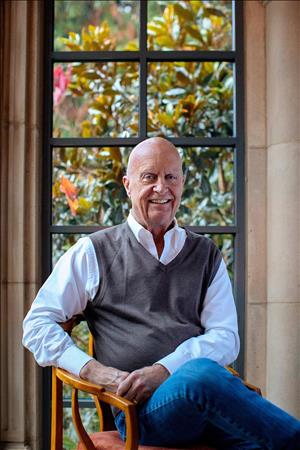

Allen Shoup (1943-2022) played a leading role in developing Washington’s wine industry as the longtime head of the state’s biggest winery, Chateau Ste. Michelle, and later as the owner of his own acclaimed winery, Walla Walla’s Long Shadows Vintners. Shoup came to Ste. Michelle in 1980 after working for Ernest and Julio Gallo in California. He immediately realized that in order for Chateau Ste. Michelle to thrive, the entire Washington wine industry needed to thrive. He worked with others to achieve the designation of Washington’s primary wine-growing region as the Columbia Valley American Viticultural Area (AVA) in 1984. He tirelessly promoted not just his own company’s products, but wines from his Washington competitors, because, as he later said, California was their real rival. He retired from Chateau Ste. Michelle in 2000 and launched his own high-end winery, Long Shadows Vintners, in 2002.

Formative Years

Allen Shoup was born on August 31, 1943, in Utica, Michigan, and was raised in Farmington Hills, a suburb of Detroit. He received a degree in business administration from the University of Michigan, and later earned a master’s degree in psychology from Eastern Michigan University. Wine played virtually no part in the Shoup family during his upbringing. "The closest thing I knew about wine was, I had gotten drunk one time on Mogen David," said Shoup, with a laugh (Kershner interview).

He was aiming at a career in business. He worked full-time for Chrysler in Detroit while finishing his master’s degree, and then was drafted into the Army during the height of the Vietnam War. He served two years, mostly in the Pentagon, where he was posted for his psychology background. He was involved in many projects, including psychological research on how to convince trained personnel to stay in Vietnam for longer than their one required tour of duty. "People who stayed had a much higher survival rate," Shoup said (Kershner interview). However, that was a hard sell during the depths of the war in 1968 and 1969. "It was just such a messy, sordid war," said Shoup. "I was very anti-war all the while I was there, but what could you do? A lot of people were – a lot of military people were" (Kershner interview).

When he got out of the Army in 1969, he went to work almost immediately for Amway, the direct-sale health, beauty, and home-care company based in Grand Rapids, Michigan. It was a good career move – Amway was growing. He became a product developer and developed a number of their personal-care products and fragrances.

Into the Wine Business

After about five years, a corporate head-hunter came calling from an unlikely place: Modesto, California, the headquarters of Ernest and Julio Gallo, the biggest winery in the world and the best-known wine label in the U.S. Gallo needed Shoup’s marketing talent and Shoup jumped at the chance. His title was group product manager, and he later became one of the company’s marketing directors.

The American wine industry was still small in 1975, but E&J Gallo was a behemoth. Half the wine sold in the U.S. was Gallo wine. Their big sellers were cheap mass-produced jugs of Hearty Burgundy, but they were starting to produce fine varietals for what was still a niche market. Shoup stayed with Gallo for about three years and learned not just about wine marketing, but about the mysterious allure of wine itself. "I always would say the reason that [wine] certainly isn't a fad is because, what fine wine does is unique," said Shoup. "It's like discovering art or opera or symphony or something. You don't give it up, because it's life changing. Fine wine has this unique ability to improve the food, and the food has the unique ability to improve the wine. And once people learn these connections, they don't go back and stop drinking wine" (Kershner interview).

The Gallo job changed the direction of Shoup’s life – but there were still a few more detours before he landed in Washington’s wine industry. First, he was lured away from Gallo by another California company, Max Factor, based in Hollywood, because of his Amway background with fragrances and cosmetics. Not long after, he was lured away from Hollywood by Boise Cascade to be director of corporate communications, a job that turned out to be less than a perfect fit.

Then, in 1980, Chateau Ste. Michelle came calling. Actually, this was the second time that Chateau Ste. Michelle had come calling. A year or two earlier, he had interviewed with the Woodinville winery while still at Max Factor, but the job offer was not what he wanted. The second time, however, the job was too good to turn down. The winery offered him the position of head of marketing and corporate development. He would also be on track for the top management job. Shoup jumped at the chance, eager to get back into the wine business – and to do it in a wine region that was small but loaded with potential. "When I started out, there were maybe less than a dozen wineries [in Washington] and all of them very tiny," he said. "The only big winery was the one I was hired to run" (Kershner interview).

Changing the Face of Ste. Michelle

Chateau Ste. Michelle had been sold to U.S. Tobacco Co. and had opened its big new chateau and tasting room in Woodinville in 1976. It was easily the most recognized name in Washington wine. It accounted for 80 percent of the Washington wine sold. Yet there were some obvious challenges. Most of the winery’s reputation and sales came from Johannisberg Riesling. "It was our main grape. [We were] the biggest producer of Riesling in the world," said Shoup (Kershner interview). Yet Riesling wasn’t particularly popular outside of the Northwest, and the rest of the country was unaware that Washington even had a wine industry.

Shoup had one large advantage: U.S. Tobacco was willing to invest millions to expand Chateau Ste. Michelle, and, in essence, to expand the entire Washington wine industry. "There are people who refer to me as the father of the modern day [Washington] wine industry," said Shoup in a 2022 interview. "I don't think that's the correct term. I think, I had a vision for what could happen, but the fact of the matter, the credit doesn't go to me, it goes to the parent company that gave me the resources to do what I did" (Kershner interview).

He later asked one of the board members why they were willing to invest so much money – close to $100 million by some estimates – in Washington’s wine industry. They could have spent the money on a proven region, such as Napa Valley. The board member said, in Shoup’s recollection, "Well, the way I see it, anybody who looks at what we did today, is going to think that we're crazy. But, 30 years from now, they're going to wonder how we had the insight to do it" (Kershner interview).

Shoup would later call that a "pretty profound" and "prophetic" statement. "I wasn't sure he was right when he told me that, but it turned out, he was," said Shoup (Kershner interview). In fact, Shoup himself had the same hopes. In 1981, he publicly made a number of predictions: That Washington’s wineries would increase five-fold; that the wine regions of Washington would become major tourist attractions, and that "within 10 or 15 years, the Pacific Northwest will be better known for red wines" than for white ("Wine Industry Gets Bouquet"). All three predictions would come true.

How did Shoup go about selling Chateau Ste. Michelle’s relatively unknown wines? Shoup’s Gallo experience proved to be invaluable. "Gallo understood the importance of a really well-trained, highly disciplined sales organization," said Shoup. "I knew that was going to be important. In the beginning, I put more money into public relations than I did sales because we couldn't sell something that nobody knew about" (Kershner interview). By this time, Shoup had developed a friendship with California wine legend Robert Mondavi, who had taught Shoup the importance of public relations and building an image.

Shoup’s marketing instincts were perhaps best displayed after he was given a tour of Chateau Ste. Michelle’s gigantic new production facility under construction in Paterson. This was right in the heart of the state’s vineyard region and the idea was to grow the winery’s output to an unprecedented 2 million cases. When Shoup saw the building, he noticed the big sign out front that read "Chateau Ste. Michelle River Ridge." Were the words "Chateau Ste. Michelle," necessary – or even a good idea at all? "I had to go in and say, 'Look, you want 2 million cases, but do you really care that it has to be under one label? I mean, it counts just as effectively if it’s under two labels, because if we have two labels, we can get two placements'" (Kershner interview).

By that, he meant two shelf placements in stores, and double the exposure. He convinced the other executives to give wines from that facility a new label. "We tore that sign down, and wrote ‘Columbia Crest,’” said Shoup (Kershner interview). Columbia Crest was to be designated mostly as a lower-cost label compared to Chateau Ste. Michelle, but it also produced its share of fine wines, including the red wines that Washington was becoming known for.

The strategy worked spectacularly well, and before long Columbia Crest became "the largest producer of Merlot wine in America" (Blecha). Columbia Crest also received many best-value awards from wine publications. This success also enhanced Shoup’s reputation, leading Washington wine writers Ronald and Glenda Holden to say he was "generally recognized as one of the industry’s most brilliant marketers" (Holden, "Gambles"). In 1987, the company was reorganized as Stimson Lane Wine & Spirits, Ltd., an umbrella organization that included Chateau Ste. Michelle, Columbia Crest, and the winery’s sparkling wine label, Domaine Ste. Michelle. Under Shoup’s leadership, other labels would be added, including Snoqualmie, Northstar, Villa Mt. Eden, and Conn Creek.

Promoted to the Top

By 1983, Chateau Ste. Michelle had become America’s second-largest premium wine producer. That year, Shoup was named the company’s president and CEO, titles he held for nearly two decades. One of his early initiatives was to gain an American Viticultural Area (AVA) designation for the Columbia Valley, which would enable the industry to move beyond the term Washington wine. This was an area that included nearly all of Central Washington’s wine-growing regions, including the Columbia, Yakima, and Walla Walla valleys, now filled with dozens of vineyards and wineries. Shoup hired Dr. Wade Wolfe and Dr. Walter Clore (1911-2003) to draft a petition for appellation status. The federal government granted the request in 1984. This was a boon not only to Chateau Ste. Michelle, but to many competing wineries.

"I always used our resources to help the rest of the industry because it was self-evident to me that if Ste. Michelle's going to be a major wine company, it's got to be in a major viticultural region, and viticultural region by definition means lots of successful wineries," said Shoup (Kershner interview).

By the 1990s, red wines were becoming increasingly important in Washington. Shoup credits that to two developments. First, the influential TV news show 60 Minutes aired a segment in 1991 called "The French Paradox," which touted red wine as part of a healthy Mediterranean diet, and a key to longevity. Shoup was watching that night, and immediately knew it was a turning point. "It was like an earthquake for the industry," he said. "All of the sudden my sales started booming" (Kershner interview). The second development was that Washington wine growers were proving, beyond doubt, that they could grow world-class red grapes, including Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and, increasingly, Syrah.

Still, the battle was to convince consumers around the country. When Shoup was approached by Clay Mackey (b. 1949), a fellow winemaker, to join and help fund a new entity called the Washington Wine Commission, he gladly joined. Cooperation within the state was vital. "I felt we weren’t competing with other wineries in Washington," he said. "We were competing against Mondavi and Beringer" (Kershner interview). He added another California competitor, Kendall-Jackson, to that list as well.

Shoup came up with creative ways to get the word out to the rest of the world about the quality of Washington’s wines. He invited wine writers from big media markets to luncheons in New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles, where they would get a chance to taste Washington wines. One such event, at the Oak Room in New York’s Plaza Hotel, paid especially large dividends, when it resulted in a two-page Time magazine story headlined, "Washington’s Bright New Wines" (Demarest).

In the 1990s, Shoup had achieved his goal of making Chateau Ste. Michelle, Columbia Crest, and Domaine Ste. Michelle a force in the national industry. Shoup remembered a time, in the early days of his tenure, when he would sit – mostly ignored – in the waiting room of his Chicago distributor, watching California wine competitor Barney Fetzer waltz in and get taken to lunch. "The same distributor, about five or six years later, would send a car to the airport to pick me up," said Shoup. "We became big enough that we were a very important player" (Kershner interview).

Collaborating on Col Solare and Eroica

Shoup had another ambition. He wanted to emulate Mondavi, the California wine pioneer, and create ultra-high-end wines in collaboration with legendary European wine names. Mondavi had successfully created a sought-after wine called Opus One, in collaboration with Baron Philippe De Rothschild of France. So Shoup initiated two Chateau Ste. Michelle collaboration projects. One was in partnership with the Antinori family from Italy, and it produced a super-Tuscan-style red wine called Col Solare. The other partnership was with Ernst Loosen, a German winemaker, and it produced a Riesling called Eroica. These winemakers used Washington grapes to create wines in their own famous styles.

Eroica turned out to be an unqualified success, with bottles retailing for $24 at a time when Chateau Ste. Michelle had never before sold a bottle of Riesling for more than $10. Col Solare was a smash success as a fine red wine, but from a sales standpoint, it never became a national hit on the level of Opus One.

This was not the only way in which Shoup emulated Robert Mondavi, whom he had met and befriended during California sojourns. "He really knew how to build an image for Mondavi," said Shoup. "... His belief was that wine was an extension of all the cultural arts ... Gourmet food, fine wine, fine music, fine theater. All on a continuum of appreciated arts that make life what it is" (Kershner interview). Following that lead, Shoup, an art connoisseur, found a way in 1996 to incorporate art directly onto Chateau Ste. Michelle’s Meritage wine bottles in the new Artist Series. The first labels in the series depicted glass forms from acclaimed Northwest glass artist Dale Chihuly (b. 1941), a friend of Shoup. Thereafter, whoever was selected to receive the Libensky Award, an honor Shoup established in collaboration with the Pilchuck Glass School, was chosen to design the label.

Settling a Labor Dispute

Challenges arose during Shoup’s tenure, including a contentious labor dispute with farmworkers who tended and picked the grapes for Chateau Ste. Michelle. The United Farmworkers of Washington State organized a boycott of Chateau Ste. Michelle wines in the late 1980s and early 1990s, citing low wages and the company’s failure to recognize the union. However, this was no typical management-versus-unions clash. Shoup had been a lifelong supporter of labor movements. When Shoup was asked about the union organizers who were pushing for recognition, he said, "Probably, if I had their job, that’s what I would do, too" (Williams).

Shoup, in fact, supported passage of a Washington law that would give farmworkers the power to demand collective bargaining from their employers. It was an apparent contradiction, but one that recognized that most of the company’s farmworkers were in favor of a union. "We know we should have an election," said Shoup. "We just want conditions that make it acceptable" (Murphey). The dispute came home for Shoup, literally, in 1992 when the union attempted to protest outside of Shoup’s home in his gated Shoreline community. "Allen Shoup, donde esta (where are you?)?" chanted the protesters (Wilson). Guards at the gate told them that Shoup was not home and the protesters disbanded after staging a symbolic union vote.

The state law never passed, but Chateau Ste. Michelle’s labor dispute was finally resolved in 1995 when the company and the union agreed to allow workers to vote to join the United Farmworkers. "Our hat’s off to president Allen Shoup for agreeing to this," said the union president (Buck).

Creating Long Shadows Vintners

Two fundamental changes came to Shoup’s life in 2000. First, he and his wife Kathleen bought a spectacular new house in The Highlands. It was just a few doors down from their former house, but this one came complete with circular driveway, fountain, and what The Seattle Times described as "a Sound of Music terrace" with gorgeous views of Puget Sound and the Olympics. The house is filled with a glass art collection including pieces from Chihuly and William Morris, paintings, and artifacts from their world travels. "I think everyone should spend some time nurturing their appreciation of aesthetics," said Shoup. "And a lot of my male friends find that tedious" (Teagarden).

The second big change: He announced his retirement from Chateau Ste. Michelle. U.S. Tobacco had lost a major antitrust lawsuit, which put a damper on any expansion projects. "My nature is, I’m a creator and a builder ... I’m not a good maintainer of things, and Ste. Michelle was going into a maintenance role," said Shoup (Kershner interview).

He also had another big project in mind – his own winery. The concept was similar to what he had done with Eroica and Col Solare. "I thought, I’m going to start by bringing in world-class winemakers, famous winemakers from around the world, and give them 25 percent equity in their particular brand" (Kershner interview). He assembled what he called his Dream Team of winemakers, including Randy Dunn from Napa Valley, Agustin Huneeus from Napa Valley, Michel Rolland from Bordeaux, Armin Diel from Germany, Phillipe Melka from France, Gilles Nicault from France, John Duval from Australia, and Ambrogio and Giovanni Folonari from Italy. Then he brought them in to produce best-of-type wines in their own style from Washington grapes, under seven different labels. Shoup picked the name Long Shadows Vintners as the umbrella entity because each of the winemakers have "cast long shadows on the industry" (Skeen).

Shoup announced the formation of Long Shadows Vintners in 2003 and began marketing its wines in 2004. By 2006, Long Shadows opened its elaborate production facility just outside of Walla Walla, decorated with glass art from Chihuly. In 2007, Food & Wine magazine named Long Shadows its Winery of the Year.

The original concept evolved over the years. While there are now [2022] nine labels under the Long Shadows umbrella, Gilles Nicault oversees the production of all labels. Some of the winemakers still take a hands-on role in producing their wines, while Nicault has "assumed winemaking duties" for others "in the style of their original winemakers" (Long Shadows website). In 2022, the Long Shadows tasting room in Walla Walla placed first in USA Today’s 10 Best Reader’s Choice Award, beating out tasting rooms in Sonoma and Napa. Long Shadows also has a tasting room in Woodinville – in Shoup’s former Chateau Ste. Michelle neighborhood.

Long Shadows Vintners has become a family affair, with Shoup’s stepson Dane Narbaitz as president, and son Ryan Shoup as director of retail sales. Shoup is proud of the success that he has had with Long Shadows, and with Chateau Ste. Michelle before that. Yet he singles out another achievement as his proudest. In 1988, Shoup helped create one of the most successful wine-related charity events in the U.S., the annual Auction of Washington Wines. He and several collaborators hoped it would generate from $100,000 to $200,000 per year. By 2020, it had "raised more than $50 million for Seattle Children’s Hospital and Washington State University’s wine program" (Degerman). In 2013, Shoup was named Honorary Vintner at the auction, one of the highest accolades in Washington’s wine industry. "Of all the lucky things I’ve been affiliated with in my lifetime, this is one I hold most significant," he said (Degerman and Perdue).

Legacy

Shoup earned a number of awards over his tenure, including Sunset magazine’s Western Wine Awards Lifetime Achievement Award, the Walter Clore Center’s Legends of Washington Wine Hall of Fame, the Junior Achievement/Puget Sound Business Journal’s Lifetime Hall of Fame award, and the American Wine Society’s Award of Merit, the society’s highest honor. And Sunset magazine’s wine editor did indeed say in 2011 that "Allen Shoup is considered by many to be the 'Father of Washington's Wine Industry'," ("Shoup to Receive Lifetime Achievement Award").

Looking back on his career shortly before his death in 2022, Shoup said he may have deserved some of the acclaim that was showered upon him. "Another person may not have made as many good decisions as I had," he said. "But it'd be naive for me to think that there weren't people out there who could have done better. I don't know if it sounds like false modesty or what, but I just always felt I was very lucky. I was lucky to be given the opportunity. I didn't deserve that luck. I didn't do anything to earn it. It just happened" (Kershner interview).

More: Jim Kershner's interview with Allen Shoup