The now-abandoned mining town of Franklin on the Green River in Southeast King County just east of Black Diamond grew up in the 1880s around mines extracting coal from the many coal seams in the Green River Gorge. The first wave of mining had largely ended by the 1920s, but after World War II mining began at two seams across the Green River from the townsite and continued into the early 1970s. After the mines closed, coal in one spontaneously combusted and the smoldering coal led to creation of a hot spring at the mine's mouth on the river that lasted for a number of years. Bill Kombol of the Palmer Coking Coal Company contributed this People's History of the last mines in Franklin and the now-lost hot spring.

Early Mining at Franklin

The final chapter of coal mining at Franklin began in the early 1940s, six decades after the town was established. Mining was first made possible following construction of the Columbia & Puget Sound Railroad to Black Diamond. Extending the tracks the final two miles to Franklin in 1885 opened up another source of revenue to ensure the railroad's success. For without a railroad there could be no coal mines, but without coal mines there could be no railroad.

During its heyday in the late 1890s and early 1900s, Franklin boasted more than 1,000 residents. The town's fortunes were linked to the 50-million-year-old coal seams exposed by the deep gorge carved by the Green River.

There are 18 coal seams in the Franklin series, the most famous being the McKay (No. 14). The second most heavily mined vein was the Gem seam (No. 17). A small segment of the Harris seam (No. 18) was opened in conjunction with the Gem. The Fulton (No. 12) was the thickest at more than 36 feet in width. The Franklin No. 9 was barely mined and the No. 11 seam only slightly. The Franklin No. 10 was the last to be extensively mined, but didn't have a colloquial name like some of the others.

Development of the Franklin coal mines began in 1884, after the Oregon Improvement Company (OIC) assumed control of the land following assurances that its rail line to Black Diamond would also extend to Franklin. The first trainload of coal was shipped from Black Diamond in April 1885. Two railcars filled with 96 tons of coal left Franklin July 21, 1885, reaching San Francisco in early August. At the time Washington was still a territory and wouldn't achieve statehood until November 11, 1889.

Troubles Under OIC

Throughout its early history Franklin was beset with troubles. Those years saw labor strife and mine tragedies in quick succession. In 1891, the Oregon Improvement Company attempted to lower wages by importing Black strikebreakers from the Midwest. The white miners who lived in Franklin refused to budge. After violence broke out the National Guard was dispatched to restore order. The strike was broken, and white miners slowly returned to work, taking their place alongside Black miners. The company won the battle, but at a cost.

Three years later, Franklin witnessed the second-worst underground coal mine disaster in Washington history when 37 men perished on August 24, 1894. It was a gruesome affair due to a series of errors, including a worker who stopped the mine's fans at a critical moment. Though ventilation was restored 15 minutes later, the victims were trapped 700 feet underground on the 6th level north. They died, overcome by smoke inhalation. Many miners were discovered with their faces in the mud trying to escape the noxious fumes. The body of Evan John, the 19-year-old son of John E. John, was found gripping his father's arm as a safety lamp lay nearby. The tragedy produced 14 widows and orphaned 38 children. A subsequent investigation suggested the fire may have been deliberately set, though no evidence was produced to support the claim.

OIC entered receivership in 1896, blaming its financial difficulties on labor troubles, mine fires, and the loss of a contract to supply coal to the Oregon Railway & Navigation Company. It was the company's second bankruptcy in 16 years.

Pacific Coast Expands Production

The following year, the newly formed Pacific Coast Company (Pacific) absorbed the insolvent OIC, taking control of its operations. Pacific was a conglomerate owning coal mines, railroads, steamships, and later briquet and cement plants. Pacific Coast Coal Company, its mining division, would in time own mines in Newcastle, Issaquah, Black Diamond, Franklin, Carbonado, and Burnett. Franklin finally had a solid financial footing and better mine management.

Investments in new mines and machinery led to an expansion of Franklin's operations. By the late 1890s and early 1900s, coal production was averaging nearly 200,000 tons per year. Coal output, however, slumped in 1908 and employment fell. This was the beginning of a long decline, save for a brief period when a new opening called the Cannon Mine was developed.

The Cannon Mine was planned to exploit reserves east of the Green River, which required construction of a bridge across the river, built in 1913. Though heavily capitalized, the Cannon Mine never fulfilled expectations and the town's output rapidly dwindled. By 1922, coal mining in Franklin was defunct and the settlement mostly deserted. The Cannon Mine bridge was eventually repurposed to carry spring water to Black Diamond -- its primary source of water -- and still stands today.

In January 1941, Pacific sank a new opening on the McKay seam parallel to an earlier underground operation. Franklin No. 7 (named for the section, not the seam) had been successfully operated from 1893 to 1907, producing significant tonnage. A Columbia & Puget Sound rail line, called the Bruce spur, was extended around Mud Lake to haul the coal to market.

Both the new and old mines were located south of the Green River Gorge Road. The large, remnant coal slag pile can still be seen behind a gate, 900 feet east of the Department of Fisheries boat launch access to Lake No. 12, named for Section 12.

Curiously, Pacific Coast Coal named its second opening in Section 7 the Black Diamond Mine, though the area was long associated with Franklin. Mining was started by the Strain Coal Company under lease from Pacific. In 1942, Pacific took over operations. Production was hobbled, though, by inexperienced employees, as many seasoned coal miners joined the armed forces during World War II. Mining under Pacific's management continued until August 1, 1946. Surface mining on the Fulton seam produced additional coal, but that effort ended several months earlier in March 1946, after demand for coal declined precipitously at the war's end.

A New Post-World War II Beginning

It was then that a new company, sporting the same PCC initials, took over mining in Franklin. The firm, Palmer Coking Coal, was founded in Durham in 1933. Palmer absorbed its sister company, Morris Brothers Coal Mining Company, in 1937, and that same year began extracting coal from mines in the Danville and Ravensdale areas.

In 1947, Pacific leased its Franklin coal reserves to Palmer. Six years later in 1953, the parent firm, Pacific Coast Company, which owned both Pacific Coast Coal and Pacific Coast Railroad, signed a four-year real estate contract with a Palmer affiliate to sell its King County coal properties, assets, and business interests, including the Franklin townsite. The overall land component involved more than 8,000 acres and concluded in 1957, after 2,000 of the acres were sold to Weyerhaeuser Timber.

Palmer's years in Franklin were primarily focused on the No. 12 (Fulton) and No. 10 seams, with 675,000 tons of clean coal removed from an assortment of surface and underground operations. Franklin No. 12, originally known as the Fulton seam, was first mined in 1887, after a large, well-equipped slope was sunk. The coal was also worked in the early days from a water-level tunnel just above the river. Franklin No. 10 was briefly mined in the first few years, but only in earnest after World War II. Those two seams dominated mining from 1946 until 1971, when the last underground coal mine in Franklin was blasted shut.

Mining Moves East Across the River

Though the old company town had vanished, Franklin's coal production was not yet complete. Before 1950, almost all of Franklin's coal was mined on the west side of the Green River, where rail facilities and the townsite were located. The sole exception was the Cannon Mine, whose commercial failure marked an end to mining in Franklin for nearly two decades.

Extension of the Franklin No. 12 mine east across the Green River didn't advance until after a timber-span bridge was built, most likely in 1949. A November 1949 map was the first to show the bridge and mine opening east of the river. The Franklin No. 12 mine portal was located one-half mile downstream from the Green River Gorge bridge. A gangway more than 3,500 feet long was eventually driven southeasterly, under the Enumclaw-Franklin Road, and then due south. Mining from this opening continued for the next 10 years.

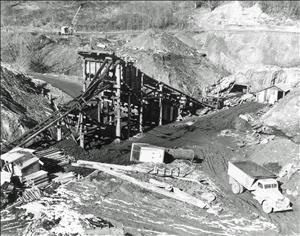

The bridge accessing the Franklin No. 12 portal was fitted with iron rails, secured to wooden ties, and suspended about 20 feet above the river. From the west, or Franklin, side of the Green River, a cable hoist pulled loaded coal cars from the mouth of the mine, across the river, then, on the west side, around a corner and up a hill to where the tipple and hoist facilities were located.

The tipple was a large, wood-frame structure, triangular in design, where the rail track climbed to achieve height. A hoist was like a giant fishing reel with a thick, one-inch steel cable spinning around a pulley wheel atop the tipple. As each four-ton rail car reached the top of the tipple, a mechanical lever tripped the car's tailgate, allowing coal to fall into a load-out bunker for haulage by dump trucks to Palmer's Mine 11 preparation plant in Black Diamond.

While coal from the No. 12 bed was being mined east of the Green River, the same seam was exploited by surface and underground methods farther north and above the old Franklin townsite. In one photo from the early 1950s, both mining methods are being simultaneously undertaken near where Randolph Creek crossed over the Fulton No. 12 coal seam.

Surface mining of the Fulton ended in the mid-1950s. Randolph Creek would henceforth flow through abandoned underground workings of the No. 12 seam directly to the Green River. The waterfall where the creek historically cascaded overland dried up for all but the heaviest rains. A remnant water flow can sometimes be seen during intense winter storms above a guard rail on the west side of the Green River Gorge Road, about one-third of a mile from the single-lane bridge.

Before the Howard Hanson Dam was completed in 1962, the Green River could rise to extreme levels, causing downstream flooding, particularly in the Kent Valley. One year during the 1950s, the Franklin No. 12 timber-span bridge washed out and was rebuilt over the Christmas holidays.

Mining on the No. 12 seam was completed in early 1959, and for a brief time thereafter the mine tunnel was repurposed by a local civil-defense group as a fallout shelter when fears of nuclear war were mounting. Several news articles with photos highlighted this unique attempt to protect civilian populations, but the effort was short-lived. The mine flooded in November 1959 and was subsequently abandoned.

Franklin No. 10's Beginning and End

In 1964, Palmer opened its Franklin No. 10 mine on the east side of the river. It was a near duplicate of its downstream predecessor, Franklin No. 12. The new portal was reached by a similar log bridge outfitted with rails and wooden ties, with comparable load-out facilities, including a tipple and hoist on the west side of the river. Al Ballestrasse of Enumclaw hauled in four 110-foot timbers placed with a logging skyline. Bill Sharp, a mine carpenter from Issaquah, built the bridge decking.

Franklin No. 10 produced more than 66,000 tons of coal during seven years of operation, but its days were numbered due to tightening federal mining regulations coupled with a desire by park advocates to preserve the Green River Gorge.

In 1968, Washington State Parks announced ambitious plans to acquire and conserve thousands of acres along the wild and scenic gorge, a 12-mile reach of the Green River stretching from Kanaskat to Kummer. This part of the gorge is dominated by steep canyon walls and is mostly inaccessible, except for select areas with favorable topography. The old town of Franklin, with its rich mining heritage, was chief among properties targeted for preservation. Palmer's ownership in and around Franklin was a key component for making that conservation dream come true.

On March 27, 1971, the last underground coal mine in Franklin was blasted shut. The event was filmed by an NBC television crew for national broadcast on the network's "First Tuesday" news show, which aired from 1969 to 1973. The demolition of the Franklin No. 10 portal and bridge was witnessed by dignitaries, miners, company officials, the public, and media, all gathered on the banks of the Green River high above the explosion. Rocket Research supplied 900 pounds of an experimental dynamite, called Astrolite K, which was placed inside the mine portal and along the mine bridge across the river. Debris from the blast washed downstream and within months there was scant evidence of the mine's existence, save for the washhouse where miners once changed clothes and showered.

Within a week of the mine's closure, the director of Washington State Parks, Charles Odegaard, wrote Jack A. Morris, president of Palmer, furthering discussions to purchase 275 acres on both sides of the river. The Franklin No. 10 and No. 12 mine sites, the former Columbia & Puget Sound railroad grade, Franklin Cemetery, and the 1,300-foot-deep shaft dug in 1902 were all part of the land and conservation easement sale which closed in April 1973.

The sale included a special dispensation allowing Frank Grens, the mine watchman, to live in the Franklin No. 10 miner's washhouse for the remainder of his life. After Grens died in November 1983, the washhouse was demolished. That area is now little more than a grassy spot on the old mine road, now a trail leading to the river.

Franklin's Hot Spring

During its decade of operation, Franklin No. 12 was prone to mine fires. After the mine closed, the coal seam spontaneously combusted, resulting in an underground fire. Heat from the fire, hundreds of feet underground, sent vents of steam and smoke up through reclaimed grassy fields east of the river. In 1972 and at later dates the dried grass caught fire, giving the property the colloquial name "burning fields." Washington State Parks bought the site in 2001 in furtherance of conservation efforts. That sale included an easement for a walking trail along a portion of a potential route from Palmer-Kanaskat State Park to Flaming Geyser.

Groundwater that flowed through the underground workings of the Franklin No. 12 mine was heated by smoldering coal, creating a hot spring. At the mine's mouth, river rafters and swimmers built a makeshift dam, creating a pool where four or so people could relax in the warm current. Temperatures were reported to be 94 degrees in 1985, with a flow of five gallons per minute. The hot-water pool was on the river's left bank, next to a steep canyon wall. It was about 10 feet above normal river flows.

Over the decades, the coal fires slowly burned themselves down so the mine waters cooled. Today, all vestiges of the pool are gone, wiped out by winter floods. Water still flows from the loose rock face, but temperatures are less than lukewarm.

The Franklin Hot Spring was a fascinating if short-lived curiosity in the mining history of South King County. Yet you can still observe the strata of the exposed 50-million-year-old geologic structure. After parking at the Franklin Ghost Town parking lot on the west side of the Green River Gorge Bridge, follow the pedestrian opening around the orange security gate. The first branch to the left accesses the Franklin No. 10 site. The second walking trail left leads down to Franklin No. 12 along a 0.4-mile footpath to a ledge on a steep bank above the river. Be mindful of dangers as rocks are slippery, river currents swift, and the waters are icy cold.

The Franklin No. 12 mine portal from which warm waters once flowed is across the river, left of and below a steep wall of dark rock and coal with trees and vegetation clinging to the cliff's edge. Also, from this viewing ledge look and listen on the right bank where another stream of water can be seen and heard. These are the waters from Randolph Creek, flowing east from Franklin Hill through the underground workings of the old Fulton No. 12 seam.

Surface Mining, Then Archaeology, Bring Renewed Attention

In 1976, Palmer Coking Coal returned to Franklin Hill and undertook surface-mining operations, first on the McKay and later on the Gem seam. Like much of Palmer's production over earlier decades, this coal was destined for state institutions like the Monroe Reformatory and Shelton Corrections Center, as the prisons continued to burn coal for heat well into the 1980s. Mining on the Gem continued until 1982 with reclamation completed in 1983. Palmer extracted its last coal in 1985 at the McKay Section 12 surface mine on the east edge of the Black Diamond city limits, often called Lawson Hill.

A few years later, Dr. Gerald Hedlund of Green River Community College, together with Mark Vernon, a research associate, undertook an archaeology project at Franklin. Over successive summers, excavations uncovered a trove of artifacts from numerous locations. Hedlund and Vernon documented their efforts in the book From Smoke to Mist, which included the story of Franklin's early years.

Renewed attention to Franklin's rich heritage produced a slew of newspaper articles. One of them prompted students at Cedar Heights Junior High in Covington to erect a sign and place a coal car donated by Palmer at a key trail intersection. In time, the Black Diamond Historical Society began annual winter tours of the old townsite, during the season when vegetation is dormant and the vestiges of mining are easier to see.

The last truckload of coal left Franklin Hill by dump truck in 1982, bringing an end to nearly a century of mining. This was 97 years after the first rail car rolled to the wharves of Seattle. During this century of mining, more than 4 million tons of coal were mined and sent to market, about one-fourth of the 16.8 million tons from nearby Black Diamond.

The miners and businessmen who established Franklin in the early 1880s had little idea what the area's distant future might hold. Ninety years later a new spirit to conserve the wonders of the Green River Gorge took hold. Today, the skeletal remains of Franklin's ghost town continue to illustrate its rich mining history, an archaeological record underscored by the natural beauty of surrounding areas.