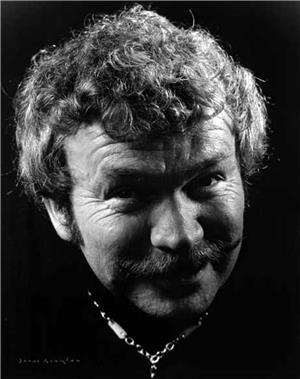

In mid-twentieth century America, AM radio attracted big advertising dollars, and the men (and they were almost all men) behind the microphones were local celebrities. In Seattle, no one was bigger than KVI Radio's Bob Hardwick. He dominated morning drive time, a key time slot, for more than 20 years. Hardwick was called a disk jockey, but he didn't play a lot of records. Instead, he kept the Puget Sound area amused and talking about him with patter, jokes, commentary, and an energetic verbal wackiness that built him a big fan base and sold a lot of ads at high prices. He was a local celebrity, known for wild stunts and adventures, and usually referred to simply by his last name.

A Born Entertainer

Hardwick was born in Seattle in 1931. His father, Lawson Lee Hardwick, was from Martin County, Indiana, a hilly region near the Kentucky border. His mother, born Aileen Mae Breitreit, was a Seattle native. Hardwick grew up in Seattle's Ballard neighborhood near Sunset Hill Park in a stylish Tudor Revival brick house on 33rd Avenue North. His father was an active member of the Masons and served as a "worthy patron," and his mother was a "worthy matron" in the Mason's women's branch, the Order of the Eastern Star. Aileen was active in the PTA, serving as head of its Ballard chapter. Hardwick had two brothers, one older and one younger. Little Robert enjoyed entertaining people from an early age, and fondly remembered his mother's enthusiasm when he danced around the house and pantomimed to Spike Jones records.

Hardwick attended Webster Elementary School and went on to Ballard High School. There, in 1944, he was part of a show put on in the Rhodes department store auditorium by members of the Junior War Savings League, a youth organization selling war bonds. As a senior in 1948 he and another boy were the top-billed performers in a 10-act vaudeville show raising funds for the school. They performed a "burlesque of an adagio." An adagio was a slow partner dance with a lot of lifts and acrobatic moves.

He later said he had started in radio at 15, but his first known on-air job was at a Lewiston, Idaho, station while he was attending Washington State University. Billed as "Snake River Sam," he spoke with a twang and sported a cowboy hat and cowboy boots. In the late 1950s, he also worked at an Indianapolis radio station, quitting right before he was fired for using the word "pregnant" on the air, a word then considered far too graphic for the airwaves. Hardwick would go on to find sly ways to get laughs using double entendre material to avoid censorship.

He came home to Seattle in 1959 to work at radio station KVI, hired by singing cowboy star Gene Autry. Autry had made a string of B movies featuring musical numbers and shoot 'em ups, and invested the proceeds wisely. He owned and operated Golden West Broadcasters, a collection of radio and television stations all over the United States and Canada.

Hardwick would work at KVI until 1980. The 21-year run -- an astonishing length of time in a fickle medium -- was broken only by a four-month interlude, after Autry offered him a spot at his flagship station, KMPC in Los Angeles. KMPC was one of the most successful radio stations in the country. It offered its listeners an MOR format with mainstream music, news, sports, celebrity interviews with local movie stars, and traffic reports that pioneered the use of helicopters. MOR stood for Middle of the Road as opposed to Top 40 stations, which since the 1950s had begun playing rock-n-roll hits for teenagers. After four months, Hardwick returned to Seattle, announcing he didn't like Los Angeles.

An Unconventional 'Disk Jockey'

KVI had a similar MOR format. Hardwick was called a disk jockey, but sometimes he played only two or three records an hour. He kept his audience amused with jokes, patter, and outrageous commentary. Occasionally, he'd turn the mic over to the station secretary, also known in that era as a gal Friday, and let her ad lib while he walked down the hall to the restroom. He also worked with other announcers, including the afternoon man, Buddy Webber. Together they came up with a parody soap opera called Helen Trump: A lot of Woman in a Lot of Places, inspired no doubt by a popular daytime radio soap opera aimed at housewives called The Romance of Helen Trent. That program began with an announcer saying, "Because a woman is 35 or more, romance in life need not be over."

The running joke in the parody was that Helen Trump herself never spoke a word, probably because (with the exception of brief bits from the station's gal Friday) there were no female announcers on staff. Instead, Webber would describe Helen, "sitting on the humble steps of her humble cottage" waiting for her boyfriend, Burien used car dealer Rufus Von Middlesniffer. One of the characters Hardwick played was Upton Peter Dunkel, a professional wrestler. Fans loved it so much they held contests dressed up as the characters.

Aquatic Stuntman

Every big-time radio station had a promotions director whose job it was to organize events, stunts, and gimmicks to enhance the star power of its on-air talent and promote advertisers. Hardwick's stunts were often of an aquatic nature. He dove for treasure in sunken Spanish galleons, traveled from Alaska to Seattle on jet-skis, and, with Seattle private detective Lee Phelps, outfitted a Volkswagen bug with flotation devices and an outboard motor so it could join the parade of vessels going through Seattle's Hiram-Chittenden Locks. He also led a flotilla of 120 small boats to Alaska and went whitewater racing in an Oregon river.

Terrestial stunts included sparring with heavyweight boxer George Foreman, mining for gems in Montana, riding a bucking bronco, trying to ride a Brahma bull, and starting a mock fan club for the Seattle Pilots' amiable underachiever, Ray Oyler, who had the American League's lowest batting average. (Even Oyler's apologetic Topps baseball card said he had hit only three homers in the last three years, "but his brilliant fielding make him invaluable and he's a top notch bunter too.")

Geography was no barrier. Hardwick's activities included climbing Mount Kilimanjaro, and leading fans on three motorcycle tours of Europe. In 1962, Hardwick and afternoon man Buddy Webber were sent on a whirlwind tour around the world in opposite directions, contributing bits of audio travelogue for KVI listeners along the way. The idea was that the two men would arrive back in Seattle simultaneously, just in time to celebrate the opening of Seattle's Century 21 World's Fair. Webber headed west and Hardwick headed east, armed with a two foot plastic replica of the Space Needle. It was jettisoned in London after it broke during a photo shoot in in front of the Prime Minister's residence at 10 Downing Street. Hardwick dined at other towers -- the Eiffel in Paris, the Rotterdam and Cairo towers, and the Atomium Tower in Brussels, built for that city's 1958 World's Fair. By Vienna, Hardwick had lost eight pounds and bought a new belt. Entering Red Communist Bulgaria was a rare tourist stop during the Cold War, and in Hong Kong he befriended a young boy named Fang Tui Wing, who lived with his family aboard a boat. Listeners back in Seattle sent the boy's family $400.

Despite a snowstorm in Sweden and a sand storm in Egypt, Hardwick made it home in time after 9 days, 3 hours, 47 minutes and 2 seconds. Webber was scheduled to join him around the same time for the grand reunion. Webber, who had a reputation for being habitually late, instead woke up his irate boss with a phone call at 3 a.m. Seattle time and confessed he had missed a flight in Beirut and was running late. He arrived almost exactly 24 hours after Hardwick, stripping the stunt of its planned big finale.

In the Firing Line

In August 1963, Hardwick reported received a threatening phone call after an on-air segment of his commentary about vice in Seattle. The next morning, as he was parking his attention-getting 1952 hearse at work before his 6 a.m. shift, two bullets were fired at his car and barely missed him. A story in the national Broadcasting Magazine headlined "Strongarm tactics in Seattle," ran above a photograph that showed him standing by the vehicle pointing to a bullet hole in the driver-side door window. Washington Governor Albert Rosellini called it a shocking effort to silence free expression. Hardwick switched to a less-conspicuous vehicle.

In 1965, Hardwick used his personal tugboat, the Robert E. Lee -- named after himself, although it's possible his name was actually plain old Robert Lee Hardwick -- to tow a floating pen from British Columbia to Seattle's Elliott Bay. The pen contained the world's first captured orca whale. The male orca, then called a killer whale, had been accidentally entangled in fishing nets near Namu, B.C., and was named after the town. Two fishermen who untangled him had sold him for $8,000 to a Seattle man who wanted to display him in a private aquarium on Pier 56. The whale turned out to be too heavy for the small tugboat, and the 65-foot Ivar Foss threw out a line and came to the rescue. It took 19 days to get Namu to Pier 56. Namu died the following year, drowning after being caught in netting during what was thought to be an escape attempt, but not before starring in a movie and launching a global business of displaying trained orcas at theme parks.

Hardwick had a brief fling with television in March of 1965 on Tacoma's KTNT, wearing a suit and interviewing people on a set consisting of two chairs, similar to national network TV shows hosted by Mike Wallace and David Susskind.

Changes in the Air

In the 1970s, AM radio was still highly profitable mainstream entertainment. People who listened to Hardwick on their morning commute discussed his patter and his stunts and adventures with co-workers after they got to work. Hardwick's activities included skydiving, bronc-riding, and driving the Baja 500 and getting stranded in the Mexican desert 100 miles from the finish line for two days. In 1978, Hardwick had the highest ratings in the market and made $30,000 a year, the highest salary of any Seattle radio announcer. That year he was named as the national Radio Personality of the Year by Billboard magazine.

But radio was changing. People increasingly wanted to listen to music on FM stations. By 1978, North American FM stations had a higher listenership than AM stations for the first time. In March 1980, Hardwick walked off his job at KVI in the middle of his morning shift. He was angry with KVI's decision to abandon its MOR format for all-talk, an increasingly popular format for beleaguered AM stations. KAYO, traditionally a country music station where the DJs wore cowboy hats, immediately picked him up at $75,000 a year, more than twice what he'd been making at KVI.

In July 1980, Hardwick swam along the Washington State Ferries route from Bremerton to Seattle, a 10-hour ordeal. It was witnessed up close from boats carrying a swimming coach who helped him navigate swells and currents, reporters, and his sons Christopher Columbus, 11, and Patrick Henry, 9. From the water he told the kids it was important to follow through "no matter how tough it gets." Always emotional, he told reporters afterward "you're so alone … you are alone with yourself … you think of your whole life" (Cartwright). Hardwick raised $4,000 for a sea-life charity.

On July 3, 1981, now 50 years old, he called in sick to KAYO on a Monday morning, and vanished without telling his boss or his family where he was going. KAYO denied his disappearing act was a station publicity stunt. Before leaving town Hardwick had told the Federal Way News that his KAYO morning show hadn't been working and he didn't know why.

His wife Sheila searched their home and found notes on scraps of paper indicating he might be in Billings, Montana. She tried to find him there, leaving her mother to communicate with the press and his employer. After Sheila tracked him down, Hardwick's mother-in-law told KAYO he was all right, but he wasn't ready to come back to work right away. Jack Bankson, his old promotion manager at KVI, said he didn't believe Hardwick's disappearance was a publicity stunt, and described Hardwick as an emotional person, adding that his emotional nature had been a career asset. KAYO station manager Ralph Petti was less supportive, telling the media that the station was the injured party, it was losing advertisers, and it had been paying Hardwick a hefty salary.

By mid-July Hardwick was back in town and ready to speak to Seattle Times reporter Sheila Anne Feeney. He was tanned and upbeat and announced he'd enjoyed his "summer hiatus" in which he had hauled his Harley Davidson motorcycle with his Chevy van for about 5,000 miles, visiting Corpus Christi, El Paso, Amarillo, Salt Lake City, and Denver. He apologized for scaring his family, saying, "I didn't mean to cause so much drama, I was being too cute." Feeney wrote that after slamming "every local station on the air" he added he was still up for a new on-air job, although there was no station in town in he wanted to work for. He said he would really prefer to own a radio station, and wished he had enough money to buy one. He went on to give more interviews in which he attacked the radio business as corrupt, and run by idiots and phonies. He said Seattle was stuck with the lesser of 72 evils -- that being the number of stations in the local radio market.

To Tacoma, and Back to KVI

Hardwick was looking for a job, which, despite his public lambasting of the industry and its managers, he said might be in radio. He also talked about various career options, including opening a gem-specimen store to be known as The Elegant Quarry, starting a fitness program for businessmen, and opening a counseling service for drug and alcohol abusers. In July 1982 he found a home at Tacoma's KTAC which had been a rock station, a format for which Hardwick had no respect. He told an interviewer, "When you're the 'in' station for teenagers you don't have to have any brains or broadcasting knowhow" (Lawrence).

In Tacoma, he pulled yet another aquatic stunt, this time with a parachute. He jumped into a 4-foot-deep swimming pool in the Tacoma parking lot of EmCon Pools at 27th and Yakima, wearing a special diving helmet fitted with a microphone. He carefully pulled the ripcord. Using a bucket of rocks to keep himself from bobbing to the surface, he somehow enveloped himself in the parachute and managed to sing, do commercials, and crack jokes live into the microphone. But by August of that year, he was lured back to KVI, saying he couldn't refuse Mr. Autry, who had personally asked him to return..

In 1983 he was back in the water -- accidentally. He had planned to fly from Nome to Seattle in an $8,000 ultralight aircraft. When he tried to land on a beach for a fuel stop, he tipped over into a lagoon and swam 100 yards to shore, abandoning the aircraft and the trip. By July 1984, however, Hardwick and the station's other big star, Jack Morton, were laid off. The station had never recovered from its format struggles that had begun in 1979 with its switch to all-talk, later followed by golden oldies. The station that had dominated Seattle radio for decades was now losing money.

In 1985 Hardwick was "experimenting with computer info for the masses" (Streidecke, March 10, 1985). He called this mysterious enterprise his "National Digital Radio Service." It was described in the media both as a weekly show about computers, as well as a service that would use radio waves to distribute computer programs in the public domain such as games, filing systems, and even a flight-training simulator. At one point, he had signed up two Seattle stations, but the venture soon failed.

In 1986, he was hired by KIXI-AM, a station that went beyond oldies-but-goodies into deeper nostalgia, with hits from the Big Band era, and lots of Frank Sinatra. He parted from KIXI by phoning the station from California and telling them he wouldn't be in for his morning shift and was considering a career change. Hardwick lasted a year, but the format was still alive at KIXI more than 20 years later.

In 1986 he also began his sixth season as the Evergreen Speedway's track announcer. His wife Sheila was there too, featured driving a Nascar stock car. This yearly gig continued until 1989, when he was replaced as the track announcer and took a job as communications director for the Pacific Institute, a self-help nonprofit run by motivational speaker and high school football coach Lou Tice. He also picked up some work helping several local drug and alcohol rehab centers market their programs.

Hardwick, who appeared as an actor in dinner theatre, also had small roles in two movies filmed in the Seattle area. He was cast as "Dr. Kelley" in Waiting for the Light starring Shirley MacLaine, and as "Senator #1" in Chips the War Dog, both released in 1990.

A Brief Revival at KING

Meanwhile, Seattle radio was still scrambling to keep up with changes in the business. KING-AM had once been a rock station, but was now going with a news-talk formula. It was getting trounced by KIRO. which offered a similar format but had an audience four times bigger. In 1990 Hardwick wrote a letter to KING-AM's program director, congratulating him on a recent uptick in ratings. Soon the two men had lunch and Hardwick had a new job. Hardwick would share the 5-9 a.m. slot with a female broadcaster, Deb Henry. Their off mike relationship was said to be "acidic" ("KING to Shift Gears ..."), and she eventually quit and went to Eastern Washington to raise horses, but Hardwick soldiered on.

In 1991, Hardwick also took a quick free-lance job, providing a voice-over for a television ad run by the Seattle Police Guild. They were protesting budget cuts proposed by Mayor Norm Rice. The ad showed a room full of police officers emptying, while Hardwick said, "When you dial 911 how will you feel when those police officers aren't there?" (Smith).

On April 7, 1992, Hardwick was fired from his job as morning man on KING-AM. A new station manager publicly announced they had fired Hardwick because of poor ratings -- the morning show was rated 14th in the Seattle-Tacoma market. And (presumably without consulting a lawyer) the boss had also volunteered the fact that KING-AM wanted a younger host to draw younger listeners. Older listeners were no longer as valuable to advertisers as the era's plentiful and still relatively youthful baby boomers. Hardwick was replaced with boomer Pat Cashman.

A Shocking Demise

Two months later, on June 3, 1992, people all over the Puget Sound area were shocked when the body of 61-year-old Hardwick was found in a pickup truck just off Highway 2, east of Stevens Pass. He had first tried to kill himself by inhaling the car's exhaust fumes, but when that failed, he shot himself in the head with a .38 caliber automatic pistol. He left several notes. One of them asked police to notify his wife Sheila and to "be gentle" with her (Guillen and Boss). He had also written that he was getting older and unemployable and didn't want Sheila to have to support him.

His friend Jack Morton, then working as a weekend maritime reporter on KIRO, said, "He'd always mention we were getting older. The business is getting younger. You have to scratch to hang on" ("Radio Personality Commits ...").

His widow and his estate -- representing his 7-year-old son Robert Lee Hardwick and three adult children by a previous wife -- sons Christopher and Patrick and daughter Linda -- sued for wrongful termination and wrongful death. The suit alleged his 1992 firing was based on age discrimination and had driven him to suicide. Sheila Hardwick told the media that two weeks before KING fired her husband, program director Steve Wexler had "put his hands on Robert's shoulder and announced to the staff that "this is the voice around which we will build our station. The changes are over, and this is the team we're going with." The lawsuit said, "He felt a loss of dignity, a total loss of purpose and an inability to work in a field that he loved, and he felt he had no way to take care of his family" (Taylor).

The lawyer representing Sheila Hardwick pointed out that the law against firing older people in order to replace them with younger people protected anyone older than 50. Hardwick was 61, and the station manager had publicly announced he had fired Hardwick because he was too old, and replaced him with a younger man.

The founder of King Broadcasting, Dorothy Stimson Bullitt, had sold her television station and cable business before her death. Her two daughters, who had not shared their mother's interest in broadcasting, were in the middle of selling the AM station to KIRO Inc. and donating KING-FM, a classical music station, to a nonprofit corporation to help fund other arts organizations. How the matter with the Hardwicks was settled does not appear to have been made public.