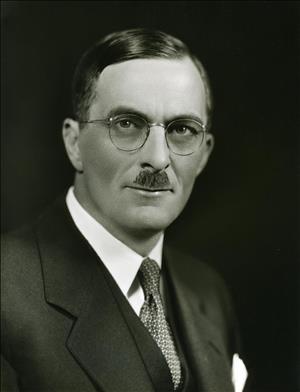

Clarence Martin served as Washington's 11th governor between 1933 and 1941. Elected near the nadir of the Great Depression, he proved to be one of the state's most effective governors of the twentieth century. A conservative Democrat who championed the common man, Martin advocated for a number of economic and social-relief programs to bring the state out of its economic slump, while at the same time keeping the more liberal, big-spending members of his party at bay. He pushed for the creation of the state's first social security and unemployment programs, and when Prohibition was repealed early in his first term, he called for the formation of a state liquor control board, which continues to regulate the state's liquor sales in the twenty-first century.

Early Years

Clarence Daniel Martin was born in Cheney, Washington Territory, on June 29, 1886. He was the second child of Francis Martin (1858-1925) and Philena Fellows Martin (1861-1919) and had an older sister, Nina Belle (1882-1973). He grew up in Cheney and attended the University of Washington in Seattle, where he participated on the debate team and was active socially on campus. After he graduated in 1906, Martin returned to Cheney. In 1907, he helped his father and J. F. Smith (his father's business partner) establish the F. M. Martin Grain and Milling Company in Cheney. The company prospered, and Martin became president and general manager after his father died in 1925. The year 1907 was significant for Martin in another way: On July 18, he married Margaret Mulligan (1886-1968) and they had three sons: William "Bill" (1909-1967), Clarence Jr. "Dan" (1916-1976), and Francis "Frank" (1919-1980).

Martin's first foray into politics came in 1915, when he was elected to the Cheney City Council. In 1928, he was elected mayor of Cheney and served until 1936, well after he became governor. (He commuted to Cheney episodically to take care of town business. Cheney was small enough -- 1,335 residents in the 1930 census -- and Martin was popular enough that his system worked.) He also was active in a behind-the-scenes way in state politics by the early 1920s, and he was elected chairman of the state's Democratic Committee in 1923.

He was still largely unknown in Washington when he decided to run for governor in 1932. It was the third year of the Great Depression, and economic conditions worldwide were growing more and more precarious. As the primary approached in September, The Seattle Times penned an apt description of the candidate:

"Clarence Martin has emerged with rather startling suddenness from the political backwoods ... Four years ago, when jazz was the rage, socially, financially and politically, Martin would not have fitted in the political picture. He was a modest, unassuming, mild-mannered small town business man out of sympathy and out of step with high-powered political ballyhoo ... But today, with the trend back toward the home and more wholesome things of life, Mr. Martin is in his element, relishing his fight for the needs of the plain people. While he regards himself as a 'hick' speaker, short of oratory and the platform tricks of practiced politicians, Mr. Martin is attracting and winning big crowds by his simplicity, his sincerity and his Main Street horse-sense. Moreover he is helped by a colorful personality, being more than six feet tall, fairly thin, rather dark and energetic" ("Two Young Men ...").

First Term

Martin won the Democratic primary by less than three percentage points, but he won the general election by a 23-percent margin over Republican John Gellatly (1869-1963), which was magnified to some extent by a Democratic sweep statewide. He became the first governor elected in the state who had been born in Washington, albeit when it was still a territory. He was inaugurated on January 11, 1933, and in his inaugural address he impressed his audience by outlining a detailed program designed to bring the state out of its economic slump. He moved quickly on his agenda, which included a combination of tax proposals and trimming the state's budget via salary cuts and layoffs. He advocated for a statewide social security program for the elderly, known as the old-age pension, which the legislature passed and Martin signed into law weeks after his inauguration. (This legislation was not new. The state had tried unsuccessfully to enact similar bills in four separate attempts dating back to 1925.) He also supported the creation of an unemployment compensation fund in the state, which the legislature approved in 1935.

Martin faced a crisis with the state's banks in the early weeks of his administration. There had already been several panicked runs throughout the country on banks, and more than 5,000 of them had closed in the United States since the onset of the Depression in October 1929. As the winter of 1933 dragged to a close, another run on banks -- many which lacked sufficient reserves because of numerous loan defaults over the preceding three years -- forced more of them to close, which panicked the public further. In order to quell the alarm and give the banks an opportunity to recover, Martin announced a closure of all state banks on the evening of March 2 for a three day "bank holiday," which incoming U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945) subsequently extended through March 13. During this period Congress passed and Roosevelt signed the Emergency Banking Act, which increased federal oversight over the nation's banks and helped stabilize the country's banking system.

Martin argued for the reorganization of what was then a relatively weak highway patrol with limited authority, and this led to the formation of the Washington State Patrol in 1933. He also pressed for the reorganization and modernization of the state highway department, which was still relying on county levies for funding. This system had worked in the earliest days of automobile travel, but with both personal and commercial traffic rapidly expanding by the 1930s, Martin favored a more centralized funding source to be paid by gasoline taxes. He closed his first year in office by calling a special session of the legislature in December 1933 to draft legislation for state liquor-control laws after Prohibition was repealed, which resulted in the formation of the Washington State Liquor Control Board the following month. In his address to the special session Martin called for strict state control of liquor sales, which remained the law until the monopoly was eliminated and private sales allowed by the passage of Initiative 1183 in 2011.

He favored tax increases, a bone of bitter contention in the Depression-ridden 1930s. He supported the income tax initiative that had been approved by Washington voters in the 1932 election, but it was subsequently ruled unconstitutional by the Washington Supreme Court. (Ninety years later, the state still has no income tax.) He proposed a business and occupation tax, which the state supreme court similarly rejected. Martin was more successful with a 2 percent retail sales tax, which took effect in May 1935. Not all state citizens reacted favorably to this sales tax. Because the tax added to a purchase often resulted in a fractional amount of a cent being due -- and because a penny was considered a much bigger amount in 1935 than it is now -- the state issued aluminum tokens, each with a value of one-fifth of a cent, to cover the fractional amounts. On more than one occasion when the governor was in public, an angry Washingtonian threw tokens at him.

Second Term

Martin ran against former governor Roland Hartley (1864-1952) in the 1936 general election and beat him by a margin of 69 to 28 percent. His victory was amplified by another solid Democratic showing overall, as well as by crossover Republicans who liked Martin's economic policies. Aided by enormous Democratic majorities in both the state house and senate, 20 of Martin's 28 requested measures passed in 1937. These included bills that established a state department of social security, provided special education facilities, expanded public aid to cover the blind and otherwise dependent, authorized state funding for junior colleges, and provided aid for public libraries. One of his few setbacks came when he was unable to convince the legislature to establish a system for labor dispute arbitration to soothe the state's seething labor problems.

Martin was similarly successful with many of his requested measures in the 1939 legislature. His request for stricter eligibility requirements for the state's old-age pensions passed, his request for increased sales taxes passed, and other tax increases -- for example, an increase in cigarette taxes and an extension of the sales tax to liquor -- were approved. In 1939 a new department of unemployment compensation became operative, and qualified persons began receiving their first checks; Martin had specifically requested that the department be established. He also issued an executive order for a 15 percent cut in code department spending and reduced appropriations for the state Works Progress Administration, which led to layoffs at the agency. His fiscal moderation had become so legendary by the late 1930s that some of his fellow Democrats referred to him as "the best Republican we ever elected" (Newell, 402).

He was a strong proponent of public-works projects to create jobs as a remedy to the widespread unemployment resulting from the Depression. At his urging, the legislature created the Columbia Basin Commission, which led (with federal assistance) to the construction of the Grand Coulee Dam, which began operation in 1941. He supported the Lake Washington Floating Bridge project, completed in 1940, as well as the Tacoma Narrows Bridge, which first opened in 1940 and collapsed the same year. His administration continued and expanded the road-improvement projects begun in earlier years as the automobile gained traction in American society, which not only provided jobs during the Great Depression but resulted in the construction and improvement of many state highways, some which are still in use today.

No account of Martin's eight years as governor is complete without an honorable mention of his lieutenant governor, Victor "Vic" Meyers (1897-1991). Meyers was everything Martin was not: flamboyant, fond of publicity, friendly with the more liberal elements of the Democratic party (who Martin had little use for), and not above a little sleight-of-hand if necessary. He was a constant thorn in Martin's side, as was vividly demonstrated in 1938 when Meyers was pressured by the liberal wing of the legislature to call a special session while Martin was out of the state and Meyers was acting governor. The problem was that Meyers was out of the state too, and he had to be physically present in Washington to have the requisite authority. The lieutenant governor and the governor both raced for home, Meyers from Southern California and Martin from Washington, D.C., while the Seattle press eagerly covered the drama. Meyers beat Martin to the state capitol but arrived too late in the day to file his proclamation for a special session. When he returned the next morning he learned that the governor's plane had just touched down in Spokane, robbing him of his moment in the sun.

Though Martin was a popular and effective governor, there was a general sentiment that he should not run for a third term in 1940. The biggest argument seems to have been that he had served two full terms and it was time to move on; similar arguments were being made against President Roosevelt that year. Nevertheless, the governor pursued a third term, perhaps believing that crossover Republicans who had supported him in the past would make up the difference of any Democrats who might defect. Not only did that not happen, but Democrats, especially those east of the Cascade Mountains who had been dependable Martin voters in 1932 and 1936, deserted the governor in droves. He lost in the primary that September to former U.S. Senator Clarence Dill (1884-1978) by a margin of more than 13 percent.

In his farewell address to the legislature on January 14, 1941, Martin reviewed his accomplishments and setbacks and said he felt his greatest accomplishment was getting social security established in the state. He recommended increased funding for public assistance and again renewed his call for a state income tax for those with higher incomes, arguing it would make a more equitable tax program and help balance the state budget. And he gave his lieutenant governor a special sendoff. The debonair Meyers flippantly asked the more-staid Martin for a goodbye kiss, doubtlessly expecting a polite rebuff. But the governor didn't miss a beat. "Sure," he said, giving Meyers a hug and a smack on the cheek, while the audience laughed in glee.

Martin left office the next day to rave reviews. The Seattle Times gave him a grateful compliment:

"Fulsome praise of Governor Martin seems needless; but the people may well pause in gratitude to think what might have been done to them, and how much more wildly their state government might have capered during the past eight years, under a governor less unselfish and fearless, to say nothing of one less honest than he" ("What Might Have Been").

Later Years

Martin returned to Cheney and resumed managing his grain and milling company. He sold the mill to the National Biscuit Company in 1943, but he and his family retained their interests in the company assets themselves, which included business and real estate throughout the state. Later that year, he and his wife Margaret divorced. In February 1944, the Spokane County Commissioners appointed Martin to a vacant seat in the House of Representatives, representing the 5th Legislative District when the legislature held a special session. The session, which was called to provide absentee voting rights to the servicemen fighting overseas in World War II, lasted only six days, and Martin did not seek to retain the seat afterward.

Shortly after the special session ended, Martin married Merle Lewis and moved to Southern California. The couple divorced in 1946, and he returned to Cheney. In 1948 he entered the governor's race on the last day of filing, arguing that the present governor, Monrad "Mon" Wallgren (1891-1961), had mismanaged the state's finances and was too cozy with labor. But this time his message failed to resonate, and some Democrats felt that by pointing out Wallgren's faults in the primary, Martin was handing the Republicans ammunition against the Democrats in the general election. Just as The Seattle Times had said in 1932 that Martin would not have been the right man for the job in 1928, so perhaps that was true in 1948. He lost in the primary to Wallgren that September by more than 10 percentage points.

Martin married Lue Eckhart in 1951, the same year that he began to show symptoms of Parkinson's Disease. He kept it quiet for the next several years and continued managing his varied interests, which included serving on the Cheney City Council from 1950 to 1952 and serving on the board of Directors of Seattle First National Bank from 1942 until 1955. By the spring of 1955 his illness had progressed to the point that he was forced to stop working, and it was then that his condition became known to the public.

Clarence Martin died of respiratory failure at his home in Cheney on August 11, 1955, leaving a legacy of having brought Washington fully into the twentieth century and helping provide its government with many of the tools it needed to succeed in the new era.