From its founding in 1852, Seattle has been confronted by the scourge of homelessness. The city's first official homeless person was Edward Moore, a Massachusetts-born sailor who, having been rescued from a makeshift tent on the city's waterfront, was deemed insane and unable to take care of himself. In this essay about Moore for HistoryLink, Josephine Ensign, a Professor of Nursing at the University of Washington, details his tragic life and examines the laws, customs, and ethics that governed homelessness in the city's infancy.

Lost on Little Prairie

Late December 1854 in Seattle was relentlessly cold and wet. Sleet slashed horizontally across the beach, encrusted piles of seaweed, kelp, and driftwood on the high-tide line, and worried its way through the flaps of a tattered canvas tent nestled between charred tree stumps, and onto the muddy rag-wrapped feet of the shivering man lying inside. The man's tent was the only such structure on this stretch of shoreline along the northern edge of the settlement, on land newly claimed by William Bell but known to both white settlers and Native Americans by its Coast Salish name, babaqwab (Little Prairie), named for its stretches of berry-producing salal. Piles of clam shells surrounded cedar Indigenous longhouses, as the beach here was rich with butter clams.

The tent-dweller’s name was Edward Moore, a 32-year-old sailor from Worcester County, Massachusetts, who stayed behind in Seattle -- or was left behind by his ship's captain. Perhaps he drank too much even by drunken-sailor standards, although there is no record of that. What is known is that he had been living in this makeshift tent for months, living off raw shellfish he foraged.

Soon after this December day, Edward Moore was deemed by the white leaders of Seattle as insane and incapable of taking care of himself. They likely found him in his tent, unable to walk, and carried him through frozen mud along the beach at low tide to the town’s one rooming house. There was no hospital. They discovered that he had severe frostbite of his feet. The town’s first doctor, David Swinson Maynard, amputated most of Moore's toes with an axe. Doc Maynard may have sterilized the axe with the whisky he was fond of drinking. Moore survived this primitive surgery, was cared for by Doc Maynard, Maynard’s second wife and Seattle’s first nurse, Catherine Maynard, and the German immigrant innkeeper, David Maurer. Edward Moore became Seattle-King County’s first official insane pauper — Seattle’s first homeless person.

The Village of Seattle

The settler colonial village of Seattle was barely two years old, and consisted of less than a dozen log and wood-frame houses scattered along the shore just south of where Moore was found. Seattle was built on an eight-acre isthmus of marshy land near the mouth of the Duwamish River where it enters Puget Sound. The white settlers called the area either "The Point" or "The Sag." At high tide the town was an island, but the low-lying tidal marsh around it was being filled by piles of sawdust from Henry Yesler’s steam-powered sawmill. The mill was the area's only industry and Yesler employed male settlers and a considerable number of local Indigenous people. The cookhouse at Yesler's mill was the center of town activities, serving as the early courthouse, church, and saloon, as well as a place to feed and sometimes house the loggers. Yesler's cookhouse was likely where the townsfolk gathered on that December day in 1854 to discuss what to do with Edward Moore.

The residents of Seattle knew of Moore before he was found half-frozen on the beach, as he had become a wandering, destitute fixture in the village. After the crude amputation of Moore’s frozen toes, Doc Maynard and his wife Catherine took him into their home to care for this "stranger, and insane besides" (Morgan, Skid Road, 36). Accounts reveal that together they helped restore Moore’s physical health to a large extent, but not his mental health.

Poor Laws

Who is responsible for paupers, for insane people, for homeless people? Besides the moral imperative to assist people less fortunate, there have long been legal imperatives directed at both the family and public levels. The first settlers of what became Washington state carried the Poor Laws with them across the prairies from places like New England and the Midwest. These Poor Laws were state, or in this case territorial, laws originally derived from the sixteenth century Elizabethan English Poor Laws adopted by the early American colonies.

The English Poor Laws began with the late Medieval "Vagabond and Beggars Act of 1494," which called for all male and female vagabonds and beggars to be put in the stocks for three days and nights, given only bread and water, and then "warned out" — admonished to return to the "Hundred" (parish or township) where he or she was born or last lived. Vagabond and beggar repeat offenders could be and were executed. These Poor Laws were expanded through the passage of the "Act for the Punishment of Sturdy Vagabonds and Beggars" in 1536, which in turn became the Elizabethan Poor Laws codified between 1597-98, and signed by the Parliament in 1601 as the "Act for the Relief of the Poor." For the first time in England, the state, and not the church, was responsible for management of the poor, including the levying of parish-based taxes to pay for poor relief.

The "warned out" portion of the older law was extended under the Elizabethan Poor Laws and became known as the Act of Settlement, which banned the poor from moving anywhere outside their own parish, even if they were in search of work. This severely limited the geographic and socio-economic mobility of the poor. It is worth noting that these laws were made by the landed gentry, who had a vested interest in maintaining a pool of local laboring poor people to perform low-paying, dangerous, and unpleasant work.

The Elizabethan Poor Laws established the duty to support, mandating that the primary responsibility for the care and support of a poor person was that person's family. It stipulated the rule of three generations, meaning that the pauper's parents, grandparents, and children were morally and legally responsible for the care of "their own." If the poor person's family either did not exist or could not support their family member, the local parish could auction off the care of the pauper to the lowest bidder at a public auction. A poor person receiving parish support was required to wear a branding on their clothing that identified them as a charity case. Able-bodied or "sturdy" paupers — as compared with the "impotent poor" who could not work — were regularly rounded up and shipped off to the increasing number of English colonies around the world, including the colonies in America.

The early American Poor Laws continued state and territory-level variations of the Elizabethan Poor Laws, including the Law of Settlement and warning out or passing on of poor people considered to be outsiders to a parish or county. This has been described as the guiding principle of "Help thy neighbor and expel the stranger."

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries in the expanding American states and territories, paupers continued to be denied political, civil, and social rights. Poverty was considered an individual and not a societal or economic systems-level failure. The Poor Laws supported the view of poverty as a crime, especially for the "undeserving poor," a category that included any pauper, no matter their age, gender, or condition, deemed by the authorities as able to perform some type of work. And because the "distracted" (an early American term for insanity) and "idiots" were so often poor or vulnerable to exploitation, they were considered "deserving poor," along with the elderly, widows, orphans, and the blind.

The duty of support by family members was carried over from the Elizabethan Poor Laws. Many states expanded upon this in the early 1800s to include grandchildren as well as brothers and sisters in the moral and legal duty to financially support a poor family member. The Law of Settlement was widely adopted; it included the stipulation that counties be reimbursed by a pauper’s "home" county for any costs of support, including medical care, rendered while the pauper was within its jurisdiction.

The Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Washington passed "An Act Relating to the Support of the Poor" on May 1, 1854. This original Poor Law stayed as the law in Washington state with only minor amendments well into the twentieth century. Section One of the law stipulated that it was the duty of the boards of the counties within the Territory to be "vested with the superintendence of the poor in their respective counties." Poor persons were defined as anyone "who shall be unable to earn a livelihood in consequence of bodily infirmity, idiocy, lunacy or other cause" ("An Act Relating ..."). It was this Poor Law that the leaders of King County consulted when deciding what to do with Edward Moore, who, because of both his mental and now permanent physical disabilities, had been rendered a "deserving" pauper living in their midst.

Despite whatever mental illness Moore had, he was lucid enough to tell his various doctors and caregivers where he was from — Worcester County, Massachusetts — and that he had a wife and children who lived there. They also documented how long he had resided in Seattle-King County: less than six months from when he was found half-frozen on the Seattle beach. From this information, they decided that he was not a resident of King County. The Poor Laws of Washington Territory at that time stipulated a minimum continuous stay of six months in order for a person to establish residency. Of note, during this time, Indigenous people were not considered residents.

Transfer to Steilacoom

In May 1855, the leaders of Seattle transferred Moore 50 miles south to the town of Steilacoom to be cared for by Dr. Matthew P. Burns. Dr. Burns gave Dr. Maynard a receipt for Moore, "an insane and crippled man, a stranger without acquaintance or friends" (Prosch). Steilacoom was a larger and more established settlement than Seattle. Fort Steilacoom was there, which housed a unit of the U.S. Army formed to defend early settlers from Indians and to establish America’s Manifest Destiny claim on land still marginally occupied and claimed by England. Fort Steilacoom would become Washington's first public insane asylum in 1871, Western State Hospital, which continues in operation today.

Mental Illness

During the time that the residents of Seattle-King County were working through what to do about the care of Moore, the understanding and medical treatment of mental illness in the United States was undergoing radical change. Up until the beginning of the nineteenth century, in Europe and America, mental and physical ailments were lumped together and largely attributed to spiritual causes and were treated accordingly. Heroic measures, including bloodletting, purges, and blistering, were the main treatments for mental illness until the early part of the nineteenth century. These heroic measures were used in conjunction with restraint, including shackles, cuffs, straightjackets, and locking patients in bare jail cells when families could no longer care for the person, or when no family existed. Then, beginning with advances in France and England, and soon spreading to New England, moral treatment began to take hold.

French physician Philippe Pinel is credited with developing this new approach to mental illness treatment and with coining the term traitement moral. Pinel and other proponents of moral treatment advocated for the release of lunatics from chains and for them to live in quiet places with regimented but kindly discipline. Hence, the terms "asylum" and "retreat began to be synonymous with the insane hospital.

This sort of ideal care for the mentally ill was, of course, not available in or near Seattle in the 1850s while the residents were figuring out what to do with their first insane pauper. Seattle, and indeed the entire Washington Territory at the time, had no specific provisions or places for insane people. Ironically, Massachusetts, and specifically Worcester County where Moore was from, had one of the nation’s best insane asylums. In 1833, Massachusetts opened the country’s first state-supported public mental hospital, the Worcester Insane Asylum in the City of Worcester. Massachusetts was also home to the leading mental illness treatment reformer of the time, an intrepid reformer who would make her way west to Washington Territory: Dorothea Dix.

Starting in 1830 with her investigative reporting on the deplorable conditions of inmates at a Cambridge, Massachusetts, jail, Dix quickly spread her advocacy efforts with inspections of prisons and insane asylums throughout Massachusetts and other states, then internationally. After Dix’s stint as Superintendent of Women Nurses for the Union Army during the Civil War, she again took up her mental health reform efforts extending them to the Far West, visiting California, up through Oregon, to Washington Territory. Remarking on the natural beauty of Washington, she described in a letter to friends that she was favorably impressed by the Pacific Northwest’s "humane and liberal" prisons and insane asylums. She attributed their excellence to how newly settled the area was, a newness that allowed for more progressive thinking than in either European or the American East Coast cities.

Dix’s visit to the Pacific Northwest was soon after the time that Moore was living and being cared for by residents of Seattle and Washington Territory. At the time of her visit, Seattle-King County and all of Washington Territory were still using the contract system used with Moore — the auctioning off and contracting out of paupers and persons with mental illness. In her report to the Washington Territorial Legislature, Dix pointed out the abuses of the contract system, including the fact that many people pocketed the money and provided poor, substandard care.

Public and private debates in America were raging as to whether paupers, insane or not, brought on their own plights through immoral acts such as intemperance, specifically in terms of alcohol consumption, and the duty of the state to care for such people. Calvinist work ethics and conceptions of sin and salvation colored these debates. Women with children "out of wedlock" and prostitutes were labeled as sinners and as undeserving poor. Leading reformers such as Dix declared that the duty of society was the same whether insanity or destitution resulted from "a life of sin or pure misfortune" (Brown, Dorothea Dix, 90).

There are no indications that Moore exhibited intemperance, especially since if he had been a drinker that fact would have disqualified him from having a legitimate claim for assistance from the residents of Seattle-King County. A side note about Moore’s behavior, as recorded by M. P. Burns, the Steilacoom doctor who took over his care from Doc Maynard, was that Burns found "it necessary to keep said pauper confined hand and foot, in order to keep him from certain habits into which he has fallen and supposed to be the original cause of his present deplorable condition" (Prosch, "The Insane in Washington Territory"). It is plausible that the "cause" of his insanity surmised here is a reference to masturbation. During that time, masturbation was widely accepted in medical circles as being a direct cause of insanity and even death. People were hospitalized and treated for the disease of masturbation, also termed onanism.

Washington Territorial Legislature

In December 1855, the King County Commissioners submitted a report to the Washington Territorial Legislature requesting reimbursement for the costs of caring for "the lunatic pauper named Edward Moore" (Prosch, 3). The itemized bill they presented to the Legislature included costs for medical attendance, nursing, and board for Moore’s stay in Seattle, with the combined cost of $621. In addition, the bill included costs for payment to Dr. Burns of Steilacoom. The aggregate bill presented to the Legislature was $1,659 for the care of Moore over a 12-month period after he was found on the beach in Seattle.

In the Legislative report, it was noted that Moore was deemed a non-resident because of lack of sufficient evidence that he was a citizen of King County. They established that from what was known about Moore, he was from Worcester County, Massachusetts, and that he had family members living there. The Poor Laws of Washington Territory stipulated that "Every poor person who shall be unable to earn a livelihood in consequence of bodily infirmity, idiocy, lunacy or other cause, shall be supported by the father, grandfather, mother, grandmother, children, grandchildren, brothers or sisters of such poor person, if they or either of them be of sufficient ability ..." ("An Act Relating ...").

The Legislative committee reviewing the case of Moore decided that although his situation "should touch all the finer feelings of nature," it would be unwise for the Legislature "at this early date of our territorial existence ... to pass a law for the relief of those interested, because it would be setting a precedent that would, if carried out, bring a heavy burden of taxation on the people of the Territory" (Legislative Asembly of the Territory of Washington, 4). The total yearly income of Washington Territory from all tax revenue that year was $1,199.88, which was $459 less than the total bill submitted for the care of Edward Moore. The committee returned the issue to the King County Commissioners.

Back to Seattle

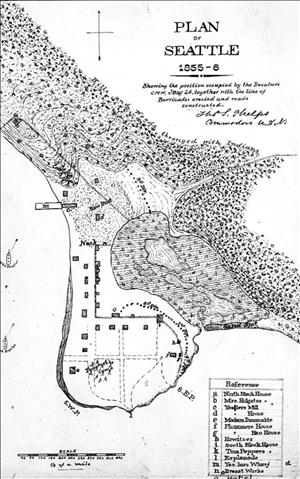

When Dr. Burns heard of the ruling by the Washington Territorial Legislature not authorizing reimbursement for his care of Moore, he promptly put Moore in a canoe, paddled him back to Seattle, and left him there. This likely occurred in early January 1856, soon after the legislature's decision, which meant that Moore was living in Seattle during the short-lived but intense Battle of Seattle. In late January 1856, at the height of the fighting between various Indian tribes defending their lands and settlers in the area staking claims to the land, the Seattle townspeople would have bundled Moore into the nearby windowless wood plank blockhouse for protection from gun and cannon fire — including "friendly fire" from the USS Decatur warship situated in Puget Sound near the wharf at Yesler's sawmill. This atmosphere would hardly have been conducive to healing whatever mental illness Moore had. Once again, he was left to fend for himself.

There are no indications that Moore was shackled or confined during his time in Seattle as he had been in Steilacoom while under the care of Dr. Burns. There are no mentions that he exhibited any violent behavior. Moore is described as "crazy," "odd," and "insane" by various physicians who treated him. Given what is known about him — especially considering what became of him — he may have had a form of psychosis, most likely schizophrenia.

Moore shows up once again in the King County records in the summer of 1856. "The county commissioners decided that Edward Moore, the pauper, now in Seattle, be sold at public auction to the lowest bidder for his maintenance to be paid out of the county treasury, said bid to be left discretionary with the Commissioners to accept or reject, on Saturday, the 7th day of June at 2 o’clock in the town of Seattle" (Morgan, 35). It appears that either no one in Seattle wanted to care for Moore, or the bids that came in were too high for the King County Commissioners to accept. Sometime later that summer, the residents of Seattle-King County collected private donations, bought Moore a new set of clothes, and paid a ship's captain to transport him back to Boston. Seattle historians who have included the story of Edward Moore, conclude along the lines of Thomas W. Prosch: "What became of him is unknown" (Prosch, 6).

But Moore’s story does not end here.

Resting Place

Fifty miles northwest of Boston, along the watersheds of the Connecticut and Merrimack rivers in the mill town of Ashburnham in Worcester County, Moore returned to live with his family members sometime in early 1857. There was no insane asylum in Ashburnham at the time of his return, but there was a town Poor Farm that had opened in 1839. According to the laws of Massachusetts, the duty to support the "insane pauper" in the Moore family would have fallen to Edward's parents and then his siblings, before the town or county stepped in to provide aid.

The forests on the hills around Ashburnham were rich in red oak and chestnut trees milled in town by water-powered machines and turned into furniture. Edward's younger sister Abigail had married Luke Marble, who owned a lumber and furniture mill in Ashburnham. Edward's elderly parents were living with Luke and Abigail. Once he returned to Massachusetts, Edward Moore most likely lived with his parents, sister, and brother-in-law in a wood-framed house near Marble Mill in Central Village Ashburnham. There is no record of Moore reuniting with his wife and children.

Edward Moore was born on January 28, 1823, in Worcester County, in the rural village of Boylston, less than 30 miles from Ashburnham. He died in early May 1859 in Ashburnham, only a few years after he had been shipped back home by the residents of Seattle. His official death notice lists his date of death as May 12, 1859, with the cause of death "suicide by hanging (cause insanity)." In the death register, he is listed as being the son of Pitt Moore, married, and without an occupation. He is buried beside his parents in the old cemetery on Meetinghouse Hill in Ashburnham. His gravestone is engraved with "Edward Moore Deceased May 11,1859 AE. 36 yrs. 3 ms. 13 ds" (AE being Latin Aetatis, or years of life.)

The date of death on his tombstone and in the official death record differ by one day. Perhaps his family knew that he killed himself on Wednesday, May 11, but his death wasn’t certified by a town doctor and registered by the town officials until the following day.

Would Moore’s life have been better, and longer, if he had stayed in Seattle and not been sent back to his family in Massachusetts? Was his initial episode of almost freezing to death while living on the Seattle beach an early suicide attempt?

These questions, along with many others about the life and death of Edward Moore, Seattle’s first homeless person, remain unanswered. We are left with fragments of Moore’s life that woven together do not lend themselves to a neat conclusion. Yet, his legacy remains. His life influenced how the residents and officials of Seattle-King County dealt with the quandary of what to do about the increasing number of ill paupers and homeless people living, and dying, in their midst. What became of Edward Moore, how the residents and leaders of the nascent town of Seattle dealt with him, and the poignant story of his final days, echo lessons and dilemmas that are with us still.