A magnet for collectors and curiosity seekers, history buffs and bargain hunters, Ye Olde Curiosity Shop has thrilled visitors from Seattle and around the world for more than 120 years. Its founder, Joseph Edward Standley (1854-1940), was as colorful and eccentric as some of the curiosities he displayed. Standley arrived in Seattle in 1899 by way of Denver, opening a shop at 2nd Avenue and Pike Street originally called Standley’s Free Museum and Curio. The name went through several iterations before it became Ye Olde Curiosity Shop around 1907. Its location varied as well, although it was never far from Seattle's central waterfront. Buoyed by scores of explorers, traders, and whalers eager to sell souvenirs from their journeys, as well as the international success of the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, Ye Olde Curiosity Shop quickly became an integral part of Seattle waterfront history. The shop attracted hundreds of celebrities and collectors, locals and lookie-loos fascinated by shrunken heads, carved masks, Native artifacts, mummies, and other curiosities. Standley died in 1940, but the shop was still operating in 2022, run by a fourth and fifth generation.

A Life-long Interest in Curios

Joseph Edward (J. E.) Standley was born February 24, 1854, in Steubenville, Ohio, about 33 miles west of Pittsburgh, along the Ohio River. He was the youngest of six children; his father owned a butcher shop. As a boy, he enjoyed going down to the riverfront to buy or trade baskets from boats on the Ohio. According to family lore, his interest in collecting was spurred by a book on the wonders of nature that he won for having the neatest desk in his elementary class. The book’s tales of adventure got him dreaming about wild places and Native peoples, and he would often search the riverbank for arrowheads and fossils. "He would cross the river and wander through the big hills and in the deep caves of West Virginia to study Indian lore. That was the real beginning of his desire to seek the curios" ("Seattle Man Collects Curios").

At the age of 21, Standley left Ohio, eventually ending up in Denver, where he owned a small grocery and confectionery. His customers included Native Americans who lived nearby, as well as frontiersmen like William Frederick "Buffalo Bill" Cody (1846-1917), who sometimes stayed at the nearby Alvord Hotel when his Wild West show was in town. Some of the Native customers would pay for their supplies with baskets or trinkets, and Standley used them to decorate his store. Customers thought they were for sale. "People began to buy them. So I got more and more curios," he said (1001 Curious Things, 15).

Standley married Isabella A. Rounds (1856-1920) in 1876 and the couple had a son, Edward (1882-1945), and three daughters: Jessie (1879-1963), Carolyn (1880-1967), and Ruby (1892-1970). When Isabella started having health issues in the Mile High City, the couple decided to move to a lower altitude. In 1899, at the age of 45, Standley and his family moved to Seattle, where he turned his collecting hobby into a full-time job.

On The Waterfront

Standley arrived in Seattle at a time when the city was booming. "Transport to and from Alaska was well established and men traveling there could bring out thousands of Native relics to pass on for quick cash. The extension of James J. Hill’s Great Northern Railway to Seattle in 1893 had established a link with rail transport across North America ... Increased efficiency in transportation also meant that sailors and tourists, as well as local residents, furnished a ready audience for a vicarious experience with the exotic that the shop would provide. A shop of curiosities offering something for everyone could thrive in a city such as Seattle" (1001 Curious Things, 19).

Standley opened his first shop at Second Avenue and Pike but decided a waterfront location made more sense. There he could cherry-pick curiosities coming in by boat from Alaska and Pacific Rim nations, and it would place him closer to the tourists arriving by sea. He found property at the foot of Madison Street below 1st Avenue, where he built a small wood-and-tin building to house his shop, now called The Curio. To attract customers, he hung baskets and carvings outside its windows and front door.

When the block was slated for demolition in 1904, he relocated the shop to Colman Ferry Dock at Pier 52. His establishment was now called Curiosity Shop and Indian Curio, eventually shortened to Ye Olde Curiosity Shop, a reference to the Charles Dickens’s 1841 novel, The Old Curiosity Shop. "The reference was familiar to the public and Standley advertised that his shop actually 'beat the Dickens' ... Along its sides the small steamboats of the Mosquito Fleet landed passengers, cargo, and mail. It was an excellent location, actually on the waterfront, where there was always pedestrian traffic" (1001 Curious Things, 27).

Thanks to Standley’s business smarts and his eye for collecting oddities, the shop did well, and by 1906, the family moved from a downtown apartment to a home in West Seattle at the corner of California and Palm, which he called Totem Place – aptly named since Standley had installed nine totem poles (average height of 14 feet) on the grounds. Inside, the home was chockablock with objects and curiosities. A 1925 article in The Seattle Times provided a partial listing: "monstrous whale ribs, a Chinese Mandarin sundial, Indian family totem medallions, Igorotte war shields from the Philippine Islands, 135-pound giant clam shells, a chair made from Elk horns, vertebrae of a whale, Chinese 'suey' jugs, elaborately carved chairs from Chinese teak and hundreds of other articles each with a historical or sentimental value have been collected" ("Seattle Man Collects Curios").

A further boost to business came with the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, which opened June 1, 1909. Similar to a world's fair, the expo was charged with promoting the economic potential and natural appeal of the Pacific Northwest. Standley provided more than 1,200 items for display in cases in the exposition's Alaska Building and received a gold medal for his efforts. More than 15 million visitors attended the 138-day fair, a significant marketing opportunity for the relatively new business owner.

Many years later, grandson Joe James remembered how Standley came by some of his merchandise: "My grandfather said that you could see the Indians coming across the bay in their canoes with their wares and they’d come to the back of the shop ... They’d bring all their things up and put them on the dock and he’d go out there with the money in his hands and he’d put a quarter on each basket, or a half or one dollar, or whatever it was, it wasn’t too much in those early days" (1001 Curious Things, 56).

Moose Heads to Mummies

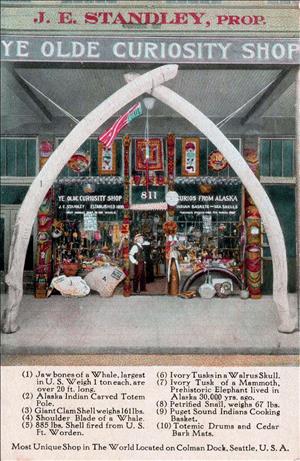

Standley’s shop carried a mind-boggling array of objects, appearing to take up every square inch of the space, from floor to rafters. There were moose heads and tiger skins, armadillo-shell sewing baskets, a tugboat made out of matchsticks, and a grain of rice on which had been inscribed the Lord’s prayer. The store also displayed and sold items of more cultural significance, such as Northwest Coastal totem poles, woven cedar mats, carved masks, and fir-needle baskets. Even the entryway was dramatic: Customers entered through an arch formed by two half-ton whale jawbones.

Standley often had a thrilling story to accompany the acquisition of an object, including the jawbones: "I found them in 1908, on a beach thirty miles north of Cape Race Light on Vancouver Island. One was in the water and the other was in the sand, half buried. I didn’t know how to get them to Seattle. But finally I gave some Indians ... five dollars to bring them to Seattle. They built a raft, put stones on it and sank it near one whalebone at low tide. They lifted the bone, which was lighter under water, up on the raft and then took the stones off. It rose right to the surface. They waited until high tide and got the other bone on the raft, and then they sailed the whole business to Seattle" ("Waterfront Back to Normal").

Whether the objects were big or small, bona fide artifacts or bizarre curiosities, Standley never lost his fervor for collecting and showing off his wares. "One is made welcome by the joyful interest he seems to feel as he ushers you about showing you curios. He beams genially as does the amused onlooker while displaying his dressed-up flea for the millionth time. One may leave Ye Olde Curiosity Shop empty handed, but never empty headed or hearted" (1001 Curious Things, 149).

The Guest Book

Almost from the beginning, Ye Olde Curiosity Shop was a must-see attraction for visitors and local residents alike. Standley, by this time called "Daddy" Standley, proudly kept a guest book for famous individuals to sign. Over the years, these included presidents Warren G. Harding (1865-1923) and Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919), dancer Irene Castle (1893-1969), Queen Marie of Romania, boxer Jack Dempsey (1895-1983), FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover (1895-1972), and actors Charlie Chaplin (1889-1977) and Jean Harlow (1911-1937). President Roosevelt’s eldest son, Teddy Jr. (1887-1944), once stopped in the shop on his way back from a bear hunt in Alaska.

But it was not just presidents and celebrities who frequented Ye Olde Curiosity Shop. Collectors and museum directors from around the world relied on objects from Standley to build or augment their own collections. George Gustav Heye (1874-1957), whose extensive collection of Native American artifacts would later form the basis of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian, purchased more than 1,200 artifacts – in fact, most of the items that were displayed at the Y-P-E Expo – for his Museum of the American Indian, which broke ground in 1916. Heye continued to buy from Standley over the years, sometimes driving cross-country in a limousine. He was often an overnight guest at the Standley’s West Seattle home.

Other museums followed in Heye’s footsteps. The Royal Ontario Museum of Archaeology and the Newark Museum made substantial purchases of Arctic and Northwest Coastal art. Portland Art Museum, Burke Museum of Natural History, Stockholm Museum, British Museum, and many others, were customers, as well. Standley also was popular with a select cadre of wealthy, sometimes eccentric, collectors. L. Robert Ripley (1890-1949), of Believe It or Not! fame, spent $1,000 at Ye Olde Curiosity Shop in 1936, an enormous sum for that era. At one point, Ripley bought a 37-foot totem pole, a giant 200-pound clamshell, and the elaborately carved wooden Potlatch Man to decorate his upstate New York mansion and its manicured grounds.

"A One-Man Chamber of Commerce"

Firmly established as proprietor of a tourist mecca and the "most unique shop in the world" ("Signs Needed to Aid City’s Guests in Finding Places"), Standley did not shy away from promoting his business and his adopted hometown. "Eighty-six years old, Standley is a kind of one-man Chamber of Commerce, abreast of the times, eager to do all he can to aid the city of Seattle, whether the means be great or small" ("Strolling Around The Town"). He was always full of advice regarding untapped promotional opportunities. In a 1933 Seattle Times interview, he suggested the city needed to do a better job of boosting tourism. As he put it: "Seattle should do a little more to encourage the tourist to stay in town after he gets here. One way would be to hang upon the streetcars a card such as: 'This car to the Rose Gardens (2 acres) in Woodland Park' ... These signs would advertise the city and help the street cash receipts" ("Signs Needed to Aid City’s Guests in Finding Places:).

On another occasion, he chastised the Seattle police force for allowing traffic jams to occur on Alaskan Way near his shop. In a 1937 letter to the chief of police, Standley wrote: "Something should be done at once to handle the fast-increasing traffic on Alaskan Way on the central waterfront. If you will come down in front of the new Colman Dock ferry terminal at 6 p.m., you will think a riot was on in full blast, and not a traffic officer in sight ... We sure need stop lights and the best man in your command to be out" ("'Dad' Standley Warns Police Chief ..."). His letter got results – a traffic light was quickly installed at Marion Street and Alaskan Way – but it was not enough to keep Standley out of harm's way. The day after the light was installed, the 83-year-old was struck by a car as he tried to cross the street and suffered a broken leg.

A Family-Run Enterprise

Bald and small in stature, often sporting a little black skull cap, Standley was hardworking, physically robust, and mentally alert well into his eighties. On his 86th birthday, he told The Seattle Times: "Still tough and healthy. Look at that fist – like a blacksmith's. Look backward. Not me! Too many things to look forward to. I'm still working in the store. Still seeing people. Still going down to a show Saturday nights – alone, too. Look backward? Why forty-one years ago, when I opened my store on the waterfront, this was the deadliest, dirtiest town in the world. Wooden sidewalks with big nails sticking up in them ... Nothing but a bunch of rusty tin warehouses full of flies and rats on the waterfront. Now look at it. I like progress" ("'Daddy' Standley, 86, Today, Refuses Flatly to Look Back").

Less than a year later, the 86-year-old Standley started feeling poorly and on October 23, 1940, he was taken to the hospital for blood transfusions. He died of pneumonia on October 25. His son, Edward, ran the shop until Edward's death on September 2, 1945, then Standley’s daughter Ruby and her husband Russell James took over. Russell James died in 1954, and his son, Joe James (1924-2016), who started working in the family business by sweeping floors when he was 12, became store manager.

One of the most popular curios acquired mid-century was the mummy nicknamed Sylvester. According to the story, Sylvester was leaving a poker game in Gila Bend, Arizona, in the 1880s on horseback when he was shot by bandits, stripped of his valuables and clothing, and left for dead. "According to the tale, he dried out so quickly in the relentless sun that his desiccated corpse was saved from corruption for all eternity ... The detail is amazing: eyelashes, fingernail, texture of skin" ("Doctor Peg and the Ye Olde Curiosity Shop").

In 1963, Ye Olde Curiosity Shop moved into a new building on Pier 51 that resembled a Native American-style longhouse designed by Paul Thiry (1904-1993), principal architect of the Seattle World's Fair. In his design proposal, Thiry indicated he wanted to retain the original atmosphere of the shop but with a more Northwest flair: "It should be a combination of a long house, with marine characteristics and even the old mill design of Yesler’s pioneer mill. The shop should be of wood for a pioneer area ... and should look like a waterfront shed. The timbers inside can hang articles from the roof as in the old structure, giving the visitor the feeling that the thousands of curious have been there forever. It should have both a treasure and museum character" (Evans). For 25 years, Pier 51 housed the shop, the most time it remained in one location. In 1988, it moved again, this time to Pier 54, where it remained in 2022.

Like his grandfather before him, Joe James was a civic booster, active in the Rotary Club, Seafair, and the Seattle Tourist and Convention board. After his death in 2016, his son Andy and wife Tammy became proprietors of Ye Old Curiosity Shop, assisted by sons Neal and Justin. By this point, the majority of the shop’s wares skewed more towards tourist kitsch and stocking stuffers such as whistles, coffee mugs, tee shirts, postcards, seashells, and shot glasses. Shrunken heads are still available, but in rubber only. Sylvester the mummy remains on display in a large plate-glass case, with a second mummy, a female nicknamed Sylvia, close by.