On December 14, 1936, the United States Supreme Court rules in favor of KVOS, a Bellingham radio station, in its ongoing feud with the Bellingham Herald newspaper. Acting as the Herald's proxy, The Associated Press sued KVOS, alleging unfair competitive practices after the station began pirating content by reading stories from the Herald and two Seattle papers verbatim on its newscasts. While KVOS prevails on a legal technicality, the Supreme Court's ruling is momentous: It opens the door for news-gathering organizations such as The Associated Press to begin selling their content to radio stations.

Mortal Enemies

KVOS began in Seattle in 1927 as a 50-watt blip operated out of an apartment on Queen Anne Hill by owner Lou Kessler. Largely ignored in Seattle's growing radio market, Kessler packed up later that year and moved the station to Bellingham, where he "renamed KVOS 'The Mount Baker Station,' signed up some local live talent, beefed up the station's power and tried this and that, but just couldn't seem to take in as much money as he was shelling out. Finally he went bust and creditors ran the station until Rogan Jones and Harry Spence came up from Aberdeen and took over" (Richardson, 170).

Tennessee-born Rogan Jones (1895-1972) was a serial entrepreneur who co-owned radio stations with Spence in Aberdeen, Wenatchee, and Seattle before the Great Depression threatened to scuttle their growing empire. They purchased KVOS in 1929. Spence eventually left the partnership, most of the stations faltered, and Jones moved to Bellingham to assume active management of KVOS. According to radio historian David Richardson, "Rogan's challenge in those Depression years was to find a cheap way for KVOS to hit an apathetic community between the eyes and get its avid attention. What he came up with got the heed of not just Bellingham, but two great industries, several judges, the national press and, finally, the United States Supreme Court" (Richardson, 173).

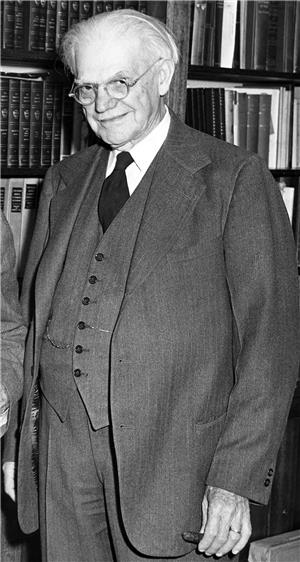

Jones began to upset the status quo when he contracted with Leslie Darwin (1875-1955), a former newspaperman and director of the state's fisheries department, to produce and star in a new radio show that covered politics and the news of the day. Darwin, a progressive Democrat, had a long and contentious history in Bellingham politics, often clashing with the city's conservative and moneyed establishment. In the 1920s he had sparred repeatedly with Frank Sefrit (1867-1950), who had succeeded Darwin as editor of the Bellingham American-Reveille in 1911, and in that same year became the editor and business manager of the Bellingham Herald. By 1933 the two had become intractable enemies.

Sefrit likewise had a long history of antagonizing his political foes. "Sefrit cut his writing chops just as a sensational writing style known as 'yellow journalism' became popular in the 1890s. Perfected by nationally known newspaper editor William Randolph Hearst (1863-1951), this style emphasized sensationalism over facts, and Sefrit was quick to adopt it. He used it to great effect to argue for causes he believed strongly in, as well as to assail his adversaries … In November 1911 he became editor of Bellingham's two largest newspapers, the American-Reveille and the Bellingham Herald" (Dougherty).

While Darwin pounded away at Sefrit on his radio show, Jones introduced another new feature at KVOS, setting aside time for three daily news shows, "thirty minutes each in the morning and at noon, and a whopping three quarters of an hour evenings. The exact times were determined after careful study of the press schedules for the Bellingham Herald's two daily editions, as well as the train and bus schedules from Seattle. The programs were called 'Newspaper of the Air,' and were unabashed readings of all the principal stories from the Bellingham Herald, the Seattle Times, and the Seattle P-I" (Richardson, 173). Not surprisingly, the newspapers -- which acquired much of their content through paid subscriptions to news-gathering services such as The Associated Press -- were mortified that KVOS was now co-opting their content and giving it away for free on the radio. Lawyers were quickly called in and the legal saga began.

Into the Courts

In 1934, Sefrit and Herald owner Sam Perkins, along with the owners of Seattle's Times and Post-Intelligencer, compelled The Associated Press to sue KVOS for unfair competitive practices. Their argument was straightforward: The radio station was pilfering the newspapers' content and giving it away, often before the newspapers themselves had arrived on subscribers' doorsteps. Arguments were heard in December 1934 in federal district court, where KVOS lawyer Clarence Dill (1884-1976), a U.S. Senator from Spokane, contended that the station was merely fulfilling its legally mandated obligation to be of public service. Judge John Bowen agreed. "Once news reports are published and distributed to the public, Bowen held, they 'from that moment belong to the public.' And KVOS was part of 'the public'!" (Richardson, 174).

The surprise victory for KVOS was short-lived. In 1935 the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals overturned Bowen's ruling and granted a preliminary injunction that prohibited KVOS from "appropriating and broadcasting any of the news gathered by the AP for the period following its publication in complainants' newspapers, during which the broadcasting of the pirated news to KVOS's most remote auditor may damage the complainants' paper business of procuring or maintaining their subscriptions and advertising" ("'Piracy' of News Before High Court"). The preliminary injunction, which the AP sought to make permanent, restrained KVOS from broadcasting the news until 18 hours after it was published.

The case -- KVOS, Inc. v. Associated Press -- was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington, D.C., where the Court heard arguments on November 11, 1936. Olympia lawyer William Pemberton, representing KVOS, asserted that the AP had suffered no damages, and that KVOS was not a competitor of the press association. Pemberton further argued that the federal court system lacked jurisdiction because the amount in controversy did not exceed $3,000. In a unanimous decision rendered on December 14, the Court agreed, and threw out the AP's complaint. Thus, KVOS "prevailed in what amounted to a technicality over a jurisdictional question: the AP, Pemberton successfully argued, had failed to provide a concrete assessment of monetary damages inflicted by having its news read on the air, partially because it operated as a news cooperative" (Judd, 124).

The ruling had wide-ranging impacts on the news media. "Rather than lead to the destruction of the Associate Press, as AP attorneys had warned, it paved the way for the sale of news material from the likes of AP to radio stations across the country, putting radio news on an equal footing with printed media" (Judd, 124). In addition, radio stations were now free to legally repeat stories written and reported by newspapers immediately after publication.

Epilogue

Sefrit continued to rail against KVOS, Jones, and particularly Darwin, in the years following the Supreme Court's ruling. The Herald protested to the Federal Communications Commission when KVOS sought to have its broadcasting license renewed in 1936, and to save his station, Jones agreed to a negotiated compromise in August 1937 that forced him to drop Darwin's inflammatory radio show. "The license for KVOS was renewed on a provisional basis later that year. Sefrit and Perkins had lost a media battle, but could claim a victory in a long-running personal vendetta against the irascible Darwin" (Judd, 122).

Having lost his platform and voice in Bellingham, Darwin moved to Thurston County in 1939 to manage rental properties. He returned to Bellingham in 1954 and died the following year at age 80.

Meanwhile, Jones continued to innovate and push boundaries. "During the 1950s he attracted further controversy through his creation of International Good Music (IGM), a centralized service providing recorded music and radio shows for broadcast around the world. In 1964 the American Academy of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) sued IGM and recipient stations, arguing that IGM broadcast music without their permission or that of the artists. The case was decided in favor of IGM" ("Rogan Jones Papers, 1912-1983"). In 1953 Jones founded KVOS-TV in Bellingham, an international station heavily viewed in British Columbia. He died on April 27, 1972, at age 76.

Sefrit, who was diagnosed with cancer in the late 1940s, wrote his last series for the Herald in 1949 and died on May 27, 1950. His sons Charles (known as "Chick") and Ben, who had both worked at the Herald since the 1920s, stepped in and helped run the paper until 1970. In 1952, the U.S. Forest Service named a 7,191-foot-high peak in the Mount Baker Wilderness after Frank Sefrit.