in Modesto. It was the last time he would suffer such a lapse in judgment. About five months after they settled in Modesto, a telegram arrived from J. Elroy McCaw, now in Honolulu: "WONDERFUL OPPORTUNITY FOR YOU HERE, IF INTERESTED" (Keiter, 25). And so, with Lila's blessing, they were off to a new home in Waikiki and a new job for Les as sports director at KPOA Radio. He dove head-first into doing baseball re-creations, "two games a day, seven days a week – major league games in the afternoon, San Francisco Seals games in the evening … Lila was my statistician" (Keiter, 26).

Hawaii felt like home, briefly. In April 1950, McCaw and a business partner purchased KYA Radio in San Francisco, "and, as was now his pattern, McCaw hired Les Keiter to be KYA's sports director" ("KYA Radio's …"). Lila was pregnant when they moved back to the San Francisco Bay Area, and they were still settling into the city when their first child, Ricky, was born on November 10, 1950. A little more than two years later, on November 22, 1952, Lila gave birth to twins Barbara Ruth and Martin Bruce Keiter. A couple of months after that, McCaw called yet again. "Be in New York a week from Monday," he told Les. "You are the new sports director at WINS Radio in Manhattan" ("KYA Radio's …").

The Voice of New York Sports

In New York's frenetic media market, Keiter found his best voice and a wider audience. He did radio broadcasts of the New York Knicks' NBA games from 1955 through 1962, and Giants football games from 1956 to 1959. In 1958 he called the legendary Giants-Baltimore Colts tilt at Yankee Stadium, the first NFL championship game to go into overtime -- a contest remembered by many as the greatest NFL game ever played. Meanwhile, he and Lila settled into a comfortable neighborhood in Port Washington, Long Island, and on February 4, 1958, Lila gave birth to another set of twins, Cindy Marlene and Jody Sue Keiter.

By the time the Giants baseball team relocated to San Francisco in 1958 -- at the same time the Dodgers moved from Brooklyn to Los Angeles -- Keiter was a very busy man with seven mouths to feed. He had signed on with ABC Radio, providing play-by-play for boxing matches, with bombastic ABC Sports Director Howard Cosell as his color commentator. Les also was calling football and basketball games, and doing pregame and postgame shows for WINS' Yankees baseball broadcasts. And then McCaw approached him with another request: He wanted Keiter to do re-creations of San Francisco Giants or Los Angeles Dodgers home games on WINS. "Listen, Elroy, you've got to be out of your mind," Keiter recalled telling his boss. "Sports fans in Manhattan, New Jersey and Westchester are too sophisticated for re-creations" ("Les Keiter, Announcer Who Recreated Giants Games …"). But McCaw was prescient, and in 1959, Keiter's re-creations featuring Willie Mays and the Giants were heard by an average of 300,000 listeners in the New York area. Recalled Richard Goldstein in The New York Times:

"The Giants had gone west along with the Brooklyn Dodgers, but they lingered on Coogan's Bluff and elsewhere in the New York area through Keiter's booming voice and excitable embellishments, aided by his Western Union ticker reports, his taped crowd noise and a drumstick and wooden block alongside his microphone … Keiter monitored telegraph reports bringing the essential play-by-play into the WINS studio and filled in the rest, offering descriptive flourishes based on his best guess as to what was actually happening … Sometimes wearing Bermuda shorts and eating popcorn at the mic, Keiter banged his drumstick against his wooden block to simulate a batter connecting. His engineer activated tapes labeled 'Excited Crowd' or 'Regular Crowd" and on occasion, the sound of booing. One in a while, when the ticker account stopped transmitting or became garbled, Keiter filled in the time by inventing a pitcher-catcher conference on the mound or a batter fouling off pitch after pitch" ("Les Keiter, Announcer Who Recreated Giants Games …").

A Style all his Own

"Gravelly" is a word often used to describe Keiter's voice. According to historian David J. Halberstam, "there was an unmatched energy to his delivery and an exigency to his gravelly sound" ("Remembering A Legend …). Steve Kelley, later a Seattle Times columnist, was an 11-year-old in Philadelphia when Keiter called a 1960 fight between Ingemar Johansson and Kelley's childhood hero Floyd Patterson. As Kelley recalled, "The crackling magic seemed to roll like a wave out of the speaker from the giant radio console and into our living room. The gravelly voice of Les Keiter … maybe the best blow-by-blow boxing announcer in history, was setting the stage for this heavyweight championship fight, sounding as serious as Edward R. Murrow when the bombs were dropping in London" ("Patterson's Life Proved …"). Wrote Emmett Watson, "Les learned much from Leon Lassen, but he went further than Leo did. For one thing, his voice was better, a few octaves lower, but a voice that can reach a rapid-fire crescendo of excitement. Don King, the flamboyant fight promoter, dubbed Les 'Mr. Excitement'" ("A Giant Behind The Microphone …").

Keiter's animated style wasn't for everyone. Critics cited his cliched phrases and his sometimes-overdramatic delivery. "I've never been able to contain my excitement," he explained. "That's the biggest problem I had doing television play-by-play. I couldn't sound like the clones of today. So many of us who were in radio in the old days had to switch to television and it gave us a real problem" ("Colorful Play-by-Play …"). One critic was Marty Glickman, already a well-known broadcaster when Keiter showed up in New York in 1953. "Keiter and Glickman had no love for one another. They were New York rivals who vied for the same gigs and their respective stations for the same rights … [Keiter] was a master of lovable and popular cliches to which Glickman didn't subscribe. In basketball, 'tickling the twine,' a 'ring tail howitzer' and 'in the air, in the bucket.' There was, 'In again, out again, Finnegan' for shots that agonizingly failed after they were halfway down. He covered some bad Knicks teams but made the players sound like warriors and the games like World War III" ("Remembering A Legend …").

King of the Ring

Keiter was a dynamic boxing announcer during one of the sport's golden eras. He had been a boxing fan since age 19, when his father brought him home early from Camp Orkila to attend the middleweight title fight between Freddie Steele and Al Hostak at Seattle's Civic Stadium on Juily 26, 1938. Keiter cried when his hero Steele was flattened by Hostak, but was mesmerized by the power of the sport. "Boxing has threaded its way though my entire career," he wrote in his autobiography. "I broadcast bouts in the Pacific over the Armed Forces Radio Network during the war. In Hawaii in 1949 and 1950, I announced many great fights at the old Honolulu Stadium and Civic Auditorium … I broadcast all those Monday nights at the Eastern Parkway Arena in Brooklyn throughout the 1950s with the likes of Joey Maxim, Hurricane Jackson, and Floyd Patterson. And in 1958, after Patterson finally made his way to the championship, I got the nod, too" (Keiter, 62).

On June 26, 1959, when Patterson met Ingemar Johansson at Yankee Stadium in the first of their three legendary matchups, Keiter realized his childhood dream of calling a sporting event in 'The House That Ruth Built.' It would be the first of his many network radio appearances for ABC. On February 25, 1964, he was ringside with Cosell for Cassius Clay's stunning victory over Sonny Liston in Miami Beach, a broadcast heard by an estimated 75 million Americans. Later, Keiter began doing boxing on network television, starting in 1969 with a Jerry Quarry-Buster Mathis heavyweight title fight. By 1972, he had called a dozen championship fights on radio or television.

After New York, a Cult Following in Philly

In 1960, Keiter took on another assignment, as the first television voice of the American Football League. He did nationally televised games on ABC for the league's inaugural season before giving way in 1961 to Curt Gowdy. A year later, Keiter suffered perhaps his greatest professional setback. Behind the scenes in New York, he had been selected to become the first lead voice of the Mets, a major league expansion team, but at the last minute the club reneged on its promise and hired Lindsey Nelson instead. "It was the beginning of the end for Les in New York" ("Remembering A Legend …"). The following year, after 10 years at WINS, Keiter packed up his family and left New York for Philadelphia and a job as sports director for WFIL Radio and TV. There from 1963 to 1970, he did local sports on television, called 76ers NBA games on radio, and was the beloved voice of Big 5 college basketball.

The Big 5 -- an unofficial league consisting of local schools Penn, Villanova, St. Joe's, LaSalle, and Temple – played games at the Palestra, "an old barn with a basketball floor in the middle, surrounded by benches that held 9,200 loonies" ("Patterson's Life Proved …"). The games could be heated and chaotic, and one night even the mascots – the St. Joe's Hawk and the Villanova Wildcat – brawled during a timeout. From his perch in the rafters, Keiter described the action in his usual excitable manner. When he returned to Philadelphia for Big 5 Hall of Fame induction ceremonies in 1988, he was greeted with open arms. "Les is probably the most colorful play-by-play announcer we ever had," Big 5 executive director Dan Bakers said. "A lot of us who grew up in the '60s loving Big 5 basketball still remember many of Les' favorite phrases. And there's still a lot of interest in him. He practically has a cult following here" ("Colorful Play-by-Play …").

One of the highlights of Keiter's time in Philadelphia was a meeting with fellow University of Washington athlete Brian Sternberg. Keiter was the television announcer for the Penn Relays in April 1963 when Sternberg broke the world record in the pole vault. "I talked with Brian on the field before he competed," Keiter said. "Being from Seattle myself I had a special interest in him. But I said to myself, 'This shy, 19-year-old kid isn't mature enough to break a record. He'll never make it.' The boy certainly fooled me. I've described championship fights, football games and just about every sports event. But I don't think I've ever got a bigger thrill than when that young fellow cleared the bar at 16-5 and I was able to tell my TV viewers that it was a world record" ("Sternberg Thrilled 'Em").

At Home in Paradise

In 1970, with WFIL on the sales block, Les and Lila returned to Hawaii. Back in Honolulu, Les purchased an advertising agency, became sports director at KHON-TV, and called games on KGMB Radio. "On the island, he was an icon, known as the 'General.' He did nightly sports on television, University of Hawaii sports and Islanders AAA baseball ... the man he succeeded doing baseball there was Al Michaels, who left Hawaii for Cincinnati to do the Reds" ("Remembering A Legend …"). During his first two Islanders seasons, Keiter's broadcast partner was Ken Wilson, an aspiring young announcer who, according to Bob Ryan of The Boston Globe, "looks like Rick Barry and sounds like Vin Scully, a disgustingly unfair advantage in life" ("How Ken Wilson …"). By 1977, Wilson had landed a job as Dave Niehaus's broadcast partner with the Seattle Mariners. By then Keiter was 58 and heading toward retirement.

He never did get a chance to call games in his hometown. The SuperSonics, Seattle's first foray into big-league sports, arrived in 1967. More than six months before their first NBA game, team manager Don Richman began sorting through announcers and radio stations for Sonics broadcasts. Bill Schonely, voice of the Seattle Totems, was said to be Richman's first choice, but Schonely was attached to KVI, the home of UW sports. Sonics games would have conflicted with Huskies games, so KVI and Schonely were eliminated. Richman interviewed Keiter, Rod Belcher, George Ray, and Bob Blackburn before hiring Blackburn. Meanwhile, Keiter continued to lobby for jobs in his hometown. On a visit to Seattle in 1970, he told the P-I, "I'm still a Seattleite at heart. I find myself rooting for the Huskies in football, rowing and other sports. I'd like nothing better than to finish my days in a radio or TV job in Seattle" ("Les Keiter Back In Town …").

In 1975, rumors swirled that Keiter would be the first radio voice of the Seattle Seahawks, an NFL expansion team. "I've had some conversations with Les," Seahawks General Manager John Thompson told the P-I. "But the play-by-play announcer will be selected by whichever station gets the radio rights, and that's still quite a ways away" ("'Voice Of Seattle'"). Reported Emmett Watson in January 1976, "Keiter recently has been the sports star of Honolulu's KHON-TV, but he's willing to give up the warm weather to follow the football Seahawks around. Keiter conferred with KIRO (which has the radio rights) early this week" ("The Pulse …"). KIRO eventually hired Pete Gross, who, much like Niehaus and Blackburn, became a beloved broadcaster in the Pacific Northwest.

If Keiter was hurt by being snubbed in his hometown, he didn't show it. Neither the Sonics nor Seahawks are mentioned in his autobiography, and besides, Keiter was relentlessly positive. In 1981, Sports Illustrated's Alexander Wolff traveled to Hawaii for a story. Wrote Wolff:

"It's 5:53 p.m. in Honolulu as Les Keiter pops a Parke Davis throat disc into his mouth and fidgets in his chair in the KSSK Radio newsroom. He eyes his engineer through a plate-glass window. Several yellow sheets are piled on the card table in front of him, face down, next to a drumstick and a hollow wooden block stuffed with pink Kleenex. Keiter, with lineups duly entered in his Scoremaster scorebook, is about to broadcast a Pacific Coast League baseball game being played in Vancouver. From Honolulu. Can it be done? 'Yoooou betcha,' says Keiter, not to that question particularly, but to almost anything. Keiter, 62, is an optimist, and only an optimist could hope to pull off sportscasting's most ancient art – the 'recreation' of the pitches, hits, catches, roars and inviolate rhythms of a ball game – in 1981. No one else is even trying to do it anymore" ("On The Radio …").

Keiter's style and methods hadn't changed much in 40 years, though he had developed a wider range of sound effects with assistance from engineer Leo Pascua. "Pascua has begun to pipe in the buzz of a continuous crowd-noise tape over the air," Wolff observed while sitting in on a re-creation. "Later, on Keiter's cue, he'll augment it with a four-second ooooh; vendors' calls; you average booing; your nastier-than-average booing; staccato applause; a cadenza of cowbells, organ and crowd; 10 seconds of mild clapping, or unfettered rejoicing at a home team's home run" ("On The Radio …").

The Keiters lived out their twilight years near a golf course in Kailua, on the windward side of Oahu. Les retired as sports director at KHON in 1994 but continued as a spokesman for Aloha Stadium for eight more years. In 1991 he returned to Seattle to sign copies of his autobiography Fifty Years Behind the Microphone, and in 2001 he came back for a special occasion. In a ceremony before a Mariners game at Safeco Field, Keiter – along with Blackburn, former Times sports editor Georg N. Meyers, and former Spokane Spokesman-Review sports editor Harry Missildine – was inducted into the Washington Sports Hall of Fame. And in 1997, on Orcas Island, the baseball field at Camp Orkila was renamed Keiter Park for a kid who dared to dream big.

On April 14, 2009, Keiter died at Castle Medical Center near Honolulu. He was 89. KHON reported that he died of natural causes and suffered from dementia. He was survived by Lila, his five children, and numerous grandchildren.