While Snohomish County's journalistic history broadly mirrors patterns seen throughout the state, the county can claim one of the earliest territorial newspapers, six labor and socialist publications, three women publishers in the early 1900s, a 1911-1912 Black newspaper, several equally short-lived papers in Scandinavian languages, numerous small-town newspapers and an early Tulalip press. So prolific were publications prior to World War I that a researcher working in the 1980s to microfilm remaining issues commented: "There were so many newspapers, I didn't think there were enough people around to read them all" ("Extra, Extra ..."). Most likely, there weren't, and strong competition for advertising revenue and subscribers led to the demise of most papers, their editors moving on to new locations or new careers. But press equipment was not easy to relocate, so it was common for a failing newspaper to merge with another or to be resurrected under new ownership and name, leaving a tangled lineage. Journalists not only witnessed the changes happening in the region, they also helped to create that change, and left behind an invaluable resource for researchers. By the 1920s, journalism had become big business, with fewer publishers holding considerable power. Thanks to preservation efforts over the decades -- library archiving, microfilming, and digitizing -- many surviving issues are now available to researchers while others await funding and copyright clearance for digitization.

First Newspapers

While news of happenings in what became Snohomish County were occasionally mentioned in territorial papers, coverage coming directly from the county began in the town of Snohomish, platted in 1861 and incorporated in 1883. Located on the north bank of the Snohomish River, the town began to grow around a logging and lumbering economy. A small number of indigenous people continued to live there as well. Two prominent non-Native settlers were lawyer Eldridge Morse (1847-1914) and Dr. Albert C. Folsom (1827-1885), the latter opening a museum dedicated to the arts and sciences. A small and cultured group of men and women established a local Athenaeum Society and in 1874-1875 published a handwritten paper, The Shillalah, shared in small notebooks, which are now preserved at the University of Washington. Several writers contributed topics ranging from a list of businesses, new scientific discoveries, current local and world events, and newsy advice to local residents. One entry warned settlers not to be deceived by the region's warm winters, since the continual rain often brought severe illness, especially to children and the elderly. Although unsigned, most of the writing appears to have been done by Morse and Folsom.

The Shillalah was a precursor to the Northern Star, which began in 1876 with Morse as editor. Printed on a Washington Hand Press, the Star circulated to residents and beyond, serving as a human connection, a chance for businesses to publicize their goods and services, and a means of keeping settlers aware of world events. Folsom contributed a number of articles about new scientific findings. Remaining copies show the erudite nature of the Northern Star, which in part led to its end in 1879. Morse wrote that its circulation had dropped from 800 to 600 due to a depressed economy and that enemies wished its demise. Financially the paper was not breaking even.

Three years passed before a second newspaper appeared, the Snohomish Eye, which started in January 1882, and was managed by Carl Missimer and C. H. Packard. Starting as a small four-column, four-page weekly, printed on a steam-powered cylinder press, the Eye was successful enough that by 1891 -- a year of great county growth -- it ran as a tri-weekly, delivered by carriers at a cost of $5 a year. The paper ran until 1897. It was joined by rival papers the Snohomish Champion (1885-1886) and the Snohomish Weekly Sun (1888-1892). November 1889 saw the debut of the Marysville Leader (1889-1891) and the Edmonds Chronicle (1890-1892), the latter destroyed by fire, after which its publisher moved his plant to Snohomish to merge with the Snohomish Democrat (1892-1894).

Chronicling Two Decades

The decades of the 1890s and early 1900s have left us newspaper writing at its optimistic best as journalists documented the explosive changes and chaos they were witnessing. This period coincided with advancements in newspaper technology that speeded mass production, allowing newspapers to be consumed by a large audience. East Coast and Midwest newspapers had spurred the migration west, journalists writing about discoveries of gold and the availability of homestead land. Opportunities were there for journalists, as well, as they joined the movement west. Settlers came to Snohomish County for a number of reasons, some for the adventure, others for the rich farmland, and more for the region's vast timber resources -- lumbering and logging.

Development at Port Gardner Bay drew national attention because its backers were wealthy investors with big industrial plans. The Everett Land Company, backed in part by John D. Rockefeller, planned a city based around a nail works, a paper mill, a smelter, and a barge works. Lumber and shingle mills filled in along the city's shoreline. The paper mill, along the Snohomish River at Lowell, would provide a close source of paper for publications. The Everett News (1891-1898) was the first paper to arrive. Editor James W. Connella (1859-1939) set up his plant on the river side of town. Describing the scene at Everett, Connella wrote:

"At night the city seems to be on fire at its edges. The city at present is cleared in the center, and the blasting is carried on in a circle around the inhabited portion, as it were. After the work of the giant powder is over the torch is applied and when night comes on, Everett appears to be almost enveloped in flames. Some of the burning trees form very pretty sights. Immense trunks will be seen a red hot mass with flames pouring out from the top. In other cases the flames creep up tall trees and locate for a while on the very top, making a sort of torch. The blast and blaze are doing rapid work in the clearing of Everett lands" (Everett News, December 17, 1891).

Within weeks the Everett Times (1891-1895), Everett Herald (1891-1895), and Everett Tribune began rival papers, daily documenting the construction of buildings, homes, and stores. Reporters wrote of the scarce lodging available for those who came to buy land and found it necessary to camp out in tents or sleep aboard steamboats at night. One story that has lasted over the years is about the town's first undertaker, having no customers yet, allowing men to sleep in his coffins at night. The Times published stories written by school children describing what they saw as Everett was being built.

Snohomish city residents felt challenged by the Everett development, but their population was also increasing, and new publications began: the Snohomish Weekly Sun (1888-1892), the Snohomish Advance, and the Snohomish Tribune.

North of Everett, Stanwood and the Stillaguamish Valley drew farmers and dairy families, as well as loggers and newspaper founders. Stanwood newcomers seemed particularly caught up in the excitement of the Klondike Gold Rush. The Stanwood area supported multiple papers: the Stillaguamish Times (1889 to 1890?), Stanwood Post (1890-1895), Stanwood Press (1897-1900), Stillaguamish Valley News (1890), and Stanwood Tidings (1903-1917). Four small-town newspapers -- the Arlington Times, the Marysville Globe, the Snohomish County Tribune, and the Monroe Monitor -- began in the 1890s.

A development at Brackett's Landing grew into the town of Edmonds, where newspapers included the Edmonds Chronicle (1890-1892). Other 1890s county papers included the Silverton Miner (1893-1894) and Monte Cristo Mountaineer (1893-?). All suffered hardship in the 1893 Silver Panic and the five-year depression that followed. For those publishing in remote areas of the county, relocating was difficult. William Whitfield in his 1926 history of Snohomish County wrote that after one year of publishing, the editor of the Cascade Miner at Galena "... printed a brief but sarcastic valedictory, packed up his printing outfit and wended his way back over the mountain trail." In 1897 Snohomish lost its position as county seat to Everett, the bitter fight and supposed stolen election fully covered in the press.

A New Century

A second huge wave of economic development came in 1900 when, with a good national economy, Everett's Rockefeller interests were transferred to the Everett Improvement Company under the management of James J. Hill. New industries were built along Everett's shorelines, each industrial addition making the news. By 1910 the city and county had tripled in population with many men and women employed in the mills, where work hours were long, conditions dangerous, and business conducted by powerful bosses operating in boom-and-bust cycles. With these conditions, it is not surprising that Everett became a strong union town by the late 1890s.

A large number of Scandinavian immigrants had arrived at this time, many bringing with them their democratic socialist ideals, making Everett fertile ground for labor and socialist newspapers. Helping new arrivals assimilate, several Scandinavian/English newspapers began with short runs.

From its start, the Everett News served as the official newspaper of the local union movement until its demise in 1898. A new voice emerged circa 1903, the Labor Journal, based in Everett. Its first issues listed dozens of unions, with new ones forming, the rise of the Union Label advertisers, and the activities of the Women's Label League. The Labor Journal covered news about the shingle weavers' strike that led up to the November 5, 1916, Everett Massacre. Its editorials clearly showed support for trades union workers versus that of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). As repression became greater against IWW speakers in Everett, Labor Journal editor Ernest Marsh (1877-1963) wrote passionately condemning the brutal beatings by vigilante mill men against IWW street speakers in Everett shortly preceding the Massacre.

The Labor Journal strongly supported women's issues, including the 1910 suffrage movement and the 1912 passage of Washington's 8-Hour Work bill for women, which was authored by Labor Journal's business manager and State Senator John Campbell (1890-1924). Everett's Labor Journal continued until 1976, a good deal of that time focusing on state and national labor news.

Everett's union strength made it a central location for Washington State Socialists, and from 1911-1919 five socialist newspapers were published in the city. The first was the Commonwealth (1911-1914), which soon had financial troubles, its assets seized by debt collectors. Remaining supporters began a new publication, the Washington Socialist (1914-1915), which became the Northwest Worker (1915-1917), followed by the Co-operative News (1917-1918), and finally the Party Builder (1916-1919). The Co-operative News continued into mid-1918 and its last issues told of its coming closure, based on government suppression of socialist and radical publications taking place throughout the nation following the federal Espionage Act of 1917, amended in 1918.

The Labor Press Project at the University of Washington gives a thorough history of these publications, which can be found online. Surviving copies have been microfilmed on one reel and are available in libraries. Labor Journal issues from 1909 to 1976 are available as a Library of Congress Online Resource.

Women publishers

Three women in Snohomish County served as early newspaper publishers. A widowed mother, Missouri T. B. Hanna (1857-1926), came west from Minnesota in 1904 and settled in the mill town of Edmonds. Purchasing the weekly Edmonds Review the following year, Hanna ran it for five years and is acknowledged as the first woman newspaper publisher in the state. Hanna helped to start the Snohomish County Press Association in 1906. She sold the Review to her rival publication the Edmonds Tribune in 1910, and the papers merged to become the Edmonds Tribune-Review. Hanna then turned to supporting women's suffrage, publishing Votes for Women, which served as the official monthly newspaper of the state's suffrage movement. The paper carried news from suffrage groups across the state as well as biographies of influential suffragists. With an eye-catching format, the publication often carried a political cartoon on its front page. The paper was published in Seattle and sold for $1.50 annually or 10 cents a copy.

After successful passage of the state Suffrage Act in 1910, Hanna renamed the paper The New Citizen. It ran for two years, covering women's issues and politics and supporting political candidates who focused on women's issues. Copies of both monthly publications survived and have been digitized and placed online in the University of Washington's Special Digital Collections.

Socialist writer and speaker Anna Maley (1872-1918) arrived in Everett to edit The Commonwealth and used the position to launch her campaign for Washington governor in 1912. She received 12 percent of the vote. Internal squabbles among state Socialists led to her leaving the region. Maley continued speaking, writing, and traveling across the U.S.

Iowa-born Alice White Reardon (1867-1951) moved with her husband to Monroe in 1913 and, following in the footsteps of her journalist father, brother, and husband John Reardon, purchased the Monroe Independent in 1913 and began covering small-town news. A decade later, she also purchased the rival Monroe Monitor, merging the two publications under the name of the latter. She primarily managed the business side of the publication, staying with the paper until she sold it in 1943.

The Rising Sun and Tulalip Bulletin

Following a military career in a U.S. Buffalo Soldier regiment, Thomas L. Cate moved to Everett in 1911 with the dream of starting a Black farming colony. He began publishing a newspaper titled The Rising Sun: Dedicated to the Interest of the Negro Race, the paper lasting for two years. Only one issue, January 20, 1911, has survived. It has been preserved and shared in the University of Washington's Special Collections. The 1911 Polk's city directory lists Cate as working in general real estate and as the Rev. Thomas L. Cate, Pastor of the Bailey Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church. Cate's dream was to bring Blacks from the East to begin a farming community on 800 acres of land near Sultan. Newspaper stories show that he was opposed by members of the Fern Bluff Grange and his plan did not come to fruition. Cate and his wife Rosa stayed on in Everett, Cate dying young but Rosa living to 95. She was buried in Everett's Evergreen Cemetery.

While the Marysville Globe occasionally covered news about the Tulalips, a newspaper called the Tulalip Bulletin was issued from the reservation from September 1916 to April 1919, published by the superintendent of the Indian boarding school, Charles M. Buchanan (1868-1920). Much of the news at this time was about World War I and Tulalip men who served. When the Tulalip Bulletin ended, there would not be another newspaper published at Tulalip until 1966. Only one copy remains of the Bulletin, and it has been digitized by University of Washington Special Collections

Small-Town Newspapers

The town of Granite Falls serves as the gateway to the Mountain Loop Highway, Mount Pilchuck, Big 4, and Monte Cristo. Its newspaper history dates from 1903, the year of town incorporation, and continues through the 1960s. The Granite Falls Historical Society has preserved and made digitally accessible on their website papers including holdings of the Granite Falls Record, Granite Falls Press, and Snohomish County Forum (serving Granite Falls and Lake Stevens). Reporters covered local events, mayor and council races, and stories of local residents, plus legal listings and ads. The Index Miner and Index News would publish for short runs in the early 1900s.

After World War I

In 1920 the U.S. Census counted an Everett population of 27,644, and the decade proved to be a prosperous one. The lumber and shingle industry dominated the city's economy, with fishing and boatbuilding adding substantially to city and county wealth. Newspapers were now big business, and the Everett Daily Herald and Everett Morning Tribune rivaled each other with daily coverage.

With improved quality of photo engravings and new presses that could double printing capacity inexpensively, most Everett residents depended on print news and ads. Granite Falls, Marysville, Monroe, Edmonds, Arlington, and Stanwood continued their local coverage. Advertising expanded the papers' size with elaborate graphics designed to sell clothes, yard goods, autos, movies, home remedies, services, and more, the larger papers now expanding issues with separate sections for sports, politics, local and world news, and entertainment. Photographers joined their staffs.

Newspapers had one big challenger, radio. In Snohomish County there was Everett's KFBL/KRKO, which declared itself "The Voice of Puget Sound." But rather than dealing a death blow to print journalism, the competition spurred publishers to provide more attention-drawing layouts to increase sales at newsstands. They also began carrying radio program schedules, generally printed alongside a growing number of movie theater ads. Meanwhile, sports pages of the 1920s had plenty of football to cover with the success of Enoch Bagshaw (1884-1930) and his Everett High School championship teams.

The Great Depression

Evidence of the hard times during the Depression can be seen first-hand when looking at original papers from this time period. They are yellowed and brittle in comparison even to older newspaper copies, attesting to the necessary cost cutting and use of cheaper paper, with a high sulfite content. Papers also cut staff. Still, subscribers counted on newspapers to keep them informed about mill closures and openings, and perhaps even more, needed the continual optimism of the press, hoping for the return of good times.

Keeping this optimism alive, journalists daily reported on government work projects in Snohomish County and readers followed news about the building of Legion Park, the transformation of Forest Park, road and parks development throughout the county, construction of the Everett Public Library, the Everett Civic Auditorium, and a county airport that eventually became Paine Field. On the arts and culture scene, Everett's Nancy Coleman (1912-2000) was beginning her career on stage and in the movies and received good local press coverage. Her father, Charles Sumner Coleman (1881-1932), served as managing editor of the Everett Daily Herald, and her mother, Grace Sharpless Coleman, (1885-1977) was its society reporter.

A Tale of Two Papers

The evolution of two Everett newspapers is instructive. The Everett Daily Herald began on January 5, 1901 as the Daily Independent, with publisher Sam A. Perkins, and is not the same Everett Herald that died in the Panic of 1893. James B. Best (1864-1922) purchased the paper in 1905 and either he or Perkins renamed it the Everett Daily Herald. The Best family continued as the Herald's publishers for 75 years, establishing a satellite news bureau for south Snohomish County in 1954, which became the Western Sun edition in 1970. The Bests sold to the Washington Post in 1973.

Surviving the depression years, the Everett Daily Herald dominated the newspaper scene in Snohomish County, its reporting focusing mostly on world news, U.S. involvement in World War II, and local wartime production at Boeing plants and the Everett Shipbuilding and Drydock Company on the waterfront. Articles followed changes at the Snohomish airport as it became a military base.

The Everett Morning Tribune/News Tribune grew from the 1891 Everett Times in the fall of 1891 and continued publishing under that name until June 1905, when it became the Everett Daily Record, operating until October of that year. Only a few random copies from this time period were saved. By November 1905 The Daily Record was called the Everett Morning Tribune. It continued under that name into the 1930s.

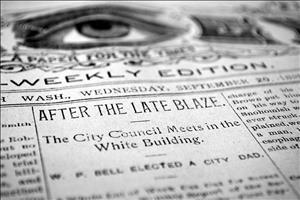

Everett Herald fire

On the evening of February 13, 1956, a three-alarm fire caused by a backfiring furnace igniting a pan of oil raged through the Everett Herald building on Colby and Wall Streets and blazed through its roof. Three firemen were injured but six Herald staff escaped. Newspaper files and the press photo collection were undamaged. The paper, owned by Robert Best (d. 1976), published again the following day using facilities of The Seattle Times and Local 23 Photo Engravers Union. This building is currently (2022) being prepared for use as the Everett Museum of History.

Accessing Early Snohomish County Papers

The value of historic newspapers to those researching the past can hardly be overstated, not to mention that old newspapers are fun to read. Libraries have a long history of saving original copies of local newspapers. In partnership with local heritage societies, the Washington State Library, the University of Washington, and the Washington State Newspaper Project, historic newspapers have been made publicly available, first on microfilm and then shared digitally online. Most newspapers, however, have been lost to time, with their names only traceable through legal records and city directories.

When looking for early Snohomish County newspapers, Everett Public Library and some libraries in the Sno Isle Library system are repositories and have copies on microfilm (including the Everett Herald, Everett Tribune, Marysville Globe, and Monroe Monitor). The League of Snohomish County Heritage Organizations and its individual historical societies are good places to check as well. The Stanwood Area Historical Society website, for instance, has a thorough listing of all known papers from the Stanwood and Stillaguamish Valley area, telling of their availability.

Snohomish County heritage groups, including Granite Falls and Monroe, have used Small Town Newspapers LLC to digitize some of their newspaper holdings, paid for through the Snohomish County Heritage Funds program. Granite Falls papers can be read at the organization's website. The Marysville Globe has digitized copies from 1892-1915, their project presently on hold for copyright restrictions. Issues of Everett's earliest newspapers as well as the Everett Morning Tribune and the Everett Herald are available on microfilm. Surviving issues of Everett's labor newspapers are available through Washington's Digital Newspapers, and extensive histories of each publication can be found in the University of Washington's Labor Press Project online. The Labor Journal, 1909 to 1976, is a Library of Congress Online Resource.